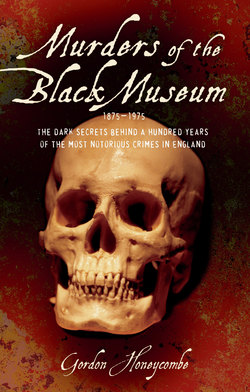

Читать книгу Murder of the Black Museum - The Dark Secrets Behind A Hundred Years of the Most Notorious Crimes in England - Gordon Honeycombe - Страница 22

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление9

MRS DYER

THE MURDER OF DORIS MARMON, 1896

Some sorts of murder in the nineteenth century arose out of the economic and social conditions peculiar to that age. They could never happen now, having been eliminated by social progress and improvements in housing, wages, hygiene and the status of women. Baby-farming was a peculiarity of late Victorian England, when unwanted or inconvenient babies and children, whether illegitimate or merely burdensome, were farmed out to women acting as foster mothers who were paid to ‘adopt’ the infants or to look after them for months or years. Such a surrogate mother was Mrs Dyer, who killed at least seven children, and in her twenty years as a baby farmer may have killed many more. Mrs Dyer also has the distinction of being the oldest woman to have been hanged in Britain between 1843 and 1955.

Anative of Bristol where she was born (in about 1839), brought up and married, Mrs Amelia Elizabeth Dyer was a member of the Salvation Army. She began acting as a midwife and foster mother about 1875 if not before. In 1880, she was jailed for six weeks for running a baby farm in Long Ashton, a village south-west of Bristol. Between 1891 and 1894, she was thrice admitted to lunatic asylums for a month or so – twice, it is said, because she had tried to commit suicide while in prison. In June 1895, she left Barton Regis workhouse with an old woman called Granny Smith and went to Cardiff, where the pair lodged with Mrs Dyer’s married daughter, Mrs Mary Ann (Polly) Palmer, for a few months. During this period, Polly Palmer had a baby that died of ‘convulsions and diarrhoea’ and probably neglect. Her husband, Arthur, was twenty-five and unemployed. Mrs Dyer’s husband, William, whom she had left many years earlier, worked in a vinegar factory in Bristol.

In September 1895, evading creditors and the police, the Palmers, Mrs Dyer and Granny Smith absconded from Cardiff and travelled east to Caversham, a village outside Reading. Here Mrs Dyer, using an assumed name, advertised her trade, and children for adoption or boarding began to arrive. She was assisted in this business by her daughter and presumably by Granny Smith; Arthur Palmer remained out of work.

The ten-month-old baby daughter of a barmaid probably arrived first: the mother, Elizabeth Goulding, paid Mrs Dyer £10. A nine-year-old boy, Willie Thornton, was next, followed by another baby and a girl aged four.

In January 1896, the Palmers moved to London, renting two rooms in Willesden for seven shillings a week and taking with them an infant called Harold, another of Mrs Dyer’s charges. She herself moved from Piggott’s Road to her third address in Caversham, Kensington Road, and using yet another alias, Mrs Thomas, carried on as before. The children she now acquired were Ellen Oliver, aged ten; Helena Fry, who was fifteen months old; and two illegitimate babies of servant girls.

On 30 March 1896, bargemen on the River Thames at Reading fished the body of a baby girl out of the water. She had been wrapped in a brown paper parcel and weighted with a brick. The infant (who was Helena Fry) had been strangled with a tape. On the brown paper was inscribed ‘Mrs Thomas, Piggott’s Road, Lower Caversham.’ The next day, in Cheltenham, Mrs Dyer was paid £10 by Evelina Marmon to take care of her illegitimate four-month-old daughter, Doris.

Miss Marmon, aged 25, a farmer’s daughter and now a barmaid, who had given birth to a baby girl in her lodgings in January 1986, had seen a newspaper advertisement that said: ‘Married couple with no family would adopt healthy child, nice country home. Terms £10.’ Evelina wrote to the woman whose name appeared at the foot of the ad, Mrs Harding, who replied: ‘I should be glad to have a dear little baby girl. We are plain homely people … I don’t want a child for money’s sake, but for company at home and comfort … I have no child of my own. A child with me will have a good home and a mother’s love.’ Evelina Marmon wanted to make the payment in weekly instalments, but Mrs Harding insisted on the £10 being paid in full.

The day after Doris Marmon was handed over to Mrs Dyer in Cheltenham, she and her daughter Polly were at Paddington Station in London, where they collected a baby boy, Harry Simmons, from a Mrs Sargeant, whose maid had given birth to him a year before and then disappeared. Mrs Sargeant was relieved no doubt to dispose of the baby to the kindly elderly woman whose advertisement in the Weekly Dispatch had caught her eye: ‘Couple having no child would like the care of one or would adopt one. Terms £10.’

The following day, 2 April, the two babies, Doris and Harry, who had both been strangled with tape, were dumped in the Thames in a weighted carpet bag.

Two days later, the police at last identified Mrs Thomas of Piggott’s Road as Mrs Dyer of Kensington Road. She was arrested on 4 April. At Reading police station she tried unsuccessfully to kill herself with a pair of scissors and then by choking herself with a bootlace. Her daughter Polly and her son-in-law, Arthur Palmer, were also arrested. ‘What’s Arthur here for?’ asked Mrs Dyer. ‘He’s done nothing.’ The two babies found in her house in Kensington Road were returned to their mothers and Willie Thornton and Ellen Oliver were eventually found other homes. A four-year-old boy who arrived after the arrests was sent away by Granny Smith.

The River Thames was dragged for other bodies, and the decomposed corpse of a baby boy was recovered from the river on 8 April, as was that of another boy two days later. Neither was ever identified. Also on 10 April, the carpet bag containing Doris Marmon and Harry Simmons was retrieved from the river bed. Miss Goulding’s baby was dredged up on 23 April and another unidentified baby boy was discovered a week later. The total had now reached seven.

Meanwhile in Reading Prison Mrs Dyer tried to ease her mind and save her daughter and son-in-law by writing a letter to the Superintendent of Police. ‘I feel my days are numbered,’ she wrote. ‘But I do feel it is an awful thing, drawing innocent people into trouble. I do know I shall have to answer before my Maker in Heaven for the awful crimes I have committed, but as God Almighty is my Judge in Heaven as on Earth, neither my daughter, Mary Ann Palmer, nor her husband, Arthur Ernest Palmer, I do most solemnly swear that neither of them had anything at all to do with it. They never knew I contemplated doing such a wicked thing until too late.’

The matron at Reading Prison, Ellen Gibbs, said to Mrs Dyer: ‘By a letter like this, you plead guilty to everything.’ ‘I wish to,’ remarked the prisoner. ‘They cannot charge me with anything worse than I have done … Let it go.’ She never revealed how many children she had killed, merely saying later: ‘You’ll know all mine by the tape round their necks.’

The charges against Palmer and his wife were never proved, and Polly Palmer became the chief witness for the prosecution, giving evidence against her mother at the magistrate’s hearing on 2 May and later at the Old Bailey trial. Mrs Palmer’s story was that on 31 March her mother turned up in Willesden carrying a ham and a carpet bag and holding a baby, Doris Marmon, temporarily ‘for a neighbour’. The baby must have been strangled, said Mrs Palmer, while she was out fetching some coal, for when she returned the baby had disappeared and Mrs Dyer was shoving the carpet bag under the sofa. Harry Simmons, she said, must have been killed (again in Willesden) the following night, before she, her mother and her husband went out to a music hall. At any rate, he had disappeared by the following morning – Mrs Dyer had slept on a sofa in the living room – although there was an odd parcel under the sofa beside the carpet bag. ‘What will the neighbours think if they saw you come in with a baby and go away without it?’ Polly asked, allegedly. To which her mother replied, allegedly: ‘You can very well think of some excuse.’ Later that day the Palmers accompanied Mrs Dyer to Paddington Station. While Mrs Dyer went to buy some cakes to eat on the Reading train, Palmer held the now bulging carpet bag.

Mrs Amelia Dyer was charged with the murder of baby Doris Marmon and tried at the Old Bailey on 21 and 22 March 1896 before Mr Justice Hawkins. The trial began on the afternoon of the day on which Mr Justice Hawkins had sentenced to death Albert Milsom and Henry Fowler.

The Crown’s case at Mrs Dyer’s trial was put by Mr AT Lawrence and Mr Horace Avory. Mr Kapadia, who defended her, accepted that she was guilty but tried to prove that she was insane. Dr Logan of Gloucester Asylum said that in 1894 she had been violent and had suffered from delusions: she heard voices and said birds talked to her. Dr Forbes Winslow, who saw her twice in Holloway Prison, said she was suffering from delusional insanity, depression and melancholia. He did not believe she was shamming insanity. Two other doctors appearing for the prosecution said that her insanity was feigned. One of them, Dr Scott, the medical officer of Holloway, who had seen her daily, said he had discovered nothing in her that was inconsistent with her being a sane person, beyond her own statements. The jury agreed, taking a mere five minutes to find her guilty, and not insane.

Mrs Dyer, aged fifty-seven, a short, squat woman with thin white hair scraped into a bun behind her head, was hanged by James Billington at Newgate Prison on 10 June 1896. Before she died she made a long statement or confession, written in five exercise books, explaining some of her actions and thoroughly exonerating her daughter and son-in-law. When urged by the chaplain to confess, she indicated the exercise books and asked: ‘Isn’t this enough?’ Her statement ended: ‘What was done I did do myself. My only wonder is I did not murder all in the house when I have had these awful temptations on me. Poor girl [Polly], it seems such a dreadful thing to think she should suffer all this through me. I hope and trust you will believe what I say, for it is perfectly correct, and I know she herself will speak the truth, and what she says I feel sure you can believe.’

The Reading baby farmer evidently had some feelings for her own and only surviving child.