Читать книгу Japan Style - Geeta Mehta - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеZen and the Art of Japanese Design

A surprising intellectual leap in housing design took place in Japan during the 14th century. This was an idea so powerful that it resonated for the next 600 years, and still retains enough influence in Japan as shown in the houses in this book. This intellectual leap sought to “eliminate the inessential,” and seek the beauty in unembellished humble things. It sought spaciousness in deliberately small spaces, and a feeling of eternity in fragile and temporary materials. A house’s interior was not to be just protected from nature, but to be integrated with nature in harmony. Influential Zen Buddhist priests in the Muromachi and Momoyama Periods articulated this ideal so well that leaders in many fields followed it, and the entire Japanese society aspired to it. What resulted were homes that speak to the soul and seem to hold time still. They provide a quiet simple base from which to deal with the world.

Around the time that European and English homes were becoming crammed with exotic bric-a-brac collected from the newly established colonies, Japanese Zen priests were sweeping away even the furniture from their homes. Out also went any overt decorations. What was left was a simple flexible space that could be used according to the needs of the hour. At night the bedrolls were taken from deep oshire cupboards, and during the day they were replaced, making space for meals, work, play and entertaining. This “lightness” was in part a response to Japan’s frequent earthquakes, and in part to the Buddhist teachings about the transient nature of all things. It is interesting to note that this ephemerality is not reflected in the architectural tradition in India, China or Korea, the three countries from where Buddhism arrived in Japan.

Wood is the preferred building material in Japan. The country’s Shinto roots have inculcated a deep understanding of and respect for nature. Japanese carpenters have perfected techniques of drawing out the intrinsic beauty of wood. Craftsmen often feel, smell and sometimes even taste wood before purchasing it. Although stone is available in abundance in mountainous Japan, it was traditionally used for the foundations of temples, castles and, to a limited extent, for homes and warehouses. Even brick buildings, when first built in Ginza around 1870, stayed untenanted for a long time, because people preferred to live in well ventilated wooden buildings.

Traditional Japanese builders designed houses from the inside out, the way modern architects professed to do until about two decades ago. A house’s exterior evolved from its plan, rather then being forced into pre-conceived symmetrical forms. Bruno Taut, a German architect trained at Bauhaus, and who came to Japan in 1933, claimed that “Japanese architecture has always been modern.” The Bauhaus mantras of “form follows function” and “less is more,” as well as the “modern” ideas of modular grids, prefabrication and standardization had long been part of Japanese building traditions.

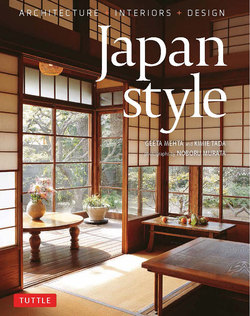

Minimalism and simplicity are the hallmarks of Zen-inspired traditional Japanese interiors. This effect is achieved by a rhythm of vertical and horizontal surfaces paired with natural colors. Exterior wall panels and shoji screens have been removed in this room to let the summer breeze and garden view in, making it “as open as a tent.”

Floor-plan of Zan Yu So—the organic organization of a Japanese house

Around the time when Leonardo da Vinci was developing a system of dimensions that scaled the human body for use in architecture, Japanese craftsmen standardized the dimensions of a tatami mat to 90 x 180 centimeters, which was considered adequate for a Japanese person to sleep on. Every dimension in a Japanese house relates to the module of a tatami mat. For example, the height of fusuma doors is usually 180 centimeters. The width of a structural post is usually one-tenth or one-fifth of 90 centimeters, and the post’s bevel is one-seventh or one-tenth of its width. Thus, as in da Vinci’s model, the proportions and scale of a traditional Japanese house can be considered to flow from the dimensions of the human body.

The houses shown in this book are a wonderful reminder that there are other alternatives to “big is beautiful,” and that eternity is not about permanent materials. Living in the “condensed” world—Japan’s population is half the size of the US, but it occupies a land area about 30 times smaller—the Japanese have developed a unique understanding of space. An ikebana arrangement charges the area in and around itself, and that space becomes an integral part of the design. The arrangement would not be nearly as effective without this empty space. One of the most famous buildings in Japan is the Taien tea hut built by Sen no Rikyu, the famous 16th century tea master. This masterpiece of Japanese architecture measures a mere one-and-three-quarters of a tatami mat, or approximately three square meters. This tiny house gives an example of how small houses do not have to take the form of the proverbial “rabbit hutches,” but can be beautiful and open like the Kamikozawa home (pages 178–183) and the house owned by Toru Baba and Keiko Asou (pages 98–107). After all, how much space does a man need?

The wood-floored engawa corridor mediates the relationship between the interior and exterior of a room. The storm shutters on the outer edge of the engawa are removed during the day so that the veranda becomes part of the garden, while at night, or during stormy weather, the shutters are closed to extend the interior space. These wooden storm shutters are a feature many newer houses in Japan do not have.

Traditional Japanese houses have a special relationship with nature. In extreme cases, the best part of a lot was given over to the garden, and the house designed on the land left over. Entire shoji walls can be pushed aside, creating an intimate unity with the garden. The engawa corridor modulates the relationship between the house’s interior and exterior. In summer, it belongs to the outdoors, while in winter and at night it is closed off to form part of the interior space as shown in the Zan Yu So villa (pages 20–37). As pointed out by architect Antonin Raymond, who came to Japan to work with Frank Lloyd Wright, “The Japanese house is surprisingly free. At night and in the winter, one can shut out the world and the interior becomes a box divided up into rooms. Then in the summer, one opens up all the storm doors, the sliding screens and sliding doors and the house becomes as free as a tent through which air gently passes.” Made of wood, mud and straw, the traditional house is also environmentally friendly and recyclable. Even old tatami mats can be shredded and composted.

The unassuming beauty of a minka farmhouse comes from natural materials such as unhewn logs, mud, bamboo and straw. Traditional building methods, perfected over hundreds of years, are employed to create a building that is ecologically sustainable and completely recyclable.

Simple interior surfaces and spaces add drama to the few objects d’art displayed in a room.

Another facet of the Japanese house, and indeed of Japanese life, is the dichotomy between the private and the public. In narrow but deep townhouses like Kondaya Genbei (pages 38–51), public dealings were confined to the house’s street side, while the rooms beyond were reserved for domestic life. The Japanese word for depth is oku, so a wife is referred to as oku-san, “the lady who inhabits a house’s depths.” How far into the home a guest penetrates depends on his relationship with the family. A house has a “public face,” which may or may not convey anything about the hidden interior. Powerful feudal lords often chose to live in the simple, understated Sukiya-style spaces, while visitors would only see the ornate staterooms. However, the private areas allowed for little privacy, since mere paper screens or thin walls separated the rooms from each other. This fact has probably contributed to the deeply ingrained sociable manners in Japanese people, especially women.

This large country house and its garden are seen here through the perimeter fence. Built with natural materials and colors, the house nestles comfortably in the garden that attempts to mimic the great outdoors as closely as possible. The ethos is of co-existence with nature, not control over it.

Types of Japanese Houses and Interiors

This book focuses on several types of houses and interiors. Yamamoto’s minka (pages 108–119) is a good example of Japan’s rustic farmhouses, which were functional and built of sturdy local materials. Such a house can be generally divided into two distinct zones. The entrance area (about one-third of the space) is called a doma, and has a packed earthen floor. A family would cook, produce crafts and in very cold climates, also tether farm animals here at night. The farmhouse’s second zone usually stands on a wooden plinth and includes the living area and bedrooms. The large hearth at the heart of the main room was the hub of family activity in such homes, the beauty of which is derived from rustic materials such as unhewn timbers and from the integrity of ancient building techniques. The heavy roof with deep eaves on these farmhouses, which often constitutes two-thirds of the elevation, makes them appear comfortably rooted in their surroundings. Frank Lloyd Wright considered the minka an appropriate symbol of domestic stability, and they became one of the several Japanese ideas that influenced his residential designs.

Most of the houses in this book were built in an urban context. The larger homes, such as the Tsai house (pages 120–131), are located in the countryside, but have a strong emphasis on formality, and are built in the Shoin or Sukiya–Shoin style like their urban counterparts. Elements of these houses have evolved from the rigid Shinden style that was borrowed and adapted from China during the eighth century. This style consisted of a central chamber reserved for the master of the house, with corridors, smaller rooms for the family and pavilions that flanked this room, all arranged around a small pond or a garden. During the Muromachi Period (1336–1572), the Shinden style evolved into the Japanese Shoin style, used for the reception rooms of the aristocracy and the samurai classes, but which was banned in the homes of common people during the Edo Period (1600–1867). This style includes four distinct elements that have been formalized over time: the decorative alcove (tokonoma) for hanging scrolls and other objects; staggered shelves (chigaidana) located next the tokonoma; decorative doors known as chodaigamae; and a built-in desk (tsuke shoin) that usually juts out into the engawa, flanked by shoiji paper screens. All these features started out as pieces of loose furniture, but were built in over time, in keeping with the Japanese preference for clean, uninterrupted spaces. Tatami mats usually cover the entire floor in these formal rooms.

As the tea ceremony increased in popularity during the Muromachi, Momoyama and Edo Periods, the ideal of the humble tea hut began to exercise a strong influence on Japanese housing design. Ostentatious Shoin-style interiors gave way to the more relaxed Sukiya–Shoin style in all but the most formal residences. Sukiya style turned all the rules of the rigid Shoin style inside out, and provided abundant opportunities for personal expression. It sought beauty in the passage of time, as seen in the decay of delicate natural materials in an interior and the growth of moss on tree trunks and stones in a garden. While the rest of the world searched for the most durable and ornate building materials, Japan’s elite were scouring their forests for fragile-looking pieces of wood that would underscore the imperfection of things. The moth-eaten wood selected by Baizan Nakamura for his cabinet doors (pages 172–173) is an example of this trend. The ideal of wabi-sabi, translated loosely by Frank Lloyd Wright as “rusticity and simplicity that borders on loneliness,” was considered the epitome of sophistication. For interiors, Sukiya style also favored asymmetrical arrangements, while avoiding repetition and symmetry. Posts on walls were arranged so as not to divide a wall space into equal parts. A variety of woods were used for different parts of the same structure to add interest. However, such diversity results in a satisfying whole because of the discipline of horizontal and vertical lines and muted soft colors. The goal is to please rather than impress the visitor. The owners of such houses participated in the selection of materials and the playful details such as doorknobs and nail covers.

These small tea ceremony utensils underscore the attention to detail in Japanese design. At left are two whisks referred to as chasen; one has been turned over on a stand especially designed for that purpose. The flat scoop (chashaku), is an object of art in its own right. During the Momoyama and Edo Periods, men of power often vied with each other in crafting this simple object.

Japanese and modern Western elements of this interior complement each other, since both aspire to the beauty of simplicity. The shoji wall on the left is completely removable.

The focus on Japanese design is not on surfaces, but on the quality of the resulting space. This modern Japanese house achieves the feeling of traditional Japanese space with modern materials and furniture.

Sukiya–Shoin rooms are often complemented by tea huts in their gardens. It was not unusual for architects and designers to make full-scale paper models (okoshiezu) of a tea hut to perfect its designs before the actual construction process began.

Five of the houses in this book were not built with traditional materials and techniques, but have nonetheless been included because they express the dynamics of Japanese space and sensibilities. Although traditional houses are decreasing in number, traditional spatial concepts inform the work of many contemporary architects in Japan. While most Japanese now live in apartments or modern homes that are usually small but comfortable, they maintain deep pride and love for their traditional architecture. With growing awareness of the many wonderful buildings already lost to the recent development frenzy, there is now renewed interest in saving traditional structures. Several homes in this book were moved to new locations for preservation—a very encouraging sign. I hope that this book will strengthen this trend.

The houses featured in this book are important not just for the Japanese but also for all of us. They invite us to rethink the wisdom of our unsustainable lifestyles. Contrary to Le Corbusier’s adage of modern architecture, a traditional Japanese house is not simply a “machine to live in,” but a home for the soul.

Furniture—such as this display alcove, shelves and cupboards—are built into the room to achieve unobstructed space. The bold dark lines of the wood frames and tatami mat borders work with vertical and horizontal planes to create an intensely calm effect.