Читать книгу Blue Ravens - Gerald Vizenor - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление› 4 ‹

CARNEGIE TOTEMS

— — — — — — — 1909 — — — — — — —

The Minneapolis Public Library was only ten years old that summer of our migration, a massive stone building with magnificent curved bay windows. The turrets on two corners resembled a baronial river castle, but the books inside were never the reserved property of the nobility.

Andrew Carnegie, the wealthy industrialist and passionate philanthropist, donated more than sixty million dollars to build public libraries, and more to establish schools and universities around the country. A slight portion of his great treasure acquired from the steel industry and other investments was used to construct the Minneapolis Public Library.

Carnegie was a master of steel, stone, railroads, and the great bloom of libraries. More than two thousand libraries were built in his name, but he would not give a dime to build even a bookrack on the White Earth Reservation, our uncle explained, because the federal agents were not reliable and the government would not promise to support the future of books for natives.

Carnegie was a new totem of literacy and sovereignty. The libraries he created were the heart and haven of our native liberty. No federal agents established libraries on reservations, and not many robber barons constructed libraries and universities.

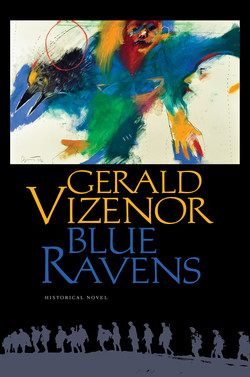

Aloysius painted a huge blue raven, our great new totem of honor and adventure, in one of the turret bay windows of the library. The beak of the raven almost touched the sidewalk and stairs near the entrance. My brother never painted humans, but some of his great ravens traced a sense of character, a cue of human memory. Carnegie was portrayed as a stately blue raven with a bushy mane and great beak in the turret windows.

We could not believe that the books were stacked on open shelves and available to anyone. We walked slowly down the aisles of high cases and touched the books by colors, first the blues, of course, and then the red

and black books. In that curious hush and silence of the library the books were a native sense of presence, our presence, and the spirits of the books were revived by our casual touch. Every book waited in silence to become a totem, a voice, and a new story.

The books waited in silence, waited for readers, and waited for a chance to be carried out of the library. The Last of the Mohicans by James Fenimore Cooper was tilted to the side. The novel was illustrated by Frank T. Merrill, and in one picture a couple with fair skin watched a native wrestle with a bear. The couple was dressed for a dance, and the native wore leather, fringed at the seams, and three feathers on his head. The book waited to be recovered by a reader, but not by me or by my brother. That novel was introduced by our teachers at the government school, along with that nasty poem The Song of Hiawatha by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, but we were never obliged to remember the loopy cultural fantasies of literary explorers. The elaborate frontier of The Last of the Mohicans was a snake oil story.

Augustus teased the reservation native police with the name Chingachgook, and he sometimes used the name Natty Bumppo, both characters in The Last of the Mohicans, in stories about the missionaries and federal agents. So, we had a tricky sense of the characters in the novel by the time our teachers wrote the names on the chalkboard.

Aloysius touched The Call of the Wild by Jack London.

Augustus celebrated our thirteenth birthday with two new books. Our uncle always celebrated our birthdays with books, first picture stories and then literature. The new books were wrapped in the current edition of the Tomahawk. He gave me a copy of The Call of the Wild, and Aloysius received a copy of White Fang. Augustus knew we were inspired by native totems and animal stories, and he knew we would talk about these scenes in the novels. My uncle was a teaser, and he teased and coaxed me to become a creative writer, to create stories of native liberty, and a few years later gave me a copy of Moby-Dick by Herman Melville.

Jack London was a great writer but he was mistaken about dogs and natives. Buck was a natural healer and would never return to the wolves, never in a native story. London was not aware that wolves were native totems, and not the wild enemy.

London made White Fang more human and never understood the native stories of animal healers. The real world of nature that we experienced was always chancy, and sometimes even dangerous, of course, the weather can be dangerous, but not evil and not as violent as the human world. London worried about the animals he had created in an unnatural way, and he might have sent them to some church. The notion of redemption was monotheistic, and that was not natural or native. London was a political adventurist in fiction and never understood native stories, animal totems, or the dream songs of native liberty.

Jack London would not survive on the reservation.

The card catalogue listed every book in the library. Aloysius looked through the cards in the drawer for his name and found a book about Aloysius Bertrand, a French symbolist poet, and Saint Aloysius Gonzaga. Beaulieu was listed many times, a winery in California, and as a reference to a place in France, Beaulieu-sur-Mer, a commune near Nice and Monaco.

The Manabozho Curiosa, that ancient Benedictine manuscript about monks, sex, and animals was not listed in the card catalogue. Naturally, we avoided the word “sex” when we asked the librarian about the Manabozho Curiosa. She had never heard of the manuscript but thought a copy might be found in the Rare Book collection at the University of Minnesota Library.

Aloysius opened several art books on a huge oak reference table and together we brushed the images with our fingers, touched the painted bodies of soldiers, women poised near windows in soft natural light, darker scenes of animals and hunters, and distorted images of humans and houses. Most of the old images portrayed a civilization of pathetic poses and contrition, and the great shadows and slants of divine light by master painters.

The ancient blues were muted.

Yes, the bright flowers, pristine fruit on a table, and exotic birds, seemed at the time to be more authentic than our actual memories and experience of the natural world. The reds, yellows, and greens were bright, the blues faint. The images of exotic birds were realistic studies, an obsession of godly perfection in bright plumage. The painted birds were steady pictures, similar to the portraits of warriors and politicians.

The best of nature, and our sense of nature, was forever in motion by the favor of the seasons. The overnight bruises, creases, crucial flaws caused by the weather, and every wave, ruffle, gesture, and flight were wholesome. The ordinary teases, blush, and blemish of character, were a natural presence, and yet the birds, painted flowers, and fruit that we touched in the giant art books were bright, perfect, ironic, and unsavory.

Ravens would never peck at a pastel peach.

Aloysius slowly backed away from the reference table, looked around the library, and then he painted three blue ravens with massive claws over the modern art images in the books. The wings of the ravens were painted wide and shrouded the table and chairs with feathers.

A young librarian waved a finger and cautioned us not to touch the books. She praised the blue ravens that my brother had painted, and then explained that painting was not permitted in the library. Yes, we pretended to understand the unstated caution, that only the bookable and bankable arts were favored and secured, not the original blue ravens and native totems.

Aloysius painted with two soft brushes and a thick, blunt cedar stick that was roughened on the end. One brush was round, soft, and pointed. The other was a wide watercolor shadow brush. His saliva, and sometimes mine, was used to moisten the blue paste.

Aloysius had made his own paintbrushes. He carved the wooden handles from birch, molded the ferrule sleeve from copper, and the tufts were bundles of squirrel hair for several of his brushes. He used sable hair for the brushes with a fine point.

The new images were much richer and the hues of blue more evocative on the professional art paper. The blue ravens on the newsprint were strong, abstract, and the lines and shadows were in natural motion, never distinct as portraiture, but the ravens were enlivened on the new paper. My brother had created a book of paintings on our first visit to the city.

My first creative impressions were short descriptive scenes, only a few words, more precise than abstract. Every spontaneous scene was more obvious in my memory than in my written words. My original scenes were composed in short distinct sentences, only single images or glimpses of the many scenes in my memory. My words seemed to contain a natural vision of motion, but the actual practices of a writer were not the same as a painter.

My heart is a red raven and rises on the wind.The eyes of nature are in my stories.Cars move with great explosions.Curved windows bend our smiles.Winter is an abstract scene in the autumn.The ice woman is natural reason.City men strut in black coats and tight shoes.Horses wait for motor cars to pass.Books are silent stories.White pine lives in memory.

History is overgrown and chokes the trees.

The sound of a pencil on paper is similar to the sound of a watercolor brush but the words create scenes in the head not the native eye. My written words came together with painted blue ravens in the heart, the intuitive eye, and memory.

Aloysius continued to paint blue ravens in the library reference room. My brother spit in the blue paste and painted grotesque beaks that carried away the pastel fruit, the shadows of librarians at the window, blue soldiers, and the art books.

Gratia Alta Countryman, Head of the Minneapolis Public Library, was summoned to the reference room because my brother would not stop painting. She watched him move the thick brush over the paper, and then she leaned closer as he brushed the blue raven beaks with the softened cedar stick.

Gratia, we learned later, was the very first woman to direct a major city library. She was raised on a farm, graduated from the University of Minnesota, and initiated book stations for laborers and immigrants, and she seemed to appreciate that we were native newcomers in search of adventure and liberty. My brother was the painter, and the stories were mine.

Carnegie was surely impressed with her philosophy of free libraries and enlightened dedication to the public access of books on the shelves. We were impressed that so many books were at hand, and touchable without permission. The books were not concealed, and instantly summoned for review. Books were federal prisoners at the government school.

Gratia rested her heavy hands on the reference table. Her wrists were thick like a native or peasant, her hair was parted on the left, and her narrow nostrils moved with slight traces of breath. She leaned closer to my brother, and with a comic smile asked him to paint a blue raven with a copy in claw of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by Lyman Frank Baum.

Aloysius turned to a new page in his art book, spit in the tin of blue paste, and briskly painted the abstract portrayals of Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman protected by the enormous wings of a blue raven on the reference table. He continued to paint an outline picture of the orphan Dorothy Gale and Toto depicted as a reservation mongrel on the back of a fierce raven with a huge dappled blue beak.

Gratia raised her peasant hands in praise and laughed out loud in the hushed reference room. Several readers turned and stared at the head librarian. The younger librarian was anxious, of course, but she did not raise her finger or comment on the laughter or the saliva and blue paint in the library.

Aloysius had never read The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, but the story of the fantastic adventures were told by several teachers at the government school on the reservation. We resisted the peculiar scenes of wicked cackles and godly virtues because they were not recounted in any native experiences. Stories of the ice woman were much more urgent and memorable. Yet, our slight resistance to the Scarecrow and Tin Woodman must have encouraged the actual memory of the story. So, in a sense the cockeyed wicked scenes became a creative rescue years later at the Minneapolis Public Library. My brother remembered a crude summary of the wizardly story and portrayed the characters in a speedy abstract painting. The head librarian was very impressed by his talent and invited us to her office in the turret with the curved bay windows.

Gratia served milk and cookies, and explained that she was always prepared to serve children treats and books because they are the future readers and patrons of the library. She had established the first reading room for children. Luckily we had entered the main section of the library.

You boys are not children, of course, but we must share the cookies, she said, and turned toward the windows. The reflection of her face was curved and her nose and ears were elongated.

Gratia was apologetic that she had never visited a reservation, but she mentioned Frances Densmore who had studied native songs of the White Earth Reservation. She was surprised to learn that our uncle published a weekly newspaper.

The Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts was located in the library, but the collection of paintings was not open to the public. Aloysius was downhearted that the art collection was not available because that was the primary purpose of our visit to the city. My brother wondered where he could see art, meet artists, and present his blue raven paintings.

Gratia suggested that we visit art galleries to see the work of other painters. She named the Golden Rule Gallery in Saint Paul, and the Beard Art Galleries in Minneapolis. She was certain that we would be inspired by many of the artists who exhibited their work at these galleries. She warned us to be aware that the trendy and new abstract painters were not current or popular in the galleries.

Blue ravens were totemic not mercenary.

Saint Paul was another strange and distant city. The saintly names of missions made sense, but sainted cities were not sensible. Cities were enterprises, sprawling, noisy, and scary places, and not the centers of saints.

The Beard Art Galleries were located on Hennepin Avenue near Lake Street. We boarded the streetcar, sat at the back, and counted the city blocks to the gallery. The conductor pointed to a building on the other side of the street. There, displayed in the bay window of an ordinary storefront were three paintings, a woodland landscape, a bowl of unsavory fruit, and a bright portrait of three Irish setters with feathery tails.

Irish setters were not bound for museums.

Aloysius was worried for the first time about his vision of blue abstract ravens. He had created raven scenes on the train, in parks, on the streets, department stores, hotels, and at the library. The Irish setters and fruit bowl were obstacles to visionary art and he refused to enter the gallery. Suddenly he was distracted and vulnerable in the commercial world of gallery art.

The Irish setters were aristocratic posers, haughty pedigree portrayals, plainly favored over natives and the poorly. So, we walked slowly around the block, and then continued several more blocks west to Lake Calhoun, or the Lake of Loons, which was a native descriptive name. The lake was renamed to honor John Caldwell Calhoun, the senator and vice president. We rested on the grassy lakeshore and created stories about mongrel portraits and landscapes of white pine stumps in the gallery window.

The actual paintings in the gallery window were good copies of a concocted nature, but not abstract native totems or chancy scenes of liberty. We watched the sailboats swerve with the wind and then walked back to the gallery.

Our faces were reflected in the gallery window, and at that very moment a yellow streetcar passed through the scene of our reflection, a throwback to abstraction and native stories. The muted aristocratic setters mingled with passengers on the streetcar. That scene became the most distinctive story of our two days in the city. We told many versions of that story to our relatives. The Irish setters, native faces, and the slow motion of the streetcar that afternoon became a chance union of abstract creation.

The Beard Art Galleries became an abstract scene.

Aloysius pushed open the door with confidence, and we were surprised by the art inside the gallery. There were no bright fruit bowls or setters with feathered tails. The strain of art in the window was deceptive, and we decided that the display was only selected to entice passengers on the streetcars.

The cloudy walls were covered with original art, gouache, oil on canvas, and watercolors on paper, mostly natural water scenes, evocative barns and country houses, railroad stations, sailboats, glorious summer sunsets, autumn maples, and winter landscapes. The trees and outlines were precise images, and the colors were intense and clean. The emigrants who moved to the cities must have been heartened by the romantic and picturesque landscapes.

Three framed distinct watercolors were displayed on sturdy oak easels near the entrance of the gallery. Aloysius moved closer and reached out to touch the magnificent images of misty scenes, and then held back with his hands raised above the easels. The three watercolors, Snowy Winter Road, Summer Afternoon, and Woman in the Garden, seemed to reach out to touch and enchant my brother and me.

Snowy Winter Road was a watercolor of giant trees on a curved country road. The trees were covered with heavy wet snow, a natural bow to the season. The entire scene was muted but the snowy trees, and the morning light, shimmer in the gallery and in my memory.

The Summer Afternoon watercolor was a subtle diffusion of light and the waft and scatter of colors on a sleepy afternoon, a misty secret scene of lacy trees in praise of nature and memory. We could hear the sound of birds and insects in the scene, and the slight glint of dragonflies over the lily pond.

The Japanese Woman in the Garden wore a traditional kimono, and she was crouched near a garden of lilies. We were touched by the subtle motion and magic of the visionary watercolor scenes. The elegant curves were natural, erotic, and magical.

Aloysius was captivated by the Woman in the Garden.

Harmonia, the gallery manager, a lanky, intense woman with short blonde hair pointed directly at my brother, but not at me. She wore a dark gray pinstripe suit, bluish necktie, and black-and-white oxford shoes. Naturally, we were distracted by her manly costume and hardly noticed her severe gestures.

Keep those dirty hands in your pockets, she shouted, and then shooed me toward the door. Aloysius lowered his hands and stared at the manager. She, in turn, folded her arms, raised one long pale blue finger, and stood directly in front of the three easels.

The Irish setter in the window, how much?

The setters are not for sale.

The Woman in the Garden, how much for that watercolor? Aloysius moved behind the easels and read out loud the name of the artist. Yamada Baske, how much for the Japanese Woman in the Garden?

Very expensive, what do you want?

Aloysius told the gallery manager that we wanted to meet the watercolor artist named Yamada Baske. She turned in silence, rocked on her oxfords, and waited for us to leave the gallery.

Aloysius announced that our uncle owned a newspaper, and he would surely buy the Woman in the Garden. Suddenly her manner changed. She cocked her head to the side, smiled, and pretended to be friendly, unaware, of course, that the newspaper was published on the White Earth Reservation. Yamada Baske was Japanese, she said, and he taught art in Minneapolis.

Aloysius revealed that he was a watercolor artist. She smiled and again folded her arms with one finger raised as a gesture of doubt. One of our teachers at the government school raised her finger, but the gesture was more about derision than doubt. My brother opened his art book and presented several of his most recent abstract blue ravens, but not the ones he had painted earlier that day at the library.

Harmonia slowly turned the leaves of his watercolor book, examined each blue raven, and then announced that Yamada Baske, or Fukawa Jin Basuke, was an instructor at the Minneapolis School of Fine Arts. Naturally we were surprised to learn that the art school and the Society of Fine Arts were located on the same floor of the Minneapolis Public Library.

The same conductor was on the return streetcar and asked us about the art gallery. Aloysius told him about the window display, the bright fruit and red setters, and then described the watercolor scene of a beautiful Japanese woman in a garden of lilies.

What does she look like?

Her face was turned to the lilies.

So, why was she beautiful?

The elegance of her hands and feet crouched by the lilies, my brother explained to the conductor, but he was not convinced. We were touched by the mood and subtle hues of the watercolor. The Woman in the Garden was the only picture that was enticing and we wanted to be in the garden scene with that sensuous woman.

Yamada Baske was standing at an easel with a student when we entered the studio. He smiled, bowed his head, and then turned to continue his discussion on the techniques of painting subtle hues of color, traces of reds and blues in watercolors. Baske told the student that the wash of blues was a natural trace of creation, a primal touch of ancient memories. The blues are a procession, he explained, and the turn of blues must be essential, the epitome and trace of natural hues of color.

Aloysius was inspired by the chance discussion of colors, the hues of blue, and once again he flinched and turned shy. My brother was a visionary artist, and that was a native sense of presence not a practice. He had never studied any techniques of watercolor as a painter. So, when he heard an art teacher describe his own natural passion as a painter he became reserved and secretive.

The contrast between visionary, mercenary, and gallery art was not easy to discuss with a learned painter. My brother created blue ravens as new totems, a natural visionary art, and for that reason the scenes he painted were never the same, and are not easily defined as a practice by teachers of art. There were no histories about blue ravens, no learned courses on new native totems. My brother was an original artist, and the images he created would change the notions of native art and the world. His native visions cannot be easily named, described, or compared by curators in art galleries.

Aloysius mounted several of his blue ravens on the empty easels in the studio. Yamada Baske studied the raven pictures from a distance, at first, and then he slowly moved closer to each image on the easels. He described the totemic images as native impressionism, an original style of abstract blue ravens.

Baske was reviewed as an impressionist painter, and exhibition curators observed that he had been trained in the great traditional painting style of the Japanese. Later, in the library, we read that his watercolors conveyed a traditional composition, “but rendered with the airy, misty technique of the impressionists. In some ways this reflects completion of a circle of influence given that the impressionist movement was deeply influenced by Japanese art, particularly watercolors and Ukiyo-e woodblock prints.”

Aloysius created blue ravens, an inspiration of natural scenes and original native totems, and one day his watercolors would be included in the stories told about abstract and impressionist painters. My brother would create the new totems of the natural world in visionary, fierce, and severe scenes.

Baske was truly impressed by the pictures of the blue ravens. He moved from easel to easel, and then mounted more pictures to consider. He commented on the mastery of the blue hues, the subtle traces of motion, the natural stray of watercolor shadows, and the sense of presence in every scene of the ravens.

The blue ravens are glorious, visionary, a natural watercolor creation, said Baske. He raised one hand and waved, a gesture of praise over the blue ravens on the easels, and then he turned to my brother, smiled, and bowed slightly.

Aloysius opened his art book and painted a raven with wings widely spread over the studio easels, misty feathers tousled and astray, beak turned to the side, a blue raven bow of honor and courtesy. My brother presented the watercolor to the artist of the Women in the Garden.

Baske mounted the blue raven on a separate easel. Young man, he said, you perceive the natural motion of ravens, and only by that heart, by that gift of intuition, and distinctive sensibility create the glorious abstracts of impressionistic ravens.

Aloysius was moved by the curious praise, of course, but he was hesitant to show his instant appreciation and sense of wonder. The blue ravens were in natural flight, and the studio was silent. We heard only our heartbeats and the muted screech of streetcars in the distance. The mighty scenes of new totems were gathered on the easels. No one had ever raised the discussion of blue ravens to such a serious level of interpretation or considered the abstract totems with such critical sensitivity.

Aloysius invited the artist to visit our relatives on the White Earth Reservation. Baske smiled, bowed, and accepted the invitation. He walked with us down the stairs to the entrance of the library. Outside he paused, turned to my brother, handed him a tin of rouge watercolor paint, and suggested that he brush only a tiny and faint hue of rouge in the scenes of the blue ravens. Baske told my brother that a slight touch of rouge, a magical hue would enrich the subtle hues of blues and the ravens.

Baske was a master teacher.

My brother painted blue ravens over the train depots on our slow return to the Ogema Station. He practiced the faint touch of rouge, the hue on a wing or in one eye of a blue raven, and a mere trace of rouge in the shadows.