Читать книгу Japan Style - Geeta Mehta - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеA Tea Master’s Home in Aichi

Sado or the “Way of Tea” seeks to extend the meditative simplicity of the tea ceremony or chanoyu into all aspects of life. The ideal of a mind in complete harmony with nature and free from the turmoil of worldly affairs has blossomed in Japan since Zen Buddhism arrived here from India and China in the 13th century. From the Meiji Era (1868–1912) to the early Showa Period (1926–1989), many influential people in political and financial circles became particularly strong proponents of chanoyu, as they searched for balance in their secular and spiritual lives. This helped the ideals of chanoyu strongly influence many arts in Japan including architecture, painting, pottery, poetry, calligraphy and flower arrangement. In architecture, chanoyu has generated a special style called the Sukiya style, known for its minimalism, simplicity, rusticity, understatement and a restrained playfulness. The Takamatsu house was built in 1917 in the Sukiya style by Teiichi Takamatsu, a renowned votary of chanoyu in Nagoya district, located between Tokyo and Kyoto. The second-generation head of a wealthy family that owns substantial real estate, he brought his profound love of chanoyu to the building of his house. After his son inherited the family business and his father’s beloved residence, this house became the setting for many dramas in the financial scene of Japan for the next several decades.

This historic legacy nearly came to an end when the house was slated for destruction in 1985. Fortunately, Teruyuki Yamazaki, a businessman with a deep understanding of Japanese architecture, helped save this invaluable Sukiya-style house by purchasing it as a guest house for his company. The new owner was moved by the fact that the Takamatsu house was nearly as old as his machine tool exporting company, Yamazaki Mazak Corp., which was founded in 1919, and had witnessed the same historic developments.

Yamazaki relocated the Takamatsu house—which was relatively easy to do, since traditional Japanese homes are made of skillful wood joinery—to a scenic part of the Aichi Prefecture on a generous 6,700 square meter plot with a good view of the Kiso River. It has now been renamed Zan Yu So, which literally means, “a villa to enjoy oneself for a while.” The rebuilding of the Takamatsu house was completed in 1990 after five years of reconstruction, involving just a few changes necessitated due to its move. Besides the grand reception room of this house, which has 20 tatami mats, there are several ten-mat rooms, each one with a different theme and an elaborate interior. All the rooms offer picture-perfect views of the lovely garden, which also has a special tearoom connected to the house via a passage. In keeping with the true Sukiya aesthetics of understatement, this large house has an air of modest elegance rather than showy pride. Its natural simplicity and a sense of stillness are still spiritually uplifting, in keeping with what the original owner might have intended.

A cupboard for storing shoes is an essential feature of a genkan, the entrance for welcoming guests. The sliding doors here are covered with paper with the special pattern usually reserved for larger sliding doors called fusuma.

Slippers await guests in the genkan of Zan Yu So. Changing from shoes worn outside the house to slippers is symbolic of getting into a more relaxed state of mind. The quiet lines and understated material of this new entrance have been carefully designed to harmonize with the old reconstructed house.

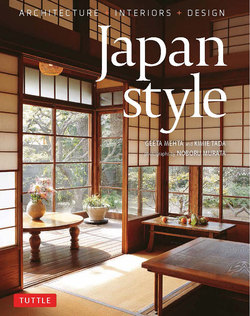

The relationship between the interior and the garden is very important in Japanese architecture. The gardens are designed to be viewed from the low vantage point of a person seated in the room on a tatami mat. Here the shoji screens have been slid aside to open the drawing room to the beautiful garden. The roofed gate (naka-kuguri) and the tearoom are visible on the right of a grand Japanese oak tree. The panel on top of the shoji screens (ranma) is known as muso mado—one perforated panel slides behind the other, opening or closing the apertures to suit the different ventilation needs of changing seasons.

The grand reception room, Kairaku-no-ma, is decorated in Shoin style. This interior design style was originally named after the built-in writing desks (tsuke shoin) in the rooms of Zen priests. Since then, a built-in desk and the accompanying shoji window have become ceremonial elements of formal décor, as seen in this room. The deep tokonoma, another element of the formal Shoin style, holds a cha-ire—a pot for preserving green tea—that had been a gift from Tsunayoshi, the fourth Tokugawa Shogun, to one of his vassals. The hanging kakejiku was painted by Tanyu Kano (1602–1674), a renowned painter of the Kano school, which supplied the Shoguns with their official painters for as long as 300 years.

An arrangement of open shelves (tsuri-dana) and low storage compartments (ji-bukuro) in the recess adjoining the tokonoma is part of the traditional Shoin-style décor.

The small stand and the writing case (suzuri-bako) is beautifully decorated by exquisite artwork known as maki-e. In this technique, a design with lacquer and fine specks of gold and silver is painted in several layers on a prepared wooden surface.

The tokonoma alcove in a tearoom named Zanyu is decorated by a hanging scroll (kakejiku) with five Chinese characters which represent prosperity. On the left of the tokonoma is the “sleeve wall” that separates the tearoom from the host’s entrance. The post at the end of this half wall is called nakabashira, or the central pillar, and this as well as the corner post in the tokonoma alcove (toko-bashira) is selected with great care as they set the aesthetic mood of the tearoom.

The square entrance to the tearoom, called nijiri guchi, is made very small, just 60 centimeters high in this case. The traditional reason for making the guests enter the tearoom on their hands and knees was to make them leave their swords and egos behind, coming in with a humble and pure mind. The soft outline of shitaji mado, the bamboo and reed lattice is seen through the shoji screen. Japanese paper (washi) is pasted to the lower portion of the walls (koshibari) to protect the guest’s kimonos from the mud plaster on the walls.

This mizuya with a cupboard for tea utensils and a sink in which to wash them adjoins a formal area. Every little detail is thought through and made as beautiful as possible. The floor-level sink covered with a bamboo mat is one example of this attention to detail.

Utensils used in the tea ceremony are made of bamboo. At left are the whisks (chasen), used to briskly stir the green tea (matcha) in the teacup with the hot water. The flat scoop, called chashaku, is used to measure the powdered green tea into the tea bowl. The flat toothpicks (kuromoji) are used by guests to eat Japanese sweets during a tea ceremony. The guests often bring their own kuromoji, along with Japanese paper napkins, in a special bag tucked inside the collar of their kimonos when they arrive for the tea ceremony.

A humble hook is provided on a post in the small kitchen (mizuya) for hanging the tea cloth.

A path of stepping-stones, also called “dewy path” or roji, leading to the tea hut is seen here through the glass window. A simple gate (nakakuguri) in the middle of the garden separates the inner and outer tea garden. Passing through the middle gate is symbolic of entering the tea world. Moss is a prized element of a tea garden and is carefully cultivated.

The veranda (engawa) modulates the area between the inner and outer zones, allowing sunlight into the house and protecting it from rain. In summer it forms part of the garden; in the winter the engawa can be closed off to form an extension of the interior space.

The toko-bashira, or the main post between the tokonoma and chigaidana, is made of northern Japanese magnolia wood, and has been selected for its artistic effect. The ceiling made from a variety of woods, paper and reeds adds an air of rustic elegance to this anteroom.

The large panel in this tokonoma (toko-ita) measures 360 centimeters across and is made from a single piece of very rare pinewood.

The door pulls (hikite) — depicting a pigeon (top), a peacock (middle) and a boat oar (bottom)—are selected to suit the theme of the room. The peacock hikite is fashioned from lacquer and real gold.

The alcove in a room named Takatori-no-ma has a fine post (toko-bashira) made of kitayama-sugi, a very high-quality wood. The wall on the side of the alcove has a window with a graceful bamboo lattice in an unusual diagonal pattern.

Rooms designed in a manner less formal than the Shoin style are referred to as hira-shoin rooms. The lower part of this hira-shoin has a sliding slat window (muso mado). The checkered openings on the front and back slats can be lined up to allow for air circulation.

A small wooden case (suzuri-bako) holds an ink stone, an ink stick, a brush and a tiny water bottle used for mixing ink.