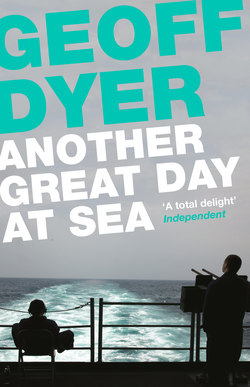

Читать книгу Another Great Day at Sea - Geoff Dyer - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление9

When we eventually got to the chapel we were shown around by Commander Cameron Fish—Fish the Bish as he was known during a stint with the Royal Navy. In his late forties, I guessed. He had a narrow face, narrow as the prow of a long boat, but he was at pains to emphasize the breadth of religious belief on the boat. The chapel was there in accordance with constitutional guarantees of religious freedom, not because they were evangelical, he said, sounding more than a little evangelical. Accordingly the chapel changed function—changed religion—depending on who needed it and for what at any given time. The numbers attending were broadly in line with the churchgoing population of the United States—if an adjustment was made for the fact that a disproportionate part of the ship’s population was from the Christian heartland of the South and the Midwest. There were, the Bish thought, maybe twelve sailors on board who were Jewish by religion, fifteen or twenty Muslims and eight Buddhists, but right now the chapel was being readied for the Pentecostal Bible study class.

The Bish asked Curtis Bell, who was leading the class, if we could stick around. Curtis was wearing a digital camouflage uniform and large spectacles (specially designed, it seemed, for close study of books with many words in very small print). The extreme gentleness of his manner stood in sharp contrast to his heavy, perfectly shined boots. I suspect his impulse, understandably, was to not have us there, but he wrestled quickly with his conscience and, with great courtesy, didn’t simply agree to let us stay but invited us to do so.

There were only seven people in attendance but that’s enough, once the singing starts, to constitute a congregation and choir. One of the women led the singing, setting up the call—‘Glory to his name’—joining in the response and moving on to the next call: ‘Down at the cross’. I love gospel, especially like this, with no instruments, just uplifted American voices and loose rhythmic hand clapping. To be honest, within thirty seconds the atheist’s spirit was moved, tears were trickling down his unbelieving cheeks. Christianity! American Christianity! African American Christianity! The choir of voices, the chain of hands clapping, the promise of freedom and the history of acceptance, resilience and resistance—of breaking the chains—that is there in every line. Oh, I could feel the happiness of it, the joy of being ‘wondrously saved from sin’ even though the whole idea of sin—and, consequently, being saved from it—was complete nonsense. But it really was a lovely hymn and when it ended I could feel the whole hallelujah-ness of it in myself and the warmth that comes from being in the presence of good people.

Having brought the singing to a close the sister whose name I did not catch moved on to the next phase of the evening.

‘I give you all the Glory, all the Honour, all the Praise. Thank you. Thank you for your Holy Spirit. Thank you for sending down your Son to die on the cross.’ Thank you for this and thank you for that, thank you for everything, and a special thank you—this was me, extrapolating—for the suffering that gives us the opportunity to thank you for the possibility of bringing our suffering to an end. It was a massively extended and spiritual version of impeccable manners.

‘Alright! We are in for a treat tonight. Amen. We’re gettin’ this man full of fire. He’s gonna come down and give you what thus sayeth the Lord. He’s gonna take you up on each scripture. He’s gonna break it down so that you know exactly what this scripture meant. He’s not one that takes scriptures out of context. He’s gonna make you understand so you’re like in kindergarten. Make it plain as day. Amen. He’s a true man of God. He follows the spirit, he leads by the spirit. He does everything in decency and orderly. Everything is all of one accord. Amen. I give you none other than brother Curtis Bell.’

Before brother Curtis could take the stand there was another round of singing. It only a took a line—‘There is power in the precious blood of the lamb’—and there I was, back in it again, in the small tide of voices ebbing and flowing, calling and calling back.

‘Pow-er . . . ’

‘Power Lord!’

‘Power . . . ’

‘Power Lord!’

Lovely though it was, the singing had to come to an end so that we could get on with the Bible study part of the evening. Curtis needed a whiteboard and brother Nate was sent to get one. A sister read out a passage of Romans chapter 10, verse 9. ‘That if thou shalt confess with thy mouth the Lord Jesus, and shalt believe in thine heart that God hath raised him from the dead, thou shalt be saved.’

To understand this in context, Curtis explained, you had to bear in mind what had come before. For example: ‘For they being ignorant of God’s righteousness, and going about to establish their own righteousness, have not submitted themselves unto the righteousness of God.’

There followed a confusing exegesis, accompanied by Curtis writing the essentials on the whiteboard: ‘Righteousness = justified = redemption = salvation = saved.’

It was a terrible shame. The singing had been so wonderful but now the evening had descended into low-level lit crit of a text that didn’t merit any kind of serious scrutiny. It was no better than an aged mullah reducing the complexities of the world to something that could be resolved by a close study of the Qur’an. Curtis was a righteous, spiritual, decent man—he was all the things he had been described as being: a fine man, but he had pledged his light to darkness, had chosen ignorance rather than knowledge and all his knowledge was no more than the elaboration of ignorance. The gap between that and the singing, so heartfelt and full of the spirit, was huge even though the two shared a similar inspiration and belief.

I caught the snapper’s eye. We snuck out.