Читать книгу That Stranger Next Door - Goldie Alexander - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 8

ОглавлениеEva

The morning after the nameless men brought me here there was a tap on the back door. I unlocked the chain. On the other side was a small, plump woman with short, curly black hair.

'Neighbour,' she said, and pointed next door in case I didn't understand.

I unlocked the chain, opened the door, and looked beyond her. I saw nothing to frighten me; only a stretch of green grass flanked by a wooden fence and criss-crossing washing lines. Petticoats, vests, socks and shirts snapped and writhed in the breeze.

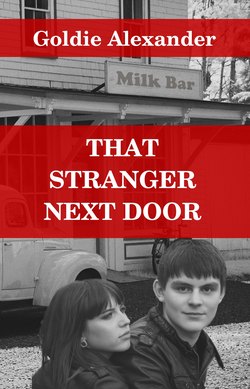

The woman introduced herself as Mrs Esther Cohen. With a little English and many gestures, she explained that her husband ran the downstairs milk bar, then handed me a plate with several slices of home-baked cake. Wonder upon wonders, after a little to-ing and fro-ing, it turned out that she knew a little Russian. She managed to convey in a curious mix of Russian, Polish, and Yiddish (this language being similar to German) that the flourless cake was made with almond meal and eggs.

When I asked how it was that she knew a little Russian, she told me that back in Poland she was forced to study this language; though she quickly added that she had forgotten most of it. For a Jewess, she was friendly, far friendlier than the Jews back home who always kept to themselves unless they had something they wished to buy or sell.

My village held no more than a hundred houses, some even without proper chimneys which made the smoke stain the walls as it forced its way outside through windows and doors. The only way to heat our cottages through the long cold winters was with wood, so the surrounding countryside was treeless. Only the state-owned forest had been left intact.

Yet I remember how, in spring and summer, a riot of poppies, carnations, sunflowers, daisies and violets always made up for the lack of trees. From what I have read in magazines and newspapers, I was able to picture my whole country reduced to a village of narrow muddy streets, the church forming an oblique pattern against the sky, skeletal carts and horses clip-clopping along rutted roads, the few people still living there keeping constant watch for any stranger that dared turn up.

An old man stood half paralysed against a wall, a hunchbacked woman - an elderly babushka - cackled a greeting through her toothless mouth. Chickens pecked and scuttled between houses. But there were no longer any children. Anyone of childbearing age had either left, been deported, or killed.

Before the war my village had been strictly divided between Orthodox Christians and Jews. We had three quarters of the land, the Jews held the rest, though there were almost as many Jews as Christians, and therefore they were forced to crowd together. Though we traded freely, somehow we Christians always seemed to come off worse. It was well known, even amongst us children, that Jews were far too clever for their own good, that they used children's blood to make unleavened bread and had other evil practices too numerous to mention.

Only later, much later, did I begin to wonder how much of this could have been true? Certainly they were clever traders, but as they weren't allowed to own any land, this was hardly surprising. And even if any of those stories had some basis in fact, surely they didn't deserve the treatment they received from both the Germans and the Russians.

It was only long after I left, that I discovered what did happen after the Germans arrived; learnt that there is a large pit outside the village where many, many bodies are buried. Even sadder, after the war those few Jews that hid in the forest and survived, were regarded with suspicion by our communist leaders and sent to die in the Siberian gulags.

Later that afternoon Esther's daughter, Ruth, turned up. Taller and slimmer than her small round mother, but with the same spectacular shock of curly black hair, her neat features and smooth olive skin were very attractive. One day she could be quite beautiful. Though she presented a well-behaved exterior, she had a way of flicking a lock of hair that hinted at an unexpected yet hidden boldness I found interesting.

First, I insisted she never divulged my presence to anyone, not anyone; which she promised she wouldn't. She seemed clever enough to handle any errand I might need. I was hoping the letters she posted would reach the village where Mamushka and my little sister Anushka lived. I gave her two pound notes, careful instructions how to spend them, and told her to keep the change.

I was hoping she could also speak a little Russian, but in this I was disappointed. In Australia, few children knew more than one language. Nevertheless she did speak Yiddish, so we resorted to some simple German and my limited English. After she ran my few messages, I found her to be intelligent and pleasant. She kept reassuring me that she would keep my presence a secret. Oddly enough, I believed her.