Читать книгу The Wonder Singer - George Rabasa - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

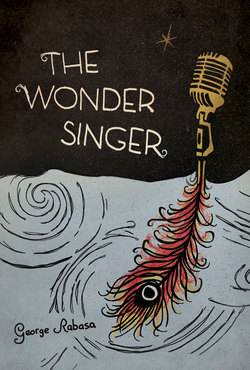

ОглавлениеTHE WONDER SINGER: MY STORY

BY MERCÈ CASALS AS TOLD TO MARK LOCKWOOD

The Girl in the Trees

Every hour that my father did not return to the inn was spent in a fog. I would be awake for hours, eager for the sound of his voice, his heavy steps on the stairs. During the day, I would avoid the other guests by sleeping. I dared not face what was happening. I didn’t like the pitying looks people gave me. However, I was cared for. There was hot food for me, and a cot in a quiet corner, even though I had to give up the room my father was no longer paying for.

By the third day, I was aware of impatient looks, muttered questions: Did I have any relatives I could go to? Clearly the innkeeper was not looking to adopt an orphan. While I was having my café con leche and bread for breakfast, the innkeeper’s wife packed my clothes and placed my suitcase by the front door. I realized I was leaving, though I did not know where I would go, or with whom. By midmorning, Pep Saval was leading me out the door and onto the road. Not understanding what was happening, I dragged my feet and kept falling behind.

“Are you scared of me?” He stopped several meters away from the inn and challenged me in a tone more gruff than I believe he intended.

“Do you know why my father has gone?” I asked at last.

“No, my sweet. Disappearing is the last thing I expected from him.”

“He owed you money.”

“It was only a game to pass the time. I wasn’t going to drive your father into poverty.”

“So you won me instead.”

“Only a few songs.”

“You’ve been cheated. My voice does not belong to my father.” I paused a moment. “Are you angry at me for saying that?”

“No, it makes me glad.”

Moving down the road, following the contour of the dusty, wilting vineyards toward the open country, Pep Saval kept trying to persuade me that I was to feel safe in his company. I finally mumbled assent to stop him from going on and on.

We walked for the better part of the day. We established a contest of wills; he would not tell me where we were going. I wouldn’t ask. As long as he was willing to carry both our bags, I was content to follow. We walked through an occasional village, but rested only briefly to drink at the town well.

He finally suggested we stop to eat under the shadowy foliage of an oak. I sat on a flat rock and watched while he cut a tomato in half and rubbed its pulp onto the crusty bread with a generous drizzle of olive oil. Pa amb tomàquet.

“It needs salt,” I complained after taking a tentative nibble.

“Really?” He frowned, trying not to act pleased. “I think the bread is salty enough. Too much salt hides the taste of this perfect tomato, sublime if you compare it to its flavor yesterday and how it would have tasted tomorrow. We must eat it at this very hour, at the peak of its existence.”

“Didn’t you bring any salt?” I insisted.

Pep Saval sighed. Of course he carried salt. He opened a packet and took some grains to sprinkle over the bread.

After eating, Pep Saval leaned against the tree trunk, pulled his beret down over his eyes and, lacing his fingers over his belly with a long, happy groan, drifted off to sleep. I was free to leave, but he knew I had nowhere to go.

When he awoke after half an hour, he realized that I was no longer sitting under the oak. He walked around the tree as if circling a reluctant dancing partner. He uttered a simple prayer, his eyes gazing toward the sky, then sighed with relief when his prayer was answered: I couldn’t prevent the creaking of the branches when I shifted my weight, followed by my stifled laugh.

“Come down,” he called up. There was a slight stirring as I found a high perch in the V formed by two limbs.

“I’m right by a nest!” I called back.

“If you disturb the eggs you’ll get pecked by the mother bird.”

“I’m just looking at them.”

“I could tell you about the time I saved three baby robins,” he boasted. “Only I’m tired of shouting and not seeing your face.”

“Start the story,” I pressed. “If I like it, I’ll come down.”

“Nena, come down,” he pleaded. “It’s not the kind of story one tells by shouting.”

“If you keep calling me ‘child,’ I will never again do anything you want me to do.”

“If you don’t stop acting like a child, I’ll never ask you to do anything. I won’t tell you to eat or sleep or bathe. You’ll be free to be the little savage you obviously enjoy being. A monkey that enjoys hanging from trees.”

I scrambled down to a lower limb, but remained concealed by the thick foliage. “You don’t have to shout now.”

Taking a deep breath, he leaned back against the tree’s wide trunk and began softly, “When I was a boy, just outside the town of Sant Quirze the woods were thick with oak. There was one tree that was the king of all the trees. It was older and taller and its gnarled branches spread out wider than any of the others in the forest. We called it Old Father Tree. When we wanted the highest vantage point in the region, that was the tree we climbed.”

“Can’t you speak louder?”

“I used to spend the hot summer afternoons within the shade of Old Father Tree. It was the place where I felt the safest.”

“I thought you were going to tell the story of the robins.” I had climbed down to a branch just above his head.

“This love of heights was true of the birds, too. Since the children of the village loved to hunt them down with sling shots, it was only in the depths of Old Father Tree that a bird was safe.”

“Is that where you discovered the nest with the robins’ eggs?”

“I looked down on the nest that was secured just below the branch where I was sitting. The eggs were like jewels,” he said, hardly above a whisper. “The most elusive color of blue. Blue like lilacs at the time of their blooming, blue like some girls’ eyes when the light strikes them just right, or blue like a certain star that appears sometimes in the midwinter sky. I hardly dared breathe for fear of disturbing them. And they were so lonely. I thought I had scared their mother away. By six o’ clock a wind that smelled of rain started to blow, and fat, cool drops were falling down on us. At first it was dry within the foliage, but as the leaves began to drip, the nest got wet.

“I laid my felt cap over the eggs to protect them and went home. I thought about those eggs all through the storm. In my thoughts I kept blowing my breath on them and hoping the mother robin would return finally and lift the edge of the cap like a blanket to reveal her eggs awaiting safe and cozy.”

“Did she?”

“When I returned the next morning, the cap, soaked now from the rain, remained undisturbed over the eggs. I was happy to see that the wool had kept the eggs dry and warm through the night.”

“Then what happened?”

“The mother bird never returned. I figured she lost track of her nest because it was hidden by my cap.”

“That is so sad.”

“The story has a happy ending.”

“Then tell me,” I demanded.

“I will, at my own pace. After all, not everything took place at once. There was first one thing, then the other and the other and so forth.”

“What. Happened. Next!”

Pep Saval laughed out loud. “I put my sweater over the eggs to keep them warm. I wanted to be there when the chicks were born.”

“What, for days?” I asked in disbelief.

“For a few hours, as it turned out. Sometime around two in the afternoon, when the heat of the day was crowding in through the still air, I sensed a stirring under the sweater. I lifted up a corner to peek at the eggs. Imagine my surprise when I saw that from one of them, a tiny brown beak was breaking through the shell. Then some chipping started on the other one and finally, by the time the last egg was starting to break, a hole had opened up in the shell of the first one and the head of a wet chick was poking through. It was a scrawny thing that began chirping crazily as soon as it was able to climb out of the egg. A minute later, the bird was joined in the chirping by his two siblings. I can see them still, their eyes closed and filmed over with viscous tears. Their feathers all sticky and matted down. Their beaks opening and closing like tiny pincers as if trying to bite some sustenance out of thin air. Birds are born hungry just like humans. Fortunately I had a jar with a few worms that I’d dug out of the garden that morning.”

“You didn’t say you had worms with you,” I was quick to point out.

“I can’t tell you everything at once,” he argued. “I am telling you now, that when I went up to check on the eggs, I had an inkling that they could be born anytime, and that if their mother was not around to feed them, I would have to provide worms.”

“You are telling me now because you hadn’t thought of it sooner.”

He threw his arms up. “I will not continue the story.”

“Go on, but I won’t believe it.”

“Why would you want hear a story that you don’t believe?”

“Because I want to know how it ends.”

“Come now,” he called up. “It’s getting late.”

“Where are you going?” I asked, suddenly worried I would be left behind.

“I want us to get to Planell before dark.”

“But the story is not over yet.”

“You’ll get the rest of it as we walk.”