Читать книгу Japanese Art of Miniature Trees and Landscapes - Giovanna M. Halford - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление| 1 | INTRODUCTION |

THE ART OF GROWING AND caring for miniature trees is one which may be enjoyed practically anywhere in the world, although it has reached its apex in Japan. Owning a particularly fine bonsai, as the Japanese call these trees-the word is written with characters meaning "tray" or "pot" and "to plant"-is a responsibility, not to be undertaken lightly. A Japanese who owns bonsai has nearly always taken the trouble to turn himself into an expert; he has studied the art and is probably acquiring a collection of these little masterpieces. He gives up a good deal of his time to their care, belongs perhaps to a bonsai society, allows his best trees to appear in exhibitions, and attends the annual auctions, sometimes to buy, sometimes to sell, sometimes just to "study form." He may well have inherited his most valuable trees from his father and grandfather, for bonsai lovers, like bonsai growers, are both born and made, artists and craftsmen with a long tradition behind them. The all-too-common practice among Western visitors to Japan of buying a bonsai and then allowing it to die through neglect or ignorance is shocking to the Japanese. They know that the dead tree, flung on the rubbish heap with a rueful "Oh, well, it wasn't so very expensive anyway," represents many years of loving care by some unknown gardener, whose grandfather may have sown the seed.

But the amateur should not be discouraged by this talk of many years and heavy responsibilities involved in making and caring for a perfect specimen. Perfection is rare, and enjoyment does not depend on it; and, as will be pointed out, there are short cuts and "tricks of the trade" by which a handsome bonsai can be created in months rather than years. It is certainly not difficult to learn at least the basic rules which will keep a bonsai alive. With a little trouble anyone who loves plants can give it proper attention, water it sufficiently, keep it free from disease, do simple pruning, and even change the soil when necessary. The smallness of the bonsai is so wonderful that many people believe that there must be some mystery about them, some special treatment known only to the initiates so that, as one often hears, "bonsai always die in two or three months in a Western house." But this is not the case. The authors hope that this be ok will help Western people who own bonsai to care for them and increase their own enjoyment. They also hope it will encourage those who like gardening to experiment in making and training their own miniature trees.

It might be difficult for a person with absolutely no experience in gardening who lives in an apartment in a city to grow a bonsai from seed and train it, but there is no reason why he should not care for a ready-made one successfully, provided he has a convenient fire escape or window box for the tree to live on and can take it from time to time to a reliable nursery for advice and inspection. But the man or woman who is accustomed to a garden, who knows about seedlings and shrubs and young fruit trees, will find from this book that the technique of growing bonsai is largely an adaptation of what he knows already. If he is prepared to embark upon an undertaking-no longer, after all, than the development of a mature apple orchard and in many cases much shorter-which will require a good deal of patience, the performance of little, fiddling jobs which may not take more than a few minutes of his time every day but which; must not be neglected, then he may enjoy the satisfaction of possessing a treasure of his own making. The technique is here in this book.

What we cannot teach 'by rule of thumb, although we have tried to indicate the fundamental principles, is the art which make!; the bonsai perfect. The final beauty of the bonsai lies in its training, and each person must see for himself just how the tree can be displayed to greatest advantage, whether its form should be austerely classical or gracefully cascading, whether this branch spoils the symmetry or the addition of a rock or tiny shrub may not give balance to the whole. The choice of pot, the position of the tree in the pot, the angle at which the trunk is set, the way in which the exposed roots are arranged, all these go to make the masterpiece.

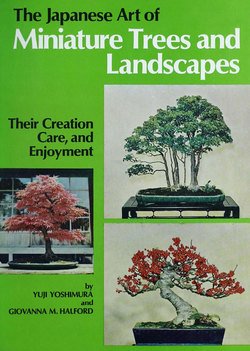

Color Plate 2. Japanese persimmon. Informal upright style. 2'2". About 30 yrs. Produced from a seedling and potted about 20 yrs. ago. Glazed Chinese pot.

Color Plate 3. Japanese millettia. Informal upright style. 1'3". About 15 yrs. Produced from a cutting or by dividing. Glazed Japanese pot.

Color Plate 4. English holly. Informal upright style. 11". About 35 yrs. Produced from a seedling or cutting or by layering. Glazed Chinese pot of Kuang-tung wore. the color contrasting harmoniously with the red berries, which remain for most of the winter.

In this book there are numerous photographs of finely trained bonsai, which will help the novice to "get his eye in" and realize what to aim at. They will also help the owners of full-grown bonsai to keep their trees in proper shape when they show a tendency to grow out sideways or otherwise spoil the line which art has so carefully given them. It is, in fact, a good idea to photograph a newly acquired bonsai for reference in years to come, although this does not mean that the shape of a trained bonsai cannot be improved. The owner may find, as he studies these illustrations, that by planting his tree at a different angle or training a branch to fill an ugly hiatus he can give the whole a more satisfying beauty.

Owners of bonsai should always try to have more than one tree. The temptation to keep the tree in the house so as to enjoy it and see the enjoyment of others is almost too strong for most Western people. But if there are several which can be brought into the house in rotation they will not suffer. It is also worth while to arrange a suitable setting for the bonsai, a special place in the room where it will look its best. With this in mind we have made some suggestions at the end of the book as to how a substitute for the Japanese alcove can be arranged in a Western room. Bonsai have such a very Japanese look about them, even when grown by someone who is not Japanese, that there is good reason for adapting the room to the tree rather than the tree to the room.

Until the turn of the century bonsai had never been seen outside Japan, and their first appearance, at an exhibition in London in 1909, created a sensation. The idea of age with smallness is fascinating and has led many Western people to give undue importance to the age of a tree. They tend to expect a bonsai to be hundreds of years old and are disappointed to learn that it is not. They forget that the most important thing about a bonsai is its beauty. Many people do not realize that the creation of bonsai is, for Japan, a comparatively new art. A good deal of confusion comes from the fact that certain trees are said to be six or eight hundred years old, and Western people assume that the practice of dwarfing is older than that. This is not the case. These very old trees have probably been entitled to the name of bonsai for less than half that time, although their age is fully documented. The Japanese have always loved miniature things, and since very early times naturally stunted trees have been collected and treasured. But these are not bonsai; they are classified by the Japanese as "potted trees" to indicate that there has been no attempt to improve on nature. The oldest existing bonsai started in this way.

The early history of bonsai is a subject of some dispute and is not important for the- purposes of this book. Certainly by the early years of the Meiji era (1868-1912) the art had become quite well established in its present form. And it was probably during the late sixteenth century, at the close of the Muromachi period (which might be described as Japanese Rococo), that the idea of artificially improving,the shape of potted trees came into existence. At first it was merely a question of training these trees so as to compensate for natural defects, and it may be noted that to this day the most treasured bonsai are still those which are naturally stunted. Potted trees were to be found only in the houses of wealthy nobles, who could afford to pay the price for a thing so rare. But as the idea of improving on nature took hold, gardeners began to realize that it would be possible to create artificial dwarfs from seed or cuttings. These could be produced in quantity and were often as beautiful as the older trees, with a naturalness outrivaling nature, a factor which the taste of the period found particularly appealing. Moreover, there was a new and inexhaustible market for bonsai among the wealthy and cultivated merchant class, then beginning to rival the aristocracy as a patron of the arts.

Thus bonsai came into being. Their creation remains one of the cherished arts of Japan, and the care and patience which go into the making of one miniature tree is infinite. Of course, not all bonsai are exhibition pieces. We have laid some stress on the time and trouble required to create a fully matured tree, but again we emphasize that this should not discourage the novice from trying his hand. It is true that there are no short cuts to perfection, and bonsai growers generally think in terms of months and years instead of days and weeks. But, although to the connoisseur only a fully trained tree is worthy of note, that does not mean that to the grower, and particularly to the amateur grower, the tree is not both beautiful and exciting from its early stages. The very fact that it exists at all, that it puts out leaves and behaves like an ordinary tree, is a wonder in itself. And there are many bonsai of real beauty which have been in training for only three years, or even less.

Not all trees are equally slow in growing, and trees which begin as cuttings or layerings-or, faster yet, as a small and untrained but promising potted tree such as can be discovered at any nursery-have a good start over trees grown from seed. The willow is a particularly good subject for a beginner as a willow cutting takes very easily and is extremely hardy. It grows fast and training can begin as soon as shoots develop-within a month or two of planting the cutting. In two or three years the willow will be a fair-sized tree with graceful drooping branches and can be used very effectively in rock plantings, where it can be made to hang over a miniature pool.

Even if the young tree must stay in its training pot for some years, it has all sorts of charms-some perhaps visible only to the eye of its creator. A tree that is five years old and has still not outgrown its three-inch pot is a triumph. Its shape may not be remarkable, but that will come. The tiny lilac tree grown from a cutting taken ten years ago and now covered with minute clusters of flowers is as much a treasure as the splendid two-hundred-year-old pine whose branches spread so gracefully.

After all, the pine was once a seedling, one among many. It grew into a gawky little sapling, and its tender branches were first persuaded to follow the line which would lend it most beauty when a full-grown tree. For years it received un- ceasing care. Perhaps the first owner never lived to see the completion of his work. His son may have watched the tree develop into a handsome bonsai, worthy of a fine pot. But it is his grandsons and great-grandsons who inherit the full benefit of all this thought and labor and continue the work, pruning the old tree, wiring wayward twigs, watching for signs of disease, and above all enjoying its beauty.

The miniature "Japanese garden" with tiny houses, bridges, people, animals, and the like, which is often seen in the West, is regarded by the Japanese bonsai lover as a rather vulgar object. But the tiny landscapes formed of group plantings and rock plantings belong to quite another category. They have the advantage of making use of young trees and dwarf shrubs which can be easily obtained from a nursery, if they are not available in the reader's own garden, and may be shown with pride within a week or two of their completion. The pleasure of arranging one of these group plantings is enormous. Japanese tend to prefer groups all of one species, but Western people often like to make a "mixed wood" like their groves at home. The little landscape can have a rocky cliff hanging over it or a grotto made from a hollow stone. It can be provided with a "river" of sand or made in the form of a gentle mossy slope which looks like a heath in Lilliput. On the practical side, these arrangements make excellent table centers and, if they consist of evergreens, go far to solve the winter flower problem. The same may be said of rock plantings, in which the pleasure of creating a miniature landscape is enhanced by the search for an interesting stone to build it on.

The bonsai owner finds that his trees ' become part of the family; he has a tendency to gravitate toward them at any spare moment of the day, just to make sure that all is well. Each one has its moment of glory, when it is the favorite child. The plum, quince, and apple follow each other in the spring; the deciduous trees are brilliantly green in early summer; in autumn the maples turn red, gold, and orange; and in winter there is the rich,. dark color of the pines. And even though the maples and the fruit trees stand bare and leafless through the winter months, their owner can still take pleasure not only in the delicate tracery of their branches, but in the strong buds on every twig. Spring never seems far away with these reminders.