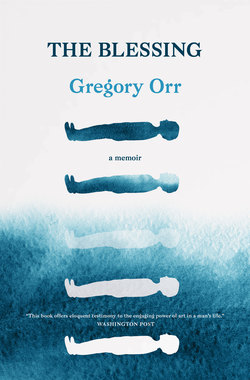

Читать книгу The Blessing - Gregory Orr - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление6

Numb

I was numb at the funeral. I remember almost nothing except a white curtain that was drawn to keep us, the family, separate from the rest of the mourners. We sat in a little alcove. I remember the chairs—the same folding metal ones I’d set up or folded countless times in the school gym or at Cub Scouts or in church basements. I don’t remember people, except as a kind of whispering around me. And where was I? I was deep in a desert wilderness as desolate as that inhabited by those early, God-tormented Christian saints who lived their whole lives alone on top of stone columns. Only I wasn’t on top of the column, I was embedded inside it, as if it were a shaft of pure shame transparent as Lucite, and I was immobilized inside it, like an insect or some unusual beetle. I heard people whispering around me like the desert breeze around the pillar, but I couldn’t move or look up, and so as far as I could tell no one was there.

The grave site was a two-hour drive from our town—across the Hudson and north into the Helderberg Hills southwest of Albany, where we had lived when I was first born. As we drove home, in the dark, I felt my faith in the devouring God grow stronger. I saw that Death, his angel, was everywhere, that it had entered our lives and I had opened the door to welcome it. I saw that it could enter in the spectacular, terrible form of Peter’s violent death, but that it could also insinuate itself in minor ways, in numberless tiny shapes you might not even notice until they had worked their way toward a beating heart in order to still it. Sitting in the dark in the back seat during that long drive, I saw that death was with us. It was the small white snail of wadded Kleenex my mother kept pressing against her face; it was nibbling holes in her cheek as if it were a leaf. I saw that death was the moonlight’s patch of blue mold growing on my father’s shoulder as he drove, oblivious, through the deep night.

When I tried to sleep that night and for years after, I could only do so if I began in one position: flat on my back with my arms crossed on my chest and my legs hooked over each other at the ankles. Lying like that in the dark room, in the pose of a mummy in an Egyptian sarcophagus, I calmed myself toward sleep. I imagined I was both the body inside, immobilized by its wrapping of thin linen strips, and the wooden case itself, painted with the expressionless face and figure of its dead occupant. I was afraid of my thoughts and afraid of the dark. I needed a double magic of rigidity to brace me against the violent storms of my dreams.