Читать книгу Japan Style - Geeta Mehta - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

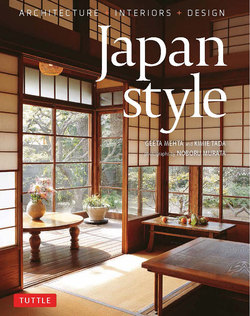

ОглавлениеElegant Style in a Kyoto Machiya

Located in the heart of Kyoto, the Imperial capital of Japan for over 400 years, Kondaya Genbei is an excellent example of an elegant Kyoto-style machiya, or merchant’s townhouse. Muromachi, the district where this townhouse is located, was once a powerful trade center known for its aristocratic tastes and many elegant buildings. Kondaya Genbei was established in the 1730s and has since served as a residence and a shop where traditional kimonos and obi sashes are crafted and sold. The prosperous business is presently run by the tenth generation owner, Genbei Yamaguchi, who is also a kimono designer himself. In 2002, he helped revive a species of silk cocoons called koishimaru. These cocoons was used in ancient Japan for making a delicate variety of silk capable of taking on vivid dyes, but had been replaced with larger cocoons because they were too small for the efficient production of silk. Due to Genbei Yamaguchi’s efforts, silk of this sort is in production again after a hiatus of many decades.

This two-story timber building sits on a deep rectangular lot along the street, with a 30-meter façade several times larger than the neighboring lots. Narrow frontages are typical of machiya since the properties were taxed based upon the width of their street fronts. The outside of the house is made up of wooden lattice painted with Bengala, a reddish colcothar so named because it was first imported from Bengal in India. The entrance leads into a doma, a room with an earthen floor, used for casual meetings or the receiving of supplies. One does not need to take shoes off here. Rooms beyond this one are raised on a wooden plinth and get more sophisticated and private along the tori-niwa corridor leading into the house. The inner part of the house also contains a small garden (tsubo-niwa), a tearoom (cha-shitsu) and two storerooms (kura). The tsubo-niwa helps ventilate the interior, while bringing nature in. The storerooms, set apart from the main house, are protected by heavy, fire-resistant plaster walls. Merchandise and family treasures are stored in them to this very day.

In Japanese culture, food, clothing as well as décor reflect the changing seasons. Kyotoites have traditionally delighted in changing the décor of their homes to create an ambience of coolness during the warm summers. The Yamaguchis observe this vanishing custom by removing the shoji and fusuma paper screens of their home, replacing them with woven wooden frames (sudo) draped with beautifully woven bamboo blinds (sudare). The open weave of the sudo blurs the division between interior and exterior, allowing residents to look out, while letting light and breeze in. Through these screens, the rays of the summer sun appear soft as twilight, and the moiré-like pattern cast by overlapping sudo reminds one of a cool rippling pond. A closely woven rattan rug made from Indonesian cane (tou-ajir) is laid over tatami mats, and the dark sheen it acquires over time is associated with a perception of coolness. Summer in Kyoto also heralds the coming of the famous Gion Festival—which dates back to 869 AD—and the Yamaguchis continue the tradition of old families who displayed special heirlooms such as byobu, armor and kimonos that are in the theme of this festival in their home during this time of the year.

Tearooms are made intentionally small and plain, so as not to distract from the important goal of achieving harmony within oneself. This tearoom is of four-and-a-half tatami mats, a popular size that refers to the hojo—the quarters of Zen abbots—so named after the humble hut of a sage in India that Buddha is said to have visited. The tea garden can be seen through the sudo screens on the window.

Before approaching the tearoom, guests make a ritual stop at the water basin in a tea garden to wash their hands and purify their spirit.

In summer, an ice column placed on a wooden veranda (engawa) provides natural air-conditioning as well as a treat for the eyes. The Yamaguchis replace teacups and pots made of ceramics with glass ones during the summer, placing them on coasters made of reeds. The rattan rug laid on the tatami mats has a wattle pattern, which enhances the suggestion of coolness. The shoji screens have also been replaced by openwork sudare blinds. The basket has a flat paper fan (uchiwa) with a design of kabuki make-up.

The walk along the dewy path (roji) is occasionally interrupted at a turn by an odd stone (tobi ishi), which forces one to look down to ensure balance. Then the refreshed eyes look up to see a special accent such a stone lantern (toro). The moss and bushes are tended every day to keep the garden looking fresh. This, like the freshly watered roji, is a sign of welcome for the guests.

During the Gion Festival, which runs the entire month of July, old families follow the tradition of inviting guests to their formal room where folding screens (byobu), kimono and armors are displayed. This pair of six-paneled early 18th century screens with hawks was painted by Tsunenobu Kano of the famous Kano school. The flower arrangement in the bamboo container gently demarcates the area accessible to guests.

A sculpture depicting eggplant fruit and flowers sits on the writing desk (tsuke shoin), while light streams in from sudo screens.

The ears of rice and sakaki leaves in the alcove (tokonoma) form a display reflecting the ritual decoration of floats paraded in the Gion Festival. Koishimaru are placed on a small offering stand (sanbo) made of wood.

This tatami room opens onto the earthen-floored corridor leading to the entrance porch. Seasonal flowers are laid out in preparation for ikebana. The fusuma paper has a design of orchid flowers, block-printed by hand using iridescent mica paint.