Читать книгу Shorter Walks in the Dolomites - Gillian Price - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

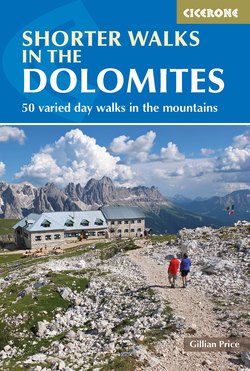

The fantastic approach to the Nuvolau (Walk 21)

The Dolomites

A traveller who has visited all the other mountain-regions of Europe, and remains ignorant of the scenery of the Dolomite Alps, has yet to make acquaintance with Nature in one of her loveliest and most fascinating aspects.

John Ball, Guide to the Eastern Alps (1868)

Like the Alps to which they belong, the astounding Dolomite mountains in northeast Italy were long regarded with awe and a good dose of fear by the populations of herders and woodcutters who clustered round their bases. It was not until the 1800s, and the advent of ‘travelling’, that the first leisure-seeking visitors, Britons for the most part, ventured through treacherous passes to marvel at the spectacular scenery and gape at the brilliant sunsets. Published accounts and guidebooks began to appear, and soon tourists and mountaineers from all over Europe flocked to explore the magnificent heights, which were untrodden until then except by the odd chamois hunter.

Nowadays, the fantastic Dolomites are an exciting and prime holiday destination in both summer and winter. Superbly located resorts are connected by excellent public transport and well-maintained roads, while an ultra-modern system of cable-cars and lifts whisks visitors to dizzy heights in a matter of minutes. It is a memorable alpine playground. Nature lovers will be delighted by the fascinating wildlife to be found in the vast expanses of magnificent forest and high-altitude rockscapes, not to mention the sweet alpine meadows that are transformed in summer into oceans of wild flowers straight out of The Sound of Music. High above are breathtakingly sheer bastions and spires of delicately pale rock in an enthralling succession of bizarre sculpted shapes. This is all easily appreciated thanks to a great network of signed paths and welcoming refuges, where lunch and refreshments can be enjoyed with a beautiful alpine backdrop thrown in for free. By exploring the vast extent of the spectacular Dolomites, this guidebook offers a selection of exciting walks suitable for walkers of all ages, abilities and energy. Routes range from straightforward leisurely strolls to strenuous outings, and each can be completed in a single day.

In addition to natural beauty, the valleys of the Dolomites offer attractions ranging from old-style farms – still run according to ancient traditions – to towns including Trento, Bolzano and Bressanone, which boast priceless medieval and Renaissance art treasures and make for a fascinating visit on any rainy days. Early peoples fleeing barbaric invaders in about the fifth century, many of whom spoke the ancient Rhaeto-Romanic language known as Ladin, made their homes in the protection of the remote mountain valleys. Incredibly, Ladin has survived to this day and is now the declared mother tongue of 4.3% of the inhabitants of the South Tyrol (Alto Adige in Italian), which accounts for a third of the Dolomites. However, the region is dominated by the German language (68.2% of the population), which is the legacy of sixth-century invaders and later Austro-Hungarian domination. Along with the adjoining Italian-speaking Trentino, it has been part of Italy since 1919. That was ratified in the wake of the First World War, which had seen the Dolomites transformed into a terrible war zone where the crumbling Hapsburg Empire fought the fledgling Italian Republic on mountain passes, crests and even glaciers. Many of the old military mule tracks are still walkable and many wartime trenches and fortifications are often encountered on the walks in this guidebook, all poignant reminders of man’s folly. The remaining southeastern chunk of the Dolomites is administered by the Veneto region, which is based in Venice. Centuries before, during the glorious era of the Serenissima Republic, which stretched from the sixth century until the late 1700s, immense rafts of timber were piloted downstream to the city for its foundations and ships.

Fossilised dinosaur footprints on the Pelmo (Walk 18)

Valleys and Bases

While the Dolomites are quite compact, their geography and countless valleys can make exploration pleasantly time-consuming. The overview that follows aims to help visitors understand the layout, find their way around and choose a handy base for walks.

Val Sassovecchio with Cima Uno (Walk 8)

Beginning on the northernmost edge of the Dolomites, in the primarily German-speaking South Tyrol, is broad Val Pusteria. Running east–west, it acts as a low-key thoroughfare for rail and road traffic between Italy’s main Isarco-Adige valley and Austria. Towards the eastern end, Valle di Braies branches off to enchanting Lago di Braies. Served by a summer bus, there is a glorious historic hotel, a café-restaurant and a plethora of memorable picnic spots. Walks 1 and 2 start out here.

Val d’Arcia and the Pelmo from Passo Staulanza (Walk 18)

A southern branch climbs to the marvellous uplands of Pratopiazza, where a hotel and refuges offer accommodation and meals. It is served by a summer bus and is perfect for Walk 3.

In the east lie the spectacular Sesto Dolomites. The well-served picturesque towns of San Candido (trains and buses) and Sesto (buses) make good bases for forays into this group, and they have a good range of accommodation and shops. Walks 6 and 8 begin their exploration here, while Walk 7 starts out from Passo Monte Croce Comelico, a road pass (easily reached by bus) on the easternmost edge of the Sesto group, with a hotel and café.

The southern realms of the Sesto group can be accessed from Misurina, a handy small-scale resort with summer bus services, a scattering of guesthouses and cafés, a grocery store and a camp site. It stands on the shores of an attractive much-photographed lake, and has plenty to keep walkers busy for a couple of days as Walks 9, 10, 11 and 12 begin close by. To the southwest, a short bus ride or drive away is Passo Tre Croci and the start of Walk 13 to the Sorapiss.

Branching north from Misurina, you come to the Val di Landro at Carbonin. A short distance on is a small lake at Landro, with its café, bus stop and hotel, where Walk 5 begins. Reversing direction and heading southwest via the watershed at Cimabanche, the Walk 4 turn-off is reached. It is also accessible from Fiames, which is towards Cortina.

In the Italian-speaking Veneto region and located at a strategic intersection of roads leading in from the Dolomite passes, the attractive and renowned jet-set resort town of Cortina d’Ampezzo is an excellent base for walkers for a couple of nights, although it can get rather busy (not to mention pricey). It has shops galore, hotels and year-round long-distance bus links as well as local summertime runs to strategic Passo Falzarego and nearby Passo di Valparola, where there are also guesthouses and cafés. Accessible from Cortina are Walks 13 and 19–26, the latter group leading to the famous Cinque Torri, Nuvolau, Tofane, Lagazuoi and neighbours.

At Forcella Col Negro the Civetta’s western wall comes into view (Walk 17)

The scenic Val del Boite leads southeast to Pieve di Cadore, the birthplace of Renaissance artist Titian. A handy place for exploring the Cadore district, it has grocery shops, hotels and year-round bus services. Nearby, at the foot of the Marmarole, is the railhead of Calalzo (the start of Walk 14), while slightly further northeast is Domegge (Walk 15).

From Pieve di Cadore, the Piave river valley heads south to Longarone, site of the 1963 Vajont dam tragedy – when entire villages were wiped out by a massive flooding caused by a landslide. The Val di Zoldo branches northwest here, climbing past a string of quiet, hospitable villages in the shadow of the magnificent Pelmo and the Civetta. Forno di Zoldo (hotels, groceries, bus) is the gateway for Walk 16 while Passo Staulanza (guesthouse, summer bus) at the valley head is the start of Walk 18.

Running almost parallel to Val di Zoldo is the Cordevole river valley, which links the outskirts of Belluno to downbeat Alleghe (via Cencenighe) at the foot of the majestic Civetta. This small lakeside village offers buses, shops and accommodation as well as the cable car and lifts used in Walk 17. Further along, at Caprile, is a fork west for the modest resort of Malga Ciapela (bus, hotel, shops), where Walk 43 sets off by cable car to the dizzy heights of the glaciated Marmolada, the loftiest mountain in the Dolomites; Walk 44 passes along its south face.

Lying due south is the sprawling, spectacular Pale di San Martino group, which is easily reached from the railhead of Feltre thanks to year-round buses. (A tad above Feltre itself is Passo Croce d’Aune, where there is a hotel and summer bus, and the start of strenuous Walk 48.) Useful nearby towns are Fiera di Primiero (accommodation, shops), for Walk 47, and San Martino di Castrozza (hotels, shops and lifts), for Walk 46. Higher up is Passo Rolle (accommodation and cafés), for Walk 45.

The curious Campanile di Popena (Walk 12)

The path round Lago di Carezza (Walk 38)

To the north of the Marmolada, the Livinallongo valley leads to the village of Arabba, where a road zigzags west to Passo Pordoi for hotels, bus and cafés. Popular Walk 41 starts off here and Walk 40 ventures onto the superb, if desolate, Sella massif.

From Arabba the road winds north through Passo di Campolungo to the start of important Val Badia, the heart of the Ladin-language district. It is justifiably popular and rather busy at times. Corvara, Pedraces and San Cassiano are well-served, handy bases with a huge choice of accommodation, good bus links and plenty of shops. Walk 27 starts at Pedraces. The valley’s eastern branch climbs to Passo di Valparola (summer bus, guesthouse) and Passo Falzarego, where Walks 20–26 can also be accessed.

At San Martino, towards the northern extremity of Val Badia, is the steep road west for Passo delle Erbe (hotel, café, summer bus) and Walk 28 around belvedere Sass de Putia, the northernmost Dolomite. The road continues down to marvellous Val di Funes and off-the-beaten track Santa Maddalena (bus, accommodation, shops). Nearby, Walk 29 wanders along the edge of the beautiful Odle Dolomites.

Further south, and accessible from Bolzano in the busy Val d’Isarco, is renowned Val Gardena, dotted with bustling resort villages. Lovely Ortisei, Santa Cristina and (smaller) Selva are perfect places for a base as they offer accommodation, shops and year-round buses, and are handy for Walks 30 and 31. Higher up, at Passo Sella (summer bus, accommodation), is the start of Walk 39 around the Sassopiatto-Sassolungo.

Linked with Val Gardena, and also easy to get to from Bolzano, is the extensive Alpe di Siusi upland, dominated by the Sciliar. A good base for Walks 32 and 34 is either the lower village of Siusi or the upper resort of Compaccio. At the mountain foot is the photogenic village of Fiè (year-round bus, hotels, cafés, shops), the start for Walk 33, which wanders over meadows to a castle.

A short distance south, rural Val di Tires branches off Val d’Isarco and climbs towards the flanks of the magnificent Catinaccio; Walk 35 begins at quiet San Cipriano (year-round buses). The road proceeds on to Passo Costalunga (hotel, summer bus), a suitable base for Walk 37 (you can also get here by road and bus from Bolzano via Val d’Ega and Nova Levante). Slightly lower down, at pretty Lago di Carezza, is Walk 38.

From the pass the road continues down to Val di Fassa and Vigo di Fassa (year-round buses, hotels, shops) with its cable car and access for Walk 36. Close-by is Pozza di Fassa and lift access for Walk 42. Popular Val di Fassa has year-round bus runs from the city of Trento and the main railway, and plenty of accommodation and visitor services.

Down in the Val d’Adige, at Trento, year-round buses head west to the intersection at Ponte Arche and access for Walk 50 up dramatic Val d’Ambiez and the southern flanks of the spectacular Brenta Dolomites. The road continues via Tione before veering north along Val Rendena to the renowned resort of Madonna di Campiglio. Along with buses, plenty of accommodation and shops, there is a gondola lift here for Walk 49.

Geology

The magnificent Tre Cime from Rifugio Auronzo (Walk 9)

The rocks of the Dolomites were formed some 230 million years ago, when a shallow tropical sea covered the area and deposits of coral and sea creatures gradually built up on the sea floor. It was not until 65 million years ago that the area underwent the dramatic tectonic events that led to the creation of the alpine chain, when rock slabs began to be upended and lifted hither and thither. A succession of ice ages followed, and erosion from snow, rain and wind continues to shape the wonderful mountains visitors see today.

However, the ‘Pale Mounts’ – as they were first known – attracted curious geologists well before travellers. In 1789 French mineralogist Déodat de Dolomieu identified their composition as the limestone variant calcium magnesium carbonate, which was later named dolomite in his honour. As regards its origin, scholars have long puzzled over the abundance of fossilised shells and marine creatures embedded in the rock at such heights and so far from the sea.

In 1860, with the theory of the biblical Flood long since rejected, German scholar Baron Ferdinand von Richthofen proposed their genesis as a coral reef, work that was further developed by Edmund von Mojsisovics. While the sedimentary nature of dolomite is undeniable, disagreement continues over the nature of its ‘mutation’ from limestone. The earliest theory came from Leopold von Buch in the 1820s. He suggested that the magnesium-rich vapours released from molten volcanic rocks penetrated the limestone, transforming it. More recently, researchers in Brazil have suggested the efforts of industrious bacteria in tropical environs. According to legend, however, the splendidly pale Dolomite rock is a result of it being coated with fine white gossamer woven from moon rays.

Plants and flowers

The Dolomites area boasts over 1500 species of glorious flowering plants. This is a quarter of the total found in the whole of Italy and these blooms alone are a good reason to go walking in summer. Heading the list is the mythical edelweiss. Found in alpine meadows, its felt-like petals form delicate overlapping stars. While not especially eye-catching, its blanched aspect inspired the legend that it was brought down from the moon by a princess, to provide a memory of the pale lunar landscape for which she was pining away.

Unmissable, fat and intensely deep blue trumpet gentians burst through the grass, and there are also daintier star-shaped varieties. Pasture areas also feature orange lilies and the wine-red martagon variety, which vie with each other for brilliance. Stony grass terrain is often colonised by alpenrose bushes, rather like azaleas, with masses of pretty red-pink flowers in late July.

One of the earliest blooms to appear is the alpine snowbell, which has fragile fringed lilac bells that make it visible in snow patches, and it is never far away from hairy pasque flowers in white or yellow. Clearings are the best places to look for the unusual lady’s slipper orchid, recognisable by its maroon petals round a swollen yellow-lipped receptacle, while masses of purple orchids are common in meadows. Gay Rhaetian poppies punctuate dazzling white scree slopes with their patches of bright yellow, never far from clumps of pink thrift or round-leaved pennycress, which is honey-scented. A less commonly encountered flower is the king-of-the-Alps, a striking cushion of bright blue blooms reminiscent of a dwarf version of forget-me-not. A rare treat is the devil’s claw from the Rampion family, which has a pinkish lilac flower with curly pointed stigma that specialises in vertical rock faces. Another rock coloniser is saxifrage, the name literally ‘rock breaker’. Pretty pink cinquefoil also blooms on stone surfaces, its delicate flowers scattered amid starry clusters of silvery-grey leaves.

A couple of flowering plant species are endemic to the Dolomites. Moretti’s bellflower (Campanula morettiana), with its rounded deep blue petals, nestles in rock crevices between 1500 and 2300m, while the succulent Dolomitic houseleek (Sempervivum dolomiticum) prefers sunny dry slopes and sports a bright green stalk and deep pink pointy flowers.

Precious aids to identification are Alpine Flowers by Gillian Price (Cicerone, 2014) and Alpine Flowers of Britain and Europe by C Grey-Wilson and M Blamey, alas long out of print.

Clockwise from top left: Unusual bear’s ear; devil’s claw; round-leaved pennycress

In terms of trees, beech grow up to about the 1000m line before conifers take over. Silver fir, spruce and several types of pine tree mingle with the Arolla pine, which can reach 2600m in altitude and is recognisable for its tufted needles and reddish bark. A further tree of note is the springy low-lying dwarf mountain pine, a great coloniser of scree, while another high achiever is the larch, the sole non-evergreen conifer. It loses its needles with the onset of winter in a copper-tinged rain and can reach up to 2500m. It has legendary origins, created by the forest animals and dwarves as a wedding gift for their generous benefactor and queen. The fronds and bunches of wild flowers they made it from quickly withered, but the queen cast her filmy veil over it – reproduced each spring as the fresh green lacy shoots.

Wildlife

One of the beauties of walking is the chance it gives you to observe the surprisingly abundant wildlife that inhabits these mountains. The easiest sightings are of marmots: adorable furry social creatures a bit like beavers, which live in extensive underground colonies and hibernate from October to April. In the summer months they forage for favourite flowers on grassy slopes, only returning to the safety of their burrows on the shrill warning cry of their omnipresent sentry, an older figure standing stiff and erect on a prominent rock.

The widespread conifer woods provide shelter for roe deer, although often you only catch a fleeting glimpse of them due to their shyness. Higher up, seemingly impossible rock faces and scree slopes are the ideal terrain for herds of fleet-footed chamois: mountain goats with short curved horns like crochet hooks. Another impressive and even more rare creature is the majestic ibex, sporting its distinctive sturdy grooved horns. Due to overzealous hunters, they became extinct here back in the 1700s. However, healthy groups survived in both a royal game reserve in Italy’s Valle d’Aosta and the Engadine in Switzerland. Specimens were brought back to Dolomite habitats around 50 years ago, and there are now well-established groups.

A more recent example of reintroduction is that of brown bears, which had also previously been victim of hunting. However, the dwindling nucleus in the Adamello-Brenta park has been slowly and successfully boosted by bears from Slovenia and the latest head count is 24.

Alpine marmot

Birdwatchers will enjoy the delightful small songbirds in the conifer woods, while sizeable birds of prey such as kites, buzzards and golden eagles may be spotted above the tree line. One special feathered treat is the showy high-altitude wall creeper. Fluttering over extraordinarily sheer rock faces in its hunt for insects, it flashes its plumage (black with red panels and white dots) and attracts attention with its shrill piping whistle. There is also the ptarmigan, a type of high-mountain grouse that nests on grassy slopes and makes sounds a bit like a pig snorting. In winter, with a perfect white plumage camouflage, it can patter over snow surfaces without sinking thanks to fine hairs on its claws, akin to snowshoes. However, the queen of local birdlife is undoubtedly the spectacular capercaillie, a cumbersome dark-coloured ground bird (similar to black grouse) that inhabits conifer woods. A rare sight for the lucky few, your best bet to see one is in autumn, when they scout for laden bilberry shrubs. An excellent guidebook is Birds of Britain and Europe by Bertel Bruun (Hamlyn: London, 1992).

Warning There are two potential dangers in terms of wildlife. The first is bites from ticks (zecche in Italian), which may carry Lyme’s disease (borreliosis) and even TBE (tick-borne encephalitis), which can be life-threatening to humans. The problem is limited to the Feltre-Belluno districts and applies to heavily wooded areas with thick undergrowth. Sensible precautions include wearing long light-coloured trousers (which will show up the tiny black pinpoint insects more easily) and not sitting in long grass. Inspect your body and clothes carefully after a walk for any suspect black spots or undue itching, which is a sign that a tick may have attached itself to you. However, before attempting tick removal by grasping the head with tweezers, take the time (5 minutes) to cut off its air supply by applying a cream, such as toothpaste, or oil, which will oblige it to loosen its grip. If in any doubt, don’t hesitate to go to the nearest hospital, where a blood test for antibodies may be suggested after three to four weeks have passed. More information is available at www.lymeneteurope.org.

The second warning concerns vipers (or adders): smallish light grey snakes with a diamond-patterned back. Their bite can be fatal, particularly for children and the elderly, but it is extremely rare. Although widespread, especially in abandoned pasture and old huts, they are timid creatures that slither away very quickly if they consider themselves to be in danger. Snakes only attack if threatened, so if you meet one – on a path for example, where it is probably sunning itself and may be lethargic – give it ample time and room to move away. In the unlikely circumstance that someone is bitten, seek help immediately, keep the person calm and bandage the affected area.

The landmark church at San Cipriano (Walk 35)

Protected areas

Set up in 1993, the vast Parco Nazionale Dolomiti Bellunesi (www.dolomitipark.it) spreads across rugged ranges in the southernmost Dolomites. Around the same time, as local administrations became more environmentally enlightened, the Dolomiti d’Ampezzo park (www.dolomitiparco.com) appeared in the Cortina district. Both are now making up for lost time with excellent education programmes, forest and wildlife management and path upkeep. Earlier, a host of parchi naturali had been established under the regional jurisdiction of the financially autonomous Trentino-Alto Adige region. The first – the Sesto Dolomites, Fanes-Sennes-Braies, Puez-Odle and Sciliar (see www.provincia.bz.it/natura and click on Parchi naturali) – were followed by Paneveggio-Pale di San Martino www.parcopan.org and Adamello-Brenta www.pnab.it.

The website www.parks.it is useful as it gives a general picture of Italy’s various regional and national parks.

Getting there

The vast outlook from Rifugio Auronzo (Walk 9)

The Dolomite mountains are in the northeastern part of Italy, near the Austrian border. They occupy an area in the shape of a parallelogram that extends across the regions of Trentino-Alto Adige (South Tyrol) and the Veneto. The main block is bordered by the Val Pusteria in the north, Santo Stefano di Cadore and the Piave river valley in the east, a line connecting Belluno, Feltre and Trento in the south and the busy Adige–Isarco river valley running up through Bolzano and Bressanone (as well as the Brenta group near Madonna di Campiglio) in the west.

By plane

The nearest international airports in Italy are at Verona www.aeroportoverona.it, Treviso www.trevisoairport.it and Venice www.veniceairport.it, and in neighbouring Austria at Innsbruck www.flughafen-innsbruck.at. All have good bus services for rail or other coach connections for onward travel.

By train

International lines serve the stations south of the Brenner Pass, as well as Verona to Venice. Eurail passes make train travel an attractive option for under-26-year-olds.

Useful branch lines via Belluno and Vittorio Veneto reach Calalzo, while for the Val Pusteria change at Fortezza, north of Bressanone. See www.trenitalia.com for information and online booking.

By car

Via Europe’s extensive motorway system, the best entry to Italy is by the Brenner Pass from Austria on the A22 autostrada. This leads directly to the northwestern Dolomites, with handy exits from Bressanone southwards. Otherwise, leave the A4 Torino–Trieste via a link near Verona for the A22 northwards. From Mestre, outside Venice, the quiet A27 runs up via Vittorio Veneto, with good roads continuing for Belluno and towards Cortina for the eastern Dolomites.

Well-maintained national roads, labelled SS for Strada statale or SP for Strada provinciale, run through the Dolomites and are referred to in this guidebook, where relevant, in the information box access section at the start of the walks.

By bus

Long-distance coaches from northern Italian cities provide convenient links with the Dolomites throughout the summer season:

ATVO (Venice to Cortina) Tel 0421 594580 www.atvo.it

Autostradale (Milan to Cortina, Val di Fassa and Madonna di Campiglio) Tel 02 33910794 www.autostradale.it

Brusutti (Venice to Caprile, San Martino di Castrozza and Canazei) Tel 041 5416663 www.brusutti.com

Cortina Express (Bologna, Mestre and Venice Marco Polo Airport to Cortina, Val Badia and Val Pusteria) Tel 0436 867350 www.cortinaexpress.it

STAT-Turismo (Genoa–Trentino) Tel 0142 781660 www.statturismo.com

Local transport

The extensive network of trains and buses across the Dolomites is refreshingly inexpensive, easy to use and unfailingly reliable. All but two of the 50 walks in this guidebook start and finish at a point accessible by local public transport and the whole book was researched in this way. What’s more, the bus drivers know the mountain roads and conditions like the back of their hand, leaving passengers free to sit back and enjoy the views. Visitors to the Dolomites are invited to leave their car at home, thereby not contributing to air pollution and traffic congestion in these magical mountains. Many holiday resorts offer free or cut-price bus passes for their guests to encourage this habit. Strategically placed cable-cars and chair lifts are also used on the walks described.

The chair lift and the wonderful views across to the Lagazuoi (Walk 20)

Generally speaking, summer timetables correspond to the Italian school holidays, which usually fall from mid-June to mid-September. Exact dates vary year to year, company to company and region to region, but they can be checked on the relevant websites below.

The main bus companies that operate in the Dolomites are:

Dolomiti Bus (covers the Veneto) Tel 0437 941167 www.dolomitibus.it

SAD (South Tyrol/Alto Adige) Tel 840 000471 www.sii.bz.it

SAF (Friuli-Veneto) Tel 800 915303 www.saf.ud.it

Trentino Trasporti, previously known as Atesina (Trentino including the Trento–Malé train FTM) Tel 0461 821000 www.ttesercizio.it

Cortina Express (Cortina district) Tel 0436 867350 www.cortinaexpress.it

Note Tickets are sold on board for Trentino Trasporti and SAD services. Multi-trip passes starting at €5 (available from SAD) are economical and can be used by more than one passenger. Dolomiti Bus tickets should be purchased beforehand at cafés and shops carrying the logo and stamped on the bus, otherwise a surcharge is levied.

For information on Trenitalia, the Italian state rail company, Tel 892021 or go to www.trenitalia.com. Note Unless you have a booked seat (in which case your ticket will show a date and time) validate (stamp) your ticket in one of the machines on the platform before boarding your train. Failure to do so can result in a fine.

Information

The Italian Tourist Board (www.enit.it) has offices all over the world and can help anyone planning to visit Italy with general information.

Tourist offices in the Dolomites valleys follow; these can provide full details of local accommodation options and transport.

Alleghe Tel 0437 523333

Arabba Tel 0436 79130

Belluno Tel 334 2813222

Calalzo Tel 0435 32348

Cortina d’Ampezzo Tel 0436 3231

Falcade Tel 0437 599241

Feltre Tel 0439 2540

Forno di Zoldo Tel 0437 787349

Misurina Tel 0435 39016

Pieve di Cadore Tel 0435 31644

Rocca Pietore Tel 0437 721319 www.infodolomiti.it

Braies Tel 0474 748660

Dobbiaco Tel 0474 972132

San Candido Tel 0474 913149

Sesto Tel 0474 710310

Villabassa Tel 0474 745136 www.hochpustertal.info

Fiera di Primiero Tel 0439 62407

San Martino di Castrozza Tel 0439 768867 www.sanmartino.com

Colfosco Tel 0471 836145

Corvara Tel 0471 836176

Pedraces Tel 0471 839695

La Villa Tel 0471 847037

San Cassiano Tel 0471 849422 www.altabadia.org

San Martino in Badia Tel 0474 523175 www.sanmartin.it

Alba di Canazei Tel 0462 609550

Canazei Tel 0462 609600

Pozza di Fassa Tel 0462 609670

Vigo di Fassa Tel 0462 609700 www.fassa.com

Alpe di Siusi Tel 0471 727904

Fiè Tel 0471 725047 www.seiseralm.it

Ortisei Tel 0471 777600

Santa Cristina Tel 0471 777800

Selva Tel 0471 777900 www.valgardena.it

Funes Tel 0472 840180 www.villnoess.com

Madonna di Campiglio Tel 0465 447501 www.campigliodolomiti.it

Nova Levante Tel 0471 613126 www.welschnofen.com

Tires Tel 0471 642127 www.tiers.it

When to go

The Dolomites! It was full fifteen years since I had first seen sketches of them by a great artist not long since passed away, and their strange outlines and still stranger colouring had haunted me ever since. I thought of them as every summer came round; I regretted them every autumn; I cherished dim hopes about them every spring.

Amelia Edwards (1873)

Visit the Dolomites between June and October for walking, unless you’re equipped with snowshoes or skis for the marvellous snow season that extends from Christmas to Easter. From early summer many low-altitude walks are feasible and the paths quiet, but it’s worth waiting until July for high-altitude routes to be free of late-lying snow, otherwise accumulations in gullies can conceal waymarking or turn into treacherous ice. Several other factors affect walking: the rifugi (refuge huts) open from late June through to late September, should you rely on them for overnight accommodation or meals, while bus services run from about late June to September (see Local transport). August is the busiest month, with the peak Italian holiday period focusing on August 15th, a national holiday. It is advisable to book accommodation in advance for this time.

July is the best month for flowers, while September to October have cooler conditions and superb visibility as autumn and its crispness approaches, with the chance of the odd snowfall. Late-season walkers will be rewarded with improved chances of observing wildlife in solitude. Italy stays on summer time until the end of October, when there is daylight until about 6pm.

Accommodation

All the Dolomite valleys and villages offer a vast choice of hotel (albergo), guesthouse (locanda), bed & breakfast (affittacamera, Garnì) and even farm stay (agriturismo) options for all pockets. Families with small children will appreciate the freedom of a house (casa) or flat (appartamento); rentals are common, usually on a weekly basis. Suggestions for medium-range hotels are given in Appendix B, otherwise consult the tourist office websites above for full accommodation listings and availability. Reservation in key resorts such as Cortina is not usually necessary outside the August to September peak season, but it is always best to book in advance to save disappointment. Look for signs with zimmer frei or camera libera (room free) if you’re driving through.

Although each walk described in this guide can be completed in a single day, to allow you enough time to return to comfortable valley accommodation, an overnight stay in an alpine refuge is always a memorable experience and can be the highlight of a walking holiday. Contact details are given at the end of the relevant route descriptions. With the odd exception at road level, these marvellous establishments are set in spectacular high-altitude positions accessible only to walkers or climbers. They are open all through the summer months and offer reasonably priced meals and sleeping facilities that range from spartan dormitories with bunk beds to cosy, if simple, guest rooms. Charges are around €18 for a bed and €40 for half board, which means bed, a three-course dinner and breakfast. Most huts are run by the Italian Alpine Club CAI (Club Alpino Italiano) as well as its Trentino branch SAT (Società degli Alpinisti Tridentini), and the South Tyrol club AVS (German Alpenverein Südtirol), as denoted with their listing. All mountain huts, run by the clubs or privately managed, are open to everyone. Members of affiliated alpine associations from other countries receive good discounted rates (50% off bed rates) in line with reciprocal agreements. Brits can join the UK branch of the Austrian Alpine Club (Tel 01929 556870; www.aacuk.org.uk). Members of the British Mountaineering Council and Mountaineering Council of Scotland can buy a Reciprocal Rights Card from the BMC website, www.thebmc.co.uk.

Cheery Rifugio Padova (Walk 15)

Walkers heading for Rifugio Vaiolet (Walk 36)

Pillows and blankets are always provided, so sleeping bags are not needed. Sleeping sheets, however, are compulsory in the club-run huts, so carry your own. Some huts have them on sale. You’ll also need a small towel, not that showers (either hot or cold) are common. A pair of lightweight running shoes or slippers is a good idea, as boots must not be worn inside huts, although guests are sometimes provided with rubber flip-flops or clogs. Hut rules include no smoking and lights out from 10pm to 6am, when the generator is switched off.

Rifugio accommodation should be booked in advance for July and August, especially on weekends for the hot spots. When you phone, tell the guardian: ‘Vorrei prenotare un posto letto/due posti letto’ (I’d like to book one/two beds). Be aware that a booking can set costly (for you!) emergency search procedures in motion if you don’t turn up, so remember to cancel if you change your plans. The occasional ultra-modern rifugio accepts credit cards, but it’s best to carry a sufficient supply of euros in cash, to be on the safe side. All the towns and large villages have an ATM.

The magnificent Vallon delle Lede is flanked on either side by soaring rock towers (Walk 47)

Camping should be restricted to official valley sites, which are always well equipped and often in superb locations. However, a discreet pitch well off a path and away from the huts should not be a problem (unless you are in a park area, where it is strictly forbidden).

Food and drink

While this may not be the gastronomical heart of Italy, foodies will not be disappointed. The German-speaking valleys pride themselves on delicious cereal breads, such as the crunchy rounds of unleavened rye bread with cumin seeds, Völser Schüttelbrot, or a softer yeasty version. Both are a perfect taste match for thinly sliced Speck, a local smoked ham flavoured with juniper berries, coriander and garlic.

Rifugio Viel del Pan is popular with walkers (Walk 41)

In a restaurant, Knödelsuppe or canederli in brodo means traditional farm-style dumplings the size of tennis balls (made of bread blended with eggs), flavoured with Speck and served in consommé. With any luck, the pasta course will include Schlutzkrapfen, home-made ravioli filled with spinach. For a main course in the southern valleys, Tosella – a fresh cheese (vaguely resembling mozzarella) lightly fried in butter or oven-baked with cream – is definitely worth tasting. Otherwise, go for Polenta con formaggio fuso, corn meal smothered with melted cheese, hopefully accompanied by funghi, wild mushrooms. Meat eaters can order spicy goulash or variations of Bauernschmaus, smoked pork and sausages on a bed of warm Sauerkraut, stewed cabbage.

For those with a sweet tooth, the dessert front is dominated by Kaiserschmarm, a scrumptious concoction of sliced pancake with dried fruit and redcurrant jelly. Another special treat (and a meal in itself) is Strauben, fried squirts of sweetened batter with bilberry sauce. Ask at the bakeries for Apfelstrudel or Mohnstrudel, a luscious pastry roll stuffed with apple or poppy seeds respectively.

Some memorable wines hail from the Dolomites. Among the reds are the full-bodied Teroldego and lighter Schiava from the Trentino, as well as excellent Lagrein and Blauburgunder (Pinot nero) from the slopes round Bolzano. The list of whites is headed by the heavenly, aromatic Gewürztraminer, which reputedly originated at Termeno (near Bolzano), while very drinkable Riesling and similar others are produced from grapes grown on the steep terraces over the Isarco valley.

The non-alcoholic Holundersaft, elderberry blossom syrup, is refreshing on a hot summer’s day. Coffee is strictly Italian-style and comes as short black espresso, milky and frothy cappuccino or less concentrated caffe latte, as well as an infinite range of intermediate combinations. Tea is usually served black with lemon. A warming drink on a cold day is thick, rich cioccolata calda, Italian-style hot chocolate.

A short note on drinking water: in towns and villages Italian tap water (acqua da rubinetto) is always safe for drinking and, by law, it is meticulously tested on a frequent basis. You can also request it in any restaurant and café instead of the bottled mineral water that is so widely consumed. Huge amounts of polluting fuel are burnt up every year transporting these bottles to and fro across Europe, but thankfully there is a growing movement of people aware of this incongruity who choose to drink tap water.

What to take

Essentials start with good quality waterproof boots incorporating ankle support and non-slip soles (preferably not brand new, unless you plan to protect your feet with sticking plaster). Trainers are definitely inadequate for alpine paths. You also need a comfortable rucksack, big enough to contain food and drink for a day, along with rain gear and emergency items including a first aid kit. A sun hat, sunglasses and very high factor protective sun cream are essential – remember that for every 1000m of ascent, the intensity of the sun’s UV rays increases by 10%. A range of clothing is needed to cater for conditions ranging from fiery sun through to lashing rain and storms and, occasionally, snow. Lightweight telescopic trekking poles are a handy option to help you descend steep slopes and ease the weight of a rucksack off your knees and back.

Signpost for Rifugio Tre Scarperi (Walk 6)

Always carry a full day’s supply of water as your chances of finding any en route are low and livestock at pasture pollute the rare watercourses. At some huts the water may be labelled non potabile (undrinkable) if supplies come from snowmelt, making it unsuitable due to low salt content. If in doubt, check with the staff, as it may be a simple matter of health service bureaucracy and nothing harmful.

Although food is available at huts on the majority of walks described in this guidebook, it is always best never to rely on them, but always to be self-sufficient and carry generous supplies of your own. Bad weather, minor accidents and all manner of unforeseen factors could hold you up on the track, and that extra biscuit or energy bar could become crucial.

Mineral salt tablets are helpful in combating salt depletion and dehydration caused by profuse sweating; unexplained prolonged fatigue and symptoms similar to heat stroke indicate a problem.

Passo di Costalunga (Walk 37)

Maps

An excellent network of paths penetrates the Dolomites, each marked with frequently placed red and white paint stripes on prominent fence posts, tree trunks and rocks, each complete with their own distinguishing numbers. These numbers and routes are marked on commercial walking maps. While sketch maps are provided in this guide, limitations of space make it impossible to include full details, which are essential in an emergency, so it is imperative that walkers obtain the recommended commercial maps listed in individual walk information boxes. These are Tabacco carta topografica per escursionisti maps at 1:25,000 scale, by far the clearest on the market at present. They use a continuous red line for a wide track and a broken red line to indicate a marked path of average difficulty. Red dots denote routes that are exposed or unclear, while crosses denote aided sections such as cable or ladders and via ferrata routes. The only drawback of the Tabacco maps is the ill-advised substitution of well-used place names with ancient and dialectal versions. While of great historical interest, few correspond to local usage or signposts. The maps can be ordered at www.tabaccoeditrice.com. Smartphone users can download the App for digital maps from www.tabaccomapp.it. The maps are sold throughout the Dolomites and leading overseas booksellers include www.omnimap.com in the US and the Map Shop (www.themapshop.co.uk) or Stanfords (www.stanfords.co.uk) in the UK if you prefer to purchase them beforehand. Kompass maps (www.kompass-italia.it) also cover the Dolomites.

Plenty of good road maps can be found – the Touring Club Italiano 1:200,000 Trentino Alto Adige is hard to beat.

Dos and don’ts

It’s better to arrive early and dry, than late and wet

Maxim for walkers

Find time to get in shape before setting out on your holiday, as a good level of fitness will maximise your enjoyment. If you’re not exhausted, you will appreciate the wonderful scenery more and react better in an emergency

On the trail find your pace. If you have to keep stopping to catch your breath, you’re going too fast

Don’t be overly ambitious; choose routes suited to your capacity and read the walk descriptions before setting out

Get into the habit of leaving word at your hotel of your planned route, or signing the hut register if staying in a rifugio, as this may be helpful if you don’t turn up when expected

Don’t set out late on walks and always keep extra time up your sleeve to allow for the possibilities of any detours due to collapsed bridges, wrong turns taken and missing signposts along the way. Plan on getting to your destination early in hot weather, as afternoon storms are not uncommon. As a general rule, start out early in the morning to give yourself plenty of daylight

Stick with your companions and don’t lose sight of them. Remember that the progress of groups matches that of the slowest member

Avoid walking in brand new footwear as they may cause blisters, but leave those worn-out boots in the shed, as they may prove unsafe on slippery terrain. Three quarters of mountain accidents are caused by slipping. Choose your footwear carefully!

Don’t overload your rucksack and remember that drinking water and food add extra weight

Carry extra protective clothing as well as energy foods for emergency situations. Remember that in normal circumstances the temperature drops an average of 6°C for every 1000m you climb

Check the weather forecast if possible – tourist offices and hut guardians are in the know. For the Südtirol see www.suedtirol.info, for Trentino www.meteotrentino.it and for the Veneto www.arpa.veneto.it. Never set out on a long route in adverse conditions. Even a broad track can become treacherous in bad weather, and high-altitude terrain enveloped in thick mist makes orientation difficult. An altimeter is useful – when a known altitude (such as that of the refuge) goes up, this means the atmospheric pressure has dropped and the weather could change for the worse

Please carry rubbish back to the valley, where it can be disposed of correctly; don’t expect hut or park staff to deal with it. Even organic waste such as apple cores and orange peel is best not left lying around, as it upsets the diets of animals and birds

Be considerate when making a toilet stop. Keep well away from watercourses, don’t leave unsightly and unhygienic paper lying around (bury it) and resist any temptation to use abandoned huts or rock overhangs; in bad weather these could serve as life-saving shelter for other people!

Collecting flowers, insects or minerals is strictly forbidden, as are fires

Learn the international call for help – see below. DO NOT rely on your mobile phone, as there may not be any signal. Refuges have landlines and experienced staff can always be relied on in an emergency. In electrical storms, don’t shelter under trees or rock overhangs, and keep away from metallic fixtures

Lastly, don’t leave your common sense at home

The old Felizon rail bridge (Walk 5)

Emergencies

For medical matters, EU residents need a European Health Insurance Card (EHIC). Holders are entitled to free or subsidised emergency treatment in Italy, which has an excellent national health service. UK residents can apply online at www.dh.gov.uk. Australia has a similar reciprocal agreement – see www.medicareaustralia.gov.au. Other nationalities should take out suitable equivalent insurance. In any case, travel insurance for a walking holiday is also strongly recommended, as the costs of rescue and repatriation can be considerable. Members of Alpine clubs are usually covered, but do check before you depart.

The following may be of help should problems arise.

Polizia (police) Tel 113

Tel 118 for health-related emergencies including ambulanza (ambulance) and soccorso alpino (mountain rescue)

‘Help!’ in Italian is Aiuto! (pronounced ‘eye-you-tow’). Pericolo is ‘danger’

Should help be needed during a walk, use the following internationally recognised rescue signals: SIX signals per minute either visual (waving a handkerchief or flashing a torch) or audible (shouting or whistling), repeated after a pause of one minute. The answer is THREE visual or audible signals per minute, to be repeated after a one-minute pause. Anyone who sees or hears a call for help must contact the nearest source of help, a mountain hut or police station for example, as quickly as possible.

These hand-signals could be useful for communicating at a distance or with a helicopter.

Both arms raised diagonally

help needed

land here

YES (to pilot’s question)

One arm raised diagonally, one arm down diagonally

help not needed

do not land here

NO (to pilot’s question)

Using this guide

The 50 walks in this guide have been selected for their suitability for a wide range of holidaymakers. There is something for everyone, from leisurely family strolls to strenuous climbs to panoramic peaks for experienced walkers. Each walk has been designed to fit into a single day. This means carrying a small rucksack and being able to return to comfortable hotel accommodation at day’s end. That said, many walks become even more enjoyable if stretched out over two days, with an overnight stay in a rifugio (see Accommodation). For more ambitious walkers, 25 multiple-day walks can be found in the Cicerone guide Walking in the Dolomites, while Trekking in the Dolomites: Alta Via routes has six amazing long-distance routes.

Each walk description is preceded by an information box containing the following essential data:

Spiky Croda da Lago and the Lastoni di Formin (Walk 19)

Distance This is given in both kilometres and miles.

Ascent and Descent This is important information, as height gain and loss are a further indication of the effort required and these figures need to be taken into account alongside difficulty grade and distance when planning the day. A walker of average fitness will usually cover 300m (about 1000ft) in ascent in one hour.

Difficulty The difficulty of each walk is classified by grade, although adverse weather conditions will make any route more arduous. Even a level road can be treacherous if icy.

Grade 1 – an easy route on clear tracks and paths, suitable for beginners

Grade 2 – paths across typical mountain terrain, often rocky and with considerable ups and downs, where a reasonable level of fitness is preferable

Grade 3 – strenuous, often entailing exposed stretches and extra climbs. Experience and extra care are recommended

Walking time This does not include pauses for picnics, views, photos or nature stops, so always add on a good couple of hours when planning your day. Times given during the descriptions are partial (as opposed to cumulative). If following a route in the opposite direction, allow roughly two thirds of the time if it’s an ascent that you’re descending, and about 1½ times more for a downhill section that you’re climbing up.

Note A handful of walks described have stretches across rock faces aided by anchored cable. While they are not strictly climbing routes necessitating special equipment, there are rules that need to be followed:

Always keep away from iron cables and rungs in bad weather and if a storm is brewing, as the fixtures attract lightning

Avoid two-way traffic on a single stretch of cable, as it can become awkward and consequently dangerous if you try to pass people. It’s common sense to wait until those approaching from the opposite direction have passed before you proceed, to avoid any added strain on cables

Within the walk descriptions, ‘path’ is used to mean a narrow pedestrian-only way, ‘track’ and ‘lane’ are unsurfaced but vehicle-width and ‘road’ is sealed and open to traffic unless specified otherwise. Compass bearings are in abbreviated form (N, S, NNW and so on) as are right (R) and left (L). Reference landmarks and places encountered en route are in bold type, with their altitude in metres above sea level given as ‘m’, not to be confused with minutes (abbreviated as min). 100m=328ft.

Place names in the Dolomites often come in trilingual versions: the old German names for the northern region (the former Tyrol), along with their Italian translations and the recently re-introduced ancient Ladin versions. For the purposes of this guide the Italian version has been given preference so as not to weigh down the text unnecessarily; other names have occasionally been used as well where deemed useful. There is an Italian–German–English glossary of topographic and other features at the back of this guide in Appendix B.

The vast San Martino Altipiano with the cablecar station and Rifugio Rosetta (Walk 46)