Читать книгу Hawks Rest - Gary Ferguson - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter One

POET JANE HIRSHFIELD ONCE REMARKED that when it came to personal callings, hers was best described as a struggle to match her life to a suitable landscape. Just my luck, I guess, that my own hankerings would lead me to a slice of high country roosting on a latitude halfway to the North Pole. In a town where kids hunt Easter eggs in drifts of snow, where girls head off to senior prom bedecked in strapless dresses and Sorrel boots. Yet what summer in these mountains lacks in duration it makes up for in heart, as bright and full of twitch as a young boy’s dreams. Evidence of what over a century ago author Helen Hunt Jackson—also writing about summer in the Rockies—described as “the great and tender law of compensation.” For ten glorious weeks, eleven in a good year, the days are wrapped in the kind of warmth that pops leaves and melts snow, that by some fine and murky sleight of hand manages to soften time itself. In the way a suburbanite might set his clock to the neighbor who steps out in his fuzzy slippers each day to retrieve the morning paper, June through August spins on a wheel of blooms and berries, fur and feathers. Rising in the dawn are clatters of geese and the trill of dippers, and with twilight the woozy swoop of nighthawks. In early June whitetail fawns are napping among wild roses at the edges of the cottonwoods, while clusters of moose are beginning their summer rounds of the neighborhoods—enthralling some of the neighbors, scaring others half to death.

As the curtain goes up on all this drama I do my best to stay put—park myself behind the house in a tiny meadow of clover and dandelion and timothy, peel off my shoes and plant my toes in the dirt like so many onions. But it never lasts. Around mid-June my mind begins slipping away, drifting from the breakfast table out the door and across the aspen woods, climbing through the lodgepole and Douglas-fir hanging from the face of Mount Maurice, Town Mountain, the lip of Silver Run Plateau. One minute I’m eating toast, and the next I’m daydreaming at ten thousand feet, adrift on any of several sprawling plates of tundra that flow out of the heart of the Beartooths like the fingers of a hand, high and cold enough to coddle the shards of winter until long after the Fourth of July. And so it goes, day after day, until there’s nothing left to do but make for the mountains.

This is no stray burp of granite rising out of the beet fields of northern Wyoming, only to sputter out on the banks of the Yellowstone. The Beartooths are only the beginning, the first chapter in a nine-million-acre epic known as greater Yellowstone, stretching from Livingston, Montana, south past Jackson, Wyoming, Absarokee to Afton. A place that, with the return of the wolf, is in possession of its full plate of historic species, forming what biologists often call the largest intact ecosystem in the temperate world. A land of avalanches and rockslides, windstorms and wildfires and ice.

These lands, in turn, are locked to other places of intrigue: uplands dropping onto quiet runs of winter range—those, in turn, tumbling onto sage-covered plains. In truth it’s the whole of it, including places way beyond what’s needed merely to cradle the comings and goings of bison and pronghorn and wolves, that has for so long informed our dreams of the intermountain West. Humbling, crushing expanses of terrain. The kind of unfettered spans that led many nineteenth-century writers to say there was just too much of it. Even today, longtime residents fashion their mental charts of the country not so much from towns or highways, but from scattered notions of peaks and rivers and canyons, from massive promontories blasted by the wind. Our sense of place is not driven as much by specific historical events as by the shiver of a vague but powerful story line—the unwavering notion that life west of the hundredth meridian is danced by land without end.

Over the years a few doodling geographers got it into their heads to chart the most remote places left in the continental United States. To no one’s surprise the lists have been full of places in the West. The Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness in Idaho. A lonesome toss of desert in southern Nevada. But the most remote spot of all is said to be right here in the northern Rockies, in the extreme southeast corner of Yellowstone National Park, in a place called the Thorofare. But with this news comes a catch, a jolt. Out of the million square miles of basin, range, peaks, and prairies that compose the interior West, the farthest it’s possible to be from a road is a trifling twenty-eight miles. One very long day’s walk. It’s not that we’ve lost our wild places. Rather that they no longer spill into unbroken quarters. Preserves that had been at the heart of vast, unfettered sprawls of land are for the most part now turning into islands. The rambling canvases of the West—places that were long the favorites for plastering our wildest, most eclectic dreams—have shrunk to something more comprehendible. If Freud was right to say that runs of unkempt nature serve the culture not unlike fantasy serves individuals, then our imaginations have surely become more tightly reined—walking, where once they ran.

When land preservation took wing in the last half of the nineteenth century, movements such as the effort to create Yellowstone National Park were thought to be fiercely patriotic. Congress itself got into the act in myriad ways, including securing as its first landscape painting for the U.S. Capitol a magnificent oil of the Yellowstone Rockies by Thomas Moran, bought for the astonishing sum of $10,000—a move fueled by the notion that such art was nothing less than a wellspring of nationalism.

“The wilderness soon made obsolete and alien the old ideas of rank, caste, and inherited aristocracy,” writes conservationist Peggy Wayburn. “Common man could be uncommon man.” It was the great sprawl of wild nature that launched a raft of fantasies about our being a chosen people. Nature that served as a resting place beyond the excesses of industry. Nature that provided the first blush of tradition in a culture suspicious of old ways.

My own particular itch to leave the timothy and the dandelions—to walk 140 miles from my front door in south-central Montana to that most remote spot in the country, to catch the early tide of summer in that area and ride it all the way to fall—was never about paying respects to lost paradise. Make no mistake about it, the Thorofare, like a precious handful of other locations in the West, is extraordinarily wild, a place of bugs and blowdown and bears, a landscape with strange and uncertain siren songs. All but the excessively outfitted will sooner or later sweat or freeze or be blown batty here, will lie out in sleeping bags and listen to branches snapping outside the tent and find themselves nearly too unsettled by thoughts of grizzlies to wander out and dump their bladders. In an age when nature gets offered up mostly in magazines and on television shows—like slices of pie, like a morphine drip—this is a place too sprawling to fit on the page, too unkempt for the calendar on the refrigerator door, too vast even for big screen digital high definition TV.

Yet given the fraying edges of the ecosystem, given a growing number of species unable to sustain themselves outside the wild core of Yellowstone—living in what biologists often refer to as a mortality sink—the time seemed right for a closer look. My intention was not only to get a sense of how some of the creatures in the Thorofare are doing, but also to gain a glimpse of the future. To gauge what the coming years might hold based in part on the impact such places still have on people’s lives. Greater Yellowstone, after all, is arguably the best we can muster, no longer intact merely by default, but design. No region in the country is under more scrutiny than this one, none more thoroughly researched and fought over and speculated about. To the degree America can yet muster stewardship for unfettered places, its commitment will likely never be greater anywhere than what it is here, in this so-called middle of nowhere, between the Tetons and the Beartooths, the Absarokas and the Centennials. To the degree we can preserve the dynamic processes of greater Yellowstone, there will be hope for other places. To the extent those processes fall apart, so will go others, many with hardly a whisper.

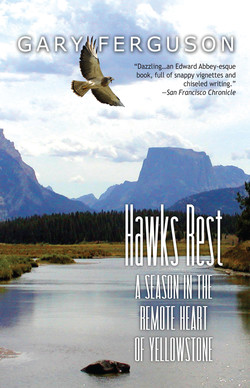

And so it happened that, on a warm day in June, my friend LaVoy Tolbert and I walked through the front door of my house and headed two miles up the highway to a trail at the foot of Mount Maurice, gritted our teeth and climbed four thousand feet onto one of those high, sprawling plateaus of the Beartooths, heading west. Our destination was an old guard station perched above the Yellowstone River called Hawks Rest, just two miles south of that most remote spot in the lower forty-eight. Rustic as a pack rat’s nest, beautiful as a quag full of camas lilies. We would be cabin tenders, the Forest Service told us, responsible for fixing up the building, mending fences, meeting the public. We’d keep a journal of the comings and goings of various wildlife for park biologists, mark illegal salting sites for the interagency grizzly team. The kind of job a person dreams of long before he gets there, misses long before he leaves.

The day is brilliant, the sun pouring down at ten thousand feet with that sharp blue tinge of summer in the high country. After what seemed like endless drought, the May snows were back again this year, prompting a grand show of wildflowers, the seeds of many having lain dormant for years. Every footstep falls beside alpine forget-me-nots and the pink, elfin blooms of moss campion. There’s the lemon of cinquefoil as well as great splatters of blue from penstemon and bluebell. Wet meadows show themselves from miles away, revealed by the unmistakable creams and ivories of globeflower and marsh marigold. And underlying it all is a mat of grasses and forbs as green as Ireland, reaching from the toes of our boots into what for those on foot is quite literally the middle of tomorrow.

This high up, the growing season shines for a couple of months and then fizzles like a cheap sparkler. Such brevity with fierce, shredding winds has resulted in a gathering of plants that never manage to grow much beyond ankle height. A land of crouching gardens. Winter snows pile to depths of twenty, thirty feet, sometimes at a rate of six feet in a single storm. Winds can reach a hundred miles an hour and, on any given day in late December or January, exposed skin will freeze in a matter of seconds. Spring doesn’t even think of showing up in these parts until late May and, even then, no sooner does she stick a toe in the room before the door gets slammed on her foot—over and over, until the sheer weight of her finally wears winter away, turns ice to water, snow to rain. And then at last June, when slabs of granite loosened by the freeze-thaw cycle begin falling in great crashes along the upper shoulders of the distant peaks. A kind of starting gun, if you will, signaling the beginning of a race to bloom before ice reappears just ten weeks later.

Grasses and sedges are scattered everywhere, in part because they remain nearly unscathed by the relentless pawing of the winds, while much of the rest of what grows here are cushion plants, mat-like vegetation composed of folded, ground-hugging leaves that not only avoid the wind but also trap heat. On any given summer day temperatures inside the leaves of a cushion plant may be twenty degrees warmer than the surrounding air. Those same folds have another benefit too: they catch tiny pieces of leaves and other debris that might blow by, thereby slowly raising the thickness of the underlying soil, maybe an inch or so every thousand years. The vast majority of these plants are perennials. Winter buds are held low, tucked right at or just below the surface of the soil; more than a few are wrapped in dark-colored hairs that trap heat and warm the emerging flowers. Others wear a kind of peach fuzz—a coating that not only limits the amount of moisture lost to evaporation, but also serves as a kind of solar shield, throttling down the ultraviolet in a place that gets twenty-five percent more light and twice the radiation of sea level.

Trekking across this, the largest contiguous stretch of tundra in America, offers hikers a kind of suspended rapture. Dizzy vistas tumble off in every direction. Underfoot are lilting plateaus, their treads and hummocks rising like ocean waves as far as the eye can see. To the west behind Hellroaring Plateau are the distant peaks of the central Beartooths, while in the other direction, some five thousand feet below, the Clarks Fork of the Yellowstone River flashes in the sun. Fifty miles to the northeast, along the southern reaches of the Crow Indian Reservation, the Pryors bristle with mature stands of Douglas-fir. And then the Crazy and the Snowy ranges, the Bull Mountains, and the Bighorns, the latter surrounded by a long grassy spill of the Great Plains. Crossing such country is a waltz best measured by the hour, by the footstep, by the inch.

This sense of being suspended, of swimming outside the normal passing of hours, is underscored by the slow, patient tick of alpine life. Along the crests of certain high, exposed ridges to the northwest lie clusters of nearly prostrate trees—commonly referred to as krummholz, or elfin timber—some having sprouted roughly around the time Pilgrims stepped off the boat at Provincetown; after four hundred years, the trees are no thicker than the business end of a baseball bat. The buttercups growing at our feet manage to produce only a single cell during their entire first year of growth. This lone cell then divides the following growing season, forms a bud in the third, and finally, after four years, unfurls a bright yellow bloom the size of a thumbtack. Even the larval stages of insects, which at lower altitudes last for roughly a month, may extend here for years.

When I first began imagining this long ramble across the tundra, I figured on making the journey alone. Despite the pleasures of companions, after all, even the best of company will keep you at arm’s length from loneliness, apprehension, and all the other wrinkled upshots of being neck deep in the wild—struggles that on days both good and bad can pry open all manner of ducky insights. But one afternoon at a conference in West Virginia, in a move that surprised even me, I blurted out an invitation to sixty-eight-year-old LaVoy Tolbert, the former education director at one of the nation’s best wilderness therapy schools for troubled teens. I’d first met him in that role during the late 1990s, showing up one day on his doorstep to write about the program; let’s just say he wasn’t happy to see me. The look on his face was in fact something you might see the father of the bride wearing on having spotted the town drunk at his daughter’s wedding. Some would call him unreasonable, ornery. But LaVoy Tolbert is a curmudgeon only to those he thinks might compromise those things most important to him, which at the time included the careful, patient mending of those dispirited kids. And I could hardly help but like a guy like that.

If anyone knows about using nature as a tool for drawing out those aforementioned ducky insights, LaVoy knows it. He talks often about how people had long gone to the wilds to figure things out, make adjustments.

Beyond the mere challenge of being out in such places, he often says, it was a matter of credentials. “Out in nature you’ve got 4.6 billion years of success—the best of everything, the finest the world has come up with, all around you, night and day. Go out for a stroll in the woods and you walk among champions.” Kind of like the farmer, he once told me, who each week takes his old plow horse to the racetrack to run against the Thoroughbreds. One day a friend stops him, asks why he keeps paying entrance fees to run races he can never win. “You’re right about that,” says the farmer, rubbing his chin. “That old horse ain’t got a chance. But then he sure does like the company.”

You might say LaVoy and I are ripe for that kind of company. Our lives are being torn open by new seasons—mine by a crossing into the heart of middle age, his by what he senses as the beginning of physical decline. Not that we don’t still turn stupid at the mere thought of the high country, using a day in the mountains as a kind of corkscrew to untap all the piss and vinegar still running in our veins. But these days we’re prone to squeezing other things from nature. Older lessons, deeper comforts. All morning I’ve been reaching back, thinking about how I ended up in such a place to begin with, fifteen hundred miles from where I spent my turn as a kid—buttoned to a big yellow swipe of northern Indiana, neck deep in the corn and the rust. With the lone exception of the St. Joseph River, which passed five blocks from my house on a sluggish meander from one end of town to the other—thus inspiring the whimsical name of our fair city, South Bend—it was land straight and tight as a bed sheet, the turnpikes and rail lines and county roads laid out true to the cardinal points of a compass. We spent our lives on the level, as some Hoosiers put it, a condition that almost certainly had something to do with one of the great underlying illusions of the Midwest—namely, the persistent notion that whatever else happened in life, we could at least count on staying found.

But staying found was for me never much of a priority. Walking on Sunday mornings with my parents the three blocks to Our Redeemer Lutheran Church on Wall Street—face still red from scrubbing, a fresh slick of Vitalis in my hair—I often wondered why God plunked me down in such a place, on land bereft of even a good hill to scream down on a bike or a skateboard. Poster child for the topographically challenged. No one was much surprised when about age eight I started hanging out with the only vertical I could find—the giant oaks, maples, and sycamores stitched across a slice of River Park—which I climbed at every whipstitch for nothing more than the chance at a decent view. One blistering Saturday afternoon in July I scrambled down from the trees to tell my parents I needed a job of some sort, a way to fund this brilliant plan to take a big cardboard washing-machine box and fasten to it a hundred helium balloons, a buck each at the farmer’s market, thereby flying out of our postage-stamp backyard to points unknown. Lying in bed at night, reviewing the mission, in my mind’s eye I was forever looking down not on the smoke and steel of Bendix, Uniroyal, and Dodge, but across an imaginary pouf of ragged woodlots and abandoned fields to the north, beyond the Michigan border, across a loose rumple of hills with blue-green lakes puddled in their bellies.

It was about this same time, the season of my pending ascension, when sentenced one morning for one crime or another to an hour of sitting in the big stuffed chair in our living room, bored senseless, leafing through a stack of magazines, I stumbled across an ad for a Montana vacation kit. Two weeks later, a big white envelope came stuffed with maps and postcards and photos of scrubbed families in flannel shirts smiling from atop horses, and in almost every background, lines of snow-covered peaks, scary and thrilling and vertical beyond my wildest dreams. If novelist Lawrence Durrell was right, that we were in fact “children of the landscape,” then in my young mind Indiana would’ve been the pasty mother—scrunched brow, fingers forever squeezing worry from her hands. The Rockies, on the other hand, were beautiful cousin, rich aunt, and lunatic uncle all rolled into one. I was going to move West, I announced, to the Rocky Mountains, and in a new round of manic behavior set about planning an escape to Colorado for the following year—a three-thousand-mile round-trip journey, to be made on my metallic purple Sears sting-ray bike. I finally made it nine years later—made it for good—rolling up the Sawtooths in a 1964 Pontiac with the same name as John Muir’s dog.

Shortly after noon, LaVoy spots three brown lumps lying on a hillside a good half mile away. Moving cautiously we’re able to approach within several hundred yards, where we finally recognize them as three bull elk, bedded down near the head of Spring Creek. On sighting us they rise slowly and begin moving north, where they’re soon joined by four cows; the small herd then ambles together toward the lip of the plateau. Convinced the show is over we stand for a time admiring how healthy they look, the brush and color of their coats. Just as we’re about to leave, LaVoy tosses a quick glance behind us toward the head of Spring Creek and notices several animals slipping into a small ravine. Raising my binoculars to the darkest member of the group, at first I think bear. No sooner does that thought hit the ground when the black face of the lead animal turns toward me. Something else entirely. Wolves.

There are six adults—two black and four gray—all without collars, moving on what seems a certain collision course with the elk. Sure enough, partway up a small ravine the pack catches scent of the elk herd, at which point every wolf drops into stalking position. This behavior, which I have seen countless times in Yellowstone, is a reminder that, as in most predator-prey relationships, with wolves and elk there are clear rules to the game, nearly all of them meant to conserve energy. It’s not at all unusual to see wolves lope by elk with little response; let them drop to hunting posture, though, and the herd tunes up fast. In the lead this afternoon is a large black animal, likely the alpha female, and it’s her actions that control the movement of the pack. We watch her lope toward the head of the ravine, easily crossing a steep, rugged boulder field without a stumble. At the same time the other wolves shift left, and when their leader tops the ravine the startled elk double back, leaving them suddenly facing the rest of the pack. The chase is on: two elk bail off the edge of the plateau at high speed, but the wolves ignore them, choosing instead to work those that remain, singly and in pairs—running them, watching for stumbles, limps, even hard breathing, any of which could be a sign that an animal is catchable.

Not once do any of them break into high speed. The elk run just fast enough to stay ahead of their pursuers, while the wolves run only hard enough to get the information they need to size up the situation. At one point one of the bulls, perhaps bored with the whole sordid affair, turns to face the wolf that’s chasing him. And with that the wolf walks away. His fellow pack members give up at precisely the same moment and settle onto the tundra with paws in front of their faces, tongues out, panting. LaVoy’s astonished. In part for having had the great fortune to stumble across this spectacle, especially given that this is probably the only wolf pack within thirty miles. But more than that, having for years heard that wolves prey only on the weakest animals and dismissing such claims as wishful thinking, he’s seen exactly that.

“My whole take on wolves just shattered,” he says breathlessly, still trying to get his head around the idea. “This is one of the great experiences of my life.” We see the wolves again about a mile later, lying about on the tundra. Being no fans of humans, they glance our way, get up, and saunter into a shallow ravine.

In the seven years since wolves were reintroduced into greater Yellowstone, there’s never been a resident pack on the northeast side of the Beartooths. The best chance for that slipped away six weeks after the initial release, on a sage-covered hill outside the old mining town of Bearcreek, when a local woodcutter pulled a borrowed rifle out of his truck, leaned against the door, took aim, and blew the alpha male away. Shortly afterward the pups and their mother were carted back to Yellowstone and released in the park the following fall. As of this summer of 2002, there are roughly 250 wolves in two dozen groups scattered around the ecosystem, the majority living where the elk are most concentrated, on the northern ranges of Yellowstone National Park.

Wolves have now met the target populations set forth by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in the reintroduction plan, which encompasses recovery zones in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. All that’s left before they can be removed from the endangered species list (other than making it through the inevitable lawsuits) is for each state to craft an appropriate management plan—a clear strategy for how both the animal and its habitat will be managed in order to keep populations from dwindling again in the future. Wyoming is only now stumbling through theirs, having taken time out to first tend to such important matters as making claims against the federal government to reimburse them roughly four thousand dollars for every elk taken by a wolf—a monetary amount equivalent, they say, to lost hunting revenues. It’s a move with about as much integrity as a Jerry Springer guest list, especially when you consider that, at the same time, the state’s been trying desperately to reduce elk numbers in the southern Yellowstone herds. Then again, this is the same legislature that seven years ago voted a five hundred dollar bounty on wolves, then passed a law requiring the state attorney general to defend anyone prosecuted for killing one.

Idaho and Montana are further along with their management plans, though Idaho did pause long enough in 2001 to dream up RS 11108, “calling for and demanding that wolf recovery efforts in Idaho be discontinued immediately and wolves be removed by whatever means necessary.” Still, some of us are naive enough to hope they’ve left behind the antics surrounding the initial reintroduction during the mid-90s—a kind of golden era of lunacy when Idaho’s governor asserted his right to call out the National Guard and state representative Bruce Newcomb stumped for secession from the Union. At roughly the same time, Montana was busy concocting Joint Resolution Number 8, which called for the reintroduction of wolves to “Central Park in New York City, the Presidio in San Francisco, and Washington, D.C.,” as it was only those damned liberal city dwellers who wanted the things in the first place. (Proving yet again, as a writer for The Atlantic suggested in 1898, that “the Montana legislature is probably the funniest governmental body in the world.”) Never mind that in a national poll conducted in 1996 by Colorado State University, seventy-five percent of Democrats, seventy-six percent of Republicans, and eighty-two percent of independent voters were in favor of the reintroduction; closer to home, in the northern Rockies, opinion was split roughly in half. And finally, there came that brilliant attempt at prescience by Montana U.S. Senator Conrad Burns, who told educator Pat Tucker, “Little lady, mark my words, if they put wolves in Yellowstone, there’ll be a dead child within a year.”

People often ask me if negative attitudes about wolves in the region have changed since the reintroduction. Some of my rancher neighbors confess to being relieved, glad to have been wrong about how bad livestock predation would be. But it’s hardly the sort of thing they’d admit in public. In fact, unless you’re up for a blistering argument, it pays to think carefully about what comments you happen to toss out about wolves, and where. To this day you’d probably sooner get the crap knocked out of you for walking into the Bullsitter Lounge in Cody with an “I Love Wolves” T-shirt on than by standing on the bar in a bin Laden T-shirt trying to recruit members for al Queda. An hour or so after the second wolf sighting, we stop to catch our breath on the eastern edge of the plateau, pull out our binoculars, and, in seconds, spot nearly two dozen nanny and kid mountain goats dancing down a sheer wall of igneous rock near Line Lake. Barely two days out and already we’ve stumbled into a wildlife cabaret. Toss in a grizzly and a moose and we’ll have a grand slam. Of course, while many such encounters are pure luck, some of our success has to do with LaVoy’s method of travel—that of a hunter, walking always slowly enough to look around, pausing often to sit with his elbows propped on his backpack for a careful glassing of the distant hills. The kind of movement I imagine having once been fairly common, but today so rare as to make it something of an oddity.

We continue this blissful ramble through much of the third day—until lunch, anyway, when we gain a lonely ridge in the Beartooths high above Littlerock Canyon. In a nearby bog, miles from any discernible road, is an abandoned 1947 Chevrolet Stylemaster mired up to the axles. Picked clean of usable parts, sandblasted by the wind, and overwhelmed by the terrain, it seems a comforting monument to the limits of machines, a reminder that even General Motors can be stopped by nothing more than a good wet spot in a high meadow. It’s right here, a stone’s throw from the middle of nowhere and with more than a hundred miles still to go, that the scope of our journey finally begins to sink in. Westward from this windy perch is a daunting vision of the snow-covered Absaroka Mountains. Exploding from the Earth on the far side of the Clarks Fork Valley, they are both beautiful and awesome, a range born of ancient seabeds—the eldest some 350 million years old—later covered by volcanic flows, those in turn eroded by mudflows and water and ice. Without question this is one of the most rugged stretches of high country anywhere in the Rockies. We stare out at the peaks through bites of jerky and cashews and cheese, and all the while they manage to both thrill us and break our hearts. From where we sit there’s no hint of any sort of reasonable passage. Yellowstone, lying on the far side, seems all but out of reach. So we procrastinate. Which for us means launching into yet another prolonged My Dinner with Andre kind of conversation, talking of things both lunatic and inspired. The kind of exchange trapper Osborne Russell was fond of, often referring to it as the Rocky Mountain College. Over the past few days LaVoy’s stories have been spilling out all over the tundra—more tales than Carter’s has little liver pills, as he would put it. This is what I know so far. His crippled right arm was damaged at fourteen when, on a bet from friends, he roped a cow high on locoweed. The cow charged the horse, and in the ensuing fracas the rope got wrapped around his right arm, nearly severing it, permanently damaging the nerves. He’s got a little use of the fingers on that hand, but not much. His parents, utterly devastated by the accident, hauled him to one doctor after another, each one assuring the family that the cure was close at hand, one failed surgery or therapy leading to the next, until finally, two years later, LaVoy himself put a stop to it. Even with the injury he remained remarkably athletic, playing baseball by mastering a tricky maneuver of catching the ball using his good left arm and then instantly removing the glove to throw it with the same hand. (So good was he at this little juggling act that in his final year of high school he was scouted by the pros; the scout liked what he saw, but in the end decided the injured arm didn’t allow LaVoy to get enough muscle in his batting.) There was track and wrestling, too, and in college, a boxing stint that led eventually to an invitation to the Golden Gloves.

LaVoy’s story is more, though, than just another tale of boy makes lemonade out of lemons. In the wake of the roping wreck, LaVoy saw a lot of so-called friends distance themselves—turn their backs and even snub him—for the most part because the accident left him looking different, and in high school different is an almost unforgivable circumstance.

“I’d always stood up for the underdog,” he says, explaining how before the accident he’d be the one to throw in with the weaker kids at school, helping them stand up to bullies. “Now all of a sudden it was me. I was the underdog.”

We press on toward Littlerock Canyon, picking up our first obvious path since climbing Mount Maurice on the morning of the first day. The trail drops across open slopes dotted with cow elk and their rust-colored calves, turns south, and then finally heads west through slotted canyons filled with the chatter of fast-running creeks. Once off the tundra the heat comes on, wearing us down, until by the end of the day we’re grimy and bedraggled, sweating up a long, steep run of sopping meadows. It’s well after seven o’clock when we finally gain a small crest and call it quits on a rock-strewn tableland cupping Top and Dollar Lakes. The woods, as well as the north faces of the rumpled hills, are thick with wedges of snow; thin sheets of meltwater are coursing across the ground, leaving barely enough dry land to pitch a tent. As yet there are few mosquitoes, though that’ll no doubt change fast in the days to come as nighttime temperatures creep back above freezing. I’m tired as hell and LaVoy is close to shot. Two months from now he’ll look back on this day as the hardest of the whole summer.

Sitting around the stove waiting for the water to boil, tearing at pieces of jerky, LaVoy pulls back the covers on his childhood again, this time focusing on a favorite topic—his animals. He tells of a certain gelding named Dusty his family captured from a herd of wild horses roaming the high desert not far from his home in southern Utah. One day he and his dad and uncles were out riding near the wild herds again when Dusty—traveling without a rider—sighted his old mates, tore loose, and started running, coming alive as if by magic, herding mares as if he still had all his original equipment. LaVoy chokes a little on the memory, tells me it broke his heart to see the way that horse slumped at the end of the day when the bridle went back on, that the mere sight of it caused him to make some conclusions about the worth of freedom.

And then there was Spot. The stupidest dog in Millard County. Supposedly a hunting dog, but one that couldn’t be trained if his life depended on it—running ahead of the shooters, ignoring commands, bolting at the sound of gun fire to cower under the truck. But sixteen-year-old LaVoy noticed something about that dog that everyone else missed, namely that here was a critter with an incredible nose. Time and again he watched as Spot picked up the scent of birds hundreds of yards away, then walked right to them. Describing what he says was one of the most important lessons of his life, LaVoy decided that instead of getting in a twist trying to teach the dog to hunt in the conventional way, he’d instead adjust his own behavior to match the dog’s talents. Who cared if Spot drifted out ahead, found the birds, and just stood there until the hunters finally caught up. Let him do it his way. In no time LaVoy was fielding calls from his uncles, from all his dad’s friends, every one of them asking if they could come hunting with Spot.

Sitting on this rock, stirring a pot of soup, it dawns on me that LaVoy is one of the few men I’ve met who talks openly about the insights he gained as a kid. Maybe it has something to do with all the time he spends in the wild. The truth is that even the most distant man seems somehow more willing to fly his daydreams when his chest is pinned under some big, lonely expanse, under black skies shot full of stars. While women are able to take what happens on the job, at home, in the garden and weave a religion out of it, guys seem prompted to such inspiration mostly when they’re adrift in some grand stewpot of metaphor. Men are epic junkies. Responsive to those times when life is crushed only to rebound right before their eyes—as so often happens out here, one season trampled by rockslides and windstorms and blizzards, the next rising in a wash of leaves, in great clatters of geese dropping from the sky.

LaVoy’s life has long been tethered to such metaphor—not just when he was a kid, but across some forty years as a high school science teacher. I recall first meeting up with him in the field as he was squatting under a juniper beside a group of fifteen-and sixteen-year-old girls, students from that wilderness therapy school, ostensibly teaching biology.

“Remember those big mushrooms we ran across earlier today?” he was asking them. “We called them puffballs, didn’t we? Well, those puffballs are a good example of life reproducing by spores, millions of them, each one exactly alike.” I listened as he then slowly, and with great patience, drew out their ideas about what might be the limits of such a reproduction strategy.

“If I’m understanding you right,” he finally said, “the only chance a puffball spore has for success is to land in exactly the right environment. The same conditions as the parent plant.” Then more discussion, with the girls concluding that most life doesn’t clone itself like that at all, but reproduces sexually—a strategy offering nearly limitless potential for variety. And that with variety comes a better chance for a species to flourish in changing circumstances. “So what you’re really saying,” he summed up, looking each girl in the eye, “is that nature loves diversity.” And in the days that followed that session I watched girls who just weeks before were bleeding from the jagged edges of all that had broken in their lives, staring out past the ponderosa onto the magnificent red rock of Capitol Reef, letting out breath, gathering up the pieces.

Summer in the northern latitudes brings the chance to swim in daylight—a good seventeen hours of it, more if you count the powdery blush that comes on in the east before dawn, or the shimmer of alpenglow, which these days lasts well past ten o’clock. Despite the hard trek yesterday, we rise shortly before 6 a.m., by 6:30 are packed and moving, choosing always to eat breakfast down the trail a mile or two or three, when the blood is flowing and the kinks are out—when Arthur, as LaVoy calls the arthritis in his feet, has been all but forgotten. Yesterday I told him I was feeling acclimatized, better adjusted to life two miles up, but he looked doubtful. “You never really get acclimatized,” he said. “You just get used to the pain.”

By most standards we’re traveling light, forty-five pounds for me and barely forty for LaVoy. I’ve spent two months dehydrating food—everything from spaghetti sauce to salsa, from chicken curry to spinach-lentil soup. An hour or so before eating we pour the dried meal into a quart Nalgene bottle, add water, and walk on; with the jostling of the final miles comes dinner, ready to heat and serve. Besides rain gear and Capilene underwear we carry a few first-aid items, including moleskin and Spyroflex for blisters, some jerky and gorp and a water filter, notebooks, a camera, binoculars. Because we typically eat before getting to camp (thus keeping the smell of food well away from us), the routine at the end of the day is easy. Fifteen minutes to set up the tent and pull out headlamps and notebooks for journaling, ten more to brush our teeth and hang the food bag.

Tonight I’m recalling some hiking advice offered by a stalwart, if snippy, little adventurer by the name of Hanford Henderson. In 1898, Henderson became one of the few people to ever walk the entire loop from Mammoth to Lake to Canyon and back, a journey of more than a hundred miles. Traveling by stage the trip took six days; Henderson did it in five. To walk successfully, he wrote, one has to attend to certain details, the most important being one’s dress.

The common mistake is to wear too heavy clothing and too much. Better venture upon the trip, as I did, wearing the lightest underclothing, a summer traveling suit, a straw hat, and light shoes. A special caution is needed against heavy shoes. They have wrecked many a promising expedition. It is much better to go tripping daintily along, picking one’s way, if need be, than to wear tiresome clod-hopper shoes, and step on every sharp stone you see. In my hand I carried a light umbrella (to kill rattlesnakes and frighten off bears) and a modest little paper bundle, in my pocket a package of soda crackers, in my heart many things. Nevertheless, it was very light. This is also important.

Curiously, Henderson wasn’t the first to employ an umbrella for protection against wildlife. Theodore Roosevelt relates the tale of a man in Yellowstone trying to see how close he could get to a sow bear with cubs, only to have the animal chase him down and issue a severe bite. The fellow’s path of escape was directly at his wife, who simply brandished her umbrella and beat the bear away. Likewise, a nineteenth-century Montana hunting guide by the name of Farrell routinely traveled not with an umbrella, but with a wooden stick, claiming that “a crack on the nose is worth a dozen random rifle shots.”

All the next day we spend leaving the Beartooths. It begins with a quiet walk on a jeep road thick with snow, where we spot our first grizzly tracks, followed by an icy ford of the outlet at Chain Lakes, all the while massive cutthroat trout swimming around our legs. The views to the north are extraordinary. This is the very heart of the Beartooths—colossal turrets and parapets of granite rising some two thousand feet, blanketed in more snow than I’ve seen in years. Of all Montana’s mountains, these are the ones most likely to crank their own weather, producing squalls and blizzards in every month of the year, freaking out summer visitors from Iowa and Kansas and Michigan steering their giant RVs down the Beartooth Highway, tightening fists and twisting faces, creating a brisk trade in brake repair for mechanics in Red Lodge. Whatever poetry there is in these tumbles of rock is on many days less meter and rhyme than feral, howling free verse. Only now and then does Robert Browning’s rosy earth show itself, his lovely, bucolic dew-pearled hillsides. More often it’s Whitman, Ginsberg, maybe Gary Snyder: “Ice-scratched slabs and bent trees, / … / Only the weathering land / The wheeling sky, …”

It’s been just over a hundred years since eight men huddled around a campfire northwest of here, outside the village of Cooke City, Montana. Fresh in from the East they’d come with the charge of making the first in-depth geological exploration of these mountains, known at the time as the Granite Range. In the group was a rough and ready Norwegian photographer named Anders Wilse, a couple of engineers, and a few bearded, fly-bitten hunters and horse packers. And the guy in charge of the show, mineralogist James Kimball, a wad of Rockefeller’s money in his pocket.

Not that they were the first rock hounds to show up here. Geologist William Holmes had been in these mountains twenty years earlier, part of Ferdinand Hayden’s 1871 survey of Yellowstone. But his reports on the Beartooths had mistakes in them, big ones, leaving Kimball thinking that the guy never really visited the heart of the range at all. And then there’d been General Philip Sheridan in 1882, marching east out of Cooke City past Beartooth Butte, down Line Creek Plateau, and on to the Yellowstone River. But Sheridan was simply doing what he did best—making time, dreaming up roads. The way Kimball figured it, the job of exploring the region was still to be done and he and his partners would be the ones to do it. Sitting around the fire, the men’s spirits were high. The final weeks of summer lingered before them like a good dream.

What the party didn’t count on was Beartooth weather. On they plodded, making one wind-blasted day trip after another into the unknown: to the head of the East Rosebud, to Lake Abundance and the Stillwater and the Sawtooth summit, up much, but not all, of Montana’s highest mountain, Granite Peak. Kimball’s descriptions are a mix of scientific jargon—talk of porphyritic dykes and feldspathic granite—and boyish thrill at the steep gorges choked with rocks, ice-formed lakes, and waterfalls by the dozen. And always the “treacherous weather—pelting hailstorms, bleak winds,” including a bivouac at Goose Lake that would leave him for years afterward referring to the place as Camp Misery.

Kimball’s party progressed by splitting up observation chores. As often as not the photographer Wilse gathered his heap of heavy equipment and set out alone across the most rugged of the terrain, ripping his boots and clothes to shreds on the sharp rocks, carrying only a wool blanket and a sack of food, sleeping at night by plucking stones out of the tundra for a patch of grass flat enough to lay down on. It was Wilse who stumbled across the ice field full of frozen grasshoppers that a handful of local hunters and miners had told the party about, a rather famous feature eight miles north of here known as Grasshopper Glacier.

The snows of autumn came early that year, in a few days piling into drifts several feet deep. To their great disappointment the team was forced back to the lowlands, even though there were big tracts of the northern range still unmapped. The trek out of the high country was so difficult that Wilse and an engineer named Wood were assigned the job of scouting ahead of the party for a way out, peering through sleet and snow to locate suitable campsites along the way—preferably near marshy areas so the horses could kick down through the layers of snow to find grass. On the evening of the last day, with the view of the brown, dry prairie stretching before them to the east, Wilse and Wood had an argument about the best way to reach Red Lodge; they split up in a huff and began making solo descents. Wilse and his horse—a tough mustang with the not-so-tough name of Pussy—had a real time of it. In a diary written years later he describes levering rocks from the snow-covered slope and sending them crashing down the mountain, thereby creating a path on which he could slide down on his rear end, while the horse skittered and scrambled as best he could. It was past dark by the time they reached the bottom, covered in sweat. Meanwhile the rest of the party was stuck topside, buttoned down against sixty-mile-an-hour winds. A single tent was finally erected, but the lone person who chose to sleep inside spent the whole night trying to keep the canvas from collapsing against the hot stove, which it did anyway. The next day the party missed the Rocky Fork altogether, landing instead in Wyoming’s Bighorn Basin.

Amazingly, following a brief rest at Red Lodge, Kimball and a small party, minus Wilse, took on additional forays in and around the Beartooths all through the month of October: over Dead Indian Pass Road, the sides of which were piled with “snubbing” logs—trees that had been cut and tied behind wagons to keep them from careening out of control on the two-thousand-foot, mile-and-a-half-long descent; back around the Beartooths to the East Rosebud, where Kimball watched in horror as eighty-mile-an-hour winds destroyed his twelve-by-sixteen-foot wall tent, tearing the eyelets out of the fabric and sending clothes, bedding, and even the woodstove flying down the canyon. “Everything had soared away,” he wrote, “except blankets under the weight of their possessors. Minor articles, usually worn in pairs, never found their mates. No further adventure proved necessary to force the conviction that endurable conditions for camp life had come to an end for the season.”

As for me, it’s in the Beartooths where I’ve gathered the lion’s share of my best memories. Up at ten thousand feet with a full moon over some nameless rock-bound lake, mountain goats skimming the edges of camp. Storms coming up as if pulled from a hat, sending me running for the lip of the tundra. Windless dawns propped on an elbow in a bed of forget-me-nots, looking across some fifty miles of nearly empty space at the Crazy Mountains burning in the sun.

On day four, we leave the beaten path again around one o’clock, plotting a long compass line through the forest over Table Mountain to the Chief Joseph Scenic Highway, hoping to come out at a place called Painter Store. My wife, Jane, will be there, planning to toss on a pack and hike with us for fifty miles into Yellowstone and up the Lamar River, then into Pelican Valley, coming out near Yellowstone Lake at Fishing Bridge. What we hadn’t planned on is Beartooth Creek, just west of Table Mountain—a stream turned insane with snowmelt, rocketing wall to wall through a series of dark volcanic slots, a deadly watercourse that no one in their right mind would consider crossing. We’ve been told there’s a bridge downstream, but when we get to the drainage we find the only tolerable walking to be well away from the creek, which leaves us too far back to see anything. Missing the bridge could take us miles out of our way, leaving us snarled on the banks of the Clarks Fork in a canyon that a skilled mountain goat would be hard-pressed to navigate without ropes and pitons. So we stick close to the east bank of the creek. The channel is pinched by a long series of steep, rock-bound hummocks fifty to one hundred feet high; in between are short stretches littered with downed timber, leaving us constantly climbing over, under, and around. The heat is blistering and the mosquitoes have popped out of their watery nurseries to feast on us, mustering their greatest resolve in those moments when I happen to be fully compromised, on my knees or, better yet, on my belly, squirming under downed lodgepole.

After more than an hour of this we spot not a bridge, but a colossal logjam. Four enormous trees lie in a tangle, their bark ripped away by floodwaters, the wood polished to an ivory shine. Underneath is a riot of white water, shouting and shaking not just the logs but the very earth around them. Climbing onto the leading edge requires some acrobatics, and at one point LaVoy actually ends up wedged between two large branches, leaving me having to push like hell to get him through. Of course there’s a big difference psychologically between balancing yourself on a log across some dinky creek that might soak your feet and chill your pride and doing it over something that will drown you should you tumble to the upstream side or, should you fall downstream, knock you senseless and rip your pack to shreds in a rock-strewn canyon. When we finally make it over I park myself for a few minutes to get my heart out of my throat. Three more miles to Painter Store, which as luck would have it is closed due to a power outage. But Jane is there. And a bench in the shade. And a cooler full of food.