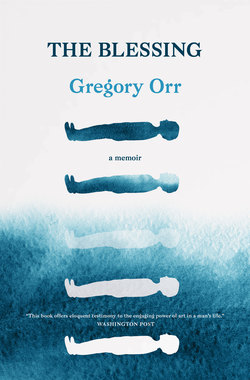

Читать книгу The Blessing - Gregory Orr - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

Guns

There was a ridge above the field. It had been cut clear of trees when a power line went through the year before and now its shrub-grown flank sloped down sharply into the flat grassy field below. It was land we owned, part of the hundred acres of woods and fields that went with the old house my parents had bought two years back. It was Saturday, and we were digging a trench there, with shovels and a pick—my older brother, Bill, and me. It had the rough shape of something sextons might dig in a cemetery, but not nearly so deep. I was a skinny kid and tired easily. Whenever I stopped to catch my breath, I tried to adopt what seemed to me an adult’s pose, resting my chin on my gloved hands folded over the top of the shovel handle and gazing casually out over the field as if there were something there to see, while my heart thumped against the wood handle and my open-mouthed panting made little, spasmodic breath-clouds that held briefly in the still November air.

Late that afternoon, back from his house calls and not yet due for evening hours in the office at the back of our house, Dad trudged up the hill to survey our progress. What he thought meant everything to us, and though it was a job anyone could do, we worried that somehow the trench we’d dug wasn’t good enough. When he climbed down in it, the top hardly came above his shins, and it was too narrow for him to squat without banging his knees. “You’ll have to do better than that,” he said, brushing the dirt from his khaki pants.

Monday would be the first day of deer season. Long before dawn, we three would be crouched there in that same dank trench, each of us holding his own rifle. Bill was fourteen and had a .222; I was twelve and had been given a lightweight .22 for my eleventh birthday. Dad had a 30.06 whose telescopic scope and leather shoulder sling made it seem both more real and more magical than our own guns. It was a vision of ourselves as heroic hunters that kept us digging that weekend, despite the blisters forming under our gloves and the sweat trickling down our ribs as we labored to heave the dirt out of the deepening hole. Jonathan and Peter stood around and watched as Bill and I dug, but they weren’t part of the story. Only ten and eight, they were still kids. Their job was to envy us, who, even with this mundane-seeming task of digging with pick and shovel, had actually already begun an initiation that would set us apart from them, would place a huge, longed-for gulf between our childhoods and our future. This would be our first deer-hunting season; this, we sensed, would be a crucial passage into manhood for us both.

I’d been hunting for what seemed a long time before that day. I was given my first gun, a .410-gauge shotgun, by my father when I was ten. My .22 rifle had a pump action and could hold eight rounds, and was fashioned from a new alloy that made it so light it almost seemed toylike.

On a typical spring day of that year, when the four of us got off the school bus, we’d go our own ways. Bill would close himself in his room and listen to records or pop music on his radio. Jon and Peter would wander off to play together or maybe watch TV. Mom was usually busy with Nancy, who was only four. I’d change out of my school clothes and, while still in my stockinged feet, slip into the library where all three rifles were kept on a pale pine gun rack. (My father’s loaded pistol was in his office desk drawer in the next room.) The library was a dark room, three walls floor to ceiling with bookshelves; the fourth had a green floral couch with the gun rack mounted above it. As I balanced unsteadily on the couch cushions and reached up for my rifle, the pine supports were like open white hands emerging from the wall to offer it to me. The ammunition boxes were in a small, unlocked drawer at the base of the rack. I’d slip a box of bullets into my windbreaker pocket, put on my sneakers, and be out the door in minutes, headed for the woods that bordered our yard on two sides. I’d roam the woods for hours, until dusk or cold forced me home. These excursions were motivated half by a passion for wandering in the woods, half by a desperate loneliness that weighed me down. When I was in the woods, I felt free and released from a vague misery I didn’t understand. My dream of being in the woods involved absolute silence, and every footfall that crackled leaves or snapped twigs bothered me. I wasn’t happy until I found a fallen log where I could sit for a long time without moving or making a sound. I wanted to be so still I would become invisible, so that the woods would return to the state they’d been in before I arrived and the animals would move about as if I weren’t even there. I wanted to sit so still and breathe so softly that I became only a pair of eyes gazing out into the woods, alert to the fall of a leaf or the distant call of a jay. That much of my dream was benign—the fantasy of my body becoming transparent or vanishing entirely, to be replaced by nothing but focused wonder and the will to observe. It was a desire and pleasure I’d felt for years growing up in the country, miles from the nearest village. But now I carried a gun and that weapon aroused a counter-spirit from somewhere inside me—something as dark and hard as the rifle itself. Now when I sat on a log, the rifle across my lap had the feel and weight of a king’s scepter, and I felt the terrible thrill of power. Now when I was successful at blending into the woods, and a gray squirrel, scrabbling about in fallen hickory leaves for nuts, blundered close enough, I’d shoot it.

Why? For the thrill of power. For that terrible and awesome moment when I altered the world with the littlest movement of my finger. I, a shy, tongue-tied kid, might have been the czar of all Russia and the squirrel some fur-clad peasant trembling in my terrifying presence; I might have been Zeus himself unloosing thunderbolts on some unsuspecting mortal. But why had I killed the squirrel? I had no use for a dead squirrel. I wasn’t going to skin it, or eat it. It wasn’t a trophy I was going to bring home. There wasn’t even anyone I could brag to about my prowess as a hunter. Every time I shot one, I felt the same thing—even as I stood there holding my prize in my hand, I felt my pride draining away faster than the heat of its small body and, flooding in to take the place of my brief vanity, a guilty remorse and self-accusation.