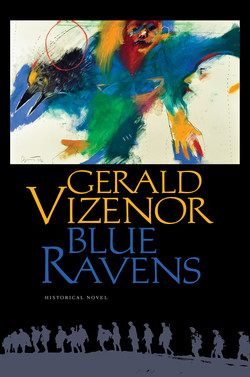

Читать книгу Blue Ravens - Gerald Vizenor - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление› 1 ‹

ROMAN BEAKS

— — — — — — — 1907 — — — — — — —

Aloysius Hudon Beaulieu created marvelous blue ravens that stormy summer. He painted blue ravens over the mission church, blue ravens in the clouds, celestial blue ravens with tousled manes perched on the crossbeams of the new telegraph poles near the post office, and two grotesque blue ravens cocked as mighty sentries on the stone gateway to the hospital on the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota.

My brother was twelve years old when he first painted the visionary blue ravens on flimsy newsprint. Aloysius was truly an inspired artist, not a student painter. He enfolded the ethereal blue ravens in newsprint and printed his first saintly name on the corner of the creased paper.

Aloysius Beaulieu, or beau lieu, means a beautiful place in French. That fur-trade surname became our union of ironic stories, necessary art, and our native liberty. Henri Matisse, we discovered later, painted the Nu Bleu, Souvenir de Biskra, or the Blue Nude, that same humid and gusty summer in France.

The blue ravens were traces of visions and original abstract totems, the chance associations of native memories in the natural world. Aloysius was teased and admired at the same time for his distinctive images of ravens.

Frances Densmore, the famous ethnomusicologist, attended the annual native celebration and must have seen the visionary totemic blue ravens that summer on the reservation. Her academic studies were more dedicated, however, to the mature traditions and practiced presentations of art and music than the inspirations of a precocious native artist.

President Theodore Roosevelt, that same year, proposed the Hague Convention. The international limitation of armaments was not sustained by the great powers because several nations united with Germany and vetoed the convention on military arms. The First World War started seven years later, and that wicked crusade would change our world forever.

Marc Chagall and my brother would be celebrated for their blue scenes and visionary portrayals. Chagall painted blue dreams, lovers, angels, violinists, donkeys, cities, and circus scenes. He was six years older than my brother, and they both created blue visionary creatures and communal scenes. Chagall declared his vision as an artist in Vitebsk on the Pale of Settlement in Imperial Russia. Aloysius created his glorious blue ravens about the same time on the Pale of White Earth in Minnesota. He painted blue ravens in new reservation scenes perched over the government school, the mission, hospital, cemetery, and icehouses. Many years later he blued the bloody and desolate battlefields of the First World War in France.

Chagall and my brother were the saints of blues.

Aloysius was commended for his godly native talents and artistic portrayals by Father Aloysius Hermanutz, his namesake and the resident priest at Saint Benedict’s Mission. Nonetheless the priest provided my brother with black paint to correct the primary color of the blue ravens. The priest was constrained by holy black and white, the monastic and melancholy scenes and stories of the saints. Black was an absence, austere and tragic. The blues were totemic and a rush of presence. The solemn chase of black has no tease or sentiment. Black absorbed the spirit of natives, the light and motion of shadows. Ravens are blue, the lush sheen of blues in a rainbow, and the transparent blues that shimmer on a spider web in the morning rain. Blues are ironic, the tease of natural light. The night is blue

not black.

Augustus Hudon Beaulieu, our cunning and ambitious uncle, overly praised my brother and encouraged his original artistry. Our determined uncle would have painted blue the entire mission, the face of the priest, earnest sisters, the government school and agents. He had provoked the arbitrary authority of federal agents from the very start of the reservation, and continued his denunciations in every conversation. Our uncle easily provided the newsprint for the blue ravens because he was the independent publisher of the Tomahawk, a weekly newspaper on the White Earth Reservation.

Aloysius never painted any images for the priest, black or blue, or for the mission, and he bravely declined the invitation to decorate the newspaper building with totemic portrayals of blue bears, cranes, and ravens. He understood by intuition that our uncle and the priest would exact familiar representations of creatures, and that would dishearten the natural inspiration of any artist who created a visionary sense of native presence. My brother would never paint to promote newspapers or the papacy.

Blue ravens roost on the fusty monuments.

Aloysius was actually a family stray, but he was never an orphan or outcast in the community. He had been abandoned at birth, a newborn ditched at the black mission gate with no name, note, or trace of paternity. My mother secretly raised us as natural brothers because we were born on the same day, October 22, 1895.

We were born in a world of crucial missions unaware of the Mauve Decade and the Gilded Age and yet we created our own era of Blue Ravens on the White Earth Reservation. That same year of our birth Captain Alfred Dreyfus was unjustly convicted of treason and dishonored as an artillery officer in France, and Auguste and Louis Lumière set in motion the cinematograph and screened films for the first time at Le Salon Indien du Grand Café at the Place de l’Opéra in Paris.

Two Benedictine Sisters, Philomene Ketten and Lioba Braun, embraced the forsaken child at the mission gate and named him in honor of the compassionate priest. Aloysius was my brother by heart and memory, by native sentiment, and our loyalty was earned by natural scares, and covert confidence, always more secure as brothers in arms than by the mere count and conceit of our paternal blood descent.

Father Aloysius was solemn and solicitous in the presence of the boy who would bear his first name, and the name of a saint. The priest was an honorable servant, and he was much adored by the native parishioners of the reservation mission. Yet, to appreciate his consecrated name in the dark eyes of a forsaken native child would never be the same as a ceremonial epithet on a monument or holy façade.

My mother was not pleased that her second son, my brother by chance, was named in honor of the priest. She respected the priest, the dedication of the sisters, and the mission, but she considered the name too much of a burden on the reservation. The situational caution of that priestly name was soon alleviated, however, when my aunt named her son, born a year earlier, Ignatius. The priestly name was delayed because he was not expected to survive the year. Only then were the honorable namesakes of two priests and two saints acceptable to the mission and to our native families.

Aloysius was never an easy name to pronounce. The teases and ridicule of his saintly name were constant at the government school, such as, Alley boy, wild son of the mission priest. Mostly the parents of the teasers were members of the Episcopal Church and dedicated critics of the Catholic Mission. Aloysius practiced the artifice of silence and the politics of evasion, similar to the rehearsal of a wise poker player, and he studied the strategies of counter teases. He would pause, turn aside, and declare, “Mostly, the son of tricky saints.” Only the priest, the sisters, and my parents knew that my brother had been abandoned at the mission.

Aloysius was delivered a second time, in a sense, a few days later at our house near Mission Lake. My mother raised us as twins, nurtured us as a timely union, and taught us to perceive the natural motion of the seasons, and the subtle hues of color in nature. She was an artist at heart and might have painted her children blue and united in flight over the reservation. Those early insights and memories were the start of my natural sense of creation stories and family. We were not the same, of course, natives and brothers are never the same, but we became intimate and loyal friends by experience and confidence. We were driven by the same intense curiosity, by a sense of empathy, wonder, the natural surprise of intuition, and always by the tender tease of our mother. She experienced the world through our adventures, and so she teased every scene, gesture, pose, and story.

Our parents were born near Bad Medicine Lake, north of Pine Point and west of Lake Itasca, the source of gichiziibi, the Great River, or the Mississippi River. Many generations before the treaty reservation two great native families, and only two, lived on the north and south shores of Bad Medicine Lake.

Bigiwizigan, or Maple Taffy, the ironic nickname of a dubious native shaman, created stories of mistrust about Bad Medicine Lake because there was no obvious source of the water. The cunning shaman used the mystery of the lake to sway his stories of unease and medicine mastery.

Bad Medicine, about five miles long, was cold and crystal clear, and the sources of water were natural springs. Our native ancestors created by natural reason the obvious origin stories of the water, and were secure on the north and south shore, the only native families who dared to live near the lake.

Honoré Hudon Beaulieu, our father, was born on the north shore of Bad Medicine Lake. He was also known as Frenchy. Our mother was born on the south shore of the lake. These two families, descendants of natives and fur traders, shared the resources of the lake and pine forests. My father was private, cautious, but not reticent. He was native by natural reason and disregarded the federal treaty that established the White Earth Reservation. Honoré refused to honor the boundaries and continued to hunt, trap, fish, gather wild rice and maple syrup in the manner of his ancestors.

Honoré shunned the federal agents.

Margaret, our mother, was carried in a dikinaagan, or native cradleboard, and remembers the scent and stories of maple syrup. The two families of the lake came together several times a year to share the labor and stories of gathering wild rice and making maple sugar. Our parents met many times at wild rice and sugar camps. More natives were conceived at sugar camps than any other place.

Honoré was a singer and woodland storier, and in his time created scenes about resistance to federal agents and the native police. He refused to relocate and shunned the summons to receive an assigned allotment of land according to the new policies of the federal government. He was a fur trade hunter and never accepted or obeyed any government. My father continued to hunt, fish, and cut timber near Waabigan, Juggler, and Kneebone lakes, as his ancestors had done for many centuries.

Honoré had earned the veneration of many natives for his resistance to the government, and for his integrity as an independent hunter and trapper. Politicians and federal agents cursed his name, and yet they had never visited or heard his stories. The native police ordered and threatened him several times, but only our mother and the contract of a timber company convinced him to accept an allotment. Our father never located the actual land that was allotted in his name, an arbitrary transaction, but he agreed to move with his pregnant wife to a new house near Mission Lake, and at the same time he was hired by a timber company to cut white pine near Bad Medicine Lake.

The federal agent selected the new teachers at the government school. Most of the teachers were from Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts in New England. The agent never hired a native teacher. He always wore a black suit, and the teachers were secured in layers of white muslin with creamy flowers. The classroom was unnatural, a drafty box of distractions, the pitch and duty of an awkward hem and haw civilization. The teachers roamed and droned for hours at the chalkboards. The autumn wind soughed with the stories of native shamans in the corridors. Native word players cracked in the cold beams, and the ice woman moaned at the frosted windows. The ice woman murmured seductive stories to lonesome natives in winter, and we were the lonesome ones in school. She whispered a temptation to rest in the snow on the long walk home at night. She gathered the souls of those who were enticed by her treachery.

The ice woman was a better story than the presidents.

Every winter day we cracked and moved the thick clear chunks of ice on the schoolroom windows, and pretended to melt the ice woman and other concocted beasts and enemies of natives by warm breath, touch, and natural motion on the windowpane. Sometimes we told stories that the government teacher was the ice woman but we never dared tease her to rest overnight in the snow. Actually we never mentioned the name of the ice woman. Our stories were only about the natives who had been tempted by the ice woman and froze to death.

The federal agent ridiculed the ice woman stories and blamed the deaths on alcohol. Only the clumsy son of the assistant agent dared to name the teacher as the ice woman. He knew nothing about native stories of shamans or the ice woman. We turned away and shunned the stupid student because natives needed the most creative stories of the ice woman to survive the winter, and we needed even better stories to survive the federal agents and barrels of commodity salt pork.

Summer in the spring was our natural liberty.

The only memorable experience on the reservation was nature, the rush of the seasons, summer in the early spring, the fierce autumn wind out of the western prairie, the gusts and whispers in the mighty forests of white pine. Our every moment outside of school was a sense of fugitive adventures. We shared the notions of chance, totemic connections, and the tricky stories of our natural transience in the world. We were delivered by stories, and our best stories were nothing more than the chance of remembrance. My brother was delivered by chance, we learned years later, and that clearly demonstrated our confidence in stories of coincidence and fortuity.

Margaret, our mother, never revealed the mission secret that my brother was a reservation stray, a newborn of obscure paternity, and apparently that we were not related by blood, until that early summer when we were drafted and departed by train for military service in the American Expeditionary Forces in France.

Our mother was a herbal healer and insisted that her son the artist use only natural paint colors. She provided the natural blue tints that my brother used to paint ravens. Blue was not a common native pigment, so the blue ravens were doubly distinctive. The pale blue tints were made with crushed plum, blue berries, or the roots of red cedar. My mother boiled decomposed maple stumps and included fine dust of various soft stones to concoct the rich darker hues of blue and purple. The synthetic ultramarine powder from traders was not suitable for painting.

Most of the blue ravens were abstract, with huge dark blue angular beaks and almost human eyes. The curves of the wings were broken in flight, and several feathers were painted with elaborate details. Some ravens were turned upside down in flight, as ravens turn over, cant, bounce, and play in flight with other ravens over the mission and post office.

My brother painted blue ravens as sentries at the stone gate of the hospital, and that troubled the priest more than a naked woman, even more than the stories that my brother was the son of the priest. The giant claws of the abstract raven were painted dark blue, with faint veins and the broad traces of human hands. Two claws were curved with cracked fingernails. The two blue sentry ravens wore masks. The huge beaks were outlined and distorted, and turned to the side of the ravens.

Aloysius truly painted abstract scenes by inspiration not by mere duplication or representation, and yet the priest was concerned that he had painted the images of demons in the ravens. My brother had never seen the haunting images of raven masks with monstrous beaks worn by medical doctors during the Black Plague in Europe.

Aloysius was curious, of course, but my brother had already established his own expressionistic form and style, abstract blue ravens in the natural world, and the chance associations of material scenes in cities. Later he had created blue ravens of war, and he would continue to create his inspired scenes of blue ravens over the parks, statues, and bridges over the River Seine in Paris.

No one on the reservation would have associated the abstract blue ravens with the modern art movements of impressionism or expressionism, or the avant-garde, and certainly not compared the color and style of the inspired raven scenes on the reservation with the controversial painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon by Pablo Picasso. Yet, my brother painted by inspiration the original abstract blue ravens at the same time that Picasso created The Brothel of Avignon, the translated title, in 1907. Picasso was swayed by the notion of primitive scenes. The five naked women were pitched to the viewer, angular, gawky, excessive, abstract, and two women wore masks, the obvious influence and deliberate conceptual imitation of primitive art that had been exhibited at the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris.

Aloysius accepted the crown of chance, an uncertain destiny and saintly name, and became a soldier and artist in the American Expeditionary Forces in France. We served together as scouts in the same division and infantry regiment, and survived the unbearable memories of shattered blue faces in the brush, broken bodies, small bare bones in the muck, and solitary tremors of hands and hearts in the ruins of war. The eyes of soldiers at the end turned hoary with no trace of rage, sense of solemn touch, shimmer of blood, or praise of irony.

We were brothers on the reservation, brothers in the bloody blue muck of the trenches, slow black rivers, brick shambles of farms and cities, brothers of the untold dead at gruesome stations. Bodies were stacked by the day for a wretched roadside funeral in the forest ruins. We were steadfast brothers on the road of lonesome warriors, a native artist and writer ready to transmute the desolation of war with blue ravens and poetic scenes of a scary civilization and native liberty.

››› ‹‹‹

The Italian Aloysius of Gonzaga, a sixteenth-century saint, was castle born and encouraged by his mighty father to become a soldier. He was a warrior only in name. Aloysius the original renounced his inheritance to become a priest and vowed chastity, poverty, and obedience, a comely ritual of conceit, monotheistic separation, and ancestral agony.

Father Aloysius Hermanutz was born in the ancient Kingdom of Württemberg in 1853. He studied to become a Benedictine priest and dedicated his godly service and obedience to the care, conversion, and education of natives for some fifty years at Saint Benedict’s Mission on the White Earth Reservation. Aloysius, my brother, continues his saintly name in the marvelous artistry of a painter, not in the doctrines of monotheism, obedience, and the noticeable pain of priestly courtesy.

Saint Aloysius envisioned his own death at age twenty-three on June 21, 1591. Aloysius Hudon Beaulieu was drafted with me and other native relatives at the very same age and in the same month some three centuries later as ordinary infantry soldiers of the American Expeditionary Forces in the First World War.

The chance connections of soldiers and saints.

Ignatius Vizenor and many of our other cousins enlisted or were drafted that same summer to serve as soldiers in the ironic name of the Great War. Ignatius was the namesake of Father Ignatius Tomazin, and more notably of Saint Ignatius of Loyola.

Ignatius, our cousin, was the firstborn of Michael and Angeline Vizenor. He was raised with four brothers and two sisters. Joseph, the last born, was elected many years later as the manager of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe in Minnesota. Ignatius and his brother Lawrence, who was a year younger, were privates in the American Expeditionary Forces in France.

The Beaulieu and Vizenor families praised and raised large godly families, a legacy of the fur trade and that premier native union with spirited descendants of New France. The families were mostly devout but they became cautious Roman Catholics after the First World War and the Great Depression. Absolute devotion to a church or a saint was more uncertain after the massive death and destruction of an unspeakable world war and the absolute desperation of extreme poverty.

Many native fur trade families came together with new and obscure traditions, the union of blood and treasure to honor and defend France. A disproportionate number of natives enlisted and others were drafted to serve in the military, and their reservation families invested in patriotic war bonds to cover the cost of the American Expeditionary Forces.

Peter Vizenor, or Vezina, and Sophia Trotterchaud raised fourteen children, including Abraham, Henry, and Michael who married Angeline Cogger. Peter was a native hunter and fur trader at the time the reservation was established in 1868. Two of their children married and raised twenty more children. Abraham Vizenor and Margaret Fairbanks, for instance, raised five boys and six girls on the reservation. Henry Vizenor and Alice Mary Beaulieu raised nine children on the reservation and then the family moved to Minneapolis at the end of the Great Depression.

Clement Hudon Beaulieu and Elizabeth Farling raised ten children and were removed by the federal government from Old Crow Wing to the new White Earth Reservation. Augustus Hudon Beaulieu, the firstborn, founded and was publisher of the Progress, and later the Tomahawk, the first weekly newspapers published on the reservation. Clement Hudon Beaulieu, the eighth child and namesake of his father, became a priest in the Episcopal Church. Charles Hudon Beaulieu served in the Civil War and was promoted from private to captain in the Ninth Minnesota Volunteers. Theodore Basile Beaulieu, the youngest of the ten children, married three times and raised six children with his first wife Anne Charette, two children with his second wife Maggie Pemberton, and four children with his third wife Anna Tanner.

These first native families of the fur trade and the reservation begot a new nation, and their sons and daughters served with honor and distinction in every war elected, concocted, and declared by politicians in two centuries. Most native soldiers were born on federal reservations, served with others in integrated companies, and were not yet recognized as citizens at the time of the First World War. Natives of the fur trade served to save one of the nations of their ancestors. France established many war memorials, but never a memorial to honor the natives of the fur trade.

Ignatius of Loyola was the mastermind of the Society of Jesus, otherwise named the Jesuits. Basque born more than four centuries ago he waived nobility, his knightly fortune, and by vows of poverty and chastity became a hermit, priest, and theologian. Ignatius was inspired by many reported visions of the saints, sacred adventures, and holy figures, and these marvelous ethereal contests in his dreams determined the stories of his divine service. He was canonized and declared the patron saint of soldiers.

Ignatius Vizenor was never secure with a saintly name.

Father Ignatius Tomazin was the first priest delegated by the abbot of Saint John’s Abbey to establish a mission at the White Earth Reservation. Federal policy at the time favored the mercy and politics of the Episcopal Church over the secretive papacy of Rome. Father Tomazin was a testy immigrant from Ljubljana, Slovenia, with a great vision of political resistance, and he spoke the language of the native Anishinaabe. He was provoked and criticized by Lewis Stowe, the nasty federal agent, who had been appointed by the Episcopal bishop Henry Benjamin Whipple. Stowe was actually the agent of the bishop, not the federal government, and he maligned Father Tomazin.

The Catholic natives on the reservation defended the mission priest and united to resist the arbitrary authority of the agent and the policies of the federal government to designate a minority religious functionary.

Father Ignatius Tomazin, in February 1879, accompanied a delegation of five principal native leaders, Wabanquot, or White Cloud, the head chief, Mashakegeshig, Munedowu, Shawbaskung, and Hole in the Day, the younger, to discuss the crucial issues of native liberty on the White Earth Reservation with federal officials in Washington.

Father Tomazin was eventually removed from the White Earth Reservation because he rightly goaded the federal agents and chosen Episcopalians. The feisty priest protected native political liberty. Some thirty years later he served as the pastor of a church in Albany, Minnesota. Tragically the nasty parishioners of that mingy and disagreeable community challenged the priest, beat and cursed him in the parish house, and chased him out of town. Father Tomazin, then in his seventies, was badly wounded in spirit, and deceived by his own resistance, wandered to Chicago and “jumped to his death from the sixth floor of a hotel,” according to the New York Times, August 27, 1916.

Ignatius, our coy, courteous, and elegant cousin would not survive the saintly names or priestly patronage. He was born premature, so tiny as an infant that he was swaddled in an ordinary cigar box. Partly to overcome the constant teases and tedious stories of his hasty birth and chancy presence he became a fancy dresser on the reservation. He wore smart suits, ties, and a dark fedora, but his courage and costumes were not enough to survive the horror of the First World War. Ignatius was killed in action on October 8, 1918, at Montbréhain, France, and buried in Saint Benedict’s Cemetery on the White Earth Reservation.

››› ‹‹‹

Aloysius revealed his visions in the creative portrayals of blue ravens, and the abstract ravens became his singular totem of the natural world. He was convinced that his totemic associations were original, and there were no other blue raven totems or cultures in the world.

Aloysius forever soared with ravens and never wholly returned to the ordinary world of priests, missions, communion of saints, the strains of authenticity, newspapers, manly loggers, salt pork, or the mundane catechism, recitations, and lectures on civilization by lonesome missionaries, teachers, and federal agents. He became a blue raven painter of liberty.

My brother actually inspired me to become a writer, to create the stories anew that our relatives once told whenever they gathered in the summer for native celebrations, at native wakes, and funerals at the mission. Our relatives were great storiers, and natural leaders with many versions of stories and reservation scenes, and for that reason they were associated with the crane totem, the orators of the early Anishinaabe.

Frances Densmore, the musicologist and curious explorer of native cultures, recorded native songs and stories on the reservation. She was mostly interested in the translation of the songs and oral stories. My interests were in the actual creation of the songs and stories, and the totemic variation of stories, not in the mere concepts and evidence of culture. The specialists forever collected native stories and concocted a show of conceptual traditions. The culture was ours, of course, and the show was never the same in the studies by outside experts. Similar stories were told over and over with many personal and communal variations at native festivals, funerals, and summer celebrations. The heart and humor of native stories and cultures are never in the books of outsiders.

Aloysius inspired me to create visionary stories and scenes of presence, stories that were elusive and not merely descriptive. The scenes of blue ravens in court, ravens balanced on the back of a black horse, and seven blue ravens perched in a caboose were memorable. He created abstract ravens in motion, the very scenes of his visions and memory, but words were too heavy, too burdened by grammar and decorated with documented history to break into blue abstract ravens and fly. My recollections of the words in stories were not the same as artistic or visionary scenes, not at first. Dreams are scenes not words, but one or two precise words could create a vision of the scene. That would be my course of literary art and liberty.

Frances Densmore visited the reservation that summer and indirectly provided me with the intuition and the initial tease of visionary songs and stories. Yes, we were twelve-year-old native amateurs at the time, so the actual memory of my inspiration is much clearer today. Densmore recorded hundreds of native singers on a phonograph, a cumbersome machine that recorded sound directly onto cylinders. We had heard the songs of shamans and animals, of course, but we had never heard the immediate recorded tinny sound of a human voice.

Densmore recorded singers and the song stories, the situation, cultural significance, and descriptive meaning of the song. The stories of the songs inspired me, and by intuition the actual creation of written scenes and stories became much easier for me.

Densmore, for instance, recorded this song by Odjibwe, the traditional native singer, little plover, it is said, has walked by. Only eight words were translated, nothing more. The song scenes were active and memorable because the listeners understood the story. The song story is what inspired me to create the presence of listeners in the story.

The song dancers imitated the natural motions of the plover, elusive motions to distract intruders and predators. The little plover was alone, always vulnerable near the lakeshore. That sense of motion was portrayed in my three written stories that were inspired by the native song of the plover dance. The listeners and readers must appreciate the chance of the plover.

My first three stories were neatly written on newsprint, and my brother painted two blue abstract ravens for the cover of the plover dance scenes. The first stories were gathered by my mother but were lost in a house fire, never folded or signed on the corner. The fire destroyed the early box camera photographs of my brother and me when we sold newspapers at the station, when we worked in the livery stable of the Hotel Leecy, and the only photographs of us as soldiers in the American Expeditionary Forces. Ignatius was the first to leave for the war, and we were pictured arm in arm at the train station.

The first story was about the cocky little plover with the most sensational wounded wing dance, so impressive that the evasive motion of the plover dance was easily perceived and imitated by envious dancers and predators.

My second story was about the plover with an irregular hobble, an intricate dance that feigned a broken foot and a wounded wing. The elusive dance was so decisive that the plover could only reveal the artistry of the dance to escape the envies of a predator.

The third story was about a plover with a variety of trivial vaudeville performances, feigns, guises, blue raven masks, acrobatic, and deceptive plover dances that entertained and completely distracted and deceived the intruders and predators. The most evasive plover dances were the crafty and clumsy practice of tricky entertainment.

My first three written stories were visionary, and the stories demonstrated by specific metaphors of three plover dances the actual and familiar experiences of natives on the reservation. My last story was the dance of the trickster plover of liberty.

Native saints and secrets were blue, the blue of creation and visions of motion, not deprivation, the conceit of sacrifice, or the godly praise of black and tragic death. Blues were the origin of the earth and stories of creative energy. The mountains emerged from the blue sea and became that singular trace of blue creation and the hues of a sunrise.

Blue morning, blue seasons, blue summer, blue thunder, blue winter nights, and the irony of blue blood. Blue snow at night, blue shadows in the spring light, blue spider webs, and wild blue berries were natural totemic connections. Some nations were blue, coat of arms blue, blue flags on the wind. The chances of native stories, memories, conscience, and the sacred were a mighty blue. Blue ravens were the saints forever in abstract motion, and the traces of blue were eternal in native stories. Blue ravens were the new totem of native motion.