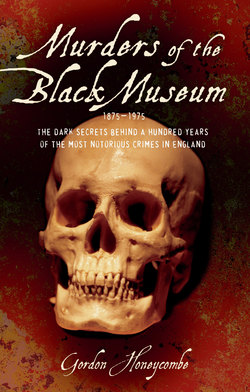

Читать книгу Murder of the Black Museum - The Dark Secrets Behind A Hundred Years of the Most Notorious Crimes in England - Gordon Honeycombe - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHARLES PEACE

ОглавлениеTHE MURDER OF ARTHUR DYSON, 1876

Murder is often compounded with theft and sex – which is to say that it frequently results from a compulsive desire to deprive, or a compulsion not to be deprived of, one’s desire. Fortunately, much thieving seems to be related to a low or inadequate sexual capability. But not always. A randy thief or robber has therefore more problems than his undersexed counterpart – problems that can lead to murder. As they did in the case of Charles Frederick Peace.

He was born in Sheffield on 14 May 1832, the son of a respected shoemaker. He was not a good scholar, but was very dexterous, making artistic shapes and objects out of bits of twisted paper. Apprenticed at a rolling mill, he was badly injured when a piece of red-hot steel rammed his leg, leaving him with a limp. He learned to play the violin with sufficient flair and skill to be billed at local concerts as ‘The Modern Paganini’. He also took part in amateur theatricals. When he was about twenty, in search of other excitements and reluctant to earn a living, he began to thieve. He was unsuccessful at first, and was jailed four times, with sentences of one month, four, six and seven years. During this period he wandered from town to town, and in 1859 met and married Mrs Hannah Ward – a widow with a son, Willie. He returned to Sheffield in 1872. Three years later, he set up shop in Darnall as a picture-framer and gilder. He was also a collector and seller of musical instruments and bric-a-brac.

In 1875, Peace was forty-three. He was, according to a police description: ‘Thin and slightly built, 5 ft 4 ins or 5 ins, grey hair … He looks ten years older. He lacks one or more fingers of his left hand, walks with his legs rather wide apart, speaks somewhat peculiarly, as though his tongue was too large for his mouth, and is a great boaster.’ He was also shrewd, cunning, selfish, salacious, ugly, agile as a monkey and very strong.

Peace became involved with his neighbours in Britannia Road, the Dysons. Very tall (6 ft 5 in) and genteel, Arthur Dyson was a civil engineer, working with railway companies. He was in America when he met his future wife, a young Irish girl called Katherine. She was tall, buxom and blooming, and fond of a drink. They married in Cleveland, Ohio. The couple often had rows. Peace – ‘If I make up my mind to a thing I am bound to have it’ – became familiar with the Dysons and enamoured of young Mrs Dyson, who unwisely responded to his attentions. It seems they visited pubs and music halls together and that their place of assignation was a garret in an empty house between their two homes. Peace took to calling on the Dysons at any time, including mealtimes. Mr Dyson put his foot down. But Mrs Dyson continued, accidentally or intentionally, to associate with Peace. In June 1876, he was forbidden to call on them any more. Arthur Dyson wrote on a visiting card, ‘Charles Peace is requested not to interfere with my family,’ and threw it into Peace’s yard.

This was something Peace could not endure. He pestered and threatened the Dysons. ‘We couldn’t get rid of him,’ said Mrs Dyson, talking later to the Sheffield Independent’s reporter. ‘I can hardly describe all that he did to annoy us after he was informed that he was not wanted at our house. He would come and stand outside the window at night and look in, leering all the while … He had a way of creeping and crawling about, and of coming upon you suddenly unawares … He wanted me to leave my husband.’

One Saturday in July 1876, Peace tripped up Mr Dyson in the street, and that evening pulled a gun on Mrs Dyson as she stood outside her house complaining to neighbours about the assault. He said: ‘I will blow your bloody brains out and your husband’s too!’ A magistrate’s warrant was obtained for his arrest and he fled with his family to Hull, where Mrs Peace ran an eating-house.

For a time the Dysons were, it appears, undisturbed. But on 26 October, they moved house, to Banner Cross Terrace in Ecclesall Road, and when they arrived (their furniture had gone ahead), Peace walked out of their front door. He said: ‘I am here to annoy you, and I will annoy you wherever you go.’

A month later, on Wednesday, 29 November 1876, Peace was seen hanging about Banner Cross Terrace between 7 and 8 pm. It was later suggested in court that Mrs Dyson and Peace had had a rendezvous in the Stag Hotel the evening before.

At eight o’clock on the 29th, Mrs Dyson put her little boy, aged five, to bed. She came downstairs, to the back parlour where her husband was reading, and about ten past eight she put on her clogs, took a lantern and, leaving the rear door open, went to the outside closet, which stood in a passage at the end of the terrace. It was a moonlit night. Peace later claimed that she left the house when he whistled for her. Her closet visit was brief. When she opened the door to emerge, Peace stood before her. ‘Speak, or I’ll fire,’ he said, presumably meaning the opposite. She shrieked, slammed the door and locked it. Mr Dyson rushed out of the rear door of the house and around the corner of the building. As he did so his wife fled from the closet. He pushed past her, pursuing Peace down the passage and on to the pavement. According to Peace, there was a struggle. He fired one shot, he said, to frighten Dyson. It missed. ‘My blood was up,’ said Peace. ‘I knew if I was captured, it would mean transportation for life. That made me determined to get off.’ A second shot was fired, striking Dyson in the head. The shots were fired in quick succession. Mr Dyson fell on to his back, and his wife screamed: ‘Murder! You villain, you have shot my husband!’ Within minutes Arthur Dyson was dead.

Peace ran off, but in doing so dropped a small packet, containing more than twenty notes and letters and Dyson’s card requesting Peace not to interfere. The notes, clearly written by a woman, included lines such as: ‘You can give me something as a keepsake if you like’ – ‘Will see you as soon as I possibly can’ – ‘You must not venture for he is watching’ – ‘Not today anyhow, he is not very well’ – ‘I will give you the wink when the coast is clear – ‘He is gone out, come now for I must have a drink’ – ‘Send me a drink. I am nearly dead’ – ‘Meet me in the Wicker, hope nothing will turn up to prevent it’ – ‘He is out now so be quick.’

From then on Charlie Peace was on the run, wanted for murder, with a reward on his head of £100. Burgling as he went from town to town and narrowly evading capture, he came in time to London, where he eventually settled in 5 East Terrace, Evelina Road, Peckham. His wife, Hannah, was installed in the basement with her son, Willie. Peace occupied the other rooms with a widowed girlfriend, Susan Grey (or Bailey), aged about thirty – ‘A dreadful woman for drink and snuff,’ said Peace. They passed themselves off as Mr and Mrs Thompson and before long she bore him a son. The house was richly furnished, adorned with a quick turnover of other people’s possessions, and alive with dogs, cats and rabbits, canaries, parrots and cockatoos. As the women were always quarrelling it must have been a very clamorous household. In the evenings, Peace sometimes entertained friends and neighbours with musical soirées, at which he played a fiddle he had made himself, recited monologues and sang.

Meanwhile, he continued his trade, driving around south London by day in his pony and trap to look for likely ‘cribs’ to crack, returning to them at night with his tools concealed in a violin case. He dressed well – ‘The police never think of suspecting anyone who wears good clothes’ – and looked quite different from his Sheffield self, having shaved off his beard, dyed his hair black and stained his face; he also wore spectacles. He became more successful, more daring than ever, and although his burglaries attracted much attention in the papers, no one knew who the culprit could be. Every Sunday he went to church with Susan Thompson.

It seems in the end that someone grassed on him, perhaps one or other of his women. Certainly the police were out in unusually large numbers in the early hours of Thursday, 10 October 1878 in the south-eastern London suburb of Blackheath.

About 2 am PC Edward Robinson noticed a flickering light in the rear rooms of 2 St John’s Park. He summoned the assistance of PC William Girling and Sergeant Charles Brown, and the latter went round to the front and rang the doorbell, while the other two hovered by the garden wall at the rear. They saw the roving light inside the house go out and a figure make a quick exit from the dining-room window on to the lawn. PC Robinson chased him across the moonlit garden, and was 6 yards away when Peace turned and shouted: ‘Keep back, keep off, or by God, I’ll shoot you!’ PC Robinson said: ‘You had better not!’

Peace fired three times, according to Robinson, narrowly missing the constable’s head. He rushed at Peace. A fourth shot missed, but as they struggled – ‘You bugger, I’ll settle you this time!’ cried Peace – a fifth shot entered Robinson’s right arm above the elbow. Undaunted, but no doubt now enraged, Robinson flung Peace on the ground, seized the revolver and hit Peace with it several times. ‘You bugger!’ said Peace, ‘I’ll give you something else!’ And he allegedly reached for some weapon in one of his pockets. But by then Girling, followed by Brown, had come to Robinson’s assistance and Peace was overpowered.

While he was being searched, Peace made another attempt to escape and was incapacitated by a blow from Girling’s truncheon. A spirit flask, a cheque book and a letter-case, stolen from the house, were found on the captive burglar, as well as a small crowbar, an auger, a jemmy, a gimlet, a centre-bit, a hand-vice and two chisels.

As Robinson was now feeling faint from loss of blood, the other two policemen took charge of Peace. He was escorted to Park Row police station near the Royal Naval College at Greenwich and not far from the River Thames. There he was charged with burglary and with the wounding of PC Robinson with intent to murder. He gave his name as ‘John Ward’, and when asked where he lived he replied: ‘Find out!’ Inspector John Bonney of Blackheath Road police station was put in charge of the case, and later that morning Peace was brought before Detective Inspector Henry Phillips, local head of the newly formed Criminal Investigation Department of Scotland Yard, the CID.

DI Phillips later wrote a full, vivid and as yet unpublished memoir of his involvement with Peace. Writing in 1899, he said that Peace’s ‘repulsive’ appearance could be verified by the wax image of him in Madame Tussauds – where it is to this day.

On the morning of 10 October 1878, Phillips and Bonney tried to elicit information from the bloody-minded burglar, who exclaimed: ‘If you want to know where I live, find out! It’s your business!’ Bonney threatened to thrash him – ‘All to no purpose,’ Phillips wrote.

Peace was then lodged in Newgate Prison, where he was visited by DI Phillips more than once. Phillips wrote later: ‘He was very talkative and boasted of his misdeeds as if they were something to be proud of.’ Phillips concluded that although Peace could seem ‘religious-minded’ and a ‘nice quiet old man’, he was really ‘a canting hypocrite’.

The following month, on 19 November 18978, Peace was tried under the name of John Ward at the Central Criminal Court in the Old Bailey, charged with the attempted murder of PC Edward Robinson. The judge was Mr Justice Hawkins; Mr Pollard was the prosecutor and Mr Montague Williams spoke on the prisoner’s behalf.

After a four-minute consultation, the jury found Peace guilty. Asked by Mr Reed, the clerk of the court, if he had anything to say before judgement was pronounced, the prisoner made a lengthy, whining, almost grovelling speech that apparently impressed most of his listeners except the judge. Peace said:

I swear before God I never had the intention to kill the policeman. All I meant was to frighten him in order that I might get away. If I had the intention to kill him I could easily have done it … I declare I did not fire five shots. I only fired four shots … I really did not know the pistol was loaded, and I hope, my lord, you will have mercy upon me. I feel that I have disgraced myself and am not fit to live or die … Give me a chance, my lord, to regain my freedom, and you shall not, with the help of God, have any cause to regret passing a merciful sentence upon me. Oh my lord, you yourself do expect mercy from the hands of your great and merciful God. Oh my lord, do have mercy upon me, a most wretched, miserable man – a man that am not fit to die. I am not fit to live; but with the help of my God, I will try to become a good man …

Peace was sentenced to penal servitude for life.

The judge then called PC Robinson forward, commended his courageous conduct, recommended him for promotion and for a reward of £25. Robinson was duly promoted to sergeant, and for many years a waxwork of him stood in Madame Tussauds beside that of Charles Peace.

The prisoner was incarcerated in Pentonville Prison, which in 1878, wrote Phillips, was ‘a preparatory prison for all convicts sentenced to Penal Servitude. It was here they performed the first nine months of their sentence, under what was known as the solitary system.’

Meanwhile, under pressure from the police, Susan Thompson had revealed the true identity of Mr Thompson, alias John Ward. She told DI Phillips: ‘He is the greatest criminal that ever lived and so you will find out. He used to live at Darnall near Sheffield and is wanted for murder and there is a reward for his arrest.’ Susan Thompson eventually claimed and received that reward – £100.

Phillips was sent north by the Director of the CID, Mr Howard Vincent, to pursue his inquiries and to find Hannah Peace (or Ward), who had returned with her son to Sheffield. It seems that Phillips had never been north of Finchley, and his experiences over the next few weeks left a lasting impression. Over twenty years later he wrote: ‘We went by the Midland Railway, all the way in the dark. The Country looked very dismal, but was lighted up by various bonfires, it being the 5th November.’ He was also very impressed by the Yorkshire police – ‘I had never got in contact with such men before. They seemed to have the Knack of making you feel you had known them for years.’

Hannah Peace (or Ward), by now aged fifty, was traced to a cottage in Darnall – ‘a wild barren-looking country, the more so in November,’ wrote Phillips. In the cottage he found a number of items which he deemed to be stolen property and arrested Hannah Peace. She appeared before the Sheffield magistrates, was remanded for a week, and some time before Christmas was taken by Phillips back to London on an overnight train. She then appeared at the Old Bailey on 14 January 1879, charged with receiving stolen goods. She was acquitted, however, on the grounds that she was Peace’s wife – although this was never actually proved – and therefore acted under his authority.

Early on the morning of Wednesday, 22 January 1879, Peace was taken, manacled and in his convict’s garb, from Pentonville Prison to Sheffield for the magistrate’s hearing into the Dyson murder. Attended by two warders, he was put on the 5.15 am express from London to Sheffield. It was very cold; up north there was snow on the ground. Peace was very troublesome during the journey, but all went well until the train neared Sheffield. It passed through Worksop and going full speed reached the Yorkshire border, where the railway line ran parallel with a canal. Phillips wrote:

Peace was well acquainted with the locality. He expressed a wish to pass water, and for that purpose the window was lowered and he faced it. He was wearing handcuffs and with a chain six inches long, so that he had some use of his hands – and he immediately sprang through the window. One of the warders caught him by the left foot. There he held him suspended, of course with the head downwards. He kicked the warder with the right foot and struggled with all his might to get free. The Chief Warder was unable to render his colleague any assistance because the Warder’s body occupied the whole of the space of the open window. He hastened to the opposite side of the Carriage and pulled the Cord to alarm the Guard, but the Cord would not act. But some gentlemen in the next compartment, seeing the state of affairs, assisted the efforts of the Chief Warder to stop the train. All this time the struggle was going on between the Warder and the Convict, and eventually Peace succeeded in kicking off his shoe and, his head striking the footboard of the Carriage, he fell on the line.

When the train eventually came to a halt, the two warders ran for over a mile back along the railway line and found their prisoner prostrate in the snow and apparently dead. To their relief he soon recovered consciousness, professing to be in great pain from a bloody wound in his head and dying of cold. A slow train heading for Sheffield chanced to appear and was stopped by the two warders. Peace was lifted up and dumped in the guard’s van at the rear. The train then proceeded on its way, arriving at Sheffield at 9.20 am. Phillips later described the scene:

An immense crowd had assembled to get sight of this great Criminal and the excitement became intense when the 8.54 Express arrived without him. The Guard reported that Peace had escaped. The crowd were unbelieving and they suggested that the statement was a ruse to get the crowd away. But when they saw a sword and a rug and a bag belonging to the Warders brought from an empty carriage and handed to Inspector Bird, it was then generally believed that the statement was true and that Peace had escaped from Custody and that the Warders were on his track. At the Sheffield Police Court great preparations had been made for the reception of Charles Peace and the Court was crowded. All the persons required to be in attendance were present, except one, and that was the Prisoner … Mr Jackson, Chief Constable of Sheffield, entered the Court in a state of some excitement and made the startling statement to the Bench that Peace had escaped from the Warders. The ordinary business of the Court proceeded, when it suddenly became known that Peace had been captured and was actually in Sheffield.

In a police station cell, Peace was examined by two surgeons. He had a severe scalp wound and concussion and vomited periodically. He complained of being cold. His wounds were dressed and he was laid on a bed in the cell and covered with rugs. ‘There the little old man lay,’ wrote Phillips, ‘with his head peeping out of the rugs, guarded by two Officers. During the first hour he was frequently roused and he partook of some brandy. At first, force had to be used to get him to take it, but subsequently he drank without any trouble. At the same time he said he should prefer whisky.’

Two days later, the surgeons certified that Peace was fit enough to attend court. In fact the court went to him, and the magistrate’s hearing was held on Friday, 24 January, by candlelight in the corridor outside his cell.

Still swathed in rugs and bandages and hunched on a chair, Peace cursed, groaned, complained and endlessly interrupted the proceedings. ‘What are we here for? What is this?’ he protested. The magistrate replied: ‘This is the preliminary enquiry which is being proceeded with after being adjourned.’ Said Peace: ‘I wish to God there was something across my shoulders! I’m very cold! It isn’t justice. Oh, dear. If I killed myself it’d be no matter. I ought to have a remand. I feel I want it, and I must have one!’

The hearing was attended by Mrs Dyson, who had been brought back to England from America, whither she had gone after her husband’s death. As the prosecution’s principal witness she seemed to enjoy the drama of her situation and was evidently not put out by Peace’s appearance and aspersions. When she took the oath without lifting her veil, Peace remarked: ‘Will you be kind enough to take your veil off? You haven’t kissed the book.’

Committed for trial at Leeds Assizes, he was taken by train to Wakefield Prison. A large crowd again assembled at Sheffield’s railway station, this time to witness his departure. Professing to be helpless, he was carried from the police van by prison warders. He looked pale and haggard, despite his brown complexion, and had a white bandage around his head. ‘He wore his Convict suit,’ wrote Phillips, ‘and very comical he looked in the cap surmounting the bandage and appeared as feeble as a Child.’

In Wakefield Prison, Peace spent the next few days writing penitential and moralising letters. One, on 26 January, was to Susan Thompson:

My dear Sue – This is a fearful affair that has befallen me, but I hope you will not foresake [sic] me, as you have been my bosom friend, and you have oftimes said you loved me, and would die for me. What I hope and trust you will do is sell the goods I left you to raise money to engage a Barrister to save me from the perjury of that villainous woman Kate Dyson … I hope you will not forget the love we have had for each other … I am very ill from the effects of the jump from the train. I tried to kill myself to save all further trouble and distress, and to be buried at Darnall. I remain your ever true lover till death.

Sue Thompson replied:

Dear Jack, I received your letter and am truly sorry to receive one from you from a Prison … I sold some of the goods before Hannah and I went away and I shared with her the money that was in the house … I had nothing to depend upon, and have not a friend of my own, but what have turned their backs upon me, my life indeed is most miserable. I am sorry you made such a rash attempt upon your life … You are doing me a great injury by saying I have been out to work with you. Do not die with such a base falsehood upon your conscience, for you know I am young and have my home and character to redeem. I pity you and myself to think we should have met … Yours, etc – Sue.

On Tuesday, 4 February 1879, Charles Peace was put on trial at Leeds Assizes before Mr Justice Lopes; the prosecutor was Mr Campbell Foster, QC, and the accused was defended by Mr Frank Lockwood. The court was packed, many of the women being armed with opera glasses. Peace, wizened and unshaven, his scarred head and hollow features bristling with thin grey hairs, sat in an armchair within a spiked enclosure.

The prosecution’s chief witness, Mrs Dyson, although evidently embarrassed by the implications of some of the prosecution’s more personal questions, behaved with a degree of indecorum, even levity. When asked by Campbell Foster how wide the passage was outside the closet she replied: ‘I don’t know, I am not an architect.’ To the question: ‘Did anything touch your husband before he fell on his back?’ she replied: ‘The bullet touched him.’ ‘I didn’t ask that,’ scolded Campbell Foster. ‘Did Peace touch him with his foot?’ She retorted: ‘No, but the bullet touched him.’ There was laughter in court. Campbell Foster was more successful in implying that Mrs Dyson had had an association with Peace, that he gave her a ring, that she continued to meet him after her husband had expressed his dislike of Peace, and had been photographed with him at the Sheffield Summer Fair in 1876. She denied that letters and notes referring to assignations were in her handwriting. But she was forced to admit when confronted by witnesses, that she had gone with Peace to some pubs and music halls. However, she denied that she had ever been evicted from a pub for being drunk, and that she was with Peace in the Stag Hotel the night before her husband was killed.

Various witnesses corroborated the circumstances surrounding the shooting of Arthur Dyson. Mr Lockwood, defending, proposed that the shooting was accidental, that Peace’s threats were meaningless, and that the prosecution’s principal witness was unreliable and her evidence tainted and uncorroborated. The judge told the jury that the plea of provocation failed altogether ‘where preconceived ill-will against the deceased was proved’.

The jury took fifteen minutes to reach a verdict of ‘guilty of wilful murder’, and Peace was sentenced to death. On being asked if he had anything to say, he murmured: ‘Will it be any use for me to say anything?’

Peace was removed to Armley Jail in Leeds where, in penitential mood, he made a full confession of all his crimes to the Reverend JH Littlewood, vicar of Darnall. In it, he revealed that he had shot another policeman – and killed him – in Manchester on 1 August 1876, four months before the death of Arthur Dyson.

Peace’s story was that PC Nicholas Cock and another constable had disturbed him when he was about to burgle a group of prosperous houses called Whalley Range. PC Cock surprised Peace as he climbed over a wall and shouted at him to stand where he was. ‘This policeman was as determined a man as myself,’ said Peace, ‘and after I had fired wide at him, I observed him seize his staff, which was in his pocket, and he was rushing at me and about to strike me. I then fired the second time. “Ah, you bugger,” he said, and fell. I could not take as careful an aim as I would have done, and the ball, missing the arm, struck him in the breast. I got away, which was all I wanted.’

Two young Irish brothers called Habron, farm labourers, were accused of the crime at Manchester Assizes and one of them, William Habron, aged nineteen, was sentenced to death on 28 November 1876 – the day before the murder of Arthur Dyson. William’s brother, John was found not guilty, and the jury added a recommendation for mercy to William Habron ‘on the grounds of his youth’. For three weeks he was confined in a condemned cell. But on 19 December the Home Secretary granted a reprieve and William’s sentence was commuted to one of penal servitude for life. He was sent to Portland Prison, where he remained for over two years.

Peace had watched the Habron trial from the public gallery and kept silent. He said later: ‘What man would have done otherwise in my position?’ But now that he was to be executed himself, he told the Reverend Littlewood that he thought it right ‘in the sight of God and man to clear the young man’. He ended his confession by saying: ‘What I have said is nothing but the truth and this is my dying words. I have done my duty and leave the rest to you.’

Charles Peace was hanged by William Marwood at Armley Jail in Leeds at 8 am on 25 February 1879.

His last days were spent in interminable letter-writing and prayer and the Christian exhortation of others. But his reprobate real self prevailed. Of his last breakfast he said: ‘This is bloody rotten bacon!’ And when a warder began banging on the door as Peace lingered overlong in the lavatory on the morning of his execution, he shouted: ‘You’re in a hell of a hurry! Are you going to be hanged or am I?’ On the scaffold he refused to wear the white hood – ‘Don’t! I want to look’ – and insisted on making a speech of forgiveness, repentance and trust in the Lord. Four journalists who were present wrote down his last words, spoken as his resolution left him: ‘I should like a drink. Have you a drink to give me?’ As he spoke, Marwood, the executioner, released the trap door. Peace fell; the vertebrae at the base of his head fractured and dislocated, and his spinal cord was severed.

He wrote his own epitaph for the memorial card which he himself had printed in jail: ‘In memory of Charles Peace who was executed in Armley Prison, Tuesday, February 25th 1879. For that I done but never intended.’

On 19 March, William Habron was moved from Portland to Millbank Prison in London and then set free with a full pardon. He was told that his father had died six months earlier ‘of a broken heart’. He was given £1,000 in compensation ‘to ease his pain and anguish’.

In due course, DI Henry Phillips donated some items that had been used by Peace in his burglaries to the Black Museum at Scotland Yard. A hundred years later, Phillips’s very informative, hand-written memoir was in turn donated to the museum by lorry driver Peter Coyle, on behalf of Phillips’s great-niece, Mrs Bell.