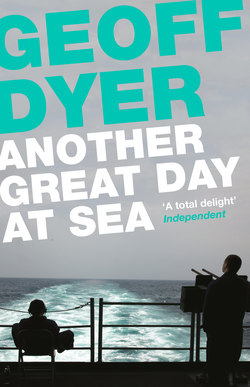

Читать книгу Another Great Day at Sea - Geoff Dyer - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5

Breakfast in the Ward Room was a fried reek of congealed eggs, bacon and other horrors avoided—if not ignored—in favour of cereals, tinned fruit and yoghurt. After that we went right to the source, to the kitchens where it had all been prepared. Showing us round was Warrant Officer Charles Jakes from New York City. He was African American, and had spent twenty-five of his forty-four years in the Navy. In a way that I was becoming accustomed to Charles ran—as opposed to walked or strolled—through a description of his mission and his routines. He was in charge of 112 cooks and 180 food attendants, serving seven places to eat on ship. Increasing quantities of the stuff served in these venues were pre-prepared rather than cooked from scratch (which saved money and time, cut down on staff and accounted, in part, for why meals on the boat were less than appetizing).

The idea, Charles explained, was to go forty-five days without running out of anything. And twenty days without running out of fruit and veg. He took us into a freezer—the size of a Manhattan apartment—and talked us through its contents. Eight thousand pounds of chicken, five thousand pounds of steak, four thousand pounds of hamburger. Waiters in American restaurants always employ the first person singular when announcing and describing the day’s specials. ‘I have a lamb casserole with a radish reduction,’ they will say, as though this interesting-sounding confection has been summoned into existence by his or her descriptive efforts alone. In Charles’s case this grammatical habit took on gargantuan proportions.

‘I aim to eat my way through everything on the boat,’ he said. ‘So, going back to the US, I got a million dollars or less left for the last forty-five days.’ It made Paul Newman’s boast in Cool Hand Luke—‘I can eat fifty eggs’—seem pitiful, the equivalent of ordering a single softly boiled egg on toast. Speaking of eggs, we moved from freezer to fridge to gaze at 230 boxes of them, which made a total of 575 dozen eggs. This looked like a lot but I calculated that it added up to only just over one egg per person; hence Charles’s eagerness to offer reassurance. ‘These are not the only eggs. Most the eggs are frozen. These here are just back-up.’ Good to know.

En route to one of the store rooms, we passed another chill box which was actually the morgue. ‘Ain’t nobody in there at the moment,’ he said. ‘And if there was there’d be a guard outside.’ That was good to know too.

As we entered the store room Charles warned that it was in a seriously depleted condition. At the beginning of the deployment stuff would have been piled so high we would not be able to see over the stacks. Now, near the end of deployment which, he hoped, would clean the place out, they were rarely more than four feet high.

First thing we saw was a low-level expanse of popcorn (‘they just love popcorn round here’). Beyond the popcorn were six-pound tins (like big pots of paint) of Country Sausage Gravy, Great Northern Beans, Victory Garden Pork and Beans, Popeye Leaf Spinach, Heinz Dill Kosher Sandwich Slices . . .

Like a mother whose son has turned up unexpectedly Charles kept stressing that levels were this low because we only had forty-five days at sea left, that, relatively speaking, there was almost nothing to eat.

Before moving into the bakery we donned little paper Nehru hats. The bakers, from New York, Texas, Chicago and California, were lined up to meet us. They bake eight thousand cakes a week, not counting the ones made for special ceremonies in port (epic cakes iced in the colours of the American flag and the flag of the host country). Our visit was not ceremonial exactly but they had prepared some samples for us. I love cake, cake is my popcorn, and I was glad to be able to tuck in as though it were the snapper, not me, who was always picking at his food like some high-achieving anorexic. It was incredibly hot in here—hot, as Philip Larkin remarked in a different context, as a bakery.

‘You’re not troubled by the heat in here?’ I said.

‘Uh-uh,’ said one of the bakers. ‘Sometimes it gets pretty hot.’

‘This is not hot?’

‘This a really cool day.’

The visit was as near as I was ever likely to come to being a touring politician or a member of the royal family. I actually found I’d adopted the physical stance of the monarch-in-the-age-of-democracy (standing with my hands behind my back) and the corresponding mental infirmity: nodding my head as though this brief exchange of pleasantries was just about the most demanding form of communication imaginable.

From the bakery we moved into one of the real kitchens: the heart (attack) of the whole feeding operation where Charles resumed his narrative of singular endeavour: ‘I aim to prepare maybe four thousand . . . ’, ‘When I’ve eaten twenty-five hundred pounds of . . . ’ I’d got it into my head that this was not just a figure of speech, and now found it impossible to shake off the image of the genial and willing Charles scarfing his way through piles of meat, potatoes and vegetables, gorging his body beyond its performance envelope, a Sisyphus scrambling up a mountain of food, a calorie-intensive reincarnation of the Ancient Mariner. In its way it was a far more impressive feat of solo perseverance than even the pilots could achieve.

All around were boiling vats as round and deep as kettle drums. A lot of meat was being prepared, plastic bags stuffed full of barbecue chopped pork.

‘Hmm, smells good,’ I said, instinctively remembering that nine times out of ten the most charming thing to say in any given situation will be the exact opposite of what one really feels. The truth was that the smell was a sustained and nauseated appeal on behalf of the Meat-Is-Murder Coalition or the Transnational Vegan Alliance. But what can you expect when you’re in the middle of the ocean with five thousand hungry bellies to stuff, most of them needing plenty of calories to fuel their workouts at the gym?

Our tour concluded with a look at another store room. Notwithstanding Charles’s warning about the paucity of supplies, the acute lack of any sense of shortage gave rise to a form of mental indigestion. It was reassuring looking at these tins, seeing them stacked, knowing one would not—I would not—be sampling their contents. But what a disappointment if the carrier sank and treasure hunters of the future discovered not the sunken gold and jewels of galleons from the days of the Spanish Armada but thousands of cans of gravy and kosher sandwich slices: the lost city of Atlantis re-imagined as a cut-price hypermarket that had slipped beneath the waves.