Читать книгу That Stranger Next Door - Goldie Alexander - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 4

ОглавлениеRuth

This morning Leon jumped onto my bed and bounced on me until I agreed to wrestle him back. Only when he was nearly suffocating under the blankets, could I get him back to his own room.

Sometimes I got fed up with having to look after him. It was no one's fault; Mamma and Papa worked sixteen hour, six-day weeks, so there was only me. Maybe if Leon wasn't so independent it would be easier. Last week in the park - where admittedly I was deep into a novel - he took off without me noticing. It took me ages to find him and I was so angry, I yelled at him. 'Do that once more, I'll tell Papa and he won't let you come here again.'

Then, of course, all the thanks I got for taking him to the park was him sulking all the way home.

After school today Mamma had arranged to take me and Leon to visit the Feldensteins. She came into my room to ask why I wasn't dressed to go out?

'Mamma, I've too much homework,' I wailed. 'Can't you take Leon without me?'

Mamma's hat was already on and she was pulling on her gloves. 'But Daisy will be expecting you.'

'Yeah, well.' I shrugged. 'I'm sure she won't miss me.'

Mr Feldenstein has pots of money and all Daisy could talk about was shopping, and how the saleswomen looked down on her, and how she bought stuff she didn't really want just to see their faces change from nasty to 'can't help you enough'. I didn't think she had any other friends except me, and I guess that's really hard, so I should be kind to her. But last weekend my best friend Nancy Bloom loaned me her copy of Rebecca and she wanted it back as she'd promised it to someone else as soon as I could return it.

Back at Elwood Central, Nancy and I were never apart. But these last two years, what with her attending a co-ed University High, and me at the girls-only St Margaret's, our lives were utterly different, though we phoned each other at least four times a week.

Something she mentioned last time we spoke was, 'Did you know that women teachers in state schools have to resign if they want to get married?'

'Really?' My eyebrows shot up. 'What happens to the men?'

'Suppose for them it's okay.'

'That's not right,' I murmured.

'Sure it is,' Nancy said in her 'mother-sensible' voice. 'But there's nothing they can do about it, is there.'

Nancy was always accepting stuff I would fight to the death to change. If I questioned anything too much, she'd act as if I was doing my best to throw her entire world into chaos.

I said, 'Can't being married be a secret?'

'Maybe. But things never stay secret, do they?'

The second tram I have to take to school was packed with St James Catholic College boys, thankfully too busy jostling each other to notice me. But there were no spare seats so I stood opposite a man holding The Argus and read it upside down. Still lots about Evdokia Petrov.

Further down the page I read: 'New Australian mobster chases wife with a knife.'

How horrid for that poor woman. When I tried to read a bit more, the man gave me a sour look and stowed the paper inside his briefcase.

I didn't care. I was back in my favourite daydream, the one where I was already at university studying medicine. Whenever this came up at home, Mamma snapped, 'Why can't you be happy as a teacher or a stenographer? They're perfectly good professions until you get married. If you trained as a teacher you would pick up a bursary that will pay for your further education.'

'Then I'd be sent to the country,' I retorted. 'You wouldn't like that either. You think I wouldn't be any good as a doctor. But don't you remember how I bandaged Papa's finger when he cut it almost to the bone? And what about when old Mr Collins fainted? Everyone panicked, but I knew to hold up his head, make him sip water and ask someone to phone for an ambulance.'

She sniffed disapprovingly. 'Who will marry a girl that examines naked men's private parts?'

'Aren't nurses women as well?'

'Nursing is no career for a well-brought-up Jewish girl,' she tartly responded. 'God knows what those girls get up to in the nursing homes.'

How was I supposed to answer that?

'If I don't get into medicine,' I shouted, 'maybe I'll go to Israel and join a kibbutz. They're always looking for volunteers. They might even let me ride a bike-'

'And another thing,' Mamma continued as if my threat meant nothing, 'why can't you be friendly with Daisy? As you're both going to private schools, you have a great deal in common.'

'Like what?' The last thing I needed was Mamma choosing my friends. 'Daisy only talks about shopping.'

'She's polite, which is more than I can say about my own daughter.'

'Maybe she's polite because her mother doesn't tell her who should be her friends.'

Mamma's chin lifted indignantly. 'I only advise you for your own good. It's time you started taking other people into consideration.'

'Being friendly with someone I don't like isn't taking me into consideration.'

As usual all these arguments between us only stopped with her walking away, muttering, 'You never think of anyone but yourself'.

I always spent morning and lunch breaks with Kate Howell's crowd. When I first got to St Margaret's Anglican College I was mostly ignored. It seemed that winning this scholarship would keep me lonely and miserable forever. What happened to change things around was one day when our teacher was absent I noticed Kate Howell was having trouble answering a math problem.

I sidled into the empty seat beside her. 'Need some help?'

She nodded furiously.

This wouldn't have been enough for her picky crowd to include me. What made the difference was that after we chatted a while, Kate discovered I loved basketball as much as she did and that I was even prepared to play goalie, which everyone knows is a team's worst position. Given Kate's influence, which is strong enough for her to always play centre, her crowd finally took me under their wing.

Kate was tall, slim, and fair, with eyes the same shade of blue as the sky at sunset. Her close friends, Anne, Denise, Marcia and Lizzie, were equally tall and skinny, with long straight hair, ranging in colour from mousey-brown to blonde.

Given I have dark eyes, black curly hair, olive skin and wear size C brassieres, I felt utterly different. They often commented on how lucky I was to have a grown-up body and how much they wanted their breasts to grow like mine, and how they despaired that they ever would. So even though they tried to make me feel like I was one of them, sometimes I wondered if I really was. But if I lingered too long on feeling like an outsider, I would probably become one, so I tried to avoid thinking this way as much as possible.

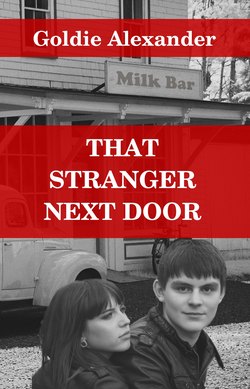

Kate's grandparents ran a station in Queensland as big as Great Britain. 'They need this much land,' she said, 'because it's one animal to one acre.' Her family also owned a house at Portsea. When the family were in Melbourne they lived in a double-story Victorian mansion with three separate living areas, a billiard room, six bedrooms, goodness knows how many bathrooms, and a butler's pantry. Whenever Kate invited me home, Mrs Howell was always very polite. But I could tell she wasn't keen on her daughter being friendly with a Jewish scholarship girl whose parents happened to run a milk bar.

Today, Miss Brown made us wait until after last bell before handing back our science projects. Her writing was so tiny it was hard to read. As I walked towards the tram trying to decipher: Good work, but need to explain Section B more fully- I walked straight into a bike, staggered and fell.

My right knee hit the pavement with a dull thud. Ouch, that really hurt!

As I tried to get up, I dropped my bag.

A boy hopped off his bike, picked up my bag and handed it to me. 'Sorry about that,' he said. 'I didn't see you.'

I rubbed my knee. 'No, no, my fault,' I muttered. 'I wasn't looking.' My voice trailed away. I knew I was flushing beetroot.

Why was I always this clumsy? Why didn't I look where I was going?

The boy peered at me more closely. 'Sure you're okay?'

I limped to a nearby fence, sat down, and examined my knee. Blood was starting to seep through the torn stocking. I searched through my pockets for a hankie, but he handed me a wrinkled one, covered in ink stains.

'Thanks,' and because he still looked concerned, I hurriedly added, 'Guess I'll live.'

'You'd better or I'll be had up for murder.' A smile displayed a chipped front tooth. 'Oh, I'm Patrick. Patrick Sean O'Sullivan. Sorry about that.' He peered at my knee. 'And you are?'

'Me? Um, Ruth,' I said still trying to staunch the blood.

Groups of kids clattered past like chattery parrots. Patrick leant his bike against the fence and settled beside me. As I kept dabbing, I had time to take him in. Nice was the word that sprang to mind. Nice suited this boy. He had lovely cheekbones and a fine jawline. He was a head taller than me, with a shock of brown hair trying to escape from under his school cap, and his eyes were the same intense blue as Kate Howell's. His face was long and thin, his thick eyebrows the same colour as his hair, his chin and cheeks were only a bit pimply, and his lower lip slightly pouty. That loose-limbed build told me he played lots of sport.

'Ruth.' His lips twitched as if about to break into laughter. 'Ruth what?'

His grin was so infectious, I couldn't help smiling back. 'Ruth Adele Cohen.'

'Ruth Adele Cohen.' He focussed on my knee. 'Looks really sore. Where do you live? How about I dink you home?'

Oh. Being dinked would mean confessing to a total stranger that I didn't know how to balance on a bike.

I was sure my face was scarlet. 'Look, I'll be fine. It's just a scrape.'

His registered doubt. 'If you say so.'

I tried to return his hankie. 'Keep it, Ruth,' he said climbing back on his bike. 'Give it back next time we meet.'

Next time? I watched him ride away. It was only then, I realised I'd forgotten to be shy, only embarrassed at being clumsy. Mostly however, I was thinking: he wants to meet me again.

In spite of my sore knee, I was walking on air.

When I got home, for some reason I couldn't quite explain even to myself, I told Mamma I'd tripped over a tree root and fell.

'Tch-tch. You are so clumsy, Ruth.' She examined my knee, then busied herself sponging it with warm water and soap, dabbing it with Mercurochrome and covering it with plaster. By now my leg was too stiff to do anything except tackle a mountain of homework.

But first, I limped into the bathroom to wash Patrick's hankie. The blood came out, but the ink was indelible. I took it into my room where I draped it over a louver to dry.

Back in the kitchen, and still thinking about Patrick, I helped myself to a slice of Mamma's almond cake. I pictured meeting him again. This time I was far less awkward, far more in control.

This time I knew how to speak to a handsome boy without looking stupid.

A few minutes later, Mamma came up from the shop. 'Ruth, Eva our new neighbour needs you to run some errands. Is your knee too sore?'

'No, I'm fine.' I stood slowly. 'What's her surname?'

Mamma shrugged. 'She introduced herself as Eva.'

I limped next door and knocked. The woman called Eva undid the chain, peered out, then unlocked and opened the front door. She was in a pink woollen dressing gown and slippers. This close, I realised she was about the same age as my mamma.

'Um…' I tried looking down the passage to see if anyone else was there. 'You've got messages you want me to do?'

She nodded, then to my astonishment, she pulled me inside and slammed the door behind me. Her hallway was dim; no light in any room. A quick glance into her bedroom showed every blind was drawn. The sitting and dining rooms were equally dim.

'You Ruth?'

I nodded.

'Ruth, me Eva. You Mamushka say you do message?'

I nodded again. Those deep shadows under her eyes told me she was a bad sleeper.

'You spik Russki?'

'Ya pan-ee ma-yu-pa-rooski - very little,' I told her. 'Just a few words.'

Openly relieved, she grabbed my hand and shoved four letters into it. A quick glance told me the addresses were in Cyrillic, a script I can't read. 'Post.' She thrust two one-pound notes into my other hand. 'Post letters.'

I stared at the notes. 'Too much,' I said, all my Russian used up. I tried French. 'Tres… excessive.' I shook my head, gesticulated.

She nodded as if she understood. 'You keep rest.'

My chin dropped. 'No, no. I'm sure that's too much.'

But Eva was already gently shoving me out the door.

I took her letters to our post office half a block away. This late, the queue almost reached the door. When I finally got to the counter, the postmistress looked at the envelopes and then me with equal suspicion. 'New Aussie, I suppose,' this sounding more like 'bloody foreigner'. But she slowly stamped the letters and handed over the change.

I didn't bother counting the coins until I was outside. I was left with nine shillings and threepence. I placed the coins in my pocket where they made a satisfying jingle. It was enough for a new paperback; or two second-hand ones.

How could Eva fling money around this easily? Why did she move into the next-door flat at midnight? Who were those people that came with her? Why was her flat so dark, as if no one really lived there? Why didn't she go down the street herself? Why was she so secretive? Who really was that stranger next door?

It was later that night, after I'd completed my homework, eaten dinner, read Thomas the Tank Engine to Leon for the umpteenth time and gone to bed myself that the answer hit me.

This mysterious woman called 'Eva' must be Evdokia Petrov.

She looked like the woman in that photo, the one the police dragged off the plane at the last minute in Darwin. I thought back to the photo in The Argus. Both Eva next door and Evdokia were of average height, and full breasted, even a bit plump. Both have straight light brown hair worn collar length.

The men I had seen with Eva looked like they could be plainclothes police, though I wondered about the tall skinny woman. And my neighbour was obviously frightened of anyone knowing where she lived, otherwise why behave so secretively? To top it off, she had more than enough money to throw away in tips.

It all added up.

I sat up in bed and hugged my knees. We had a real-life spy novel happening next door.