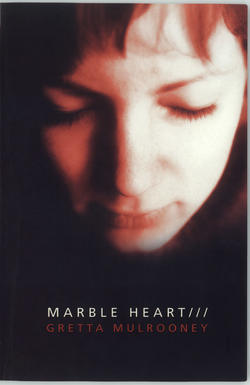

Читать книгу Marble Heart - Gretta Mulrooney - Страница 10

Оглавление4

NINA

‘Cara Majella,

‘Before I go any further, sifting through memories and years, I must tell you about the letter cards. The first one arrived a fortnight ago, the second this morning. I have them in front of me now. If I hadn’t already made the decision to open up the past they would frighten me more. Even so, they are alarming enough. I feel as if I’m being watched, my reactions monitored. When I received the first I sat frozen in my chair most of the day. As the sun faded I stared into the shadows and saw myself standing in a country lane, my feet mired in mud.

‘The cards are glossy productions, the kind that you fold over and seal. The photographs on the front feature views of phoney azure skies and intense landscape colours that rarely occur in Ireland. The peaceful rural scenes and wide stretches of picturesque strand flanked by hazy blue hills contrast oddly with the information inside. Both cards are a little creased because they have been typed. The first depicts panoramas of County Cork and I have read it so many times I could repeat it from memory:

‘I am stretched on your grave and you’ll find me there always; if I had the bounty of your arms I should never leave you. It is time for me to lie with you; there is the cold smell of the clay on me, the tan of the sun and the wind.’

It is no wonder that there are so many Irish laments and elegies, that so much keening has gone on here. You find it impossible to escape the past in Ireland. Everywhere you turn it surrounds you. You see it in the very shape of the country. You cannot go far here without stumbling over ruins and graves from previous times. Burial sites from prehistory stand silently on hills, watching the solitary walker. Graves hide under the vast boglands, waiting to be discovered by turfcutters. Passage graves, cairns, gallery graves, dolmens, wedge graves, killeens, court graves, portal graves, entrance graves, famine burials in cemeteries or under grass by the side of the road; the land is etched with random and ritual burials. The whole country is a series of catacombs. In the midst of life we are in death; that sentiment rings particularly true in this land where the dead keep close company with the living.

So many secretive graves, concealing the bones of those who died natural deaths as well as the many who were finished off by hunger or their foes.

In the view of Cork harbour, the second photograph, you can see Curraghbinny. It is a hill-top cairn, probably bronze-age. A clay platform inside it would have cradled the deceased but the body had disintegrated by the time the cairn was excavated. High up here, under a steely sky, it seems that the breeze carries cries of grief from that other time.

‘Can you imagine, Majella, how I felt when I picked up that first card? I was puzzled before I opened it and read the message. I know no one in Ireland these days; I could only think that one of my ex-colleagues was taking a holiday there. That line, you find it impossible to escape the past in Ireland resonated in my thoughts all day. An ambiguous you which could be interpreted both generally and specifically. I knew which way to take it, I repeated it to myself, over and over.

‘The card that came this morning was equally disturbing. Joan brought it in with the post when she arrived. I read it while she cleaned the kitchen. She sings while she works; verses from “Raindrops Keep Falling on my Head”, “Tea for Two” and other such jaunty numbers. This card is from Limerick and the first photograph shows Lough Gur, calm and sparkling in brilliant sunshine:

Megalithic tombs were built of huge stones and usually contained collective rather than individual burials. Bodies were buried singly, though, and you will still stumble on a lonely place where solitary bones have lain for centuries. Inhumation or interment of the corpse was usual although evidence of cremations has been found. Sometimes, with inhumations, bodies were exposed until the flesh had rotted and the skeleton was then buried.

The wedge grave was the first all-Irish grave form and you can see a fine example of one near the shore of Lough Gur. A couple of cremated bodies were found here but remains of twelve inhumations lay in the main gallery. The buried were surrounded by fragments of some of the good-quality eating vessels placed with them. Even now it is common to bury a loved one with some treasured possession. It is a way of soothing grief, imagining the departed helped on their way by familiar objects. The bereaved take comfort from it, feeling that they have established a link between the worlds of the living and dead. In a nearby churchyard today a musician being lowered in his coffin had his fiddle tucked in beside him. His wife stood by the grave, eyes brimming, lost in her sadness. She knows where her love lies, she will come back to hold vigil over him: ‘I would be a shelter from the wind for you and protection from the rain for you; and oh, keen sorrow to my heart that you are under the earth!’

‘I knew that I had been waiting for this second card. I know that there will be others. As Joan sang, “I’m gonna wash that man right outta my hair” I understood that my correspondent is determined to unlock my heart. Without warning, I felt that I might break down and release the swell of secrecy that I had harboured for so long. My eyes were scalded with tears but I heard Joan approaching and I composed myself, knowing that I mustn’t give in just yet.

‘In the early hours of this morning I have lain awake, wondering who is sending the cards. Whoever it is seems to be on the move, visiting chosen sites. I was always sure that only you, myself and Finn knew about our plan but now I’ve been imagining that one of the others found out or that you or Finn confessed to a comrade. There could have been a lonely hour, particularly after you split up, when one of you became desperate to share the guilt. Perhaps it was disclosed during pillow talk or maybe you told one of your brothers during a visit home, unburdening yourself while cleaning the hen house. But why would the confidant wait all this time to declare their knowledge? I have heard nothing about the comrades for years, with the exception of Declan. He was mentioned to me at a party and the unexpected confrontation with the past was extraordinary. I trembled as if a warning bell had clanged brutally in my ear. I’ve always assumed that our fellow revolutionaries became respectable middle-class professionals, much as comrades in England did, as I did myself; occasionally they might mention their madcap student days to one of their children or at a jolly supper, shaking their heads, smiling at memories of youthful radicalism. I recall reading that the leaders of the ‘68 Paris rebellion are now bankers, lawyers and TV executives. They featured in a Sunday colour supplement, sleek looking in soft chairs.

‘Then, as a cat yowled in the street at four AM I thought that perhaps your news of Finn’s death had been a mistake. Your cousin could have been confused and it would be easy to muddle facts long distance. What if there was a killing spree but Finn was only injured or he escaped the sprayed bullets and is now announcing himself? It’s the kind of thing he might do, don’t you agree, and a close brush with death can alter perspectives, make one look at priorities anew. My own illness has played no small part in my current actions. And Finn did so much love mystery and the rich weave of conspiracy, especially when they gave him the advantage. The typing points to him; he always typed, joking that everything about him favoured the left, including being left-handed but his handwriting was illegible through being forced to use his right hand at his boarding school. You would complain that his portable typewriter was like a prosthetic, often tucked beneath one arm. His clattering on the keys used to drag you from sleep early in the morning as he set about another day’s crusade. He is the only person I ever knew who would carry his typewriter to the bathroom, balancing it on his lap as he sat on the toilet.

‘I pictured him, perched in hotel rooms in Cork and Limerick, typing, still smoking untipped cigarettes. You may well have had cards too. I’ve no idea how he would have obtained our addresses but Finn was always an excellent information gatherer. Perhaps he is down on his luck and looking for a helping hand from old friends; he’d run through a fair part of his inheritance during the years when we knew him and he had expensive tastes despite his professed solidarity with the proletariat. His public face may have been in harmony with them but when he brought the shopping home he’d always bought the best lean steak and his claret was the finest in the wine rack. Or maybe he simply wants to talk about the past and being Finn, is coming in at a tangent, testing the ground. All these ideas might just be the wild products of a tired brain. I can only wait and surmise, see where the next card comes from. Living with uncertainty is hardly new to me.

‘You introduced me to Finn the day after I met you. “Come and listen to traditional music,” you said, “meet some interesting people.” It was the first time I heard the word craic; “the craic’s great at Mulligan’s” you explained as we headed through the dingy streets. I already knew then that I wanted to get as close to you as possible. You were sporting a fringed shawl and I touched one of the swinging tassels as we walked. I can still feel its warm, rough texture. I didn’t tell you I had never been in a pub, embarrassed by the extreme narrowness of the world I had inhabited. I remarked on the shabbiness around us, gesturing at boarded-up shops and broken glass in doorways. The contrast to leafy, prosperous Maidstone was shocking. I don’t think you ever fully understood how subdued and genteel my childhood had been. You had never visited England, had no way of knowing the culture gap I was experiencing. You replied that it was people, not buildings that mattered; come the revolution, when the proletariat triumphed, all these streets would take on new life and purpose and the equal distribution of wealth would mean that the populace had an investment in their surroundings. I was impressed by your certainty and the apparent imminence of the revolution. We passed an army patrol at a street corner, squaddies no older than ourselves with blackened faces and camouflage jackets that looked out of place in an urban setting. The first soldier said hallo civilly enough and instinctively I nodded back. The second quickly followed with a cockier, “hiya, darlings, wotcha doin’ tonight?” and you snarled back, “fuck off, you bastard shits.” I felt a quiver of fear mingled with excitement as he spat on the pavement. “Nothing to write home about anyway, lads,” one of them mocked behind us.

‘“Didn’t people welcome them with cups of tea and cake when they arrived?” I asked. I had seen photos in my mother’s Daily Telegraph; little boys perched on squaddies’ knees, fingering their guns while aproned women ferried teapots.

‘“A gut reaction of relief,” you said. “Now the military are exposed in their true colours, tools of the fascist state.”

‘In the pub you introduced me to people whose names and faces I no longer recall and we sat in a blue haze of cigarette smoke, listening to jigs and the roar of conversation. I was stunned by the chat which flowed seamlessly; people in England don’t talk to each other the way the Irish do, enjoying the flavour of words on the tongue. Despite the plain floorboards and cracked window glass the pub seemed exotic. I drank in the atmosphere along with my lager. I recounted the story of hiding in my room and described the other women surrounding me in the hall of residence. There were five of them, plump pasty-faced Protestant girls from local townlands I’d never heard of. Union Jacks and banners stating “No Surrender!” had been pinned to their doors. They dressed in white nylon blouses and dark pleated skirts, wore brown barrettes in their hair and plain, flat lace-up school shoes, the uniform of fervent Evangelists. Within days of arriving they had put hand-written notices in the communal bathrooms: “Please Remove Your Hairs From The Plug Holes” – I think it was the sight of pubic hairs that caused specific offence – and “Remember, No one Wants To Bathe In Your Tide Mark!” Perhaps the college accommodation service had thought that coming from England, I would be more comfortable situated amongst a group of students who were loyal to the crown. Early in the mornings they visited each other’s rooms to pray and sing fierce-sounding hymns in their rural Ulster voices:

“Awnwerd Crustyen So-o-oul-dye-erz!

Marchin’ az tuy wur,

Wuth the crawz of Jeezuz

Goin’ awn beefurr . . .”

‘I was sure I had detected a tambourine but there was no danger of “Mr Tambourine Man” drifting through the thin walls. I heard myself being witty as I described them. I had never before been the centre of attention in a group of people, never talked so much and so freely; I didn’t know you could become intoxicated with language. There are times when, clawing my way through a typically constipated English conversation, I find myself craving some of that old, easy jawing.

‘You talked and laughed that night but you were distracted and when Finn came in and you relaxed I understood that your tension had been that of a waiting lover. He was wearing dark clothes and a black beret. A pack of papers was stashed under his arm and he was in a foul mood. That testiness, that air that nothing ever quite pleased him was part of his attraction. Sales had been poor, he said, and Vinny hadn’t turned up to help him. He laid the papers on the table and I saw that they were thin bulletins, printed on a duplicating machine and that his fingers were smudged with dark ink. Workers’ Struggle, The Paper of Red Dawn, I read as I craned my neck and you told Finn my name. He nodded a brief hallo and went to get a drink.

‘“Is Finn your boyfriend?” I asked.

‘“My lover and comrade,” you corrected.

‘I gazed at you and then at Finn’s long back, impressed by this mysterious world I was glimpsing and experiencing a twinge of envy that you were involved with such an interesting-looking man.

‘Did I fall in love with Finn a little myself that night? I think I must have done, otherwise why would I have come to dislike him so intensely? He was dark and sure of himself; even his irascibility fitted a certain brooding stereotype and I had, like many another teenage girl, immersed myself in the Brontës and Du Maurier. When he came back with his drink he sat next to me and asked me questions about how I was finding Ireland. He tipped mixed nuts from a bag into his palm and offered them to me, saying I should pick out the almonds, they were the best. When the nuts had vanished he licked his salty hand as carefully as a cat licks its plate clean, running his tongue between his fingers. As he spoke to me he was examining my face. Although his eyes were a soft brown they had a directness that made me feel nothing would escape his attention. And nothing did, Majella, nothing did; he was watchful and always at the end of the road before we had turned the corner.’

Nina sighed and opened a new document, naming it ‘Martin’. She typed quickly, her eyes a little blurred.

‘You are beginning to understand that I left you not just because I am ill or contrary. If you are bewildered by me, well, that makes two of us. When you harbour a knowledge that cannot be revealed you feel set apart from the rest of humanity. There were times in the long nights when I longed to wake you, confess to you, beg your help. But I had no right to taint you.

‘Can you picture me in that pub? My hair was long and wild and sometimes I used to colour it so that it took on a hue like ripe red gooseberries. I wore pale pink nail varnish until Finn remarked that it looked cheap; he was a puritan about make-up although I expect he would have approved of the type of products you can buy now, recipes originating from far-flung populations of the third world.

‘That was a magic night in Mulligans; the kind of vivid experience you always remember with completeness: the sounds, the colours, the voices, the feelings engendered. On that night when I met Finn I started to feel a release of energy, a thrilling giddiness. It seemed to me that I had spent my days up to my eighteenth year in a timid stasis, waiting for something to happen. My mother’s message to me was enshrined in her stock phrase, “no fuss please, darling,” and my father’s self-effacement and premature death left a void.

‘In my mother’s shaded drawing room, behind ruched curtains, I had watched television pictures of Soviet tanks in Prague and rioting in the streets of London and Paris; demonstrations against the Vietnam War in Washington, civil rights marchers from Belfast with blood streaming down their faces, the reality barely impinging on me as I went about the discreet life lived in English suburbia, preparing to go to the tennis court or the library. I was dimly aware of Joan Baez singing “We Shall Overcome” and of the student power that was setting European streets ablaze. The only cold war I was familiar with was the one my mother had waged for years against my father, a series of frosty skirmishes that left me stranded in no-man’s land, unsure of who I should offer my loyalty to in any particular week. There were plenty of occasions when they communicated by leaving notes for me and I ran back and forth like a messenger between the trenches. My mother’s dugout was the drawing room, my father’s the potting shed. The events of 1968 took place while I was attempting and failing to broker peace somewhere between these camps, carrying communications written in codes which the two sides were doomed to misinterpret. If I paid any attention to them, it was with feelings of distaste and anxiety at such breakdown of order; locked as I was in the long disintegration of a marriage, I couldn’t face combat in the outside world.

‘In Mulligan’s bar I grew inebriated on the yeasty tang of stout and the fumes of golden hot whiskies in which cloves bobbed like tadpoles. I tried my first plate of boxty, the publican’s speciality, a dish that I became addicted to. It was hot, peppery and buttery and when someone said it was the food of the gods I agreed. A student who I later learned was Declan, the treasurer of Red Dawn, leaned across and asked teasingly if I’d heard that old rhyme:

“Boxty on the griddle

Boxty on the pan

If you don’t eat Boxty

You’ll never get a man!”

‘I smiled at him, registering that he had deep blue eyes but Majella reproved him, saying that we didn’t want to hear any of that old sexist claptrap. Finn took a spoonful from my plate without asking permission and declared that boxty was good, humble peasant food, the backbone of Ireland, the kind of dish that had its equivalent amongst working people in all cultures. A man stood up and sang a traditional ballad that brought tears to my eyes, a song about loss of land and family. Then Majella rapped the table and launched into a song that spoke of present injustice. She sang with such passion that I bit my gum through the boxty:

“Armoured cars and tanks and guns

Came to take away our sons

But every man will stand behind

The men behind the wire.

“Through the little streets of Belfast

In the dark of early morn

British soldiers came marauding,

Wrecking little homes with scorn;

Heedless of the crying children,

Dragging fathers from their beds,

Beating sons while helpless mothers

Watch the blood pour from their heads.

Round the world the truth will echo

Cromwell’s men are here again,

Britain’s name forever sullied

In the eyes of honest men.”

‘Afterwards, I asked her in a whisper if that was really happening and she said yes, nightly; men taken away and never charged, never given the chance of a fair hearing, their families left devastated. We were living in a tyranny but Bob Dylan was right, these were times of upheaval and change; this system of injustice couldn’t last, the people’s blood was up.

‘I understood that night that life had been racketing around elsewhere while I quietly occupied my little corner, mediating my parents’ antagonism and avoiding my mother’s censorious eye. In our tidy bungalow tucked away in a cul de sac it was a crime to leave an unwashed cup on the table, draw the curtains back untidily or spill a drop of liquid on the furniture. The background orchestration to my childhood had been the tight hissing from my mother’s lips as she heaped blame on my father or found fault with me. Now I was in a city where people opened their mouths wide to bellow their opinions and were willing to suffer terrible wounds, even death, for their beliefs. A sense of sheer animation, an impetuosity I would never have guessed at, was pulsing in me. I saw it reflected in Majella’s eyes, heard it echoed in her voice. The urge of something to aim for, something to risk everything for, that was what I wanted. The deliciousness of the boxty was giving me a taste for more flavours. I was ready for tumultuous change. I was ripe for falling in love and I did, with the scarred warring city and Majella and Finn.

‘When you are judging me, when you finally weigh up what you have learned, remember that the impulse was to do good, to create, to make a positive mark on the world. I fell far short of my own aspirations but I did possess them, and that remains some comfort to me.’