Читать книгу Hawks Rest - Gary Ferguson - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

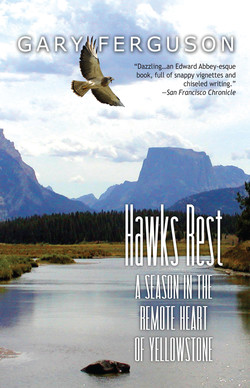

IT’S HARD TO BELIEVE AN entire decade has drifted down the river since I laced up my hiking boots on the porch of my home in Red Lodge, Montana, shouldered a backpack, and set out on a 140-mile hike to spend a season in the most remote place in the lower forty-eight states. A place that had only recently been identified by geographers at the National Geographic Society and Harvard University. Using precise satellite imaging, these few square meters were recognized as that one special place in America farthest away from a road. As it turned out, that place was in the extreme southeast corner of Yellowstone National Park, just a couple miles above the park’s border with the Bridger-Teton Wilderness. From there it was twenty-seven miles to U.S. Highway 26, where it crosses the wind-scoured, pine-covered Togwotee Pass. And in between was all the whoop and wild holler that any lover of wilderness could ever hope for. The thought of living for a time in that unfettered slice of the world was more than I could resist.

I’m happy to report that today this is still the wild heart not just of Yellowstone, but of continental America. Indeed, the greater Yellowstone ecosystem, of which the Hawks Rest country is center stage, remains widely recognized as the largest generally intact ecosystem in the temperate world. Grizzlies still roam the banks of Bridger Lake. In summer months, elk drift across the Trident Plateau, while golden eagles and red-tailed hawks trace circles in the sky above the Thorofare, watching for the twitch of mice and voles. In any given week in July or August lightning licks at the shadows of the lodgepole and Douglas-fir forests at the feet of the Absarokas, now and then starting fires that burn for days, even weeks, until finally extinguished by cold rain.

Meanwhile, wolves—including those from the spirited, but largely mysterious Delta pack, near Hawks Rest—still trot through the meadows along the Yellowstone, sending howls ringing through the ravines along Cliff and Escarpment creeks. Despite predictions by some of the people you’ll meet in this book, convinced that wolves would overtake the entire ecosystem, nothing even remotely like this has happened. In fact, the number of wolves in the park today is less than half the number living in the park when I first made this journey.

As has been true since the beginning of the wolf reintroduction in 1995, wolves continue to mark a divide between the healthy earth we wish for, and too many of our deepest fears. Several years ago, along the northern border of Yellowstone, the park became the stage for the unfortunate reality of wolves being taken off the endangered species list. As wolf management was handed over to the states, wolf hunting was endorsed without regard to pack locations. Many of the animals that were spending nearly all their days in the national park, wandering across the boundary only briefly, ended up being shot and killed. Most would die wearing the same curious looks on their faces they wore when considering humans who came merely to watch and admire them. Especially hard hit were alpha males and females, easy to spot, given they were often the only wolves wearing collars. From 2012 to 2013 alone the wolf population in Yellowstone dropped twenty-five percent, due in large part to reckless hunting policies.

For all the extreme attributions to wolves made by outfitters I met at Hawks Rest—that wolves were “super killers,” that they were creatures that routinely “kill for fun”—the average lifespan of a Yellowstone wolf is only about five years. While this is partly because of territorial disputes and occasional waves of disease, it’s also because bringing down elk or bison is so challenging that a lot of wolves end up dying in the attempt. In fact, Yellowstone wolf packs manage to take a prey animal in only one out of five attempts.

When wolves were brought home to Yellowstone, the vast majority of Americans were enthusiastic. And yet even a conservation project as popular as this, chronicled by literally thousands of media outlets around the world, would within a few years be dropped from public attention. Must we wait for a time when wild ecosystems like this one are even more rare, to reignite enough steadfast support to finally say no to those who would binge-slaughter America’s wildlife?

While wolves are without question a factor in reducing elk herds on the northern range—resulting in a much healthier population—a bigger influence still on elk numbers has been climate change. Warmer, dryer conditions in the past fifteen years have resulted in poorer grazing due to reduced nutritional values in native grasses. In turn, this has led to lower birth weights in calves. And that means lower survival rates.

But elk are hardly the only ones challenged by climate change. On the high, windy ridges along the northern and eastern borders of the park, huddles of whitebark pine are dying. They are disappearing due to infestations of pine bark beetles, an insect now able to thrive at high elevations thanks to warming temperatures. Some researchers believe the trees will be nearly gone in twenty to thirty years.

The Clark’s nutcrackers of the region have used whitebark for centuries, each bird burying as many as twenty thousand seeds in shallow caches to feed on through the winter. What’s more, the tree’s nuts are among the most important foods for grizzly bears; during years of abundant seed crops, a bear may get fully half her calories from them. Even more troubling is that this particular grizzly meal is disappearing at exactly the same time another one—spawning cutthroat trout—is dwindling too, the result of the region’s streams drying in the pall of drought.

Still and all, given the generally intact condition of this region, Yellowstone will be an essential wilderness baseline for scientists working to understand how to mitigate the effects of climate change. Hopefully our willingness to fund such studies and to implement the knowledge gained from them will be fed by a Yellowstone-style passion that extends finally to the planet as a whole.

The deep and abiding sense of place to be found in Yellowstone anchors us as a country even as it grounds us as individuals. Less than two years after I made my long and lovely trek to Hawks Rest, I encountered what would prove the biggest challenge of my life. My wife and wilderness companion, Jane, died in a tragic canoeing accident on the Kopka River of northern Ontario. Curiously, just days before, she had turned to me and—in a conversation we hadn’t had for a good dozen years—asked if I remembered how, if something ever happened to her, she wanted her ashes scattered in her five favorite wilderness areas. Of course, I said, and I ticked them off to her: the Sawtooth Mountains of central Idaho, that paradise of slick rock in Utah’s Capitol Reef National Park, the Wood River Valley of northwest Wyoming, the granite heart of the Beartooth Range, Yellowstone’s Lamar Valley.

Though I didn’t know it at the time, in that request she gave me a gift. The gift of taking my grief to the wilderness. Steeped time and again in the beauty and mystery of those wild slices of rock and water and sky, I found my way through the dark fog of hopelessness, and learned to live again. These days when I think of places like Hawks Rest, I know them not just for the power of the life that thrives there, but for the spirit that can rise from the ashes of the broken-hearted. Way out there, in the most remote place left in continental America, is a great deal of that which helps us sustain our sense of place. That which nourishes the essence of our humanity.