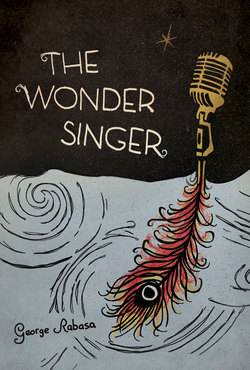

Читать книгу The Wonder Singer - George Rabasa - Страница 21

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFROM THE WONDER SINGER . . .

The Language of Hands

During those first years, I thought of Father every day. I searched for his face in the market crowds and in hostels, listening for his voice amid the lodgers bent over their cards. Along the road, I watched for the distinctive cadence of his walk, the rocking of his body, the puzzled frown of his expression as he ate, unable to enjoy the food until he had discerned its freshness and precise seasoning. I rehearsed what I would say to him: I would pummel his chest and kick his shins and demand to know why he had left me.

“Your father must be dead,” Pep Saval tried to persuade me. “When he stepped out of the inn that day, he left you in my care with every intention to return in the evening after his customer visits.”

“Don’t say that.”

“How else does someone disappear?” he said as if the answer were absurdly self-evident. “Señor Casals loved you and he wanted the best for you. That night, while on his way to see how our first lesson had gone, bandits came upon him on the road and killed him to steal the money he had collected from his sales.”

I stared at him boldly.

“It would do you good to cry for your father,” he said to me.

I remained sullen and dry-eyed, even after he scolded me for having a cold heart. He told me I would never become an artist if I was unable to shed tears.

We had been living in Vals, a town located along the fair circuit where Pep Saval found a ready harvest of easy winnings. We settled into two rooms in a dank, noisy building.

In the larger of the two rooms Pep Saval hung a sheet to divide the main brass bed where he slept from my narrow cot, on which rested a variety of dolls and plush animals. He had bought them for me as we went from town to town whenever I required quick relief from melancholy.

“We will respect each other’s privacy,” he declared. “This curtain is a sacred barrier. May I be damned to hell if I ever violate it.” He crossed himself when he said this, even though I had never known him to acknowledge the existence of God or Joseph, Mary, and Jesus or the Saints. Except for the occasional scatological blasphemy, Em cago en Déu, when things did not go as expected, Pep Saval was happily godless.

The other room contained Pep’s armchair, a table and two stools, a washbasin, a makeshift kitchen organized around a charcoal brazier where a pot of soup continually simmered. The Eternal Soup, Pep called it. I never saw him wash out the pot. When it ran low, he would add water, a couple of carrots, an onion, a potato. There was never meat or chicken in the soup because Pep claimed that animal fats coated the vocal cords and made the voice thick. With the soup there was always pa amb tomàquet made with stale rolls and soft ripe tomatoes.

I shuffled about the rooms in my stocking feet, shoulders slouched, eyes unfocused, red hair stringy and hanging over my face. Every morning while I stood at the small stove heating the milk for morning coffee, Pep Saval greeted me cheerfully: “Bon dia, Senyoreta Mercè.” Then he’d lead me through the basic exercises. I went along grudgingly.

There surely was a hidden reason why this unruly child had landed in his care. Pep’s life had been simple and unencumbered until he’d beaten my father at cards. The result of Father’s bad luck had been Pep’s losing his freedom to enjoy the rewards of a solitary life: to drink and fornicate and curse as exuberantly as only a single man can. I was a curious, skulking waif who had become the censor of his every movement.

Eventually, thoughts of Father receded, and I concentrated on the tasks that Pep Saval set for me. I drilled the pronunciation of German, English, French, and especially Italian by reading libretti. He assigned me deep breathing to increase lung capacity, and posture exercises that he promised would add centimeters to my height just from stretching the spine. “How can you be a queen if you slouch like an urchin?” he would scold.

Because I was still a child, he forbade me to sing to the fullness of my range. Still, if I sang recklessly, he would be caught in the experience when my voice would float on a high C-sharp. He sensed what it was like to be me at that particular moment listening to my own voice pour out as if with a will of its own, and the notes so pure and clear, a warm honey that flooded my mouth with a shocking sweetness.

Meanwhile, Pep Saval’s vague intuition had grown into a conviction that his life would be dedicated to serving my gift. He would teach me, by example, to be a slave to my own talent. But even the most devoted servant needs a regular night out. Pep Saval found a game of set i mig at the nearby Café Jardí where he would earn enough from traveling innocents to pay the rent and keep the soup pot full.

As for me, when Pep Saval left in the evening, I felt as if a weight were lifted. I loved being free of his bullying, his smells of bay rum and cigar smoke, his vigilant gaze. With him away, I was free to brush the tangles out of my hair, comb it back and gather it at the nape with a silver clasp. I would open the score of Bellini’s Norma, at the point where she confronts her lover Pollione and sings, “Trema per te, fellon, pei figli tuoi, trema per me, fellon, ah per me!” (Tremble for yourself, villain, and for your sons, tremble for me, villain, ah, for me!)

I would first declaim the words, standing erect in front of the mirror as befits the posture of the head priestess of the Druids defying the Roman invader and then, following the music, lift my voice into those mysterious forbidden registers. I loved to sing loudly, to open my chest and let my breath push the C out of my throat with so much pain and anger and shock all miraculously compressed into a single note. I was the priestess performing a secret ritual instead of the loneliest girl in the world living in two rooms and not attending school, with not a person in the world to care.

At night I stood in front of the window taking in the cool air, tinged with the smoke of charcoal burners and stoves. Pep Saval would have me shut the window to keep the haze out of my throat. But I was indestructible. I would sing out the window and let the world know who I was.

Vals was not the world. It was a mean little town with unpaved streets that were muddy from spring rains or dusty in the summer or rutted with ice and snow in the winter. The town boasted two spinning and weaving mills and one finishing plant that poured into the river a greenish- brown soup. In summer, families took the train ten kilometers upriver to the town of Oliva, which had no factories except for the press that collected the olives from the surrounding groves for the golden oil that was famous all over Catalonia.

For me, too, a Sunday outing to Oliva was the highlight of the week. On the esplanade outside the church, drummers and pipers would start the impromptu sardanas. Old women and married couples and girls would gather, seemingly out of nowhere, to form the circles. I would find a place in the innermost ring where the expert dancers raised their linked hands and set the count. Pep Saval, an awkward dancer, shuffled along the sidelines.

During the August festival to celebrate the year’s pressing, there was an invasion of jugglers, acrobats, magicians, clowns. Musicians came all the way from Barcelona and Paris. A gypsy encampment settled outside Oliva within a cluster of wagons with flapping canopies and wooden wheels mired in the muddy clearing. Andalusian women with gold bracelets and necklaces jangling with their every move read palms at rough tables covered in threadbare velvet or dirty lace. Pep Saval brushed them away when they tried to sell him charms and amulets. Their hands would be all over him, picking bits of imaginary lint off his coat, smoothing out the wrinkles in his shirt, tugging at his belt, and sneaking into his pockets for loose change. He would triumphantly clutch one by the wrist until she surrendered the stray peseta. He laughed when they stared at his palm, affecting alarm or delight at what it revealed. Whatever he could anticipate happening the day after tomorrow was all the foretelling he needed.

However, the señorita in his charge had a whole life ahead of her, and a hand that had never been read. Here was the real mystery, not the fortunes of a man in the autumn of a battered life, but the fate of a girl with many years to come.

The gypsy held my palm up to her cloudy eyes and began a thin, keening wail. Suddenly she threw off my hand as if it were burning her fingers. I curled it into a fist. After that, there was no getting it to open for a second look. The gypsy’s cries subsided. She shook her head as if she had just gazed into the most dire of fortunes. I curled my hand against the dry, wiry fingers that kept digging under my knuckles trying to pry it open. I kept my hand closed for days.

And for days, I was distracted, lost in an angry turmoil. When my hand did open to grasp something, the palm was red and marked with four deep wedges from my nails. Throughout my life, my marked palms would remind me of the door that had opened a crack and then slammed shut to reveal no more than a sudden glimpse of a black, fat-bellied spider clinging to the inside of my throat. It was all in the open hand, the line of life, the mound of love, the unformed M of death, the crossed paths of lust and loneliness. “Wait,” the gypsy had called after me. “There is more.”

Pep Saval kept trying to set me at ease. The gypsies were meddlesome women who fed off people’s fear and greed and loneliness. “The more you fear your life, the more you will pay for the best possible fortune they can tell. Here are some pesetas. Go back. Tell the old busybody that I insist you be rich and famous and live to a fine old age and die a happy death in the midst of luxury in a foreign land. America will do fine. Ever thought of going to America? That is the place to die. Under big open skies, surrounded by grazing buffalo and the cries of eagles overhead. Don’t die in Spain, all shriveled up on a wooden table surrounded by wailing old women, hovering about like crows, scheming to plunder whatever you’ll leave behind. Believe me, you will be different. The rest of us, your father, the man you will marry, your friends and teachers and colleagues, will all die like lost dogs on strange roads. You, however, will die a queen. Go to the fortune-teller again. Show her your hand. That’s what she will tell you.”