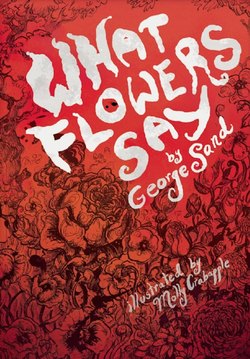

Читать книгу What Flowers Say - George Sand - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Bug-Eyed Fairy

Elsie had a very peculiar Irish governess. She was the nicest person in the world, but there were certain animals she found so unpleasant that she would fly into veritable fits of rage against them. If a bat entered her quarters in the evening, she would scream without apparent reason and become indignant toward anyone who would not chase after the poor creature. Since a lot of people are repulsed by bats, no one would have noticed her hostility toward them, except that she felt the same way about lovely birds: warblers, robins, swallows, and other insectivores, not to mention nightingales, which she called cruel beasts. Her name was Miss Barbara—but they called her “Bug-Eyed Fairy”—“Fairy” because she was very learned and very mysterious, and “Bug-Eyed” because she had huge, clear, bulging round eyes, which mischievous Elise compared to glass bottle stoppers.

However, Elsie didn’t hate her governess, who was the epitome of indulgence and patience with Elsie. She just liked to make fun of Miss Barbara’s peculiarities and especially her pretense of seeing better than everyone else, even though she could have won first prize for nearsightedness in a military medical contest. She didn’t even know she was near an object unless she touched it with her nose, which, unfortunately, was extremely short.

One day when Miss Barbara had bumped her head on a half-opened door, Elsie’s mother said, “Really, one of these days you’re going to hurt yourself badly! I’m telling you, my dear Barbara, you should wear glasses.”

Miss Barbara answered sharply, “Me? Glasses? Never! I’m afraid they’d spoil my vision!”

When they tried to make her understand that her vision couldn’t get any worse, she protested, with an air of triumphant conviction, that she wouldn’t trade “the treasures of her vision” with anybody. She saw the tiniest little objects the way others saw them through the strongest magnifying glasses; her eyes were two microscope lenses continually revealing marvels that no one else could see. The fact is, she could count the threads of the finest cloth and the stitches of the most delicate fabrics, while Elsie, who had so-called good eyes, saw absolutely nothing.

For a long time, they called her Mademoiselle Grenouille (Miss Frog), and then they called her Mademoiselle Hanneton (Miss Maybug), because she banged into things everywhere. Finally, the name Bug-Eyed Fairy prevailed because she was too well educated and too intelligent to be compared to an animal, and also because everyone, seeing the eyelet and the other marvelous embroidery that she knew how to do, would say, “She’s a true fairy!”

Miss Barbara wasn’t indifferent to this compliment, and she usually would reply, “Who knows? Maybe! Maybe!”

One day, Elsie asked her if she was serious when she said that, and Miss Barbara cleverly repeated, “Maybe, my dear child, maybe!”

That was all that was needed to arouse Elsie’s curiosity. She no longer believed in fairies, for she was twelve years old. But she regretted not believing anymore, and you wouldn’t have had to ask her twice for her to believe again.

The fact is, Miss Barbara had some strange habits. She hardly ate anything and hardly ever slept. They weren’t even sure that she did sleep, because no one had ever seen her bed unmade. She said that she remade it herself each day, early in the morning when she woke up, because she could only sleep in a bed that was made to her liking. In the evening, as soon as Elsie left the parlor with her maid, who slept next to her, Miss Barbara would eagerly retire to the summerhouse that she had requested for her living quarters, and it was said you could see a light burning there until daybreak. It was even claimed that, at night, she would walk with a little lantern, talking out loud to invisible beings.

Elsie’s maid talked about Miss Barbara’s activities so much that, one fine evening, Elsie felt an irresistible desire to see them for herself, to discover the mysteries of the cottage. But how would she dare go to such a place at night? She would have to walk at least two hundred feet through a clump of lilacs over which a large cedar grew, and under this dual shadow, follow a narrow, winding path that was dark, dark, dark!

“Never,” thought Elsie. “I’ll never have the courage to do it.”

The servants’ silly gossip had frightened her, and she didn’t chance it. But the next day she did risk asking Miss Barbara about what she did during her long evenings.

“I stay busy,” the Bug-Eyed Fairy answered gently. “My whole day is dedicated to you; the evening belongs to me. I use it to work for my own betterment.”

“So, you don’t know everything, since you still study?”

“The more you study, the better you can see that you still know nothing.”

“But what do you study so much? Latin? Greek?”

“I know Latin and Greek. I’m busy with other things.”

“What? Don’t you want to tell?”

“I look at things that only I can see.”

“What do you see?”

“Please don’t ask me to tell you; you’d want to see it too, and you wouldn’t be able to or you’d see it poorly, which would be a disappointment to you.”

“Is what you see very beautiful?”

“More beautiful than everything you have seen or will ever see in your dreams.”

“Dear Miss Barbara, show it to me, I beg you!”

“No, my child, never! It’s not up to me.”

“Well, I will too see it!” shouted Elsie, becoming quite distraught. “I’ll come to your house at night and you won’t turn me out.”

“I don’t think you’re likely to come. You would never dare come!”

“You mean I’ll need courage to come to your nighttime ceremonies?”

“You’ll need patience, and you have absolutely none.”

This angered Elsie and she changed the subject. Later she returned to her argument and pestered the governess so much that Miss Barbara promised to take her to her summerhouse that evening, but she warned Elsie she would see nothing or would understand nothing that she might see. See! See something new, unknown! What curiosity, what excitement for an inquisitive little girl! Elsie didn’t feel like eating her dinner. She bounced around on her chair uncontrollably, she counted the hours, the minutes. Finally, after the evening’s occupations, she got permission from her mother to go to the summerhouse with her governess.

They were barely into the garden when they met someone who appeared to make Miss Barbara very nervous. It was only Mr. Bat, Elsie’s brothers’ tutor, a very inoffensive-looking man. He wasn’t handsome: he was thin, with a pointy nose and ears, and always dressed from head to toe in black. He wore coats with tails, very pointy also. He was shy, even timid; after lessons, he would disappear as if he needed to hide. He never spoke at the table, and in the evening, while waiting to supervise the children’s bedtime, he would walk in circles around the terrace in the garden, which was harmless but appeared to be an indication of a shallow mentality, given to foolish idleness. Miss Barbara didn’t think of him that way. She was terrified of Mr. Bat, first of all because of his name. She claimed that when a person had the misfortune to have such a name, he should leave the country and take another name. She had all sorts of prejudices against him. She held it against him that he had a good appetite, and she thought he was gluttonous and cruel. She contended that his strange circular walks were an indication of the most harmful inclinations and concealed the most sinister intentions.

Therefore, when she saw him on the terrace, she shuddered. Elsie, who was clinging to Miss Barbara’s arm, felt it tremble. What was so astonishing about the fact that Mr. Bat, who loved the fresh air, was outside until his pupils’ bedtime? They went to bed later than Elsie, the youngest of the three. Miss Barbara was nonetheless shocked by this behavior, and walking past him, she couldn’t keep from saying dryly, “Do you plan to stay out here all night?”

Mr. Bat started to run away, but, afraid of being impolite, he tried to answer with a question.

“Does my presence bother anyone, and do they want me to go back in?”

“I have no orders to give you,” continued Miss Barbara sharply, “but I’m inclined to believe you’d be better off in the parlor with the family.”

“I’m uncomfortable in the parlor,” the tutor answered modestly. “My poor eyes suffer terribly from the heat and the bright light of the lamps.”

“Oh! Your eyes can’t stand the light? I knew it! Twilight is the most light your eyes need? Would you like to be able to fly in circles all night long?”

“Of course!” answered the tutor, trying to laugh and be pleasant. “I’m ‘batty,’ aren’t I?”

“It’s nothing to brag about!” cried Miss Barbara, trembling with anger.

And she dragged Elsie, dumbfounded, into the dark shadows of the little pathway.

“His eyes, his poor eyes!” repeated Miss Barbara, with a convulsive shrug of her shoulders. “I can’t feel sorry for you, you savage beast!”

“You’re very hard on that poor man,” said Elsie. “His eyes really are so sensitive that he can no longer see in the light.”

“No doubt, no doubt! But how he makes up for it in the darkness! He’s hemeralopic, and what’s more, he’s presbyopic.”

Elsie didn’t understand these epithets, which she supposed were degrading, and didn’t dare ask for an explanation. She was still in the shadowy pathway, which she didn’t like one bit, but she finally saw the tree-covered walk open in front of her. The summerhouse was appearing beyond it, whitened by the light of the rising moon, when suddenly she drew back, forcing Miss Barbara to draw back too.

“What is it?” asked the lady with the big eyes, who saw nothing at all.

“It’s . . . it’s nothing,” answered Elsie, embarrassed. “I saw the dark form of a man in front of us, and now I can make out Mr. Bat crossing by the door to your summerhouse. He’s walking in your flower border.”

“Ah!” cried Miss Barbara indignantly. “I should have expected it. He follows me, he spies on me, he’s trying to ruin my life. But don’t be afraid, dear Elsie, I’ll give him what he deserves.”

Miss Barbara rushed forward.

“Aha! Sir,” she said, talking to a large tree against which the moon cast strange shadows. “When will you stop pestering me with your harassments?”

She was going to scold him properly, when Elsie interrupted her and led her toward the door to the summerhouse, saying, “Dear Miss Barbara, you’re mistaken. You think you’re talking to Mr. Bat but you’re talking to your shadow. Mr. Bat is already gone. I don’t see him anymore and I don’t think he was trying to follow us.”

“Frankly, I don’t agree with you,” answered the governess. “How can you explain the fact that he arrived ahead of us, since we left him behind, and we neither saw nor heard him pass by us?”

“He could have walked through the flower beds,” answered Elsie. “It’s the shortest way and it’s the way I often go when the gardener isn’t looking.”

“No, no!” said Miss Barbara distressfully, “he went over the trees. Look, you can see far, look over your head! I bet he’s lurking in front of my windows!”

Elsie looked and saw only the sky, but, after a minute, she saw the moving shadow of a huge bat pass back and forth on the cottage walls. She didn’t want to say anything to Miss Barbara, whose obsessions were making Elsie impatient because they were keeping her from satisfying her curiosity. Elsie urged her to go into the summerhouse, saying that there were neither bats nor tutors spying on them.

“Besides,” she added, entering the little parlor on the first floor, “if you’re worried, we could close the windows and curtains very tightly.”

“Now that is impossible!” answered Miss Barbara. “I’m giving a ball and my guests must come through the window.”

“A ball!” cried Elsie, dumbfounded. “A ball in this little cottage? Guests who enter through the window? You’re making fun of me, Miss Barbara.”

“It’s a ball, I say. A grand ball,” answered Miss Barbara, lighting a lamp, which she placed on the windowsill. “Magnificent costumes, unbelievable luxury!”

“If that’s true,” said Elsie, shaken by her governess’s confidence, “I can’t stay here in this old dress I have on. You should have warned me. I would have put on my pink dress and my pearl necklace.”

“Oh! My dear girl,” answered Miss Barbara, placing a basket of flowers next to the lamp. “It would do you no good to cover yourself in gold and jewels—you could never compare with my guests.”

Elsie, a little mortified, said nothing. Miss Barbara put some water and honey in a saucer and said, “I’m preparing the refreshments.”

Then, suddenly, she cried out, “Here’s one now! It’s the princess moth, the Nepticula marinicollella, in her black velvet tunic crossed with a large band of gold. Her dress is of black lace with a long fringe. Let’s present her with an elm leaf; it’s the palace of her ancestors where she was born. Wait! Give me that leaf from the apple tree for her first cousin, the beautiful Malella, whose black dress has silver stripes and a skirt fringed in pearly white. Give me some flowering broom, to brighten the eyes of my dear Cemiostoma spartifoliella, who is approaching in her white gown with black and gold accents. Here are some roses for you, Marquise Nepticula centifoliella. Just look, dear Elsie! Look at this dark red tunic, trimmed in silver. And these two illustrious blue moth Lavernides: lineela, who is wearing an orange scarf embroidered in gold over her dress, while schranckella has an orange scarf striped with silver. What taste, what harmony in these gaudy colors, softened by the velvety fabrics, the transparency of the silky fringes, and the delightful patterns! The Adelida panzerella is wrapped in gold, embroidered with black; her skirt is in lilac with gold fringe. Finally, here’s the pyralid moth rosella, one of the most simply dressed, who has an overdress of bright pink tinted with white on the borders. What a pleasant effect the underdress of light brown has! She has only one fault, which is that she’s a little too tall. But here’s a group of really exquisite little creatures. These are the Tineidae, or clothes moths, some dressed in brown and studded with diamonds, others in white with pearls on gauze. Dispunctella has ten drops of gold on her silver dress. Here are some important people of rather imposing size—the Adelidae family with their antennae twenty times longer than their bodies. Their clothes are green-gold with red or violet highlights, which remind you of the necklaces of the most beautiful hummingbirds.

“And now, look! Look at the crowd pushing to get in! There are more and still more coming! Elsie, you won’t know which one of these queens of the evening to admire the most for the splendor and the exquisite taste of her attire. The tiniest details of the bodice, the antennae, and feet are unbelievably delicate, and I don’t think you have ever seen such perfect creatures anywhere. Now, notice the grace of the movements, the crazy and charming haste in flight, the flexibility of their antennae, with which they talk to each other, the gentleness of their bearing. Elsie, isn’t it an incredible celebration, and aren’t all other creatures ugly, freakish, and sorry-looking in comparison?”

“I’ll say anything to make you happy,” answered a disappointed Elsie, “but to tell the truth, I see nothing, or practically nothing of what you’re describing so enthusiastically. I can see little microscopic butterflies flying around those flowers and the lamp, but I can hardly make out bright specks and dark specks, and I’m afraid you’re drawing on your imagination for the brilliance you like to dress them in.”

“She doesn’t see! She can’t make them out!” the Bug-Eyed Fairy cried unhappily. “Poor little thing! I knew it! I warned you that your disability would keep you from seeing the joys I relish. Fortunately, I know how to compensate for your weak vision. Here is an instrument that I, myself, never use, which I borrowed from your parents for you. Take it and look.”

She gave Elsie a very strong magnifying glass, which caused Elsie some difficulty, since she had never used one. Finally, after a few tries, she succeeded in making out the real and surprising beauty of one of the little creatures. She focused on another and saw that Miss Barbara has not misled her: gold, purple, amethyst, garnet, orange, pearl, and pink combined to form symmetrical adornments on the coats and dresses of these almost imperceptible dignitaries. She innocently asked why so much richness and beauty were lavished on creatures who lived only a few days at the most and who flew at night, barely visible to humans.

“There it is!” answered the Bug-Eyed Fairy, laughing. “Always the same question! My dear Elsie, grown-ups ask the same question, which means they don’t have any better idea of the laws of the universe than children. They believe everything was created for them and what they don’t see or don’t understand shouldn’t exist. But I, the Bug-Eyed Fairy, as they call me, know that what is simply beautiful is as important as what is useful to people, and I rejoice when I contemplate marvelous things or creatures that no one dreams of making use of. There are thousands and thousands of millions of my dear little moths spread over the earth. They live modestly with their families on little leaves, and no one has yet thought of harassing them.”

“That’s true,” said Elsie. “But birds, warblers, and nightingales eat them, not to mention bats!”

“Bats! Oh! You just reminded me! The light that attracts my poor little friends and allows me to study them also attracts bats—horrible beasts who prowl around all night long, mouths open, swallowing everything they run into. Come, the ball is over, let’s put out the lamp. I’ll light my lantern, since the moon has set, and I’ll take you back to the house.”

As they walked down the front steps of the summerhouse, Miss Barbara added, “I warned you, Elsie. You have been disappointed in your expectations, you only imperfectly saw my little night fairies and their fantastic dance around my flowers. With a magnifying glass you can only see one object at a time, and when the object is alive, you only see it at rest. But I see my whole, dear little world at once; none of its elegance and extravagance escapes me. I showed you very little of it today. It was too cool this evening and the wind wasn’t coming from the right direction. On stormy nights, I see thousands of millions take refuge in my home, or I pay them a surprise visit in their shelters of foliage or flowers. I have told you the names of a few of them, but there are vast numbers of others, which, depending on the season, are born to a short existence of ecstasy, finery, and celebration. We don’t know all of them, even though some very patient and knowledgeable people study them carefully and have published huge volumes where they are wonderfully portrayed—and enlarged for people with weak eyes. But these books are incomplete, and every gifted and well-intentioned person can add to the scientific catalog through new discoveries and observations. As for me, I’ve found a large number that have not yet had their names or their pictures published, and I’m trying hard to make up for the ingratitude and disdain that science has shown them. It is true they are so very, very small, that few people bother to look at them.”

“Are there any smaller than the ones you have shown me?” asked Elsie, who, seeing that Miss Barbara had stopped on the steps, leaned on the handrail.

Even though Elsie had stayed up later than usual, she hadn’t had quite the surprise and good time that she had expected, and she had begun to feel sleepy.

“There are infinitely small beings, which should not be treated disrespectfully,” replied Miss Barbara, who didn’t notice her pupil’s sleepiness. “There are some that can’t be seen by humans even when they are enlarged as much as possible by instruments. At least that is what I presume and believe, and I see more than most people can see. Who can say at what size, visible to us, the life of the universe stops? Who can prove that fleas don’t have fleas, which in turn nurture fleas which nurture others, and so on into infinity? As far as moths are concerned, since the smallest we can perceive are unquestionably more beautiful than the large ones, there is no reason a throng of others doesn’t exist, still more beautiful and smaller, which scientists would never suspect.”

Miss Barbara got this far in her argument without realizing that Elsie, who had slipped down to the steps of the summerhouse, was sound asleep. Suddenly an unexpected bump knocked the little lantern from the governess’s hands, making it fall into Elsie’s lap. She woke with a start.

“A bat! A bat!” cried Miss Barbara, beside herself as she tried to gather up the smashed, extinguished lantern.

Elsie jumped up, not knowing where she was.

“There! There!” screamed Miss Barbara. “On your skirt. The horrible beast fell too, I saw it fall, it’s on you!”

Elsie wasn’t afraid of bats, but she knew that a slight impact can make them dizzy, and they have sharp little teeth to bite you if you try to touch them. Noticing a black spot on her dress, she grabbed it with her handkerchief, saying, “I’ve got it. Calm down, Miss Barbara, I’ve got it all right.”

“Kill it! Smother it, Elsie! Squeeze very hard and smother that horrible spirit, that miserable tutor who’s plaguing me!”

Elsie didn’t understand her governess’s hysteria. She didn’t like to kill, and she thought bats very useful, since they destroy a multitude of mosquitoes and harmful insects. She shook her handkerchief instinctively to let the poor animal escape—but what a surprise, and how frightened she was, to see Mr. Bat escape from the handkerchief and rush at Miss Barbara, as if he wanted to devour her!

Elsie fled across the flower beds, chased by an insurmountable terror. But, after a few minutes, she had second thoughts and went back to help her unfortunate governess. Miss Barbara had disappeared and the bat was flying in circles around the summerhouse.

“My goodness!” cried Elsie hopelessly, “that cruel beast has swallowed my poor fairy! Oh! If only I’d known, I’d have saved her life.”

The bat disappeared and Mr. Bat appeared in front of Elsie.

“My dear child,” he said to her, “it is all well and good to save the lives of the poor persecuted people. Don’t regret a good deed. Miss Barbara is quite all right. Hearing her cry out, I ran over here, thinking one or the other of you was in grave danger. Your governess took refuge in the house and barricaded the door, while showering me with abuse I don’t deserve. Since she abandoned you to what she considers great danger, would you like me to take you to your maid, if you won’t be afraid of me?”

“Really, I’ve never been afraid of you, Mr. Bat,” answered Elsie. “You’re not wicked, but you are very peculiar.”

“Me? Peculiar? Who would make you think I have any kind of peculiarity?”

“But . . . I held you in my handkerchief a minute ago, Mr. Bat, and let me tell you that you risk your life too easily, because, if I had listened to Miss Barbara, it would have been the end of you!”

“Dear Miss Elsie,” answered the tutor, laughing, “I now understand what happened, and I bless you for having saved me from the hatred of that poor fairy, who isn’t wicked either, but who is very much more peculiar than I am!”

After Elsie had had a good night’s sleep, she thought it very unlikely that Mr. Bat had the power to change from man to beast at will. At lunch, she noticed that he gobbled down rare slices of beef with sheer delight, while Miss Barbara had only some tea. She decided the tutor wasn’t the type to treat himself to microscopic insects, and that the governess’s diet was likely to cause hallucinations.