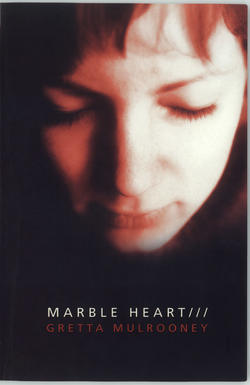

Читать книгу Marble Heart - Gretta Mulrooney - Страница 8

Оглавление2

JOAN

Joan spent the first week with Nina Rawle helping her to get her flat organised. Nina didn’t want to be taken out anywhere; she said she’d rather concentrate on ridding the place of the stacked cardboard boxes. She could do very little herself. The least exertion tired her. By the time Joan arrived each morning at nine she’d showered but the energy she had expended left her exhausted for an hour afterwards. Her hair never looked quite clean and at times Joan could see a sticky crust of lather on the crown of her head. Joan wondered about offering to help her in the bathroom but Nina had a reserve that made her think better of it.

While Nina sat reading the paper or listening to music or the radio Joan prepared her breakfast. She liked a small bowl of muesli or a poached egg on toast and fresh fruit; a segment of melon or a peeled orange or grapes. Joan had never come across this eating fruit for breakfast before; to her, fruit was for puddings or for when she was watching her weight and then she ate apples. For evening meals Nina requested blended home-made soups, pieces of chicken or fish with steamed vegetables or cheese or tomato soufflé followed by more fruit. She liked two glasses of wine in the evenings, French or Australian red from the rack in the kitchen. She invited Joan to have a glass, too, but it wasn’t to her liking. If Joan drank wine she chose a sparkling sweet variety; Lambrusco was her favourite: those bubbles tingling on her tongue spelled luxury.

At first, Joan found the shopping nerve-wracking. Nina’s list sent her searching for star fruit, lychees, artichokes, smoked applewood and goat’s cheeses, Greek olives, red snapper and lemongrass. Joan had never taken much interest in cooking and, as most of her clients were old, they liked the kinds of dishes her gran had preferred: tinned steak-and-kidney pies with mushy peas, jellied eels, liver and bacon with a thick cornflour gravy, sausage and mash and shepherd’s pie. They were meals she could make with her eyes closed.

She felt anxious for the first few days, examining the produce at the delicatessen counter in the supermarket, but there was a kind, motherly woman there who helped her out. Joan explained that she wasn’t used to this sort of shopping; with me, she said, it’s a quick whip-round for a jar of coffee, a couple of ready dinners, a boxed pizza and a packet of frozen peas. The assistant laughed, tucking a straying hair under her cap and told Joan that she could hardly keep up herself with the new lines they were always introducing. They had to have what was called familiarisation, she revealed; sessions with the section manager where they learned about the product and how to pronounce its name. When she was a young housewife you bought either Cheddar or Leicester cheese. Now it was Italian this and Norwegian that, soft and hard, pasteurised and unpasteurised and were we any the better off for it? Joan was reassured that she wasn’t the only one who’d never come across some of these alien foodstuffs.

It was years since she had been to a proper fishmonger’s. She used to go to the one in the High Street with Gran on Friday mornings to buy slabs of the waxy yellow haddock that she then poached in milk. Gran had stomach ulcers and ate a lot of what she called slop food: junkets, custards and milky sauces. One of her favourite dishes was fresh white bread squares sprinkled with sugar and steeped in warm milk with an egg whipped in. Nourishing, she called it. She used to feed that to Eddie, Joan’s brother, when his chest was bad but she never made it again after he’d gone. Joan couldn’t imagine what Nina Rawle would make of such a concoction. She specified the fish shop where she wanted Joan to buy the red snapper, salmon and trout she liked. The raw smell of the place made Joan gag; give me a boil-in-the-bag kipper any day, she thought, avoiding the staring cod eyes. The assistant who served her had wet chilled hands and his eyes bulged too. The right one had a cast, the pupil pale as if it had been bleached. She hurried in and out of there.

Nina took it for granted that Joan was familiar with all these foods and although this unnerved her it also afforded her a certain pride; she liked to think that she could keep her end up in any situation. When Nina handed her the shopping list Joan glanced at it and nodded. Out in the car she would sit and read through. Unfamiliar items such as Jarlsberg or Prosciutto made her frown but then she headed for the woman on the delicatessen and all was explained. Nina also gave exact instructions about how she wanted things cooked, which was just as well as Joan wouldn’t have known one end of an artichoke from another. She had never come across some of the kitchen utensils but she was quick off the mark with anything practical and worked out how to operate the asparagus steamer and the chicken brick. As she grilled monkfish or turned bean sprouts in a wok moistened with sesame oil she thought that she would serve some of these dishes to Rich and impress him. He’d grown up by the coast in Frinton so she imagined that he might be partial to seafood. He complained about the muck he’d had to eat over the years; there was never enough and it was tasteless, worse than school dinners. Joan wouldn’t try him with the fruit, though. She knew he liked what he called proper puddings: jam roly-polys and treacle sponges with thick custard.

After Nina had eaten her breakfast they got on with the boxes. Joan knelt on the floor and Nina sat by her in her chair, sneezing now and again as dust rose. If there was a spring chill in the air she pulled her old woollen shawl around her shoulders, plaiting the fringes over her knuckles. Sometimes Nina wore dark glasses when the light was particularly bright. She had them attached to a silver chain and they dangled on her chest when she took them off.

She had worked out ways of saving energy and keeping things to hand: there was the CD player clipped to her waist and the headphones around her neck. She also had a leather belt of the kind that Joan had seen carpenters store their tools in where she kept her tablets, eye drops, glucose sweets, tissues, a hip flask and a slim volume of Keats. She sucked glucose constantly, saying that it bucked her up. When Joan mentioned that the sweets might rot her teeth, she said flippantly that she didn’t think she was going to need teeth for that many more years. Joan was shocked, especially by the casual way Nina came out with it. She felt herself colouring up and said something about it being a warm day.

The boxes were mainly full of books, dozens of novels. Some of them were old, creased paperbacks with dark green and orange covers. Two boxloads were in French. Joan recognised the actor with the big nose on the front of one.

‘Goodness,’ she said to Nina, ‘have you really read all of these?’

‘Yes, most of them more than once.’

Joan flicked through one, glancing at the strange words. ‘I’m not much of a reader, although I like a magazine story. The best are those ones with a twist at the end. What language is this?’

‘Italian. I was a university lecturer in languages, French and Italian, for twenty years.’

‘Did you have to give up work because of your illness?’

Nina nodded. ‘These are just a fraction of the books I used to own. I got rid of a load of stuff before I moved here.’

‘I try to read,’ Joan told her, ‘but I can never settle for long. I always notice a bit of dusting that’s needed or a cushion cover that wants mending.’

Nina raised an eyebrow. ‘I don’t think I’ve ever mended a cushion cover.’

‘There’s real satisfaction in doing a neat job on a seam.’ Joan rubbed a book jacket with the duster. ‘I suppose I’d better watch my grammar, now that I know I’m around a teacher,’ she said, laughing. ‘You know, no dropping my aitches.’

‘I’ve just realised, I’ve put the cart before the horse here,’ Nina said. ‘I need bookshelves for all these volumes you’re unpacking.’

This fact had crossed Joan’s mind already but she had assumed that Nina had something organised on that front. ‘Those alcoves would fit shelves very nicely,’ she suggested. ‘We could get free-standing ones at the DIY place or if you want fitted I could do it, but I’d have to borrow a drill.’

Nina shrugged. ‘No, I can’t be bothered with drilling, that sounds too permanent. Where did you learn to put up shelves?’

‘I taught myself out of a book when I got my flat.’

‘You live on your own?’

‘That’s right, I’m a single gal.’ Not for much longer though, she thought; just three months to go. She and Rich would need a bigger place to live eventually but her little nest would be fine to start with. Now that it was all beginning to seem more real, she had started to imagine how it would be in the evenings, the two of them watching TV over a takeaway or deciding to catch a film. Sometimes she pictured him there on the sofa and chatted to him, telling him her plans.

‘Let’s go to the DIY place then,’ Nina said suddenly. ‘I’ll just get a jacket. You have time, do you?’

‘You’re my only client today.’ Mrs Cousins, who she usually visited on Tuesdays had died two nights previously but she wouldn’t mention that, of course. She found a tape measure and sized up the alcoves while Nina went to the bathroom. When she returned she smelled of Lily of the Valley.

Joan told her it was the perfume her grandmother had used. ‘Funny how a scent can bring a person and lots of little things about them back to you, isn’t it?’ she said.

Nina buttoned her jacket up, even though the day was warm. Her poor circulation meant that she felt chilly when other people were taking a layer of clothing off. She nodded agreement but offhandedly, as if she wasn’t paying attention. Joan hoped that she hadn’t thought she was being compared to an old lady and taken offence.

The superstore was only ten minutes away and the mid-morning traffic flowed lightly.

‘You’re a good driver,’ Nina observed, ‘very confident.’

‘Ten out of ten?’ Joan asked.

‘Well, nine and a half. It’s always important to leave a margin for improvement, give a student something to aim for.’

Joan was getting used to her dry way of talking. She could just see her at the front of a class. She’d have been the kind not to take any nonsense, although Joan supposed that university students didn’t misbehave.

‘Did you like teaching?’ she asked.

‘Oh, yes. But it all seems a long time ago. It’s only a year since I gave up work and yet I feel as if I haven’t stood in front of a group of students for much longer. I’d be frightened to now, I’ve lost the knack.’ She laughed. ‘It was hard going for my colleagues at my leaving party, they didn’t know what to say. It was difficult for them to wish me a happy retirement, after all. People generally don’t like illness, it makes them uneasy, reminds them their own lives are fragile.’

‘That makes me think of a little verse I know,’ Joan said: ‘“We only know that each day bears, Joys and sorrows, sometimes tears.” Do you know Grace Ashley’s poems? I love them, I cut them out of magazines and put them on my fridge; I always carry a few in my bag.’

‘No, I don’t think I’ve come across her.’

‘They’re only a couple of lines, each one, but they make you pause. She really sums things up in a nutshell. I find them comforting.’

‘I think I’ll stick to a glass of good wine for comfort. Which reminds me, I’d like to stock up at the off-licence later.’

When they parked Nina handed Joan her sticks, then pulled herself out of the seat, holding onto the door frame. Her fingers were long and bony. Joan heard her knuckles crack as she put her weight on them. Her nails looked at odds with the puckered skin around them; they were oval, beautifully shaped with perfect half-moons at the cuticles.

They walked slowly into the store and made for the shelving section. Nina went straight to the pine and selected what she wanted within minutes, a golden Scandinavian wood. The two sets of shelves came to four hundred pounds. Joan thought it must be nice to go for the best without hesitating. Maybe once Rich was in a job they would be able to rip out the chipboard in her living room and have pine. If he was able to get a job; no, she wasn’t going to think negative thoughts, she was going to put her best foot forward.

That evening Joan assembled the flat-pack shelves in the alcoves and cooked turkey with baby sweetcorn and broccoli for Nina’s meal. When she carried it through on a tray Nina was pouring a glass of wine for her, a sparkling white.

‘Here,’ she said. ‘I bought a couple of bottles of the stuff you like. Tastes like lemonade to me, but each to her own. Cheers!’

She looked exhausted after her outing. Mauveish smudges ringed her eyes and Joan noticed her hands trembling on her sticks. She was terribly touched by the wine.

‘You’d no need to buy this for me,’ she said, sipping.

‘It’s nothing, it humours me. Where are we up to with the books? The Ms?’

Joan was lining them up on the shelves in alphabetical order. ‘Alberto Morave next,’ she said. ‘Is he interesting?’

‘Moravia. I think so. The turkey is delicious. What do you have in the evenings? Do you visit family?’

‘No, I’ve nobody close, they’ve passed on. I usually eat on my own, a pizza or a chop, something quick. I quite like those low-calorie, ready-made meals. You can pop them in the microwave and they’re done in a couple of minutes. It’s not much fun, cooking for one.’

‘No. I used to find it a bore before I got married. The university had a staff restaurant which was excellent so I ate in there most days.’

‘Are you divorced then?’

‘Separated. Have you ever been married?’

‘Yes, only for a year, in my twenties. It didn’t work out. I don’t like living alone. I pretend to; you have to, don’t you? It’s like what you said about illness. People get embarrassed if you admit you’re lonely. I didn’t think Mr Right would ever show up but he has and we’re marrying soon.’ She heard Rich’s voice telling her it wouldn’t be long now. They planned to go to the registry office the week after he came out. Joan would have married him and waited for him – she knew other women in a similar position did – but Rich insisted that he wanted to be a free man before they tied the knot. Joan wasn’t going to explain any of that to Nina, though. There were certain things you didn’t confide to clients if you valued your job.

Nina gave a pained smile. ‘Sometimes it doesn’t work out even when you do meet the right person. It’s all a gamble, it can tear you apart.’

‘You’re tired, I reckon,’ Joan said, thinking she sounded low. Her voice was flat and there was a slide in it. ‘You’ve done too much today. A good night’s sleep will put a smile back on your face.’

Nina lowered her head and finished her turkey. She dozed for a while, the tray still on her lap. Joan didn’t move it for fear of waking her. She carried on quietly with the books, wondering how anyone could read this lot, thinking of all the hours of sitting still it would mean. Like her, Rich wasn’t a reader, which was a shame because it would have been a way of passing those long hours he complained about. Joan had to be on the go, doing something; a tapestry, some mending, cleaning windows, stripping the cooker. She was just like Gran that way, always up and active. She had never seen Gran sitting for long: ‘I’m as busy as a hen with one chicken,’ she used to say, zipping from room to room. The day before she died she was turning a mattress. Joan thought of Nina, alone here at night with just her books for company and little else to look forward to. It made a sad picture. She chatted to Rich inside her head, telling him that she was going to get on with decorating the living room when she got home. The whole place was going to be revamped before he arrived; she’d drawn up a timetable. The last time she had been to see him she’d taken colour charts and they’d chosen the emulsion. Rich suggested that she should wait until he was out and he’d help her but she said no, she wanted the place just so from their very first day together.

Joan and her brother Eddie went to live with their widowed grandmother in Bromley when she was three and he was eleven. Their father had died of a heart attack just before Joan’s birth and their mother was felled by cancer when Joan turned three. Gran had a two-bedroomed terraced house. She and Joan slept in the front bedroom, Eddie in the smaller back one. Gran worked long hours in the rag trade but she ran a tight ship at home and they all had their domestic jobs. Gran couldn’t stand even a speck of dust in the house. When the coalman came to shunt his sacks into the bin outside she covered the floors and furniture in the back room with sheets of newspaper. She craved an end-of-terrace house so that he could take his filthy, blackened hessian bags up the side alley but none ever came up for rent. She’d hover around him, warning him not to touch anything, monitoring his mucky boots. Sometimes, to annoy her, he’d pretend to lose his balance and her hands would fly to her face in silent agony.

The house was chilly during the day but on a winter’s evening, with the coal fire well stoked, there was nowhere cosier. When Gran arrived back from work they would make pilchards on toast and she’d tell them how she’d machined twenty skirts that day, or stitched three dozen collars. Sometimes she brought back clothes she’d got cheap because they were seconds. Joan was the first girl in the street to have a pair of loon pants and Eddie cut a dash in hipster trousers when they were just reaching the shops.

Joan was fifteen when Eddie disappeared. By then he had rented a tiny flat in Islington but he often stayed with them on a Friday or Saturday night and his room was kept ready for him. Gran would put a hot water bottle between his sheets on winter weekends to make sure that they were properly aired. His chest, weakened by bouts of childhood asthma, was easily affected by damp.

After they heard the terrible news Gran insisted on maintaining his room just as it was on the last Sunday morning they had seen him. She literally wasted away in front of Joan’s eyes, worn out with grieving for him. Joan would hear her crying in the night, deep sobs against the pillow in her bed by the window, sobs that went on month after month. Joan stopped crying after a couple of weeks. She seemed to have used up all her tears. She felt dry and tight inside and remote, as if nothing much would ever matter again. She didn’t know how to comfort her gran. She was a young fifteen, tongue-tied and awkward. What could she find to say to a woman of sixty-six who had raised two families and outlived a child and grandchild?

Her grandmother died when Joan was eighteen. She was alone in the world then apart from an aunt who’d rowed with Gran and kept her distance and a couple of cousins who’d moved out to Essex, shaking the dust of the inner city from their feet. They had never been one of those close cockney families who were supposed to inhabit London. Joan would wonder if those families ever truly existed – she had never met any of them. At times it occurred to her that she had been handed a raw deal, orphaned and then deprived of the two people closest to her. The sight of her single plate and cup on the kitchen table could make her heart knock.

Gran left her exactly one hundred pounds. Joan put it in a building society and carried on renting the house. She had left school at sixteen with four O-levels. The teachers said that she was good enough to stay on and do secretarial training, maybe head to college eventually. Eddie had been of that opinion too; he’d said that when the time came he’d help her choose a course. But then he’d gone, everything changed and Joan couldn’t see herself as college material. She didn’t have much self-confidence to start with and what had happened to Eddie made her inclined to keep her head down. The world seemed an unpredictable place. She preferred to tackle the small, domestic issues of life, move in a familiar groove where there were certainties. That was why the agency work suited her so well; things had to be done on set days at set times and this pattern rarely varied. The wider scene – politics, the environment, world problems, the chaos resulting from wars and famine – she ignored; other people were welcome to worry about and deal with those problems. She never bought a newspaper and watched only variety shows, soap operas and films on TV.

When she left school she went to work in a bakery, then in the ladies’ clothes shop where she stayed until she moved to Alice’s agency. At twenty-two she married Bernard Douglas, who had been in her class at school and turned up at her door now and again when he wasn’t driving long-distance lorries. It hadn’t lasted long and she had felt relief tinged with only a shade of melancholy when he had written from Düsseldorf to say he’d got a job based there and he wanted a divorce. She had married him because of panic, seeing that other women of her age were setting up home, choosing curtains and carpets. His motives were unclear. His absences had pervaded the house and even when he was there he imposed so little of himself on it that he left no vacuum when he took off for a trip to the continent. He was capable in a slow, unwitting way, good at practical tasks and she had confused this with dependability, ignoring the evidence that a man who chose to let his work regularly take him far from home might not have domestic interests at heart. The divorce left her with mended window latches, a new drain pipe and guttering. Occasionally she would recall the stale plastic-and-oil smell of his lorry cab and the duty-free brandy fumes he breathed on her as he came through the door.

Resolutely she put her mistake behind her, saved regular amounts and eventually had enough for the deposit on her flat in Leyton. It was on the first floor of a three-storey fifties block, one-bedroomed with no garden but she’d loved it the moment she had set eyes on it. There was a Grace Ashley verse that said:

Give me a room

And I will paint it with love’s loving colours,

Cushion it with heart’s ease

And it will be our cherished home.

Joan had worked those lines into a tapestry when she moved to her flat. It hung in its frame on the living-room wall. She went and read it over to herself on that night when Nina had appeared depressed about her marriage. It meant even more now that she was preparing a home for herself and Rich. The paint for the living room was standing ready inside the front door. They had selected white with a hint of buttercup for the walls and deep yellow gloss for the skirting board and radiator. Joan had spent the previous weekend stripping off the old wallpaper and putting up lining paper. When she told Alice what she was doing, her friend had offered to come and give her a hand with the painting. She was lonely herself, that was why she spent so much time at work. Joan understood that her business had replaced her family, who had abandoned her. Her one son had become a drug user, then joined a road protest group and was living up a tree somewhere. Her husband had taken off with his optician years ago, clearing out their joint bank account the day he left. According to Alice, all that had remained of fifteen years of marriage were his golf clubs and a stack of pornographic magazines stashed in the back of the wardrobe. It was generous of her to root so strongly for Joan and Rich, advising that they should grab whatever happiness came their way. Some people’s scars made them resentful of their friends’ good fortune.

Alice arrived promptly at eight that evening, dressed in overalls. She had brought her own roller and tray so that they could do two walls each.

‘How are you getting on with that new woman, Nina Rawle?’ she asked as they worked.

‘Okay. I thought she was a bit stand-offish to start with but it’s just her manner. She’s very weak physically. It must be terrible to be able to do so little when you’re comparatively young.’

‘What’s the matter with her?’

‘Something wrong with her tissues, that’s all she’s said so far. She moves like an old woman. I think she’s quite depressed.’

‘You’ll be good for her then, Joan, you’ll chivvy her along. We’re survivors, you and me, aren’t we? Get on and make the best of things.’

‘You have to, don’t you?’

‘Suppose so. Any vermouth going?’

Joan poured two glasses and they took a quick breather while they sipped.

‘It’s a lovely colour,’ Alice said. ‘Warm. I hope Rich appreciates all this. I’ll be having words with him if he doesn’t.’

‘I don’t think you need worry about that. He’s a smashing man, Alice, he really is. Will you be a witness when we get married? His brother’s agreed to be the other one.’

Alice raised her glass. ‘’Course I will. It will be a pleasure, as long as you promise me you won’t want to do anything daft like give up your job.’

‘No chance. I love the job. Anyway, we’ll need the money.’

They carried on painting, finishing by ten-thirty. Alice washed out the rollers while Joan wiped splashes off the skirting board.

‘That Nina Rawle,’ Alice said, ‘did she tell you who recommended you?’

‘No. It was probably Jenny Crisp, the young woman with the baby in Crouch End.’

Alice shook her head. ‘That’s what I’d assumed, but it wasn’t her. I know because she rang today and she said she hadn’t mentioned us to anyone. I’m sure we haven’t any other customers from Crouch End.’

‘I don’t know then. I must be more famous than I thought!’

Alice was sniffing the air. ‘There’s a very scented smell in this kitchen, sort of musky. What is it, some kind of air freshener?’

Joan pointed to the cantaloupe sitting on top of the fridge. ‘It’s that melon. Strong, isn’t it? They were on a special offer, I thought I’d try one.’

They had another vermouth as a nightcap and Alice left. Joan knew she wouldn’t be going straight home, though; she’d be calling at the office to check the answer-phone. She couldn’t wait to introduce Alice to Rich; she knew that they’d like each other. Her life felt good. For the first time in many years, everything was coming together. She raised her glass to Rich’s photo in the kitchen and said goodnight, sleep tight to him, as she always did.