Читать книгу Blue Ravens - Gerald Vizenor - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление› 2 ‹

OGEMA STATION

— — — — — — — 1908 — — — — — — —

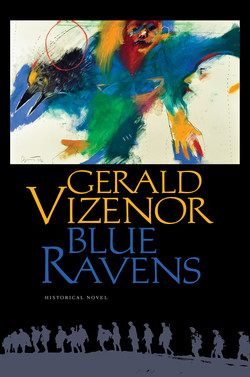

Aloysius painted seven gorgeous blue ravens seated as passengers in a railroad car. The enormous wings of the spectacular ravens stretched out the windows, bright blue feathers flaunted at various angles. The passenger train seemed to be in natural flight that summer afternoon over the peneplain. Great blue beaks were raised high above the windows, a haughty gesture of direction, or a mighty military salute.

The Soo Line Railroad a few years earlier had laid new tracks and built new stations at Mahnomen, Ogema, and Callaway on the White Earth Reservation. The passenger trains arrived twice a day from Winnipeg and Saint Paul. Every afternoon in the summer we heard the steam whistle in the distance, that evocative sound of a new world as the train stopped at the Ogema Station.

Winnipeg, Thief River Falls, Mahnomen, and Waubun were familiar places in one direction of the railroad line. Detroit Lakes, Minneapolis, Chicago, Sault Ste. Marie, and Montreal were not familiar in the other directions. We envisioned many other places, marvelous railroad cities. Places without government teachers, federal agents, mission priests, or reservations.

Blue ravens were our totems of creation and liberty.

Aloysius told the priest that the blue ravens were the only totems that could convey his native vision. No other totems were as secure as the blue raven, not even the traditional crane totem of our ancestors. The stories of native totems were inherited and imagined, but the blue ravens were original and abstract signature totems. My brother created totems as a painter in almost the same way the first totems were imagined by native storiers, by vision, by artistry, but not by the tricky politics of shamans and warriors. The first totems were painted on hide, wood, birch bark, and stone.

The priest would never associate with the creation of native totems. Nature was a separation not an inspiration of holy faith or godly associations. The priest glanced at the blue ravens and then turned away in silence. He seemed to regard the personal creative expressions of my brother as a private and necessary confession or sacrament of penance.

Augustus, our favorite uncle, celebrated the visions of a thirteen year old, or any totemic vision that provoked the priest, and hired us to paint blue ravens and other totems on the outside of the tiny newspaper building. His praise was conditional, as usual, so we returned with our own strategies and agreed to paint the building if he would hire us to sell his newspapers. Our uncle paused to consider our adolescent tactics, and then consented but with more conditions. He would pay only a penny a copy for the newspapers we sold, and we must find new customers and ways to increase the circulation of the reservation weekly.

We painted the newspaper building white a few days later but not decorated with blue ravens. The paint was thick and lumpy, not an impressive cover. The next day we started our first positions as newspaper hawkers, news salesmen with a commission. No one, not even our younger cousins, would work for only a penny a newspaper. The venture, however, was worth much more than the mere penny income.

Augustus was a heavy drinker, at times, and that was both a problem and an advantage. He was more critical of the federal agent when he had been drinking, and that troubled Father Aloysius. Our uncle was always generous when he drank alone or with others, but he seldom remembered promises. One night we easily persuaded our feisty publisher to pay the cost of two train tickets to promote the weekly newspaper at every Soo Line Railroad station between Ogema and the Milwaukee Road Depot in faraway Minneapolis.

The Tomahawk sold for about three cents a copy by annual subscription, and everyone on the reservation who wanted the paper had already subscribed, so we decided to hawk the newspaper to strangers on the train at the Ogema Station. The trains arrived twice a day and we earned about ten cents in a day.

Hawking the Tomahawk was easy because there were no other newspapers published in the area, and because we were directly related to the publisher. I tried to read every issue of the newspaper and to memorize a few paragraphs of the main stories, enough weekly content to shout out the significance of the news stories.

I actually learned how to write by reading the newspapers we sold, by memory of selected descriptive scenes, and by imitation of the standard style of journalism at the time. I learned how to create scenes in words, and to imagine the colors of words, and my brother painted abstract scenes of blue ravens. Most students at our school had learned how to mimic teachers, to recount government scenes, federal agents, and native police, but we were the only students who hawked newspapers with national stories and learned how to write at the same time.

The Progress was the first newspaper published on the White Earth Reservation, and the news was mostly local, including a special personal section on the recent travels, experiences, and events of reservation families. The newspaper reported that our grandmother, for instance, traveled by horse and wagon to visit relatives in the town of Beaulieu. The Progress published reservation news and critical editorials about the ineptitude of federal agents and policies of the federal government.

Major Timothy Sheehan, the federal agent, and native police confiscated the very first edition of the Progress, the newsprint and the actual press, and ordered my relatives to leave the reservation. Agent Sheehan must have thought he was the deputy of a colonial monarchy. Augustus was publisher of the Progress and Theodore Hudon Beaulieu was the editor and printer at the time. The first edition of the Progress, critical of the federal agent and the policies of reservation land allotment, was published on March 25, 1886.

Our relatives refused to leave their homes and newspaper business by the order of a corrupt political agent, and instead sought sanctuary at Saint Benedict’s Mission. Father Aloysius Hermanutz, the mission priest, provided a secure refuge for some of our relatives, and protection from the arbitrary authority of the federal agent. The Episcopal Church had been active in the selection of the agent and dominant in the administration of federal reservation policies. The native police had refused to arrest or remove our relatives from the reservation.

The obvious constitutional issue of freedom of the press was decided a year later by a federal court. The court ruled in favor of my relatives, who had a right to publish a newspaper on the reservation, or anywhere in the country, without the consent of a federal agent. The native and constitutional rights of my relatives and other citizens were restored on the White Earth Reservation. The second edition of the Progress was published on October 8, 1887.

Augustus Beaulieu changed the name of the weekly newspaper to the Tomahawk in the early nineteen hundreds, and the content of the newspaper changed, along with the name, from local reservation stories and editorials to national and international news reports. The readers must have wondered what happened to the local stories, and at the same time marveled at the publication of national news stories. Straightaway the reservation became a new cosmopolitan culture of national and international news.

White Earth became a cosmopolitan community.

The readers of the Tomahawk could not understand how the publisher was able to gather so much news from around the world every week. The national news was seldom timely, never daily, but the readers were not concerned because most stories on the reservation were seasonal. Sometimes national stories were read a month or two later as current events, and in this way national news was always current on the reservation. The sense of time was created by native stories, not in the urgent political reports of newspapers. Later, the Tomahawk published on the first page regular editorial and news stories and by Carlos Montezuma, or Wassaja, one of the first native medical doctors.

We learned much later that natives on the reservation were more literate than the general population of new immigrants, and natives read more newspapers because the federal government established schools on reservations. Federal assimilation policies forced most native children to learn how to read and write long before national compulsory education. We were required to attend the government school on the reservation, and too many native students were sent away to boarding schools.

Augustus subscribed to preprinted or patent inside newspaper pages, the actual pages were printed somewhere else and delivered to the reservation for publication. Theodore Beaulieu, once the actual printer and editor of the Progress, was superseded by the patent inside pages of the Tomahawk. Many newspapers were published around the country with the same patent stories of national and international news reports and advertisements. The pages of the patent inside were selected editorial tours of world news, not local native issues or reservation rumors, but a parcel of disaster reports and other stories from obscure and marvelous places.

“Everyone knows the strange old stories of the reservation,” our uncle declared. “The Tomahawk needs new strange stories, and the newer and stranger the outside stories the better for reservation readers.”

Augustus was right, but in time we became better at creating our own strange native stories of the reservation than hawking the content of some faraway story by a writer who constructed the news of the world for hundreds of weekly newspapers. The patent inside pages displayed national advertisements. Mostly the advertisements were for fast medicine cures. Some blank sections of the newspaper were reserved for local promotions.

“Paxtine Toilet Antiseptic for Women” was a regular patent advertisement in the Tomahawk, but the use of a douche remained a mystery. We were callow about the need and the actual usage, so we never hawked the douche promotion to women at the Ogema Station. We were not hesitant, however, to declare the news, wave our newspapers, and shout out about other advertisements.

“Ladies can wear shoes one size smaller after using Allen’s Footease, a certain cure for swollen, sweating, hot, aching feet.” We never sold one paper with that announcement, so we learned to hawk discreet news and to avoid any laughable promotions of patent medicine cures.

The Hotel Leecy, the largest and “most commodious hotel” on the reservation, was advertised on a side column in almost every issue of the Tomahawk. The hotel served daily communal meals with seasonal fish, game, and vegetables, and provided a livery stable. John Leecy, the proprietor, allowed us to ride free on the horse carriage between the hotel and the train station because we always promoted the hotel to arriving passengers. Leecy admired our ambition and hired us a few months later to feed and groom horses in the hotel livery stable.

Aloysius painted two blue ravens perched on the back of a roan stallion owned by John Spratt. Two years later he invited us to work in his harness shop. That was a very good job at the time, one of the best, because we continued to care for horses and at the same time learned about the harness business. We learned how to forge and fashion metal, but later we returned to work in the livery stable at the Hotel Leecy. Daily we encountered travelers and government bureaucrats who stayed at the hotel, and every visitor talked with us about horses and the future. No one ever talked to us about the forged parts of a harness. The blue ravens my brother painted and my tricky stories would become the crucial totems and portraits of our future service in the First World War.

The Leecy, Hiawatha, and Headquarters were the only hotels on the reservation, and there was a summer boarding house in the community of Beaulieu. Louis Brisbois, the proprietor of the Hotel Headquarters, rented clean rooms, according to the newspaper advertisements, and the “tables are always provided with fish, game and vegetables in their season.” Aloysius sold Brisbois a blue raven perched on the peak of the hotel, and he invited us to work in the kitchen for food and money. The invitation was very tempting, the food and pay, but we were more interested in horses at the time, and naturally we were loyal to our uncle and to John Leecy.

The Pioneer Store, established by Robert Fairbanks, and many other merchants and traders in groceries, lumber, and sundries, advertised in every issue of the Tomahawk. The Motion Picture Theater, the first and only theater on the reservation, was promoted on the back page of the newspaper. Movies were shown twice a week. The tickets cost ten cents on Tuesday and twenty cents on Saturday.

Augustus treated us to our first movie, short scenes about trains and cowboys, but the tiny theater was musty, crowded, and the actors were crude and dopey. The cost of a single movie ticket was about the total income for a day of newspaper sales at the station, so we saved our money to travel on the Soo Line Railroad to Winnipeg, Minneapolis, or Montreal.

I started to write scenes and stories that summer, and imitated the newspaper style of the patent insides. Later, the government teachers corrected my style, and they would not believe the sources of my literary inspiration. My first written scenes were tightly packed with descriptive, imitative, derivative images and analogies. Most of my scenes were not yet original expressions or even creative enough to be considered unintended irony or mockery.

Aloysius painted blue ravens posed as the engineer of the train, as haughty passengers, and enormous ravens seated in the caboose, perched on the water tower, and blue ravens waiting at the station. Later he painted ravens with blue bluchers, blue women with raven beaks, and the station agent with blue wings. I wanted to write in the same way that he painted.

Together we sold an average of ten copies of the Tomahawk two or three times a week at the Ogema Station. We earned a total of about thirty cents a week, and after three months of hawking the newspaper that summer at the station we had earned less than two dollars each. Not enough to buy two train tickets to Winnipeg or Minneapolis.

The Feast of Good Cheer was our deliverance.

Aloysius sold several portrayals of blue ravens on newsprint but together we sold only four copies of the Tomahawk to relatives at the fortieth anniversary of the treaty settlement of the White Earth Reservation on May 25, 1908. Naturally there were pony races and music by the native White Earth Band. Augustus raised his whiskey bottle and praised our success as hawkers of his newspaper. We smoked a peace pipe for the first time that summer at the reservation anniversary, and we ate with the adults at the Feast of Good Cheer.

Soo Line Railroad tickets were more expensive than the cost of travel on the old Red River Oxcart Trail that ran four hundred miles from Winnipeg or the Selkirk Settlement through the reservation near the trading post at Beaulieu and White Earth to Detroit Lakes and the final destination in Saint Paul, Minnesota.

The deep ruts of the oxcart wheels were evident on the entire route north to south across the reservation. Aloysius was always ready for an adventure. We were eight years old the first time we walked several miles in the old wagon ruts on our way to another world. The weather turned out to be the adventure, however, not the route of the oxcarts. A severe thunderstorm, lightning, thunder, and heavy rain, changed the rutted course of our adventure to rivers. We took cover under a huge white pine and waited for the storm to pass. The oxcart wagon ruts overflowed, natural tributaries of an obsolete time, and our great adventure ended with stories of a memorable thunderstorm.

The new railroad, station, and the weekly newspaper became our sense of the future, although later we actually earned more money mucking out the livery stable at the Hotel Leecy. Yes, at the time the muck of horses provided a better salary than hawking newspapers with patent cosmopolitan news stories about the nation and the world.

Aloysius painted two solemn blue ravens seated on a bench at the railroad station in Mahnomen. The huge beaks of the ravens were covered with dark blue spots. A copy of the Tomahawk was on the bench next to the blue ravens. The banner headline was a single word, SMALLPOX. Wisely we never hawked that scary headline of the newspaper, and there was no reason to reveal the actual story that smallpox had been reported at Munroe House in Mahnomen. The Minnesota Board of Health had released the same report that “smallpox was increasing” in the state.

That afternoon we announced instead that the “Japanese landed more than thirty thousand troops in Wonsan, Korea,” and expected to “advance on Vladivostok” in Russia. We sold three papers with that headline, and four more copies with the report that “annuities due under the old treaties will be paid to the Mississippi and Lake Superior bands by Agent Michelet.” The annuity payments started on Monday, May 29, 1908, and each person received $8.40 in cash. Naturally our families were there for the carnival of treaty payments. Our relatives danced and told stories about the fantastic new worlds of railroads and automobiles.

The Great White Fleet was news that week in the Tomahawk so we hawked the story at the station. President Theodore Roosevelt had ordered the fleet to sail around the world for about two years to demonstrate the naval power and mastery of the United States. The great fleet left San Francisco on July 7, 1908. Not one paper was sold in the name of the ironic pale peace voyage.

Aloysius painted blue ravens on the mast of ships and named the Great White Fleet the Great Blue Peace Fleet. The chalky color code of the fleet was an obvious contradiction of sentiments. The color of peace was not the same as the notion of naval power. The Blue Fleet would have been a more humane and enlightened color in Australia, New Zealand, Philippine Islands, Brazil, Chile, Peru, and San Francisco. The blue ravens represented a greater sense of peace than the voyage of dominance around the world by sixteen white battleships of the United States Navy.

William Jennings Bryan was nominated for president at the Democratic National Convention that summer in Denver. Clearly there was no need to shout out that story because the mere mention of his name sold nine copies of the Tomahawk, more than any other person, place, scandal, or political story. Bryan ran three times for the presidency. He never won the electorate but he was greatly admired by natives on the White Earth Reservation.

The next train arrived later that afternoon from Winnipeg and we hawked the newspaper story about an absurd prison sentence. Emma Goldman, considered the antichrist of anarchism, touched the very hand of an army private and that single touch became news around the world. The private was sentenced to five years in prison. The train passengers were apparently not interested in the story and turned away. We hawked the name of Emma Goldman down the aisle of the passenger car but the ironic news of a soldier and the touch of a great anarchist was not good enough to read on the train.

The passengers were particular about news stories, and the greater the stories of shame, coincidence, and native victimry the more newspapers we sold at the station. The travelers wanted to read about adventures, crime, war, storms, cultural turndowns, political corruption and rebuffs, and the ironic survival of ordinary people.

These newspaper stories about public experiences were our best tutors. I imagined these scenes later and created my own ironic stories. We were persistent, persuasive, and pretended to be at the very center of the worldly stories that were published that summer in the Tomahawk.

The Ogema Station was built near the grain elevator at the very edge of the woodland and the peneplain. The new station faced west, warmed by the winter sun, but in the summer the platform was not shaded. The Soo Line Railroad provided a residence for the agent and his family in the two-story station. The observation site and ticket office were located in the bay window near the main tracks, and a second building to store freight was attached to the side of the station. The railway mail and “wish book” catalogue orders were stored in the freight house. Montgomery Ward shipped the famous Clipper steel windmills to farmers. Many years later several houses, the entire precut materials, planks, windows, doors, siding and shingles, were ordered by mail from Sears, Roebuck and Company catalogue and shipped by train to the Ogema Station.

The station agent was a stout, silent, serious man who sat in the bay window and waited for the next train from Detroit Lakes or from Winnipeg. He encouraged and protected our newspaper business and allowed us to board the trains to hawk copies of the Tomahawk to passengers. The sound of his whistle was absolute and we never abused his trust. His wife provided water on hot summer days, and sometimes she would make sandwiches. The station agent, his wife, and our mother were very close friends. They had once lived near Bad Medicine Lake.

The Mogul engine sounded the whistle and came to a slow stop at the station. The building and platform shuddered from the weight and coal-fired rage of the mighty engine. Steam shrouded the station windows. We waited inside to avoid the heat. Patch, the assistant agent, a smartly dressed native in uniform, greeted every passenger with a salute. He wore gray work gloves and his military coat was properly buttoned, even in the heat and humidity of the summer.

Patch Zhimaaganish, our good friend, was not paid for his service and dedication, but the station agent was sympathetic and allowed him to practice the manner and courtesy of a railroad conductor. Patch was the only boy to survive in his family, and so his given name was a tease of fate. The translation of his surname was “soldier” in the language of the Anishinaabe. His mother tailored a dark brown uniform for him with bright brass buttons and told her son to find a future on the railroad. So, he reported early every day to the station agent and proudly carried out his unpaid railroad duties with dignity.

Patch was taught to play the bugle by his grandfather who served as a bugler in the Civil War. His grandfather was badly wounded, lost a leg, and was given the nickname zhimaaganish, or soldier, when he returned from the war. That nickname became a surname when the reservation was created by treaty in 1868.

Patch Zhimaaganish was an ecstatic singer with a rich baritone voice. The government teachers praised the soldier but the students only mocked his manly voice. He sang native dream songs when the trains arrived at the station, and sometimes he sang in the rain and to the sunset. The Soo Line Railroad agents at other stations on the line told passengers to listen for the great voice of the young agent at the Ogema Station. Patch was honored for his voice, dream songs, and for his courtesy.

In the skyI am walkingA birdI accompany.The first to comeI am calledAmong the birdsI bring the rain

Crow is my name.

Aloysius painted an abstract portrayal of a soldier in uniform, and with two blue ravens at his side. The ravens with enormous beaks pecked at the bugle and buttons on his coat. Patch never had a father or a brother, so he was grateful for our attention and especially for the picture of the blue ravens. The students at the government school teased him as a stupid student, and more so in uniform, and gave him a new nickname, “Niswi S,” or “Triple S,” for Simple Simon Soldier.

Patch Zhimaaganish was a dedicated volunteer conductor at the station, a singer, bugler, and the soldier of his name. We became close friends that summer because he served the railroad agent and we hawked newspapers to passengers at the Ogema Station. Later we were mustered together and served as soldiers in the First World War in France.