Читать книгу A Connecticut Yankee in Lincoln’s Cabinet - Gideon Welles - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

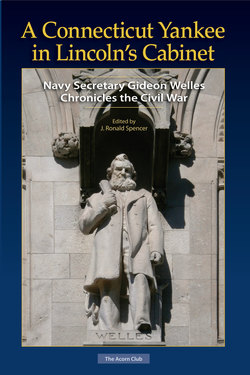

Gideon Welles, a native of Glastonbury, Connecticut, was one of the state’s most influential journalists and politicians during the three decades preceding the Civil War. Today, however, he is usually remembered as Lincoln’s secretary of the navy – “Father Neptune” (or just “Neptune”) as the president called him. He was only the fourth Connecticut resident appointed to a cabinet post, which he continued to hold throughout Andrew Johnson’s presidency.1

Historians usually credit Welles with being an energetic and effective administrator who did much to modernize a service in the grip of an aging uniformed leadership that was rigidly set in its ways. When in July 1861 Congress authorized him (and also the secretary of war) to take into consideration merit as well as seniority in making assignments, Welles proceeded to appoint younger, less tradition-bound officers to key positions. He also oversaw the Navy’s growth from fewer than 100 ships to 671 and the organization and implementation of the increasingly effective blockade of 3500 miles of Confederate coastline. Furthermore, after some initial hesitation, he pushed for the development of ironclad warships, including the famous USS Monitor that fought the ironclad CSS Virginia (formerly the USS Merrimack) to a draw on March 9, 1862, thereby saving the wooden Union warships stationed in Hampton Roads, Virginia, from virtually certain destruction.2 He was, in short, one of the architects of Union victory.

For many historians, however, what is most interesting about Welles is the extensive diary he kept during the war.3 It provides first-hand information, and often perceptive insights, about Lincoln, Welles’s cabinet colleagues, and their conflicts and rivalries. It also covers a wealth of other topics – topics as varied as a cabinet discussion of what the track gauge of the planned transcontinental railroad should be (Welles favored 4 feet, 8½ inches, which became standard for American railroads); home-state pressure on Welles to establish a navy yard in New London; the July 1863 New York City draft riots, which Welles blamed mainly on New York’s Democratic governor, Horatio Seymour, whom he dubbed “Sir Forcible Feeble;” Welles’s fear, as a lifelong hard-money man, that the government’s issuance of paper currency not convertible to gold would lead to financial disaster; and the cabinet’s opposition to a proposed constitutional amendment declaring the United States a Christian nation.

Despite his achievements as navy secretary, Welles was often the target of public criticism. When rebel cruisers wreaked havoc on American maritime commerce, merchants and ship owners blamed him for their losses. Newspapers regularly faulted him because so many blockade-runners managed to evade navy patrols and bring cargo into and out of Confederate ports. Armchair admirals were quick to second-guess his decisions. And cartoonists had a field day at his expense. Welles rarely replied to his critics, but he sometimes vented his anger in the diary. For instance, on December 26, 1863, he wrote

In naval matters … those who are most ignorant complain loudest. The wisest policy receives the severest condemnation. My best measures have been the most harshly criticized…. Unreasonable and captious men will blame me, take what course I may.

The diary also provided an outlet for Welles’s resentment that the War Department failed to give the navy due credit for its contribution to such successful combined army-navy operations as the capture of Vicksburg on the Mississippi River in 1863. He was confident, however, as he wrote on August 23, 1864, that “history will put all right,” although he predicted it would be a generation or more “before the prejudices and perversions of partisans will be dissipated, and the true facts be developed.”

Welles began the diary sometime between July 14 and August 11, 1862 (the first entry is not dated), started keeping it on a regular basis shortly thereafter, and continued to make regular entries in it through the Johnson administration.4 In the entry for October 20, 1863, he noted that work on it “usually consumes a late evening hour, after company has gone and other labors of the day are laid aside.” He rarely went more than a few days without making an entry.

The diary has an immediacy rarely found in memoirs, since it records the rush of events as they happened, when it was uncertain what they signified, how the Lincoln administration should respond, or how they would look in retrospect. As Welles acknowledged in a passage inserted into the September 19, 1862, entry at a later date, “I am not writing a history of the War…. But I record my own impressions and the random speculations, views, and opinions of others also.” Moreover, since he usually wrote about events the day they occurred or soon thereafter, the diary’s pages are largely unaffected by the hindsight that often distorts the recollections of memoirists writing well after the events they discuss.5 The sense of immediacy is further heightened by Welles’s forceful, often impassioned prose.

This book contains some 250 excerpts from the wartime portion of the diary. They are organized into 10 topical chapters, and many of the excerpts are annotated by the editor.6 In an Afterword, Welles’s post-war activities in the Johnson administration and then in retirement are summarized.

Some diary entries appearing here, such as those about the Emancipation Proclamation, the attempt by Senate Republicans to force Lincoln to reorganize his cabinet in December 1862, and the scene at the Petersen house as Lincoln lay dying, have often been cited by historians (though rarely reproduced in full). Many of the lesser-known passages are included for what they reveal about important historical figures and events; others offer interesting sidelights on the war or illuminate Welles’s personal qualities.

Welles recorded numerous comments about Lincoln, whom he liked and respected, but of whom he could also be critical, as is evident in multiple excerpts. Lincoln likewise held Welles in high regard, valued his advice, and apparently enjoyed his company, except on those occasions when he rushed to the White House in high dudgeon over some issue. The Welles-Lincoln relationship was strengthened because Welles’s wife, Mary, was among Mary Todd Lincoln’s few close female friends in Washington. One bond between them was that they both lost a child in 1862. Mary Welles helped nurse the dangerously ill Tad Lincoln when his mother was prostrate with grief over the death of his older brother Willie in February. Nine months later Mary’s youngest child, Hubert, died at age four – the sixth of the Welles children to die in childhood or adolescence. She also rose from a sick bed to attend Mrs. Lincoln following Lincoln’s assassination.7

The diary is studded with Welles’s usually shrewd, often caustic, sometimes unfair characterizations of his cabinet colleagues, senior army and navy officers, and other prominent public figures. Many such passages are found in the ensuing pages.

The book also contains excerpts about numerous other subjects. Among them are a scheme to colonize freed slaves in Central America; the debate over whether Lincoln should authorize the use of privateers against blockade-runners and Confederate commerce raiders; Welles’s disagreements with Secretary of State William Henry Seward – and sometimes with Lincoln – about enforcement of the blockade; the adverse impact of conscription on navy recruitment of able-bodied seamen; various Connecticut-related matters in which Welles perforce became involved; his resistance to attempts to politicize hiring and firing at the navy yards; and his periodic musings about the war’s causes, course, and probable consequences.

Welles was born in 1802 into a relatively prosperous family, the fourth of five sons of Samuel and Anne Hale Welles.8 The family traced its lineage to Thomas Welles, an early settler of Hartford and the fourth man to serve as governor of Connecticut colony. Samuel was successively a farmer, merchant, exporter of agricultural products to the British West Indies, and money lender. He was also active politically. At a time when the Federalist Party dominated Connecticut politics, he enthusiastically supported Thomas Jefferson. Glastonbury voters elected him first selectman and later sent him to the state legislature. He also represented the town at the convention in 1818 that framed Connecticut’s first constitution.9

Gideon Welles was educated at the local district school, the Episcopal Academy in Cheshire, Connecticut, and the American Literary, Scientific, and Military Academy in Norwich, Vermont. As a young man he lacked direction. He twice began the study of law, but each time abandoned it essentially out of boredom. He helped his father with his investment and mortgage business; and a paternal loan enabled him to try his hand at wholesale merchandising. In 1823 and 1824 he published, under a pen name, five vignettes in the New York Mirror and Ladies Literary Gazette. But after this initial success, a series of rejection letters from the Mirror and other publications ended his hopes for a literary career.

In 1825, during his second try at mastering the law, Welles finally discovered the dual vocation to which he would devote most of his adult life: journalism and politics. These occupations were closely linked in the 19th Century, when most newspapers were party organs and editors were well-represented among party leaders at the local, state, and national levels.

Welles began writing for the Hartford Times in 1825 and assumed editorial direction of the paper the following year. He quickly distinguished himself as an outspoken champion of Andrew Jackson’s presidential candidacy. Over the next several years, he concentrated on making the nascent Democratic Party an effective vote-getting organization and the Times its leading editorial voice in the state. Although Jackson lost Connecticut in both 1828 and 1832, the party steadily gained strength, partly because of Welles’s efforts. In 1836, Martin Van Buren, Jackson’s hand-picked successor, carried the state. And in 1835, 1836, and 1837, the Democrats elected the governor and won majorities in the state legislature.10 This enabled them to enact several reforms Welles advocated, including a mechanic’s lien law, the end of imprisonment for debt, and the nation’s first general incorporation law. As an exponent of the egalitarian strain of Jacksonian Democracy, Welles supported the latter measure out of a conviction that if the state intended to continue issuing corporate charters, it should make them generally available, not grant them only to the wealthy, politically well-connected few.

Welles continued to play a major leadership role in the state party well into the 1840s. Although he turned the editorship of the Times over to Alfred E. Burr in 1837, he still wrote many of its editorials. He also crafted many of the party’s annual campaign platforms, influenced the distribution of federal patronage in the state, maintained extensive correspondence with prominent Democrats in other states, and traveled to Washington periodically to talk strategy with other party leaders. From 1836 to early 1841 he was Hartford’s postmaster, a plum patronage appointment. In 1846, President Polk named him to head the Navy Department’s Bureau of Provisions and Clothing, a post he held until June 1849, when President Zachary Taylor replaced him with a fellow Whig.

In the later 1840s, Welles’s influence declined as other ambitious – and in his view unprincipled – men moved to take over the state party. The issue of slavery’s expansion into the western territories deeply divided Connecticut Democrats, as it did Democrats throughout the free states. Welles personally favored the Wilmot Proviso, which, if enacted, would have barred the institution from the vast area the United States acquired from Mexico at the close of the Mexican-American War in 1848. As a patronage appointee in the Polk administration, however, Welles had to be very circumspect about the Proviso, which was anathema to the president.

Welles’s enemies in the state party – foremost among them Isaac Toucey – were eager not to offend their southern Democratic brethren.11 Thus they rejected the Wilmot Proviso in favor of the doctrine of “popular sovereignty,” which left it to the settlers of each territory to decide whether to permit slavery. Welles was sure popular sovereignty would lead to the institution’s spread.

In 1848, some Connecticut Democrats bolted to the new Free-Soil Party, which was committed to confining slavery within its existing geographic boundaries. Although sympathetic to the Free-Soilers, Welles did not join them, lest he jeopardize his job in the Navy Department.12 The bolt further weakened his position within the state Democratic Party, since many of the bolters had been his allies in the struggle for control of it.

Returning home from his three years in Washington, Welles signaled his dissatisfaction with the conservatives now dominating the party in Connecticut by identifying himself as an “independent Democrat” whose politics, he liked to think, were determined by principles and conscience, not party bosses or political expediency. He hoped President Franklin Pierce, the dark horse candidate the Democratic national convention nominated in 1852 after 49 contentious ballots, would move the party in a free-soil direction. But Pierce soon proved to be a “doughface” – a northern man with southern principles who faithfully did the bidding of the party’s slave-state wing.13

Welles’s already tenuous party loyalty was further weakened by the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854. The act repealed the ban on slavery above 36º 30’ of north latitude in the Louisiana Purchase, a ban adopted as part of the Missouri Compromise 34 years earlier. Sponsored by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas and backed by President Pierce at the insistence of southern Democrats, the act was widely seen in the North as betraying a time-hallowed covenant between the free and the slave states. Like countless northerners, Welles attributed its passage to an increasingly aggressive “slave power.”

The act proved to be disastrous for the Democratic Party: in the ensuing Congressional elections the party lost 67 of the 92 northern House seats it had held in the Congress that enacted the measure. Many of these losses came at the hands of insurgent “anti-Nebraska” candidates backed by an ad hoc coalition of outraged Whigs, dissident Democrats, and Free-Soilers, a coalition that prefigured the Republican Party.14 The nativist American Party (discussed below) also contributed to the Democratic debacle in Connecticut and some other states.

By mid 1855, Welles had concluded that the Democratic Party was beyond redemption – a conclusion he arrived at in part because under relentless pressure from conservative Democrats Alfred E. Burr, editor of the Hartford Times, had closed the paper’s pages to him. For a time he was uncertain whether and where he would find a new political home. In early February 1856, however, with a presidential election on the horizon, he was among about a dozen ex-Whigs, Free-Soilers, and independent Democrats who met in Hartford to found the state’s Republican Party. Again he immersed himself in building a new party from the ground up. His first step was to establish the Hartford Evening Press, which would do for the fledgling Republican Party what the Hartford Times had done for the fledgling Democratic Party three decades earlier. He declined the editorship, but wrote many of the paper’s editorials during its start-up phase.

Welles represented Connecticut on the Republican national committee and attended the party’s first presidential nominating convention at Philadelphia in June 1856. Named to the 22-member platform committee, he, together with his Jackson-era friend Francis Preston Blair, Sr., drafted much of the party’s first national platform.

John C. Fremont, the Republican presidential nominee, carried Connecticut in the November election. For the Republican Party to become a lasting force in the state’s politics, however, it would have to meet two challenges. First, the former Whigs, who constituted the party’s largest component, and its much smaller contingent of ex-Democrats, would have to put aside their old partisan animosities in the interest of party unity. This they managed to do despite lingering tensions.

A greater challenge was posed by another new political organization, the American (or Know-Nothing) Party. Running on an anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic platform, it did remarkably well in the 1854 legislative elections and continued to prosper for several years, taking the governorship and three of Connecticut’s four seats in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1855 and winning the gubernatorial contest again in 1856. Many Connecticut Know-Nothings were not only nativists but also opposed to slavery’s extension; and many anti-slavery Republicans also harbored nativist sentiments. Thus some leaders of the two parties favored bringing them together in a formal alliance, or even merging them into a single entity. Detesting ethnic and religious bigotry, Welles opposed any merger. He was enough of a practical politician, however, to support cooperation between Republicans and Know-Nothings, provided that his party avoided taking a nativist stance.

The two parties did cooperate during the 1856 presidential race, when many of the state’s anti-slavery Know-Nothings, like their counterparts elsewhere in the North, were so outraged by the American Party’s tacit endorsement of the Kansas-Nebraska Act that they backed the breakaway North American Party, which endorsed Fremont. The result in Connecticut was a hybrid Electoral College ticket composed of three Republicans and three North Americans. The following year the two parties held a joint convention at which Alexander Holley, whose support came largely from the Know-Nothing delegates, won the gubernatorial nomination by a wafer-thin margin over the candidate preferred by most Republican delegates, William A Buckingham, who was free of any Know-Nothing taint.

Ultimately, the Republican Party won over a large share of Connecticut’s Know-Nothing voters and absorbed many of the American Party’s leaders. To Welles’s satisfaction, it did so largely on its own terms as nativist passions subsided while hostility to slavery’s extension and the “slave power” continued to intensify. The turning point came in 1858, when the party spurned Governor Holley’s bid for a second term, nominated Buckingham instead, and went on to win the gubernatorial race without making significant concessions to the Know-Nothings.15

By 1860, the Know-Nothing movement was defunct; the Democratic Party’s perceived subservience to the “slave power” had seriously weakened it in Connecticut (as it had in much of the North); and relative harmony prevailed between the ex-Whig and ex-Democratic components of the Republican Party, as was exemplified by Welles’s selection to head the state’s delegation to the Republican national convention at Chicago in May.

Welles was optimistic about the party’s chances of taking the White House in 1860. But he strongly opposed the frontrunner for the nomination, William H. Seward, a U.S. senator since 1849 and previously a two-term governor of New York. He not only distrusted Seward as a longtime leader of the Whig Party but also believed he was an unprincipled opportunist who wanted to centralize power in Washington at the expense of the states and was tainted by the corruption characteristic of Empire State politics. In the months preceding the Chicago convention, Welles wrote several forceful anti-Seward articles for influential newspapers in New York City and Washington, helped convince the Connecticut delegation not to cast any of its 12 votes for him, and worked to deny him support in other New England states, which Seward was counting on to back him heavily.16

Welles favored Salmon P. Chase, formerly a U.S. senator and governor of Ohio, for the nomination. But he had also been impressed by Lincoln when the two men talked during the Illinoisan’s visit to Hartford in early March as part of a speaking tour in New England following his heralded Cooper Union address in New York City.17

At the Chicago convention, Seward led on the first ballot, but to Welles’s satisfaction he drew far fewer votes from New England delegates than expected. Thereafter, his candidacy stalled, and on the third ballot Lincoln was nominated, mainly because a majority of the delegates concluded that he had a much better chance than Seward of carrying the key battleground states of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Indiana, and Illinois, all of which the party had lost in 1856.18

Although Welles voted for Chase on all three ballots, he deemed Lincoln a worthy candidate and would give him unqualified support in the general election. He was part of the delegation of Republican leaders that traveled to Springfield after the convention to formally notify Lincoln of his nomination. The nominee greeted him warmly and made reference to their conversation in Hartford the previous March.

Lincoln learned early in the morning of November 7th that he had won the election and within hours began the politically delicate task of forming a cabinet. Determined to maintain sectional and political balance, he intended to give one seat to a prominent New Englander, preferably a former Democrat. Welles was on the short list from the start. But cabinet-making took time and involved the juggling of numerous competing claims. Thus Welles didn’t receive definitive word that Lincoln had chosen him until February 28th, just four days before the inauguration. Even then it was uncertain whether he would become postmaster general or secretary of the navy. That question was answered on March 5th when the president submitted his name to the Senate for confirmation as the latter.

Welles brought to the cabinet a number of political convictions and personal characteristics he had exhibited in the pre-war decades. Like his father, he revered Thomas Jefferson and believed the key to Jefferson’s greatness was his faith in the capacity of ordinary people for self-government. Lincoln and Welles both understood that the fate of democracy was at stake in the Civil War. As Lincoln declared in his July 4, 1861, message to a special session of Congress:

[Secession] presents to the whole family of man, the question, whether a constitutional republic, or a democracy – a government of the people, by the same people – can, or cannot, maintain its territorial integrity, against its domestic foes …. It forces us to ask: “Is there, in all republics, this inherent and fatal weakness?” “Must a government, of necessity, be too strong for the liberties of its own people, or too weak to maintain its own existence?”19

Over the next four years, both men exerted themselves unrelentingly to ensure that those daunting questions were answered in the negative and the country would emerge from its severest trial with democracy intact.

In keeping with his Jeffersonian predilections, Welles had always advocated strict construction of the Constitution and staunchly defended states’ rights, believing it was the states, not the federal government, that could best safeguard the rights and liberty of the individual. Yet unlike many proponents of strict construction and states’ rights, northern as well as southern, his thinking took a decidedly anti-slavery turn. He viewed the Constitution’s fugitive slave clause as exclusively an agreement among the states to return runaways to their owners, not a grant of power to the federal government. Thus he thought the Fugitive Slave Act adopted as part of the Compromise of 1850 was unconstitutional. He also rejected slaveholders’ claims that they had the right to take their human property into the territories, since he found nothing in the Constitution that authorized the federal government to establish or protect slavery anywhere that it had exclusive jurisdiction, which he believed it did in the territories.

As to slavery in the southern states, Welles deemed it a local institution that was created by state law and shielded from federal interference by the Constitution. Under the impact of secession and war, however, he, like Lincoln and many other northerners, concluded that the president, as commander in chief of the armed forces, could emancipate the slaves in the rebellious states on grounds of military necessity, which overrode the constitutional protection slavery enjoyed as long as the people of those states had remained loyal to the Union.

Welles was sincere in espousing states’ rights and always feared that creation of an over-mighty central government would jeopardize individual liberty. Thus he was privately critical of the Lincoln administration’s wartime infringements of civil liberties.20 And as will be seen in the Afterword, his states’ rights convictions caused him fervently to oppose the entire Reconstruction program the Republican-controlled Congress adopted after the war. Yet he was also a nationalist. Like Andrew Jackson, he rejected John C. Calhoun’s theory that each state’s rights included the right to nullify federal laws. And he of course denied that states had a right to secede.

Finally, Welles personified many traits of character and personality associated with the stereotypical Yankee. He was a man of stern moral rectitude who set great store by honor, integrity and propriety. Strong-willed, high-minded, and judgmental, he sometimes fell prey to self-righteousness and was frequently irascible and short on tact. He occasionally lost his temper, but rarely lost his composure during a crisis. Conscientious to a fault, he had an abiding sense of patriotic duty (a word that appears frequently in his diary) and was severely critical of men he thought were putting personal or partisan interests ahead of their country’s welfare. He believed politics should be about principle, not the mere pursuit of power and patronage. He drove himself hard, since his conscience would tolerate nothing less. (On March 31, 1863, he noted in the diary that during a two-week illness he had missed only one day at work.) He had a pessimistic streak and was something of a stoic, which helped him cope with political disappointments and military setbacks – and also with the ordeal of having six of his nine children predecease him. Despite his sometimes unruly wig, in photographs the mature Welles looks very much the dignified, sober-sided, austere Yankee gentleman that he was.

During the Civil War, a number of Connecticut men won distinction for their contribution to the Union cause. For example, William A. Buckingham, the “War Governor” who worked tirelessly to promote enlistments in the army; New Haven-born Admiral Andrew Hull Foote, whose gunboat flotilla played a key role in the campaign against Forts Henry and Donelson in February 1862; and General Alfred H. Terry, who commanded the troops that in combination with the navy took Fort Fisher in January 1865, thus sealing off Wilmington, North Carolina, the last major Confederate port that had remained open to blockade-runners. But it is Welles who stands foremost among them, for both his leadership of the Navy Department and the informative, insightful, often provocative diary he left to posterity.

_______________________

1 The first three were Oliver Wolcott, Jr., secretary of the treasury under Washington and John Adams; John M. Niles, postmaster general during the Van Buren administration; and Isaac Toucey, who was both attorney general in the Polk administration and Buchanan’s secretary of the navy.

2 Of the 671 warships, 559 were powered wholly or in part by steam, and more than 70 were ironclads. James M. McPherson, War on the Waters: The Union and Confederate Navies, 1861 – 1865 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), pp. 35-36, 98-105, and 224. On the initiation of the blockade, see McPherson, Chapter 2, and Craig L. Symonds, Lincoln and His Admirals (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), Chapter 2.

3 This was not Welles’s first turn as a diarist. In earlier life he also had kept a diary periodically. The manuscript of his 1836 diary is on deposit at the Connecticut State Library, and diaries he kept in various years between the 1820s and the mid 1850s are held by the Connecticut Historical Society.

4 Published editions of the diary contain an opening chapter entitled “The Beginning of the War” in which Welles discusses such major events of 1861 and early 1862 as the Fort Sumter crisis, the Confederates’ seizure of the Gosport (Norfolk, Virginia) Navy Yard, the replacement of Secretary of War Simon Cameron by Edwin M. Stanton, and the panic in Washington that the Merrimack would steam up the Potomac and bombard the capital. Welles says nothing, however, about navy Captain Charles Wilkes’s forcible removal of two Confederate envoys, James Mason and John Slidell, from the Trent, a British mail packet, in November 1861, which precipitated a crisis in Anglo-American relations that could have led to war. It did not because the Lincoln administration decided in late December to free the envoys and allow them to go on their way (Mason to England and Slidell to France). The omission is curious given the episode’s intrinsic importance and the navy’s central involvement in it. In any event, this chapter was not a part of the diary per se, having been written no earlier than 1864 and probably not until the 1870s. Since it was not written contemporaneously with the events it recounts, it is used sparingly in this book. When it is cited, it is as “Chapter 1,” followed by the page number.

5 After the war – probably in the 1870s – Welles made numerous revisions to the diary. Some of them did reflect the influence of hindsight. For example, he softened some of his criticisms of the martyred Lincoln and modified some passages to cast a less favorable light on men with whom he had bitter political differences during Reconstruction. Further revisions were made by his son Edgar, who edited the edition published in 1911. How these revisions are treated in this book is explained in the Editorial Note following the Introduction.

6 Most passages are excerpted from diary entries in which Welles discusses multiple subjects. Some entries that deal exclusively with a single topic are reproduced in their entirety.

7 Jean H. Baker, Mary Todd Lincoln: A Biography (New York: W.W. Norton, 1987), pp. 212 and 247; Catherine Clinton, Mrs. Lincoln: A Life (New York: Harper Collins, 2009), p. 248; and Welles’s diary entry for April 14, 1865.

8 Most of the factual material in this overview of Welles’s pre-war life and career is drawn from John Niven, Gideon Welles: Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973; paperback edition, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1994), Chapters 1 – 17. The Afterword also draws on Niven’s book, Chapters 26 – 30, as well as on the postwar portion of Welles’s diary.

9 This topic is treated in Richard J. Buel, Jr., and George J. Willauer, eds., Original Discontents: Commentaries on the Creation of Connecticut’s Constitution of 1818, published by the Acorn Club in 2007.

10 Connecticut held legislative and gubernatorial elections annually, in early April.

11 See Chapter 7 for an account of how Toucey, as Buchanan’s secretary of the navy, advocated appeasing South Carolina during the crisis over Fort Sumter.

12 If Welles had gone over to the Free-Soilers, Polk surely would have sacked him. For financial and other reasons, Welles was eager to retain his position.

13 On the doughfaces, see Leonard L. Richards, The Slave Power: The Free North and Southern Domination, 1780 – 1860 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000).

14 For a perceptive account of the Kansas-Nebraska Act and its consequences, see David Potter, The Impending Crisis: 1848 – 1861, completed and edited by Don E. Fehrenbacher (New York: Harper & Row, 1976), Chapters 7 – 10.

15 On the relationship between Republicans and Know-Nothings in the North, including Connecticut, see William E. Gienapp, The Origins of the Republican Party, 1852-1856 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987) and Tyler Anbinder, Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992).

16 As will be seen in several of the ensuing chapters, Welles’s suspicion and mistrust of Seward persisted during their years as colleagues in Lincoln’s cabinet.

17 Lincoln spoke in five Connecticut cities between March 5th and 10th. In addition to Hartford, they were Norwich (where he met with Governor Buckingham, who was in a very tight race for reelection), Meriden, New Haven, and Bridgeport. See Harold Holzer, Lincoln at Cooper Union: The Speech That Made Abraham Lincoln President (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004), pp. 192-201.

18 A detailed account of the balloting is given in Murat Halstead, Caucuses of 1860: A History of the National Political Conventions of the Current Presidential Campaign (Columbus, Ohio: Follett, Foster, and Co., 1860), pp. 146-149.

19 Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1953), Vol. IV, p. 425.

20 For instance, in his May 23, 1864, diary entry he condemned the government’s temporary seizure of two Democratic newspapers in New York City that had been duped into publishing a phony presidential proclamation.