Читать книгу Cary Grant: A Class Apart - Graham McCann - Страница 14

CHAPTER V Inventing Cary Grant

ОглавлениеYes, despite his appearance, he was really a very complicated youngman with a whole set of personalities, one inside the other like a nest ofChinese boxes.

NATHANAEL WEST

I guess to a certain extent I did eventually become the characters I wasplaying. I played at being someone I wanted to be until I became thatperson. Or he became me.

CARY GRANT

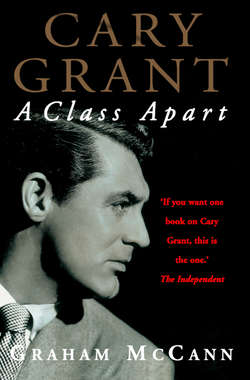

If Archie Leach, as he left New York for Hollywood, had come to think of himself as a self-made man, then Cary Grant, as he stepped out into the Southern Californian sunlight, would come to think of himself as a man-made self. Archie Leach had learned a great deal in a short period about how to perform, but, so far, he had learned little about how best he might use this technical knowledge to lend a certain distinctiveness to his own performances. Cary Grant would bring an unusual, attractive, imaginative personality to complement the existing solid technique. The change of name, in itself, was banal; it was common practice in Hollywood, where words were put to the service of pictures and one’s name functioned as a sub-title for one’s image. The change of identity, however, was profound; the new name heralded a new self.

Archie Leach did not arrive in Los Angeles with any great expectation of such a rapid and dramatic transformation. He was hopeful of employment in Hollywood, but he was not desperate; he knew that the Shuberts were eager to use him again, should he wish, or need, to return to Broadway. He could afford, therefore, to approach this new challenge with enthusiasm rather than trepidation.

There are, perhaps predictably, several versions of how Archie Leach managed to secure for himself a studio contract. One account, which was popularised by Mae West, has it that she ‘discovered’ him when he was a humble extra on the Paramount lot.1 This is quite untrue; indeed, it was a canard that continued to infuriate Cary Grant whenever he saw it in print.2 He was never an extra, and he had made seven movies before he first appeared with Mae West. Another version – more plausible but still with no documented evidence to support it – was put forward by Phil Charig: according to his account, he took Archie Leach with him when he was summoned for an interview at Paramount’s music department, and, although he was not offered a job, the interviewer was sufficiently impressed by Leach’s good looks to recommend him for a screen test.3 There is, however, another version which, since it originated with Grant himself and there is no obvious reason to doubt him on this matter, may be regarded as authoritative: according to Grant, a New York agent – Billy ‘Square Deal’ Grady of the William Morris Agency – gave him the office address in Hollywood of his friend Walter Herzbrun, and Herzbrun, in turn, introduced him to one of his most important clients, the director Marion Gering.4

Archie Leach did not just have handsome features – plenty of other young, out-of-work actors in Los Angeles at that time were that good looking – he also had genuine charm. It is clear that Archie Leach found it remarkably easy to find people who were able and willing to support his embryonic career. As had happened in New York, Leach became a popular new guest at Hollywood social occasions, and it was not long before he had the opportunity to impress a number of producers and directors. His new, unofficial patron Marion Gering was planning to screen-test his wife, and he thought that Leach could play opposite her. Gering took Leach to a small dinner party at the home of B. P. Schulberg, the head of production at Paramount’s West Coast studio. Schulberg was, it seems, happy to accede to Gering’s request, and a screen test and the offer of a long-term contract (worth $450 per week) were the results.

Archie Leach had achieved, with what seems like remarkable ease, the basis for a movie career. Before he could begin acting in any movies, however, he first needed to work on his identity. As with many young contract players, the studio questioned the marquee value of his name: ‘They said: “Archie just doesn’t sound right in America.’” ‘It doesn’t sound particularly right in Britain either,’ was his rather embarrassed reply.5 He was told, without any intimation that the matter might be open to negotiation, that ‘Archie Leach’ was unacceptable, and was instructed to come up with a new name ‘as soon as possible’.6 That evening, over dinner with Fay Wray and John Monk Saunders (the author of Nikki), it was suggested that Leach might adopt the name of the character he had played in their show: Cary Lockwood. Leach liked ‘Cary’ as his first name, but he was told by someone at the studio that there was already a Harold Lockwood in Hollywood,7 and so the search for a new surname continued.8 The studio advised him to choose a short name: it was the era of Gable, Cooper, Cagney and Bogart. A secretary gave Leach the standard list of suggestions which had been compiled for such a purpose. ‘Grant’, according to his own recollection of the deliberations, was the surname which ‘jumped out at me’.9

Paramount, it seems, was equally satisfied with the combination. ‘Cary’ sounded pleasingly ambiguous, a supple name which, when pronounced to rhyme with ‘wary’, could suit a sophisticated image, and, when pronounced to rhyme with ‘Cary’, could fit with a more plebeian persona. The name’s new owner never seemed particularly interested in proposing a definitive pronunciation: some of his friends, such as Alfred Hitchcock, favoured the former, while others, such as David Niven, favoured the latter (he himself managed, typically, to find a subtle via media, and he only ever protested when anyone attempted to call him ‘Car’). ‘Grant’, on the other hand, sounded reassuringly American; it had more simple and solid connotations, a nod perhaps to the Hero of Appomattox, General Ulysses S. Grant, eighteenth president of the United States. Someone noticed that Cary Grant’s initials were the same as Clark Gable’s and the reverse of Gary Cooper’s; it seemed a good omen – Gable and Cooper were the most popular matinee idols of the day.

Cary Grant was born, in effect, on 7 December 1931,10 the day that he signed his Paramount contract and consigned ‘Archie Leach’ to relative – but by no means complete – obscurity at the age of twenty-seven years and eleven months. Cary Grant was not a new man, but rather a young one with the rare opportunity to restyle himself in a manner which would suit his aspirations. The name change itself was a fairly routine, pragmatic decision by the studio; it was not intended as an invitation to Archie Leach to embark on any profound voyage of self-discovery. Paramount had already decided who Cary Grant should be: a cut-price, younger, dark-haired substitute for Gary Cooper.11 Cooper had joined Paramount in 1927; by 1931, he was complaining that he was being worked too hard. While he was filming City Streets that year, he suffered a near collapse from the combined effects of jaundice and exhaustion. When the movie had been completed, he left for Europe, and began to spend more time with the Countess Dorothy di Frasso than his studio felt was desirable. Archie Leach, smoothed out into the more refulgent form of ‘Cary Grant’, was to be used to remind Cooper – gently at first – that he was not quite as distinctive nor as valuable as he might have thought he was. The two men did have a number of things in common: both had English backgrounds (Cooper’s parents were both English, and he had been educated in Bedfordshire12); both were physically powerful men who could also show their vulnerability; and both were versatile enough to play comic as well as romantic roles.

Cary Grant, it was reasoned, could be groomed for stardom by taking the ‘Gary Cooper roles’ that Gary Cooper turned down, and, by playing on the perceived similarity between the two men, Paramount hoped that Cooper’s ego could be held in check by the constant presence of a possible replacement at the studio. A fan magazine of the time – possibly with some covert encouragement from Paramount’s publicists – noted that ‘Cary looks enough like Gary to be his brother. Both are tall, they weigh about the same, and they fit the same sort of roles.’13 Cooper had been warned. It was a common tactic employed by all studios at the time to prevent their most popular stars from becoming too ‘difficult’: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, for example, had brought in James Craig as a threat to Clark Gable, and Robert Young as a threat to Robert Montgomery. It was good insurance. If Gary became too demanding, Cary could take over (only a modest dash would need to be erased on the dressing-room door); it was considered unlikely, and, as often happened in similar cases elsewhere, it was probably thought more likely that Cary Grant would become a useful romantic lead in a string of relatively modest movies.

Cary Grant, however, had a quite different outlook on the possibilities opened up by his sudden change of identity. He did not wish to live indefinitely within quotation marks; he wanted to create a ‘Cary Grant’ that he could grow into. Whoever this ‘Cary Grant’ was to be, he would have to be someone who seemed real to Archie Leach as well as to others: ‘If I couldn’t clearly see out, how could anyone see in?’14 All that he started with, he admitted, was a façade, and ‘the protection of that façade proved both an advantage and a disadvantage’.15 It offered him both the chance to change and an excuse not to change. Archie Leach wanted to change. The playwright Moss Hart remembers him back in his New York days, mixing with a group of ‘have nots’ at Rudley’s Restaurant on 41st Street and Broadway. According to Hart, Archie Leach had appeared to be ‘a disconsolate young actor’ whose ‘gloom was forever dissipated when he changed his name to Cary Grant’.16

Archie Leach saw his reincarnation as ‘Cary Grant’ not as the end of his self-reinvention but rather as the start of it. The writer Sidney Sheldon, who came to know and work with Grant in the forties, used him as the prototype for Rhys Williams, a character in the novel Bloodline; Williams is described as ‘an uneducated, ignorant boy with no background, no breeding, no past, no future’, but, with ‘imagination, intelligence and a fiery ambition’, he transforms himself from ‘the clumsy, grubby little boy with a funny accent’ into a ‘polished and suave and successful’ man.17 Archie Leach was eager to learn, to absorb as much as he could from the places and people he encountered. His lack of formal education remained one of his lifelong regrets.18 Since his arrival in the US, he had made a point of making the acquaintance of people who were gifted and highly educated. Rather like the character in Bloodline, he ‘was like a sponge, erasing the past, soaking up the future’.19 He was not ashamed of his working-class background, but he did want to take every opportunity to pursue the project of self-improvement; he was, in part, eager to educate himself, but also he was reacting, with bitterness, to the memory of the routine humiliations suffered by himself, his family and his friends back in England. He studied other people’s dress sense, table manners, gestures and accents. He was not going to be ‘caught out’. The composer Quincy Jones, who formed a friendship with him in later years, remarked that when he was growing up, ‘the upper-class English viewed the lower classes like black people. Cary and I both had an identification with the underdog. My perception is that we could be really open with each other because there was a serious parallel in our experience.’20 John Forsythe, who acted alongside him in the forties, made a similar point: Archie Leach had been ‘a poor kid. He did scrape his way to the top. That meticulous quality he had – knowing how to best use himself – was one of the key things to his nature.’21

The idea of America – its promise of liberty and equality – inspired Archie Leach, as it had inspired many other English people from similar backgrounds. Betsy Drake, who became Cary Grant’s third wife, recalled that ‘in Cary’s day you got nowhere – nowhere – with a lower-class accent. The fact that he survived all that speaks very well for him.’22 Though America had its own casual snobberies, it was, none the less, considerably more democratic in outlook and disposition than the England that Archie Leach had grown up in. Categories in England were particularly rigid then, and social distinctions emphatically made and scrupulously preserved. In America, on the other hand, Archie Leach could, to some extent, avoid such potential disadvantages. Only an expert in contemporary English class distinctions could have contemplated slotting him firmly into a particular niche; to most people he was just a good-looking and personable young man.

Archie Leach had some sense of what kind of person he wanted Cary Grant to be. Glamorous, for instance. Archie Leach wanted Cary Grant to be the epitome of masculine glamour. To this end his first chosen role-model was Douglas Fairbanks. He had met Fairbanks before he even set foot in America. Fairbanks and his wife, Mary Pickford, had been passengers on the RMS Olympic on the same voyage to the US as Archie Leach and the rest of the Pender troupe. The couple were returning to America after their much-publicised six-week honeymoon in Europe. Fairbanks fascinated Archie Leach. Tall, dark and handsome, an international screen idol, a ‘self-made man’ (with just a little help from Harvard), a fine athlete and, as his young admirer noted, ‘a gentleman in the true sense of the word. A gentle man. Only a strong man can be gentle.’23 Archie Leach was thoroughly impressed by Fairbanks, off screen as well as on; Fairbanks symbolised the kind of man – and star – that the then still somewhat gauche teenage Archie Leach wanted one day to become. What is more, Archie knew enough of Fairbanks’s biography, gleaned from movie magazines and newsreels, to see that they had much in common: disrupted and largely unhappy childhoods, alcoholic fathers, acrobatic training, apparently limitless high spirits and a capacity to enjoy their own good luck. Fairbanks had triumphed; he had achieved fame, wealth and power, as well as marrying ‘America’s sweetheart’.24 ‘For a man coming out of darkness into light,’ commented the critic Richard Schickel, ‘there was, possibly, a promise in Fairbanks.’25

At one point, late on during the crossing, Archie Leach found himself (probably less fortuitously than he later liked to suggest) being photographed alongside his hero during a game of shuffleboard: ‘As I stood beside him, I tried with shy, inadequate words to tell him of my adulation. He was a splendidly trained athlete and acrobat, affable and warmed by success and well-being.’26 Archie’s glimpses of Fairbanks on that first Atlantic crossing provided him with his initial, and possibly most enduring, image of modern elegance and style. Cary Grant always attributed his almost obsessive maintenance of a perpetual suntan to that first sighting of Fairbanks’s deeply bronzed complexion,27 and he was also equally impressed by the relatively thoughtful and understated elegance of Fairbanks’s dress sense (he was not the only one: many of the studio bosses had started out in the clothing trade, and there were few sights more likely to have them purring with delight than that of a well-tailored suit28). An Anglophile, Fairbanks had his suits made in Savile Row by Anderson & Sheppard, his evening clothes by Hawes & Curtis, his shirts by Beale & Inman and his monogrammed velvet slippers by Peel. Grant never forgot the subtle precision of that celebrated sartorial flair. Ralph Lauren has said that, years later, Grant described, in minute detail, how Fairbanks looked, and he urged Lauren to make a double-breasted tuxedo ‘like the one worn by Fairbanks, same lapel and all’.29

Archie Leach was aware, however, that he could not, and should not, simply replicate the Fairbanks look. Cary Grant could not be another Fairbanks. Fairbanks was, at least on the screen, an all-American hero and Cary Grant, whatever, whoever, he might become, was never going to pass for an all-American hero. Gary Cooper would be able to grow into the role of the westerner, his voluptuous, gentle-looking face changing gradually – as though it had long been left thoughtlessly outside at the mercy of the elements – into a harder, rougher complexion, but Cary Grant could not go far in that particular direction. If Cary Grant’s future was American, his lineage was English. He could change the way he looked rather more effectively, and speedily, than he could change the way he sounded. His accent, when he arrived in Hollywood, was the oddest thing about him. Nobody talked like that, not even Archie Leach in earlier years.

There is no reason to believe that Archie Leach, during his childhood and early adolescence, sounded in any way different from other working-class Bristolians. There are, indeed, some who claim to be able to discern the distinctive ‘burr’ of his old Bristol accent beneath the assumed American tones.30 It seems likely that Archie Leach’s accent first began to change during the period he spent in London with the Pender troupe. It was not just that he was, at the impressionable age of fourteen, exposed to the distinctive dialects associated with South London, but also, more specifically, that he was drawn into the London music-hall community, which had developed its own semiprivate patois, something described by one performer as ‘a mixture of Cockney, Romany and Hindustani’.31 Archie Leach, in time, would speak in his own odd hybrid of West Country and mock-cockney, with an increasingly distinctive staccato enunciation. Ernest Kingdon, his cousin, believed that this peculiar accent was to some extent the result of the fact that he was ‘trying to maintain English speech, and he had trouble with his diction … It’s not cultured English talk [but] very precise … as if he’d been taught elocution.’32 This very individualistic way of speaking was probably made even more noticeable during the years Leach spent touring the music-halls in Britain and America with the Penders. Peter Honri, a member of one of Britain’s most famous music-hall families, has noted that the so-called ‘music-hall voice’ relied not so much on volume as on ‘pitch and resonance’ – it was ‘a voice with a cutting edge’.33

Archie Leach, as he struggled to survive in New York, realised that being – or, more pointedly, sounding – English limited the number of stage roles he could, with any seriousness, audition for.34 ‘I still spoke English English, and I knew that to get jobs here, I’d have to learn American English.’35 He was not trying consciously to erase the sounds that associated him with a certain geographic and class background; he was simply trying to make himself more employable in his new environment. As Richard Schickel has argued, he was probably aiming not for affectation but rather for ‘something unplaceable, even perhaps untraceable’, a malleable accent that could lend a ‘democratic touch of common humanity’ to an aristocratic role and a ‘touch of good breeding’ to the more raffish parts.36

He did his best, and, of course, his accent had already begun to change during those first formative years he had spent in the United States,37 but the transformation process was both slow and incomplete. Some New Yorkers during this time mistook him for an Australian,38 and a number of his colleagues, for a brief period, took to calling him ‘Boomerang’, ‘Digger’ or ‘Kangaroo’ Leach (years later, in Mr Lucky, he referred back to this strange misconception, having his character explain his use of cockney rhyming slang by saying, ‘Oh, it’s a language I picked up in Australia’). Although his accent, once he had settled in Hollywood, grew gradually into its now-familiar transatlantic timbre, it continued to strike some American admirers as beguilingly exotic. The critic Richard Corliss, for example, writing on the occasion of Cary Grant’s death, recalled the ‘cutting tenor voice that refused to shake its Liverpool origins’39 (which is rather like suggesting that James Stewart never quite managed to lose his Texan twang). Grant himself remained appealingly unpretentious and self-effacing when referring to his accent: when Jack Warner offered him Rex Harrison’s role in the movie version of My Fair Lady, he exclaimed, ‘I cannot play a dialectician – a perfect English teacher. It wouldn’t be believable … I sound the way ’Liza does at the beginning of the film.’40

If the accent was, and would continue to be, unique, it was distinctive in the ‘right’ kind of way as far as Hollywood producers were concerned. There was a demand at the time for British (or at least British-sounding) actors, because the diction of so many American performers was, it was thought, ill-suited to the technical limitations of the early ‘talkies’. Although Archie Leach had arrived in Hollywood with his accent a volatile mixture of West Country, South London and New York, Cary Grant was able to attract attention by the way he sounded as well as by the way he looked. That accent, as a critic, Alexander Walker, has pointed out, gave the new personality an ‘edge’; it impressed on the voice ‘the sharpness that comedy needs if it’s to be slightly menacing’.41 It would, in time, become the kind of accent that could underline the humour in well-written dialogue and disguise the absence of it in the most mediocre of lines. Writers, as a consequence, were among Cary Grant’s most genuine admirers. Listen to the way, in The Awful Truth (1937), that Grant, serving a rival with a glass of egg-nog, manages to make the innocent question, ‘A little nutmeg?’ sound like a threat, or how, in The Grass is Greener (1960), he places such an artfully sardonic emphasis on the question, ‘Do you like Dundee cake?’, that it succeeds in mocking both the place-name and the antiquated mannerisms of his upper-class character. Cary Grant would become the kind of person who, as David Thomson put it, ‘could handle quick, complex, witty dialogue in the way of someone who enjoyed language as much as Cole Porter or Dorothy Parker’, with a memorably serviceable accent, caught between English and American, working-class and upper-class, that produced a tone that could be made to sound ‘uncertain whether to stay cool or let nerviness show’.42

If Cary Grant was going to be someone who sounded unorthodox, he was also, in rather less obvious but equally significant ways, going to be someone who looked unorthodox. Whereas most other actors in Hollywood at that time were known either for their physical or verbal skills, Archie Leach, unusually, possessed both. Silent screen comedy had demanded performers who could be as funny as possible physically, noted the critic James Agee, ‘without the help or hindrance of words’. The screen comedian, before sound took hold of Hollywood, ‘combined several of the more difficult accomplishments of the acrobat, the dancer, the clown and the mime’.43 The advent of the ‘talkies’ marked a change in direction. Archie Leach, with his vocal mannerisms and his acrobatic training, had the rare opportunity to make Cary Grant an appealing hybrid: a talented physical performer with a rare gift for speaking dialogue, someone who could, whilst remaining in character, utter a string of sophisticated witticisms before slipping suddenly on a solitary stuffed olive and landing ignominiously on his backside. One movie historian commented on what it was like to grow up in the 1920s with but one wish: to be ‘as lithe as Fairbanks and as suavely persuasive as Ronald Colman’.44 Cary Grant had the rare chance to realise such a wish.

Archie Leach did not take long to see that the opportunity existed, and Cary Grant exploited it. He brought athleticism to elegance, physical humour to the drawing-room. It was the kind of unexpected versatility which undermined the rigid screen stereotypes, and it would help Cary Grant to become ‘an idol for all social classes’.45 As Kael explains, other leading men, such as Melvyn Douglas, Henry Fonda and Robert Young, could produce proficient performances in screwball comedies and farcical situations, ‘but the roles didn’t release anything in their own natures – didn’t liberate and complete them, the way farce completed Grant’.46 It was as though the grace of Fred Astaire had combined with the earthiness of Gene Kelly. David Thomson observed: ‘Only Fred Astaire ever moved as well as Cary Grant, but Grant moved with more dramatic eloquence while Astaire cherished the purity of movement. Grant could look as elegant as Astaire, but he could manage to look clumsy without actually sacrificing balance or style.’47

Cary Grant’s potential could not be realised, however, until Archie Leach found the confidence to start acting like Cary Grant, and to start he needed first to develop a reasonably sharp sense of who Cary Grant should act like. Cary Grant, Archie Leach decided, should act like those stars who, up until then, had most impressed him. By his own admission, Cary Grant was in part, at the beginning, patterned on a combination of elegant contemporary Englishmen:

In the late 1920s I’d wavered between imitating two older English actors, of the natural, relaxed school, Sir Gerald DuMaurier and A. E. Matthews, and was seriously considering being Jack Buchanan and Ronald Squire as well; but Noël Coward’s performance in Private Lives narrowed the field, and many a musical-comedy road company was afflicted with my breezy new gestures and puzzling accent.48

Coward’s unapologetically reinvented self – and accent – was of particular relevance. Alexander Walker comments how Coward’s example – above all others – probably encouraged Archie Leach ‘to abandon the stigmata of English class’.49 Archie Leach had admired another British playwright, Freddie Lonsdale, because he ‘always had an engaging answer for everything’,50 but Coward’s supremely confident manner and sparkling wit, as well as his success on both sides of the Atlantic (The Vortex had broken box-office records on Broadway), were particularly influential. Leach’s imitation, fixed as it was on the surface aspects of self, was graceless at first, but he learned from its limitations: ‘I cultivated raising one eyebrow, and tried to imitate those who put their hands in their pockets with a certain amount of ease and nonchalance. But at times, when I put my hand in my trouser pocket with what I imagined was great elegance, I couldn’t get the blinking thing out again because it dripped from nervous perspiration!’51

In addition to the English role-models, Archie Leach also looked to those examples he had noted of American charm and elegance. Fairbanks was, of course, an important influence, but so too were Fred Astaire and the man described by Philip Larkin as ‘all that ever went with evening dress’,52 Cole Porter (whom Cary Grant later portrayed – much to his discomfort and Porter’s delight – in the 1946 musical Night and Day). Another significant figure for Archie Leach was the actor Warner Baxter, described by one journalist at the time as ‘a Valentino without a horse’,53 the ‘beau ideal’ who had been the first screen incarnation of Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1926) as well as the leading man in the first version of The Awful Truth (1925) – the re-make of which confirmed Cary Grant as a star.

A Hollywood star persona was cultivated, typically, through a combination of performance – carefully-chosen screen roles – and publicity – studio press releases and magazine stories.54 Cary Grant emerged at a time when audiences had started reading rather more than before about the performers they saw on the screen; the fan magazine detailed every aspect of the stars’ lives, real and imaginary, and they sold by the million:

The success of the fan magazine phenomenon of the 1930s was a co-operative venture between the myth makers and an army of readers willing to be mythified. The magazines rewarded their true believers with a Parnassus of celluloid deities who climbed out of an instant seashell like Botticelli’s Aphrodite.55

Motion picture magazines soon began referring to Paramount’s ‘suave, distinguished’ Cary Grant, a new star-in-the-making for whom, it was said, ‘the word “polished” fits … as closely as one of his own well-fitting gloves’.56 He was, readers were told, a ‘handsome’ and ‘virile’ young man who ‘blushed “fiery red” when embarrassed’, and, it was added, he had the ‘same dreamy, flashy eyes as Valentino’.57 While his studio worked hard to find the right kind of publicity to promote its own version of ‘Cary Grant’, he was advised, in the short term, to say little of any consequence himself. However, the studio soon realised that Grant was actually being rather too reticent for his own good. A Paramount publicist at the time came to regard the task of securing coverage for the relatively unknown Cary Grant as probably the most difficult and frustrating experience of her whole career as a press agent.58 Having grown up with very few close personal ties, he had developed the habit of keeping his thoughts and beliefs to himself, and, having recently transformed his public self, he was over-cautious when subjected to journalistic requests for all the ‘facts’ about Cary Grant rather than Archie Leach. As one reporter noted after a very early encounter with him, ‘Anything he says about himself is so offhand and perfunctory that from his own testimony you get only the sketchiest impression of him.’59 A writer on Motion Picture magazine was similarly frustrated: ‘Seldom have I seen a man so little inclined to pour out his soul, and you have to scratch around and dig in order to discover even the bare facts of his life from him.’60

Paramount could package Cary Grant but it could not control entirely how he impressed himself on a movie audience. If Cary Grant was in danger of resembling a tabula rasa in the journalistic profile, on the movie screen he would soon seem, as Katharine Hepburn put it, ‘a personality functioning’.61 On the screen Cary Grant could be himself rather than explain himself (and that alone, in a sense, provided one with an adequate explanation). The actor Louis Jourdan has spoken of the impact that Cary Grant’s early movie performances had on him: ‘I was in awe of this persona, the look, the walk … The Cary Grant I fell in love with on the screen hadn’t yet discovered he was Cary Grant.’62 This new, unfamiliar, intriguing character called ‘Cary Grant’ was, as Jourdan appreciated, someone who did not fit neatly into the stereotypical roles but who was, on the contrary, a character in conflict with himself:

Behind the construction of his character is his working-class background. That’s what makes him interesting. That’s what makes him liked by the public. He’s close to them. He’s not an aristocrat. He’s not a bourgeois. He’s a man of his people. He is a man of the street pretending to be Cary Grant!63

It was one of the most admirable achievements of Cary Grant: that he never had, or wished, to renounce his past in order to embrace his future. Unlike those stars who seemed ashamed of, or embarrassed by, their humble origins, Cary Grant seemed content to stand upon his singularity; it would, for example, have taken a reckless person to risk calling Rex Harrison ‘Reg’ to his face, but Cary Grant delighted in slipping references to his former name into his movie dialogue – such as the ad-libbed line in His Girl Friday (1940): ‘Listen, the last man who said that to me was Archie Leach just a week before he cut his throat.’64 It was a knowing wink to the audience, his audience, a secret shared with strangers; it was the kind of gesture that would have endeared someone like Cary Grant to someone like Archie Leach.

Archie Leach did not cease to exist when Cary Grant was created. ‘Cary Grant’ was just a name, a cluster of idealised qualities. Cary Grant became something other than the sum of his influences, and he preserved more than it might have appeared from his own personal history in that charismatic conformation. Cary Grant was not conceived of as the contradiction of Archie Leach, but rather as the constitution of his desires. If Cary Grant succeeded, Archie Leach, more than anyone else, more than any other influence or ingredient, would be responsible. Cary Grant would always appreciate that fact. Fifty years after he changed his name, when he was the subject of a special tribute,65 he requested that the cover of the programme for the occasion should feature a photograph of himself at the age of five – signed by ‘Archie Leach’.