Читать книгу That Stranger Next Door - Goldie Alexander - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 1 MELBOURNE

APRIL, 1954

ОглавлениеRuth

Just after midnight I was woken by feet clambering up the rear staircase. Curious, I crept down the passage, through the kitchen onto the wooden landing. From here I could look into next door's windows. A light went on and a blind shot up.

I saw two women and two men, their faces half hidden by hats, their heads together as if deep in conversation. They must have felt someone eyeing them, because the blind came back down.

Half frozen and shivering, I dashed back down the passage, jumped into bed, and burrowed under the blankets. Ten minutes later, I heard more footsteps downstairs. My room, an enclosed balcony overlooking Brighton Road, has louvered windows. I sat up to peer between slits, and watched two men, but only one woman, climb into a car with darkened windows.

The car took off down the street.

This late, there was hardly any traffic. Above the outline of distant buildings, a quarter-moon slid behind a cloud; and a cat, skulking along the pavement, receded into the shadows.

I slid back under the blankets and snuggled into my pillow. Next time I woke it was time to get up and dress for school.

Fridays, I was always home just after three-thirty. Mamma was cooking dinner and my four-year-old brother Leon kept getting in her way so she asked me to take him to Blessington Gardens.

He insisted on riding his tricycle and it took me ages to get him there. Then he refused to leave. 'Want more swing.' His voice was thin and high. I brushed tanbark off his clothes. 'Want more swing,' he whined until I wanted to shake him.

On the other side of the playground, an old woman walking past us paused to take his tantrum in.

'Listen Leon,' I bargained. 'If you come right now, I'll read you an extra story at bedtime.'

Bug eyed, he stared at me suspiciously. 'Promise?'

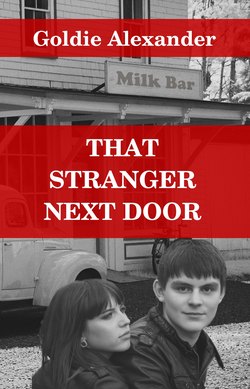

'Promise.' This agreed, we ambled through the park gates and past a row of privet hedges. Cars, trucks and bikes whizzed past, the noise only outstripped by the rattle of passing trams. Five minutes later we reached Papa's milk bar. Above the milk bar were two flats. Our family lived in the one on the right.

While Leon pedalled along the footpath, his long dark curls waving in the breeze, I settled on the steps where I could keep one eye on him, the other on the flat next door.

Last night two men and two women turned up. Two men, but only one woman, left. This meant one woman stayed behind. Curious, I hung around until sunset hoping she would come out. When she didn't, and the blinds remained drawn, and my step got cold and hard I took Leon back upstairs.

After the Shabbat candles were lit and the Kiddush cup blessed, we settled down to eat. All through the meal, the grown-ups didn't stop talking about the news of that day. A Russian diplomat, Vladimir Petrov, had decided to stay on in Australia.

Papa called it 'defecting'.

Because Mr Petrov didn't tell his wife Evdokia what he'd planned, the KGB tried to force her back to Russia. There was a big fuss in the newspapers and on radio as no one thought she should be forced to leave unless she really wanted to.

The front page of The Argus showed her being hustled onto the plane by two Russian agents; and her losing a shoe.

At the very last minute, in Darwin, our police dragged her off the plane.

It was a terrific spy story, even better than The Dam Busters. Or the other one that Paul Brickhill wrote, The Great Escape. And it was real and happening right here in Australia!

Dinner over, Mamma asked me to clear the table and start washing up. Through the rattle of cutlery, I heard bits of my parents' conversation with my grandfather:

'…reds under the beds, like in America.'

'…movie stars forced to admit they belonged to the Communist party and name anyone they saw at a meeting.'

'Why are we hiding Evdokia Petrov?' Zeida rumbled.

I wiped my hands on my apron and went into the dining room to ask in Yiddish - at home we only spoke Yiddish, 'What will happen to her?'

The grown-ups turned as one person to stare at me. Mamma said, 'I expect ASIO will hide her somewhere.'

I went back to the kitchen and continued stacking plates, as the grown-ups kept talking.

'…now Menzies will bring in his anti-communist laws,' Zeida's voice rose. 'Anyone connected to a left wing group will be targeted.'

'I once belonged to the Communist Party,' Papa reminded him. 'Only my membership ran out fourteen years ago.'

I stopped rinsing glasses to listen properly.

Mamma said, 'I don't understand why the Russians want her.'

'Maybe they think she's hiding secrets,' Zeida growled.

'It will take very little to start another round of anti-Semitism,' Papa said dryly. 'So many Jews joined the Australian Communist Party.'

'Trying to outlaw communism is all about trying to stop our right to free speech,' Zeida grunted.

'What can they do to us that hasn't already happened?' Mamma wailed. 'Our children don't realise how lucky they are.'

Grown-ups rarely talk about the Holocaust, at least not in front of us children, as if they're embarrassed that it ever happened; as if they're almost responsible for it themselves. But like a giant golem it always lurks in the background. A photo taken in Auschwitz Camp shows a group of children seated cross-legged on the ground. One girl looks so much like me she could have been my twin. I'm sure she didn't survive, not when so many people were shot and gassed.

Would I have been as brave as Anne Frank? Or would I have crumpled under so much terror?

Still busy shoving forks and knives into drawers and plates into cupboards, I pictured what was happening in the next room. I knew Leon would be in his favourite place under the table playing with his toy train; Papa would appear to be relaxed, his bald spot shining under the overhead light; Zeida would be hiding his thoughts behind his iron-grey beard and grumpy manner. But Mamma's face would be tight with worry, even though Papa would keep assuring her that 'What happened in Europe will never happen again.'