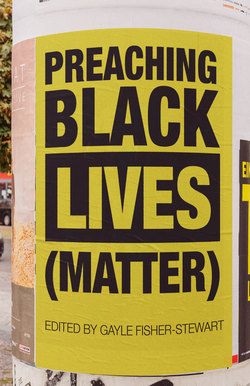

Читать книгу Preaching Black Lives (Matter) - Gayle Fisher-Stewart - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

Christmas: A Season of Peace?

A CHRISTMAS MESSAGE TO THE UNION OF BLACK EPISCOPALIANS

Nathan D. Baxter

I don’t know about you, but my heart is very troubled this Christmas. Recently an article that included photos of my participation in a march for Black lives in 2012 came to my attention. Looking at the picture, I realized that I am still troubled as a Black man—a husband, father, uncle, and grandfather. I am also troubled as a Black man who claims the Christian faith. I look around me and I see Black-on-Black gun violence, and blatant police violence on young men and women of my community. I see Black domestic violence yoked with entrenched poverty.

I see a political-economic system of school to prison tracking of our Black youth. And even with (if not because of) a Black man in the White House, I see a growing constitutional movement to reverse many hard-won civil rights and protections. I think many of us feel as insecure as did our ancestors during the days of the Fugitive Slave Act. We are not safe from racist violence on our streets and highways, nor even in our houses of worship. In my heart I feel deeply the protest chant, “NO JUSTICE! NO PEACE!”

Yet, I am a person of Christian faith—a faith that calls me to a heart of peace even in the midst of injustice.

Our Lord Jesus said, “But what comes out of the mouth proceeds from the heart, and this is what defiles. For out of the heart come evil intentions, murder, adultery, fornication, theft, false witness, slander. These are what defile a person” (Matt. 15:18–20).

Yes, I know in my heart that Christians must seek inner peace, lest, in the struggle for justice, we become the evil against which we struggle.

I am a Christian. But even more, I am an inheritor of the Black Christian tradition—a theological tradition that transcends denominations. One cannot listen to the words and melodies of the spirituals and not recognize that our slave ancestors’ struggle for freedom was anchored in an inner spiritual peace. One cannot think of the civil rights movement, its songs and sermons, and not recognize that the strength to face and overcome Jim Crow’s evil was drawn from an ancestral understanding of the King of Peace: “Ride on, King Jesus.” We call this “Soul Theology,” which means we shall overcome only by keeping our souls anchored in the peace of Christ, even before justice comes. In this sense, the protest motto, “No Justice! No Peace!” is inverted to “NO PEACE! NO JUSTICE!” “Soul Theology” understands the essential divine truth that peace must be a matter of the individual heart before it is a social, cultural, and political reality. Keeping one’s soul anchored is for us both a divine truth and ancestral witness.

The greatest contemporary witness of this aspect of “Soul Theology” was seen in the aftermath of murders at Mother Emanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston, South Carolina. The entire nation and world were stunned when family members repeatedly stressed forgiveness of the perpetrator. Their sentiments were summed up by Wanda Simmons, granddaughter of victim the Rev. Daniel Simmons:

Although my grandfather and the other victims died at the hands of hate, this is proof, everyone’s plea for your soul, is proof that they lived in love and their legacies will live in love. So hate won’t win. And I just want to thank the court for making sure that hate doesn’t win.1

As Black Christians, they also understood the importance of inverting the great protest motto to say, “NO PEACE! NO JUSTICE!”

Perhaps this Christmas we should recapture the important message of Langston Hughes’s play Black Nativity and remember that God made an ethnic specific statement, sending Jesus, a Jew, in a particular social location. It was God’s way of saying “Jewish Lives Matter.” From that specious reality came the universal witness that all lives matter. So, too, we must seek in our own realities “A Black Nativity.” As critic Peter Simek wrote, “Langston Hughes’ Black Nativity takes the biblical Christmas story and filters the scripture though the cultures of Diasporas Africa. . . . He picked up an ancient Christian tradition of adaptation and appropriation, removing the Germanic tree or the Italian crèche and replacing it with an African drum and a Harlem voice.”2

We will see many crèche scenes this year, signs of God’s peace in a violent and desperate world. Can we see our particular Blackness in the scene, our particular source of peace in the struggle? Can we filter the sacred story through our own culture, our own experience, our own social location—give it the sounds of ancestral rhythms, a community’s voice of protest, and a Soul’s Theology of peace?

I began this message by sharing the photographic discovery of my angry self in a “Black Lives Matter” march for justice and peace. But later in the article I saw another sobering image of myself in a softer scene. I am still walking the protest march but now with some children who had gathered around “the priest in a dress.” As we made eye contact, smiled, and chanted slogans, I noticed in them something I had not when I was walking with other ministers and adult activists. It was a peaceful determination, a sense of empowerment from being in the midst, a kindred community. So many had not known how diverse and united our local community could be. It was, in a sense, a Black Nativity. They were surrounded by mothers and fathers, pastoral shepherds, political wise men and women, and prophetic activists. Like the Christ Child, our Black, vulnerable children were courageously radiating among us—peace in the chaos—and an affirming hope in the struggle. I remember knowing in those moments that God was present. Incarnate.

This year let us share with one another the Nativity gift of peace, even as the struggle for justice continues. And let us remember the promise of our Prince of Peace: “Peace I leave with you; my peace I give to you. I do not give to you as the world gives. Do not let your hearts be troubled, and do not let them be afraid” (John 14:27).

Merry Christmas.

1. Elahe Izadi, “The Powerful Words of Forgiveness Delivered to Dylann Roof by Victims’ Relatives,” The Washington Post, June 19, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-nation/wp/2015/06/19/hate-wont-win-the-powerful-words-delivered-to-dylann-roof-by-victims-relatives/.

2. Peter Simek, “Does the New Black Nativity Retain the Heart of Langston Hughes’ Classic Story?” dmagazine, November 27, 2013, https://www.dmagazine.com/arts-entertainment/2013/11/does-the-new-black-nativity-retain-the-heart-of-langston-hughes-classic-story/.