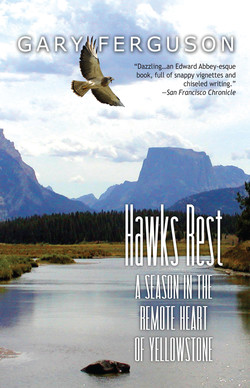

Читать книгу Hawks Rest - Gary Ferguson - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPrelude

MY FINAL MORNING IN THE wilderness and it comes on the cold, bright spine of autumn. Mid-September, when beauty and death are joined at the hip, storming across the high country and filling the swales of the northern Rockies until the days seem too small to hold them. Thick, warm afternoons followed by frigid nights. Not a single morning breaks without the edges of streams and rivers being rimmed with ice—the upper Yellowstone, Thorofare, and Fall Creeks, the South Fork of the Shoshone; long before dawn, fireweed and lupine, gooseberry and harebell sag with frost. So too does ice form in cracks in the rocks, popping chunks of breccia off mountain faces. And then the wind, by noon full of bristle, stinging the tundra, cracking loose lodgepole pines burned in the 1988 fires, felling them in loud shots like the sound of the hunters’ guns.

The days are swelled with signs of going. Canada geese honk and strut up and down the canyons of the South Fork, restless and quick to hush; songbirds and hawks, a few here and a couple dozen there, slip southward on some unknown signal, leaving the rest of us to nearly empty skies. In the mountain valleys to the west elk are massing, the bulls bugling and snorting, restless with the fever of the rut. In the wake of the first big snows they’ll come pouring out of Yellowstone by the thousands. Some will head south, making for the National Elk Refuge near Jackson, or feeding grounds in the Gros Ventre Range. Others will turn east—traveling in my footsteps, as I’ve been traveling in theirs moving up Thorofare Creek and over the divide into the South Fork, up the sheer western flank of Needle Mountain and on to the windswept valleys of the Greybull River. One of the longest migrations in the Rockies.

Over the course of the summer dozens of visitors asked me what I missed, what I craved most living in a patrol cabin for eleven weeks in the wilds of greater Yellowstone far from the drone and clatter of engines and fax machines and phones. I never managed much of an answer. Even now, on the brink of my return, it’s nearly impossible to slip out of the present—as if the Absarokas were charmed, demanding always full attention, causing travelers to nearly forget who they were in that other world. Part of the spell comes from overwhelming beauty—great platefuls of it, full of wobble and swoon. It comes too from the fact that in every month are sharp squalls of snow and ice crashing across the high country, and in the heart of a great many summer afternoons lightning literally buzzing in the rocks. And then of course there’s the grizzly, out in force now, charging about in that fiery state biologists refer to as hyperphagia, a kind of eating frenzy that begins each fall before the onset of denning. The fever may be even more intense this season given that one of the bears’ favorite foods, the nuts of the whitebark pine, are in short supply, the result of drought and a tenacious, widespread disease known as blister rust; evidence of the infestation is everywhere, miles of brown branches smeared across the shoulders of the mountains.

In truth there’s almost no end to the ferocity of this place, a wildness that tugs and shapes everyone who spends any amount of time here, on occasion wrenching them into something bigger than life itself. Even the names of some of the regulars make them sound like mystics, superheroes: Lone Eagle Woman from Wyoming, for example, who for the past twenty years has been wandering alone each summer across the high reaches of the Absarokas—as much at ease sleeping in these far-flung crannies as most people would be wrapped in their childhood beds. Or Yellowstone park ranger Bob “Action” Jackson, growing more famous by the month—in part for his battle with outfitters over the illegal use of salt to draw elk across the park’s south boundary and, at the same time, for his fight with a Park Service that can no longer abide his provocative ways. And then there’s that certain Bible-thumping, gun-slinging, illegal outfitter whose name is rarely mentioned at all, a feral and dangerous sort—out there long after the season has ended in the worst of mountain weather, going about the business of, as he puts it, hunting for God.

Grizzly bears and bouts of brutal weather aside, most people would probably imagine this place, the most remote in the lower forty-eight states, to be largely untroubled, unruffled, serene. I’d thought so too, coming here in large part to do the work of a naturalist: record bear activity; make notes on the comings and goings of the Delta wolf pack; take the chance to explore the rise of new forests from the ashes of old burns; appraise populations of everything from white pelicans to eagles, moose to cutthroat trout; gauge the swell of berries in the lowland woods, rootstalks on the tundra. Not that I expected complete seclusion. It seemed a safe bet, though, that the roar of the land would be more than loud enough to overwhelm the comings and goings of humans. And yet there were simply too many of them, sometimes hundreds in a given week, flush with tents and lanterns and dogs, with long strings of horses and mules.

But beyond sheer numbers, I’m leaving today having come to know this vast twist of peaks and valleys as a kind of sanatorium for the disenfranchised, a way station for men riding and hiding, spring through fall, to escape whatever curses they imagine hovering in the culture at large. In these upper meadows of the Yellowstone is testosterone enough to light the woods on fire. Wanna-be cowboys roam the highlands by the dozen, each with at least one gun on his hip—angry, hating wolves and the government that reintroduced them. And more conspicuous still, an outlandish strain of outfitter, swaggering down these dusty trails and thumbing his nose at authority, living a kind of desperado fantasy that seems more appropriate to the nineteenth century than the twenty-first.

“This is a lawless place,” a veteran trip leader told a young Forest Service worker this summer about the outfitters in the area, comparing the place to the days of cattle rustlers in old Wyoming. “If I were you I’d consider a career in law enforcement. One day somebody’s going to get hurt or killed back here and all hell will break loose.”

In the 1840s there was an argument being made by nationalists eager to settle the more remote places of the American West: without the gentling hand of civilization, they said, people would spin off, unleash all sorts of peculiar and unholy behaviors. Maybe so. Yet at the same time the vast majority of Native Americans thought it perfectly normal for beauty and craziness to stand together like this, arm in arm—two sides of the same leaf. Which may be closer to the truth. Or at least the truth as it shows itself here, in this far northwest corner of Wyoming, on the ragged edges of the Great Divide.