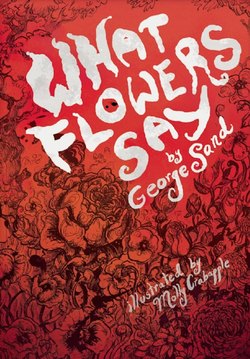

Читать книгу What Flowers Say - George Sand - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWhat Flowers Say

When I was a child, my dear Aurore, I was tormented by the fact that I wasn’t able to hear what flowers said when they talked to each other. My botany professor assured me they said nothing. Whether he was deaf or he didn’t want to tell me the truth, he swore they said nothing at all.

I knew he was wrong. I would hear them chattering, especially in the evening when the dew began to form; but they spoke too low for me to make out their words. Furthermore, they were distrustful, and when I would walk by the flower beds or along the path in the meadow, they would warn each other with a sort of “shhh,” which they passed from one to the other. It was as if they said from start to finish, “Watch out, be quiet! Here comes that curious little girl who listens to us.”

But I persisted. I practiced walking very quietly without disturbing the smallest blade of grass, so they wouldn’t hear me and so I could get very, very close. Then, by bending way down under the shade of the trees so they couldn’t see my shadow, I finally heard some words clearly.

I had to pay close attention. The little voices were so soft and low that the least little breeze would carry them away, and the humming of sphinx moths and other night moths would cover their voices completely.

I don’t know what language they were speaking. It wasn’t my native French or the Latin I was studying at that time. But it so happened that I was able to understand it very well. It even seemed to me I could understand this language better than any I had heard before.

One evening, I managed to lie down on the sand in a sheltered corner of the border and hear everything that was said near me. Everyone was talking throughout the garden, but I knew I couldn’t catch more than one secret at a time. I stayed in the corner very quietly and here is what I heard from the poppies: “Ladies and gentlemen, it is time to be done with these trite remarks. All plants are equally noble; our family bows to no one and anyone who wants to can accept the royalty of the rose. But I proclaim that I’ve had enough of this and I give no person the right to say he or she is better born or more titled than I.”

To this the chrysanthemums answered in unison that the poppy speaker was right. One of them, who was larger and more beautiful than the others, asked to speak and said: “I have never understood the airs the rose family puts on. How, I ask you, is a rose better made or prettier than I am? Nature and art got together to increase the number of our petals and the brilliance of our colors. We are even more opulent in shape, because the most beautiful rose has hardly more than two hundred petals and we have almost five hundred. As far as colors are concerned, we have purple and almost a true blue, something the rose will never have.”

“As for me,” said a large perennial larkspur, “I am the Prince Delphinium. I have the azure blue of the skies in my corolla and my many relatives have all the shades of pink. So the so-called queen of the flowers has a lot to be envious about and as for her highly praised fragrance . . .”

“Don’t get into that!” blustered the poppy. “All that bragging about fragrance gets on my nerves. What, I ask you, is fragrance? A tradition established by gardeners and butterflies. Frankly, I think the rose smells terrible and I’m the one who is fragrant.”

“We don’t smell at all,” said the chrysanthemum, “and that way we show good manners and good taste. Odors are indiscreet and boastful. Any plant who respects herself doesn’t announce her arrival with a scent. Her beauty should suffice.”

“I don’t agree,” cried a large, white poppy who gave out a strong smell. “Odors indicate wit and good health.”

Laughter drowned out the voice of the big poppy. The carnations held their sides and the mignonettes were convulsed with laughter. But instead of getting angry he started again to criticize the shape and the color of the rose, who couldn’t answer. All the rosebushes had just been pruned and the growing sprouts still had only small buds, tightly wrapped in their little, green blankets. A very richly dressed pansy bitterly criticized the many-petaled flowers, and, since the latter were a majority in the flower bed, they all began to get angry. But there was so much jealousy toward roses that they made peace with one another in order to scoff and jeer at them again. The pansy was even applauded when she compared a rose to a large, firm, round cabbage, preferring the cabbage because of her size and usefulness. All this foolishness that I was hearing exasperated me and suddenly, speaking their language and kicking those silly flowers, I screamed: “Be quiet! You’re all talking nonsense. I expected to hear the wonders of poetry here. What a disappointment for me to hear about your rivalries, your boasting, and your petty jealousy!”

There was a prolonged silence and I left the flower bed.

I’ll just go see, I said to myself, if wild flowers have more common sense than those cultivated ninnies, who, receiving their borrowed beauty from us, seem to have also taken on our prejudices and our shortcomings.

I crept along in the shadow of the bushy hedge, heading toward the meadow. I wanted to know if the spirea, who are called queens of the meadow, were also proud and jealous. But I stopped next to a tall wild rosebush, where the flowers were all talking to one another.

“Let’s try to find out,” I was thinking, “if the wild rose makes fun of the cabbage rose with a hundred petals and scorns the button rose.”

I must tell you that, in my day, they hadn’t created all the varieties of roses that learned gardeners have since produced by grafting and by developing new seeds. Nature wasn’t poorer because of it. Our bushes were filled with numerous varieties of roses that were very hardy: the canina, so named because people thought it was a remedy for mad dog bites; the cinnamon rose; the musk rose; the rubiginosa, or the rusty rose, which is one of the prettiest; the Scotch rose; the tomentosa, or the cottony rose; the alpine rose, and so on. Back then, in our gardens, we had charming species that are almost lost today. There was a red-and-white variegated rose that didn’t have many petals but displayed her crown of stamens in a beautiful bright yellow and smelled like orange blossoms. It was as hardy as could be, fearing neither dry summers nor hard winters. There were also button roses, small and large varieties, which have become especially rare, and the little May rose, the most precocious and perhaps the most fragrant of all, which you cannot find today in the shops. We also had the damask, or French, rose, which we knew how to use and you can only get now in the south of France, and finally the hundred-petal rose, or rather, the cabbage rose. No one knows what country it comes from and people usually attribute its development to cultivation.

The cabbage rose—centifolia—was then, for me as well as for everyone, the ideal rose, and I wasn’t convinced, as was my tutor, that it was a monster created by horticulturists. I read in my poetry books that the rose was, from the beginning of time, the ideal of beauty and fragrance. Today’s tea roses, which don’t even smell like roses, were unknown, as were all these charming varieties that change endlessly, and have fundamentally altered the standard of what a true rose should be.

I was studying botany at the time. I studied it in my own way. I had a very acute sense of smell and I expected the fragrance to be one of the essential qualities of the plant. My teacher, who took snuff, would not agree to this criterion of classification. He could no longer smell anything but tobacco, and when he sniffed another plant, it would make him sneeze shamefully. So I listened carefully to what the wild roses were saying over my head, because, from the very first, I could tell they were talking about the origins of the rose.

“Stay here, sweet West Wind,” the wild roses were saying. “We have blossomed. The beautiful roses of the flower beds are still sleeping in their green buds. See, we are fresh and cheerful, and if you rock us a little, we will scatter our fragrance, which is as sweet as the fragrance of our famous queen.”

Then I heard the West Wind say, “Be quiet, you are only children from the North. I’ll stay and chat with you, but don’t dare to compare yourselves to the queen of flowers.”

“Dear West Wind, we respect and worship her,” answered the flowers of the rosebush. “We know how jealous the other garden flowers are of her. They claim she is no better than we are, that she is our daughter and owes her beauty merely to grafting and cultivation. We’re not very smart and we don’t know how to answer them. Tell us, because you’ve been around longer than we have on this earth, tell us the true origin of the rose.”

“I’ll tell you, because it is my story, too. Listen and don’t ever forget it.”

And the West Wind began his story:

“Back in the times when beings and things of the universe still spoke the language of the gods, I was the eldest son of the King of Storms. My black wings touched the two extremities of the wide horizons. My immense head of hair was tangled in the clouds. My appearance was terrifying and dazzling. I had the power to gather the thick clouds of the setting sun and spread them like an impenetrable veil between the earth and the sun.

“For a long time I reigned with my father and brothers over the barren earth. Our mission was to destroy and disrupt. My brothers and I, unleashed to all four corners of this wretched little world, looked as if we would never allow life to appear on this misshapen cinder that today we call the land of the living. I was the strongest and the most violent of all. When my father, the king, was tired, he would spread above the clouds and give me the job of continuing the relentless destruction. But in the heart of this still, lifeless earth, a spirit was moving, a powerful goddess, the Spirit of Life, who wanted to be born. By crumbling mountains, filling up oceans, and piling up dust, suddenly one day she began to spring up everywhere. We increased our efforts but only managed to hasten the birth of a multitude of beings, who escaped us, either because they were so small or because they were so weak. Lowly little flexible plants, tiny floating shellfish, would find places for themselves in the still, warm surface of the earth’s crust, in the silt, in the waters, in all kinds of debris. In vain, we would madly flood these upstart creations. Life constantly came into being and appeared in new forms, as if a patient and inventive genie of creation had decided to adapt the organs and the needs of all of these beings to the tormented environment we made for them.

“We began to tire of their resistance, which appeared to be passive but in reality was invincible. We destroyed entire races of living beings—others would appear, organized to withstand us without being killed. We were exhausted with rage. We retreated above the cloud cover to deliberate and ask our father for new strength.

“While he was giving us instructions, the earth, delivered for an instant from our fury, became covered with innumerable plants where myriads of animals, cleverly adapted within our different species, found shelter and food in huge forests or on the sides of mighty mountains, as well as in the purified waters of immense lakes.

“‘Go,’ said my father, the King of Storms, ‘Here is the earth who has adorned herself like a bride to marry the sun. Put yourselves between them. Pile up enormous thunderheads, roar, and may your breath flatten the forests, level the mountains, and unleash the seas. Go and don’t come back as long as there is a living being or a plant standing on this cursed arena where life wants to establish itself in spite of us.’

“We scattered like seeds of death over the two hemispheres. Like an eagle, I tore through the curtain of clouds and swept down on the ancient countries of the Far East. There deep valleys slope toward the ocean from the high Asiatic plateaus under a fiery sky and, bathed in a swamp of humidity, give birth to gigantic plants and fearsome animals. I had rested from my earlier tiredness, I felt endowed with an incomparable strength, and I was proud to bring disorder and death to all these weaklings trying to defy me. With one flap of a wing, I flattened an entire country; with one puff, I knocked down a whole forest, and I felt within me a blind, drunken joy, the joy of being stronger than all the forces of nature.

“Suddenly a perfume entered me as if I had inhaled something foreign into my body, and surprised by this new experience, I stopped to gather my senses. Then, for the first time, I saw a being who had appeared on the earth while I was gone, a new, delicate, almost imperceptible being—the rose!

“I swooped down to crush her. She bent over, lay down on the grass and said, ‘Have pity on me! I am so beautiful and sweet! Sniff me and you will spare me.’

“I sniffed her and a sudden exhilaration overcame my fury. I lay down on the grass and fell asleep beside her.

“When I woke up, the rose had stood up again and was swaying softly, rocked by my now calmed breath.

“‘Be my friend,’ she said. ‘Don’t leave me again. When your terrible wings are folded, I love you, and I think you are beautiful. No doubt you are the King of the Forest. Your softened breath is a delicious song. Stay with me and take me with you, so I can go see the sun and the clouds close up.’

“I took the rose to my breast and flew away with her. But soon it seemed to me she was wilting. Listless, she could no longer talk to me; her fragrance, however, continued to enchant me. Afraid that I would destroy her, I flew quite slowly. I gently brushed the treetops, avoiding the least little bump. I climbed cautiously to the palace of dark clouds where my father was waiting for me.

“‘What are you doing?’ he said. ‘And why is that forest I see on the shores of India still standing? Return immediately and wipe it out.’

“‘Yes,’ I answered, showing him the rose, ‘but let me entrust to you this treasure I want to save.’

“‘Save!’ he cried, roaring in anger. ‘You want to save something?’

“And with one breath, he tore the rose from my hand and she disappeared into space, scattering her wilted petals.

“I lunged to try to capture at least a remnant; but the king, irritated and implacable, seized me in turn, turned me over his lap and violently tore off my wings. My feathers went flying into space to join the scattered petals of the rose.

“‘You wretched child,’ he told me, ‘you felt pity! You are no longer my son. Go back to earth and join up with that disastrous Spirit of Life that defies me. We’ll see if she can make anything of you, because now, thanks to me, you are nothing.’

“And throwing me into the pit of emptiness he forgot me forever.

“I tumbled as far as a clearing and lay exhausted beside the rose, who was happier and more fragrant than ever.

“What is this miracle? I thought you were dead and I cried for you. Do you have the gift of life after death?

“‘Yes,’ she answered, ‘like all creatures whom the Spirit of Life enriches. Look at these buds that surround me. This evening I will have lost my brilliance and I will work to renew myself, while my sisters charm you with their beauty and pour their perfumes over you in their day of celebration. Stay with us. Aren’t you our companion and our friend?’

“I was so humiliated by my dethronement, that with my tears I watered the earth, to which I felt bound forever. The Spirit of Life felt my tears and was moved by them. She appeared to me in the form of a radiant angel and said, ‘You felt pity, you pitied the rose. I want to have pity on you. Your father is powerful, but I am more powerful than he is. He can destroy, but it is I who create.’

“While she was saying this, the shining being touched me, and my body became like that of a beautiful child with a face the color of a rose. Butterfly wings sprouted from my shoulders and I started to flutter about with sheer delight.

“‘Stay with the flowers, in the cool shelter of the forests,’ said the goddess. ‘For now, these canopies of greenery will hide and protect you. Later, when I have conquered the rage of the elements, you will be able to travel the earth, where you will be blessed by the people and celebrated by poets.’

“‘As for you, charming rose, the first to be able to disarm anger with beauty, you are to be the symbol of the future reconciliation of forces that are enemies of nature. You will also be the educator of future races, because those civilized races will want to make everything serve their own needs. My most precious gifts—grace, gentleness, and beauty—will be in danger of seeming to have less value than money and power. Teach them, kind rose, that the greatest and most legitimate power is that which charms and reconciles. Now I give you the title that future generations will not dare take away from you. I proclaim you Queen of the Flowers. The ranks that I establish are divine and have only one means of expression—charm.’

“Since that day, I have lived in peace with the heavens, loved by people, animals, and plants. My free and divine beginnings allow me the choice of living where I please, but I am too much a friend of the earth and servant of the life that my beneficial breezes sustain, to leave this dear earth where my first and eternal love keeps me. Yes, my dear little ones, I am the rose’s faithful lover and consequently your brother and your friend.”

“In that case,” cried all the little roses on the wild rosebush, “take us dancing and celebrate with us, singing praises to the queen, the hundred-petaled rose of the East.”

The West Wind fluttered his pretty wings, and over my head there was a joyful dance, accompanied by the beating branches and clicking leaves acting as kettle drums and castanets. A few of the happy little ones tore their ball gowns and strewed their petals in my hair, but they didn’t notice. They danced very beautifully and as they sang, “Long live the beautiful rose whose sweetness conquered the son of thunderstorms! Long live the good West Wind who remained a friend to the flowers!”

When I told my tutor what I had heard, he announced that I was sick and should be given medication. But my grandmother saved me from that by telling him, “I feel sorry for you if you have never heard what roses say. As for me, I miss the days when I was able to hear them. It’s a talent that children have. Be careful not to confuse talent with illness.”