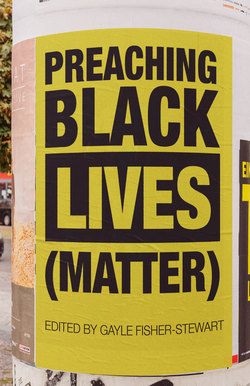

Читать книгу Preaching Black Lives (Matter) - Gayle Fisher-Stewart - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление7

Strategies of Resistance

DANIEL 3:14–20, 24–29

Wilda C. Gafney

There is more than one way to tell a story, especially a story as important as the Christian story; this also applies to the stories that make up our sacred stories. Today we explore that plurality in a lectionary of my devising, rather revising—because I think there is danger in only retelling the same stories, no matter how beloved.

Among our sacred trove of stories are two versions of the Daniel story; even more exist outside of the Christian canons. One of those canonical stories was preserved in Hebrew and Aramaic by the descendants of the Judeans who survived the Babylonian exile and created the mother text for the Hebrew Bible and the Protestant version of the story. That is the source of our Second Lesson and Canticle. The other canonical story was preserved in Greek by the descendants of the Judeans who fled to Egypt instead. That is the source of our First Lesson. Together those lessons and canticle are in narrative order telling a more complete story.

The book of Daniel is a text of resistance. It is a cagey, strategic piece of resistance. It is an anti-imperial text disguised as an anti-imperial text. Empires don’t mind their subjects mocking failed and fallen empires. In their egocentrism, they read that calumny as their own praise because they are top dog now. So the cagey authors of Daniel disguised a critique of the lingering and declining Greek Empire in a retroactive critique of the centuries-past Babylonian Empire. And they put that critique on the lips and at the pen of Daniel, a beloved figure whose origins were even older than the Babylonian Empire, or its predecessor Assyrian Empire, or the great dynasties of Egypt, or even the founding of the people of Israel. Daniel was a figure of legend whose stories were told in each generation with new stories added to his canon from time to time.

I invite you to hear the story as subversive as it really is. In the First Lesson, three young people have been taken captive by the empire and forced to assimilate to its culture, made to wear its clothing, eat its food, speak its language, and answer to the names they give them—names which stuck to them even in the stories of their own people. The tentacles of empire reach deep, even into the hearts of people who are working faithfully to decolonialize themselves. It matters that these are young people. In the larger story of Daniel, they are taken as children to be assimilated so that they will love the empire that colonized their people more than they love their own selves. Empires have always underestimated young people, whether it was civil rights protestors, dreamers, or high school gun reform activists.

When our lesson begins, these young people are being enculturated in the worship of the empire and required to pray to the gods of the empire at the cost of their subjugated, colonized lives. One of the lessons of this text is that empire is rapacious and insatiable. They were already speaking the language of empire. They had already had their names changed from Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah to Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego. But it wasn’t enough. The empire wanted more—more of them, more of their souls.

As long as there is a corner of your soul that is free, uncolonized, unconquered, unbought, and unbossed, empire will by any means necessary seek to uproot that liberty and colonize the last vestige of your right mind, heart, and soul. African and Native Americans know this story all too well as do the indigenous peoples of every nation conquered by an empire. In the face of the empire’s ravenous desire for their abject and total submission, Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah clung fast to God of their foremothers and fathers and rejected the empire’s religion.

I’m calling this sermon “Strategies of Resistance”—ours, not theirs, because they didn’t really strategize. They just said no. No to the god of empire. No to its worship and veneration. They didn’t negotiate; they didn’t equivocate. Sometimes we just need to say no to the manifestations of empire in our world. No to the slaughter of school children. No to military-grade weaponry in the streets. No to families ripped apart by militarized immigration assault troops. No to bad preaching. No to death-dealing theology. No to violence against women. No to bullying gay and trans teens to death. No to incompetent and corrupt government. No to everything that stands against the life-giving love of God and the liberty it grants. No and hell no.

The empire responded to their rejection of its attempt to colonize their minds, their spirits, their souls, and their ancestral religion with lethal rage. The empire covets good religion. It knows if it gets a toehold in pulpits and pews, seminaries and sanctuaries, books and blogs, texts and tweets, it can sanctify its hierarchies and disparities as the word and will of God. The empire prepared to kill Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah. It was to be a spectacle lynching. A spectacle lynching was when good White folk would make an event out of a lynching, bring their sweethearts, wives, children, and a basket of goodies to nibble while they watched the show. They’d often set their victims on fire (as Nebuchadnezzar planned to do), pose with their burning corpses, and later cut off pieces of them to take home as souvenirs.

Activist-archivist James Allen collected one hundred and forty-five photos of spectacle lynchings in the US. They are featured in the volume Without Sanctuary1 which I commend to you. The strategies of resistance required to outlaw lynching lasted well into the twentieth century. Sometimes resistance is an intergenerational struggle.

The most significant strategy of resistance employed by the three young people was the willingness to let the empire spill their blood. Sometimes resistance means being willing to die. Sometimes it means preparing to die. Sometimes it means dying. Sometimes it means rising from the dead—but I’m getting ahead of next week’s story. We are not far from the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination and martyrdom of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. He and many others in the civil rights movement resisted not just segregation but White supremacy with their very lives. White supremacy is a colonizing force that transcends national borders and is every bit as much a manifestation of empire as any nation with imperial imagination and aspirations. The three young people prepared to die in resistance to the empire.

The Hebrew text moves quickly to a story of miraculous deliverance, but not so fast—there is more to the story. The Greek story picks up where the Hebrew one leaves off and fills in the gap. The young people responded to their impending extrajudicial killing with the songs of their ancestors. They sang to the God no empire could strip from them. They told the story of God’s faithfulness to their people. As the empire’s rage burned against them in literal fire, they used the breaths they thought would be their last to deny the empire power over them, over their story, and over their song, because our stories and our songs are tools of resistance. The empire set out to destroy this last act of resistance. But something happened when they refused to surrender their heart and minds, songs and prayers, poetry and theology, even if they had to lay their bodies down. God appeared in the midst of the resistance.

The resistance writers used the book of Daniel to tell their people that the empire would not be defeated with the master’s tools. They couldn’t defeat it with military might. They couldn’t defeat it with economic might. But if they kept their minds right and stayed on the God who delivered their ancestors, no empire would ever be able to destroy them, no matter what their political reality. In the words of the Gospel, “you will know the truth, and the truth will make you free” (John 8:32).

Our words have power. That is why fascists burn books, ban films, silence scholars, censure artists, and assassinate prophets. They bully and sue, intimidate and obfuscate, and they use their words to rewrite our stories, revise our histories, and stamp their image on our art and culture. And they lie. They lie about us. They lie about our culture. They lie about our history. They lie about God. With their lies they construct a god who is not God and expect us to bow down and worship it.

But these young activists on the page and the older activists behind the pen have shown us how to resist: Don’t let the empire tell you who you are. Don’t let the empire assimilate you into its culture. Don’t let the empire tell you your cultural and culinary practices are inferior. Don’t let the empire clothe you—body or mind. Don’t let the empire tell you who God is. Don’t let the empire use your life to advertise its glory. Resistance is not futile. But resistance is costly. We follow one who resisted empire to the cost of his life and we are called to do the same. How much more ought we be willing to put our lives on the line knowing the promise of resurrection than those young people, literal or literary, who were willing to go to a death from which they had no sure promise of escape? Amen.

1. James Allen, Hilton Als, John Lewis, and Leon F. Litwack, Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America (Twin Palms: Twin Palms Publishers, 2000).