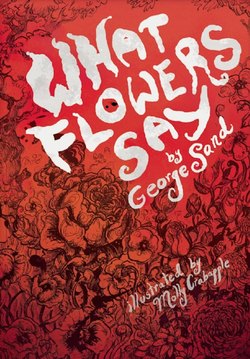

Читать книгу What Flowers Say - George Sand - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Talking Oak

Once upon a time in the forest of Cernas, in central France, there was a big, old oak tree, which could very well have been five hundred years old. Lightning had struck it several times, and it had had to grow a new crown, a little flattened, but thick and green.

This oak tree had had a bad reputation for a long time. The oldest people in the neighboring village were still saying that in their youth this oak would talk—and would threaten those who wanted to rest in its shade. They told the story of two travelers who had been struck by lightning when they were looking for shelter. One of them had died immediately; the other had escaped in time and was only stunned because he had been warned by a voice that had cried out to him, “Get away, quickly!”

The story was so old that people hardly believed it anymore, and even though the tree still bore the name “Talking Oak,” young shepherds would come near it quite fearlessly. After Emmi’s adventure, however, it developed a reputation of being bewitched more than ever.

Emmi was a poor little swineherd, orphaned and very unhappy, partly because he was poorly housed, poorly fed, and poorly dressed, but even more because he hated the pigs that poverty forced him to care for. He was afraid of them, and the pigs, who are more shrewd than they seem, could sense that he wasn’t in control. He went out in the morning, leading them in search of acorns in the forest. In the evening he would bring them back to the farm. How pitiful it was to see him, covered in dirty rags, his head bare, his hair standing on end from the wind, his poor little face pale, thin, dirty, sad, afraid, and suffering, chasing his herd of squealing beasts, who looked at him with sidelong glances, heads lowered and always threatening. To see him run after them on the dark moors, in the red mist of early dusk, you would have thought of a marsh fire chased by a gust of wind.

This poor little swineherd could have been lovable and good-looking, however, if he had been cared for, clean, and happy like you, my dear children, who are reading my story. But he didn’t even know how to read; he knew nothing, and he could barely speak to ask for what he needed. Since he was timid, he didn’t always do that. Whose fault was it if everyone forgot him?

One evening the pigs returned to the barn by themselves, and the swineherd did not appear at suppertime. His absence was noticed only after the turnip soup had been eaten, and the farmer’s wife sent one of the boys to call him. The boy came back to say that Emmi was neither in the barn nor in the loft, where he slept in the hay. They thought he had gone to see his aunt, who lived nearby, and they went to bed without giving him another thought.

The next morning, they went to his aunt’s house, and were surprised to learn Emmi had not spent the night with her. He hadn’t appeared in the village since the night before. They inquired about him in the neighborhood; no one had seen him. They looked in vain in the forest. They thought the wild boars and the wolves had eaten him. However, they found neither his weeding hoe—a kind of forked prod with a short handle that swineherds use—nor a single rag of his poor clothes; they decided he had left the neighborhood to live the life of a wanderer. The farmer said it was no great loss; the child was good for nothing, didn’t like his pigs, and didn’t know how to make them like him.

A new swineherd was hired for the rest of the year, but Emmi’s disappearance frightened all the boys in the neighborhood. The last time Emmi had been seen, he had been near the Talking Oak, and that was probably where something bad had happened to him. The new swineherd took care never to lead his herd over there, and the other children were wary of playing near it.

You ask me what became of Emmi? Patience, I am going to tell you.

The last time he had gone into the forest with his animals, he had noticed a clump of wild sweet peas in bloom a short distance from the big oak tree. The wild sweet pea, or tuberous groundnut, is that pretty papilionaceous plant you have seen that has butterfly-shaped flowers in pink clusters. The tubers are as big as hazelnuts, a little bitter even though they are sweet. Poor children are fond of them; it is a food that costs nothing. But only pigs, who like them too, think of fighting for them. When people talk about the ancient hermits living on roots, you can be sure that the most sought-after food in their austere diet, here in central France, was the tuber of this pea vine.

Emmi knew very well that the groundnuts could not yet be good to eat, because it was only the beginning of autumn, but he wanted to mark the spot so he could come and dig in the dirt when the stalks and the flowers were dry. He was followed by a young pig who began to dig; he was threatening to uproot everything, when Emmi, annoyed to see the wanton destruction of the gluttonous beast, smacked him a good one on the snout with his hoe. The iron on the hoe was newly sharpened and cut the pig’s nose slightly, and the pig let out a cry of alarm. You know how animals stand by each other, and how certain distress calls put them all in a rage against a common enemy. Besides, the pigs had had a grudge against Emmi for a long time because he never lavished flattery or compliments on them. They got together, each trying to squeal louder than the other, and surrounded him, trying to eat him. The poor child ran for his life, but they followed him. These beasts, you know, can run frightfully fast; he barely had time to reach the big oak tree, scramble up its gnarled trunk, and hide in its branches. The savage herd stayed at the foot of the tree, squealing, threatening, trying to uproot it. But the Talking Oak had tremendous roots that could hardly take a herd of pigs seriously. The attackers, however, didn’t give up trying until after the sun set. Then they decided to go back to the farm, and little Emmi, certain they would eat him if he went with them, decided never to return.

He was well aware that the oak was considered a bewitched tree, but he had been the victim of real, living people too often to be very much afraid of spirits. All his life he had known only poverty and beatings. His aunt was very hard on him: she forced him to guard the farmer’s pigs, though he had always been afraid of them. When he went to see her, begging her to take him back, she greeted him, as they say, with a good beating. So, he was really afraid of her, and his only desire was to become a shepherd on another farm where the people might be less stingy and not so mean to him.