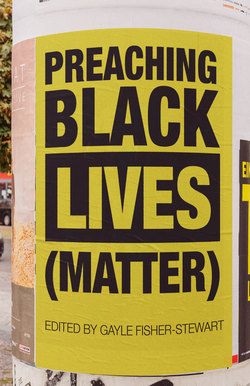

Читать книгу Preaching Black Lives (Matter) - Gayle Fisher-Stewart - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеBeginning Words

Kwasi Thornell

The Rev. Dr. Kwasi Thornell was ordained an Episcopal priest in 1972. He has always pushed the envelope of what it is to be Black and Episcopalian. We are called to remember our roots, remember our heritage, who God has created us to be, and bring all of that to the Episcopal Church. In his own words . . .

It was a beautiful day on that Saturday morning in Chicago in 1989. People had come from all over the country to St. James Episcopal Cathedral to celebrate the homegoing service for our sister Mattie Hopkins. The Rev. Ed Rodman would say that Mattie Hopkins was the “Mother of the Union.” She was there from the beginning of the Union of Black Episcopalians with her quiet and insightful leadership skills. As a member of Trinity Church, she was active in her church, the diocese, and on the national church level, always moving the church to be what it should be and a forceful advocate for the Episcopal members of a darker hue. She often could be seen sporting African clothing and wore a short Afro hairstyle before many of our sisters were ready to make this statement of beauty.

The funeral service was grand in its Episcopal liturgical style. In the procession were several bishops as well as many clergy and lay leaders from the progressive side of the church. The addition of hymns from Lift Every Voice and Sing, the Episcopal African American hymnal, gave the service that Black church feel that Mattie would have appreciated. The casket sat on a platform that was covered with a beautiful piece of Kente cloth: bright reds, yellows, and oranges that stood in stark contrast to the traditional heavy pall of gold and white brocade that covered the casket. A statement was being made, one way or another; we just were not sure what it was.

The preacher said all the right things about the witness of Mattie to church and society. A few “amens” could be heard bouncing around the stone columns of the cathedral. The service moved forward in perfect order and, as it was coming to a close, we joined in singing “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” During the singing of what many call the Black national anthem, I realized what was wrong with the symbolism of the casket sitting “on” the Kente cloth. Something had to be done. Richard Tolliver, Ed Rodman, Earl Neal, and Jesse Anderson Jr., all priests, were seated with me to the left of the altar. I said to them, “Follow me,” and, to my surprise, they all did. As we approached the casket, I said, “Lift it up,” and they did. I pulled the Kente cloth out from under the casket and, in an act that would make traditional altar guild members faint, we covered the Episcopal white and gold brocade pall with the royal African cloth that a queen of Africa deserved. It truly was an act of the Holy Spirit.

What does it mean to be Black in the Episcopal Church?