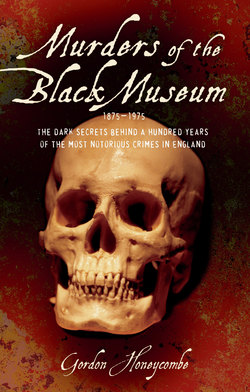

Читать книгу Murder of the Black Museum - The Dark Secrets Behind A Hundred Years of the Most Notorious Crimes in England - Gordon Honeycombe - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

WILLIAM SEAMAN

ОглавлениеTHE MURDER OF JOHN LEVY, 1896

Murder is often the outcome and fatal climax of a life of squalor, deprivation and crime. It as if the criminal involved becomes in time so indifferent to his fate, to other people and to life itself, so desperate and despairing, that he takes another person’s life to bring his own miserable, meaningless existence to an end. Seaman’s execution made history of a sort as he was one of three men hanged in the last triple execution carried out at Newgate Prison in 1896.

William Seaman was moved to commit a double murder by bitter feelings of hatred and revenge. He was said on his arrest to be a ‘stoutly built man of middle height’, with dark-brown whiskers, moustache and beard, and the appearance of ‘a Russian Pole’. Said also to be a lighterman and ‘diver’, he was a convicted felon, aged forty-six, calloused by years of base and brutal living, in prison and out. He allegedly told another convict during his latest incarceration: ‘There’s a bloody fence and his whore at Whitechapel that owe me £70 on a deal. I’m going to their place for the money when I get out, and if the old bugger squeals at paying, I’ll put his light out sure enough.’

That fence was a Jew, John Goodman Levy, aged seventy-five, who lived in a house on the corner of Turner Street and Varden Street, halfway between the sites of Jack the Ripper’s first and third murders, committed in 1888. The area, less than eight years after the Ripper murders and in the year before Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, was still a centre of seething criminal activity, of prostitution, pawn-broking, thievery and insalubrious pubs. Jews thrived locally with second-hand clothes and money-lending businesses, and as pawnbrokers and fences (receivers of stolen goods), though they conducted their lives and occupations, including crime, with more acumen than their neighbours, and with more profit and success. Such a one was old Levy, a retired umbrella-maker with crippled hands. ‘Especially the right,’ according to his stepson, Jacob Myers. ‘Owing to the use of shears in his business.’ Mr Myers, another umbrella-maker, who lived in Bow, also attested to the fact that Levy was ‘very deaf’ and ‘too good and kind’ for anyone to bear him any ill will. Myers and Levy had been in business together until December 1895, when the partnership was dissolved.

The last time Mr Myers saw his stepfather alive was in Levy’s home at 31 Turner Street on the afternoon of Thursday, 2 April 1896. The following night, Levy had a supper party in his house, which was attended by three women: Mrs Annie Gale, aged thirty-seven, who had been Levy’s housekeeper for about eleven years and lived on the premises; her sister, Mrs Alice Weiderman, the wife of a walking-stick carver, who lived in Battersea; and an elderly cousin of Mr Levy, Miss Martha Laughton, who was somewhat deaf and lived nearby, at 35 Turner Street. She and Mrs Weiderman both left the house about 9.45 pm that Friday night, after Miss Laughton had accepted Levy’s invitation to lunch with him the following day. It was the Easter Bank Holiday weekend and a time for visits by family and friends.

On the morning of Saturday, 4 April, Mrs Annie Gale was seen opening the shutters of the ground-floor windows, and she talked to a dairyman, telling him not to forget about leaving some milk on the doorstep on the Bank Holiday Monday. Although it seems that Jacob Myers had until recently rented two rooms in the house, Mr Levy and his housekeeper were now the only occupants. And although Saturday was the Jewish Sabbath, it seems that Levy was not in the habit of attending the local synagogue and stayed at home that morning.

At 1 pm, Miss Laughton, following up Levy’s invitation to lunch that day, called at Number 31 and knocked at the door. There was no response. A small boy from nearby Sydney Street was hovering outside the house and when he approached her she spoke to him. He later told the coroner’s court what he presumably told Miss Laughton, that he had gone to the house earlier that morning (on an errand, it seems) received no reply to his knocking, noticed that there was no fire in the basement kitchen, and returned home to his mother, who had then sent him back to Levy’s house. After more knocking at the front door, Miss Laughton must have expressed some concern, even alarm, to the small boy at the lack of response within. Both of them continued to hover outside the house, unaware that an intruder had stood for a while on the other side of the front door, debating with himself whether or not to open the door and let the visitors in. ‘If I had,’ as he later said, ‘I would soon have floored them, so as they would not have walked out of that house again alive.’

Some other people would later say that odd sounds from within the house could be heard above the rattle and rumpus of horse-drawn vehicles, carts and people passing up and down, and the clatter of trams in Commercial Road. No doubt some of these sounds were reported to the deaf and elderly spinster by the little boy who, possibly encouraged by her, went off to have a look at the back of the house from Varden Street. While there he saw a man wearing a cap peer at him over a garden wall.

By 1.30 pm Miss Laughton was much perturbed and, going next door, communicated her worries to the couple who lived therein, Mr and Mrs Schafer. William Schafer, who was a tailor, determined to check the back of Number 31. He went into his back yard or garden and placed a ladder against the wall that separated Levy’s yard from his. He climbed up and saw a man inside Levy’s outhouse. Glimpsed by Schafer through a little outhouse window, the man, wearing a cap, was looking or bending down and, said Schafer later, ‘appeared to be doing something with his hands’. Schafer shouted: ‘What are you doing there?’ The man looked up, then ducked down out of sight. Schafer called out again, whereupon the man straightened up, left the outhouse and disappeared into the basement of Levy’s house.

The alarm was raised. Schafer instructed his wife to keep an eye on the back of the house while he went outside, to the front of Number 31. There he told Miss Laughton to fetch the police. By this time a small crowd had begun to gather and the intruder was again spotted out in the yard. When PC Walter Atkinson and another constable, both in plain clothes, arrived, they were taken through the Schafers’ house to their yard, from where the constables gamely climbed over the dividing wall and entered the yard of Number 31.

There was a scullery and a lavatory in the outhouse and there was blood on the scullery floor. Within the lavatory lay Mr Levy in a bloody, crumpled heap, face upwards, his clothing disarranged, his throat cut from ear to ear.

PC Atkinson hurried through the house to the front door, where Miss Laughton was now dispatched to fetch a doctor and Mr Schafer admitted to identify the body. The two constables then began checking all the rooms in the house. Atkinson said later: ‘In the top-floor front bedroom I saw the body of Mrs Gale, who was lying on her back on the floor. The body was lying nearest the door, and I could see that her throat had been cut. There was a quantity of blood at the foot of the bed and some on the bed. The room was in great disorder and boxes had been pulled out.’

Such was his agitation at finding the bodies, he apparently failed to register a ragged hole in the lathe and plaster ceiling, an old brown overcoat on the bed, both covered with fallen plaster, and an iron chisel and a long-bladed, bloodstained butcher’s knife, also on the bed. He rushed downstairs.

Meanwhile, out in the street, someone in the swelling crowd spotted a man on the roof and shouted. At that moment PC Edward Richardson arrived at the scene with PC Wensley and seeing the man on the roof entered the house, leaving Wensley to observe the intruder from below. Pounding up the stairs, he came to the ransacked bedroom, in which Mrs Gale lay dead, saw the hole in the ceiling, got onto the bed, and intent on making an arrest pulled himself up through the hole in the ceiling, into the attic space below the roof. Once up there he stumbled about and slipped and one of his feet broke through the ceiling, making another hole.

Daylight was flooding into the attic from a man-sized hole in the roof. Cautiously clambering out through the hole and on to the tiles, clutching his truncheon, PC Richardson saw a man about 15 yards away, edging along a gutter towards the outer parapet. As Richardson called out to Wensley down below in the street, shouting a warning, the man stepped onto the parapet and jumped. He fell about 40 ft.

Below, the crowd shrieked and scattered as he fell. His fall was partly broken by a little girl, whom he struck and was said later to have slightly injured. Seriously injured himself and unconscious, he was seized by the police. PC Wensley said later: ‘With considerable difficulty the man was got inside the house, and not before his coat had been torn from his back by the excited crowd, who would have lynched the prisoner if it had not been for the police.’ After being examined inside Levy’s home by a doctor, who merely diagnosed a fractured arm, the man was taken in a horse-drawn ambulance to the London Hospital in Whitechapel Road, along with the little girl.

A gold chain, a two shilling piece, a pair of eyeglasses and a gold seal had fallen from the man’s pockets as he was manhandled in the street. These items and some money, amounting to 1s 3d, were gathered up by helpful citizens and the police. Other items found in the man’s bloodstained clothing included brooches, earrings, a gold watch, a jewelled pin and 10s 9d in silver. The jewellery was Mrs Gale’s. A stolen wedding ring and a diamond ring had been worn by Mr Levy. It seems that the murderer was disturbed by Mr Schafer’s shout while he was in the outhouse rifling Mr Levy’s pockets, for a purse containing 9d in stamps, a silver snuff box and a diamond-and-sapphire necktie pin were found on Levy’s body.

Some money and a purse were also found on the roof, as well as a broken hammer and a woman’s cap. The hammer’s shaft had snapped off near the head. The cap, with a hat-pin in it, was Mrs Gale’s. Jacob Myers would later say that she had worn it when she did her housework. Presumably the killer stole it because of the hatpin and then dropped or discarded it on the roof.

The hammer had been used to stun both Mrs Gale and Mr Levy before their throats were cut. It had also been used to make the holes in the bedroom ceiling and the roof. The police discovered that another hole had been made in the roof, from the outside, and there was hole in the chimney breast in the attic. It seems that the killer had tried to effect his escape by breaking through the chimney wall into the Schafers’ house next door. About a dozen bricks had been removed. When this proved to be too difficult and when he was out on the roof, he then tried to break back into the house. But this attempt was foiled when the hammer broke. Weaponless, without chisel or knife and with the police at his heels, he jumped off the roof into the street. Why he never ventured to scale the garden wall and flee into the street or escape through another property is a mystery. Perhaps the agitation and activities of Mr Schafer, Miss Laughton and the little boy had attracted a crowd so quickly and so aroused the neighbourhood that he felt himself to be caught in a trap.

Thousands of people visited the scene of the Whitechapel Murders, as they became known, over the Bank Holiday weekend, and on an overcast Easter Monday 31 Turner Street was added to other popular holiday attractions like the British Museum (6,000 visitors), the National Gallery (11,550), the South Kensington Museums (17,900), Hampstead Heath, Hampton Court Palace, and the Royal Gardens at Kew (50,000 went there that day).

For several days after he regained consciousness, the prisoner refused to reveal who he was, and at the coroner’s inquest, on Tuesday, 7 April, the possibility that the injured man was Mrs Gale’s husband was investigated but dismissed. George Gale, a grocer’s assistant and currently a carman (a van driver or carrier), had separated from his wife about ten years earlier; all their children were dead. So said Mary Clark, a baker’s widow living in Sidney Street and Annie Gale’s mother by adoption. She had viewed the accused man in hospital and was sure he was not George Gale.

At the inquest, PCs Atkinson, Richardson and Wensley gave evidence, as did Jacob Myers, Alice Weiderman, Miss Laughton, Mr Schafer, the dairyman and the little boy (William Whittaker, aged seven). Doctors described the injuries of the two dead persons. Mr Levy’s body, when examined at the house, was still warm. He had died about half an hour before being discovered. Six of his ribs and his skull had been fractured and there were cuts on his head. The wound in his throat was eight inches in length, the ‘windpipe and gullet having been cut right through.’ Mrs Gale had been dead for about two hours. Her skull was fractured in several places and ‘the force used in inflicting the wound in the throat had been so great that the knife had actually cut into the vertebrae.’

In the London Hospital, William Seaman’s identity was eventually revealed, and it was established that he lodged in Claude Street, Millwall, on the Isle of Dogs. He had lived there for some time, and claimed to be engaged in perfecting an invention that he was trying to sell. Two policemen guarded him daily in the hospital ward, occasionally making notes of what he said. These ‘voluntary’ statements were later read out in court. It is not known whether Seaman signed them. But perhaps the Millwall inventor and ex-convict, worn down by pain and weary of his guards’ questions, of his own wretched existence, became careless about what he said.

On the day after the double murders, Constable Hacchus, who had helped carry Seaman into Number 31 after he dived off the roof, was endeavouring to give the patient some milk when Seaman allegedly said: ‘I know what’s in front of me, and I can face it. If a man takes a life he must suffer for it. I don’t value my life a bit. I have made my bed and I must lie on it.’ On 17 April, PC Hacchus was helping a nurse to wash the patient, when Seaman said: ‘Never mind washing anything else, as I shan’t be here long … I don’t want to hide anything, and I shan’t try to. I did it. I’ve been prompted to do it thousands of times. I knew the old man had been the cause of all my trouble, and I would like to kill myself now. I’m sick of life.’

Earlier, on 11 April, PC Bryan was present when Seaman remarked: ‘I suppose old Levy is dead and buried by this time.’ ‘I don’t know,’ PC Bryan replied. ‘I’m glad I’ve done for him,’ Seaman is said to have continued. ‘I’ve been a good many times for the money, amounting to £70, and the old man always made some excuse. I made up my mind to do for him. I’m not afraid of being hanged.’ The next day, Seaman allegedly said, on waking up: ‘If the old Jew had only paid me the £70, the job would not have happened. You don’t know what I’ve had to put up from him. But this finishes the lot …’ On another day he said: ‘I’ve been crushed since I was nineteen years old. I’ve done fourteen years and two sevens.’

On Friday, 1 May, Seaman appeared at the Thames Police Court to be charged. The Times noted: ‘The prisoner was lifted into the Court seated on an armchair and was evidently suffering considerable pain. Seaman, who was undefended, was on Thursday night interviewed by Mr Bedford, solicitor, but declined that gentleman’s service.’

Seaman was charged with larceny, as well as with the two murders. He chose to question none of the witnesses, only asking both PCs Richardson and Wensley, as if to prove their lack of observation: ‘You saw only one hole?’ He complained strongly, however, when the various voluntary statements attributed to him were read out in court. Referring to PC Bryan he said: ‘The whole lot of his statement is a complete fabrication. I never had anything to say to him. Or the other one. They are the last two officers I should speak to. He and his companion were always questioning me. The rest of the evidence by the other witnesses is correct, but there is no truth in this.’ He was then committed for trial.

This took place at the Central Criminal Court by Newgate Prison on Monday, 18 May 1896, a year after the second trial there of Oscar Wilde, convicted of gross indecency (which implied ‘homosexual acts not amounting to buggery’) and sentenced to two years’ hard labour in prison, a sentence that he was currently serving in Reading Jail.

Seaman’s trial was the first of the May sessions in 1896, which were formally opened by the Lord Mayor of the City of London attended by various aldermen, sheriffs and officials. Ninety-one persons were to be tried during the sessions: five for murder, one for manslaughter, two for attempted murder, two for rapes and assaults on girls, one for arson, seven for bigamy, eleven for burglary, eleven for larceny, and seventeen for unspecified misdemeanours. Other charges in fact included forgery, libel, letter stealing, perjury, receiving stolen goods and one robbery with violence.

The judge at William Seaman’s trial was Mr Justice Hawkins. Mr CF Gill and Mr Horace Avery appeared for the prosecution. There was no counsel for the defence, and Seaman turned down the judge’s offer of a barrister to act as a watching brief. He was indicted for the wilful murders of John Goodman Levy and Annie Sarah Gale, but only tried on the first charge.

Mr Gill detailed the prosecution’s case and called witnesses in support. All Seaman did was to refute some of the statements he allegedly made in hospital. These included his own (alleged) account of the murders. Mr Gill said that the accused, on the morning of 4 April and after breakfast at his Millwall lodgings, went out between 8 and 9 am, having a hammer, chisel and knife in his possession. Reading from a statement allegedly made by Seaman and written down by PC Bryan, Mr Gill told the jury: ‘The prisoner said that on that morning he went to the house and knocked at the door. Mr Levy opened it and he walked in. Mr Levy said the girl was upstairs. The prisoner, continuing, said: “I then went upstairs and found her in her bedroom. She then had her dress on and was leaning over the bed. When she saw me she shouted and began to struggle. But I soon stopped her kicking. I then got downstairs and soon put the old Jew’s lights out.”’

Why was Mrs Gale the first to die? And why did Levy apparently do nothing about escaping from the house while Seaman ran up the stairs and killed the housekeeper?

PC Bryan’s statement, which had also been read earlier, at the Thames Police Court, reported that Seaman also said: ‘After the job was finished, I heard someone knocking at the door.’ Whether this was done by the little boy or Miss Laughton was not revealed. As Mrs Gale was surmised to have died some two hours before her body was found (i.e., at about 11.30 am), what was Seaman doing in the intervening time, and where was Mr Levy? It was thought that he had died about 1 pm. Why did he not flee from the house?

If what Seaman is alleged to have said is true, Levy opened the door to him about 11.30. Did an argument then take place, during which Mr Levy was struck with the hammer and left for dead? Did Mrs Gale then appear, see what had happened and run screaming up the stairs to her bedroom, pursued by Seaman? Did she try to put her bed between them, whereupon he hit her with the hammer more than once? Having silenced her, did Seaman, thinking that Levy was dead below, spend some time ransacking the bedroom, and possibly other upstairs rooms, before finding that Levy had disappeared, having crawled away and hidden himself in the outhouse lavatory? Although Levy was ‘very deaf’, it seems inconceivable that he would potter about downstairs, not trying to escape, knowing that Seaman was in the house.

It seems likely that the old man was attacked in the hall of Number 31 and hit by several blows of the hammer. Left for dead, he revived, and despite his fractured ribs and fractured skull was able to drag himself out of the house and hide in the outhouse. Perhaps in his condition he was unable to reach the front-door handle or latch and accordingly headed for the back door of the house, which may have been open, it being a warm spring day. Unable to attract any neighbour’s attention, he then may have locked himself in the lavatory in the outhouse. When Seaman came downstairs, to find that Mr Levy’s body was not in the hall, a trail of blood and the open back door may well have led him to the outhouse, where he cut the old man’s throat.

At the conclusion of the prosecution’s evidence, the accused man, when asked what he had to say to the jury in his defence, instead complained about prejudicial remarks about him in a weekly newspaper. The judge then asked Seaman if he had anything to say with regard to the charge against him. Seaman replied that he had nothing to say and no witnesses to call.

Mr Justice Hawkins, during his summing-up, said that there was no evidence to support the accused’s statement that Mr Levy owed the prisoner £70. The jury found Seaman guilty and he was sentenced to death.

A few days later, on 21 May, Albert Milsom and Henry Fowler were also sentenced to death by Mr Justice Hawkins, and it was decided, probably to save time, trouble and cost, to hang them along with Seaman. These two, in the course of a burglary in Muswell Hill, north London, in February, had battered and killed another wealthy old man in his home. During their three-day trial, Fowler, a heavily built man, had tried to strangle his partner, Milsom, in the dock. So, on the scaffold, Seaman was placed between them. ‘It’s the first time I’ve been a bloody peacemaker,’ he said to the chief executioner, James Billington.

The triple execution within Newgate Prison was carried out on 9 June 1876. Seaman’s weight, reduced by his hospitalisation and physical suffering, had fallen to 138 lb. Indifferent to the exhortations and prayers of the chaplain, Seaman was hanged with Milsom and Fowler at 9 am.