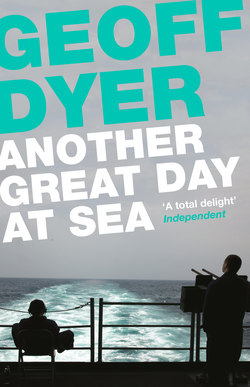

Читать книгу Another Great Day at Sea - Geoff Dyer - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление8

Travellers to Thailand will be familiar with the way that when the national anthem comes on the radio everyone stops whatever it is they’re doing—issuing you with a ticket for a train that departs from Chiang Mai for Bangkok in two minutes—and listens. It was the same here with the Captain’s daily address to the ship’s company. We were in a walkway—of course we were in a walkway, we were always in a walkway—on our way to the chapel, but froze, mid-stride, as the Captain reminded everyone that it was ‘a great day to be at sea’. I suppose it was, given the sun, clear skies and the lack of typhoons and incoming torpedoes. What I didn’t realize was that the Captain always told everyone what a great day it was. Despite this, he always managed to re-italicize or re-emphasize the ‘great’, as though yesterday had not been quite as great, and today, while in many ways indistinguishable from the interminable days that had gone before, was somehow better and greater, thereby raising the possibility that tomorrow might be even greater. It became a standing joke among the crew, and I wondered what would happen when they were making their way back across the Atlantic in November, in Force 9 gales and twenty-foot waves: would he manage to maintain their belief in something they already regarded with a degree of affectionate irony? For now, they expected and looked forward to these daily affirmations of greatness, would have been sorely disillusioned, possibly even mutinous, if he’d summed up the day as merely ‘tolerable’, ‘OK’ or ‘fine’. There was something very American about this ability to dwell constantly in the realm of the improvable superlative.

The next part of his speech was devoted to publicizing the achievements of the Avenger of the Day, a member of the crew who had been selected for his or her outstanding work irrespective of what that work happened to be.

After this it was down to emailed suggestions from the crew about how things could be improved, how the great days at sea could be made greater. On the one hand, this was a way of turning gripes into suggestions for problem solving: the toilets (the heads) employed a new vacuum system that was prone to blocking and so, at any one time, a number of lavatories seemed to be out of action. This, evidently, was an ongoing source of grievance, one that the Captain was always having to address. On the other hand it was part of the larger ethos of individual and collective improvement that pervaded the ship. I was always seeing little notices exhorting the ship’s company to do better. Sometimes these would take the form of generalized encouragement: ‘STOP looking at where you have been and START looking at where you can be!’ Other times they would encourage the traditional pride of a given department or division—‘Setting the standard for excellence’—which bled, naturally, into rivalry. Among the various squadrons of the air wing there were constant and competing reminders and claims to be ‘The Tip of the Spear—Stay Sharp’. The Spartan (Helicopter) Squadron’s ‘Command Philosophy’ was broken down into increments:

Take The Fight To The Enemy And Win

Bridge The Gap Between Good And Great

There Is Great Honor In Service To Country

Everyone Is Important

Be Meticulous Stewards Of The Assets We Employ

I loved these and the many other reminders to do better, to improve, but my favourite was somewhat uncertain in intention and effect: ‘It’s not broke you’re just using it wrong.’

Being English, having grown up in a land of out-of-service payphones and faulty trains, my immediate response to this was ‘But what if it is broken?’ What I really liked, though, was the way that the message demonstrated and reflected its own irrefutable truth: that the language, while broke (as opposed to broken), still functioned in spite of being used wrong (incorrectly).