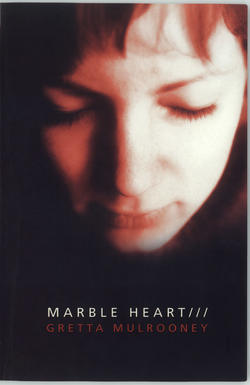

Читать книгу Marble Heart - Gretta Mulrooney - Страница 7

Оглавление1

JOAN

Alice Ainsley once told Joan that she always got a feeling in her bones when something was about to go wrong for her. It was like a dull ache, she said. She could sense in the morning if she was facing one of those days when the world was aiming to slide out of kilter. She felt like that the day her husband announced he was leaving and when her son rang to tell her he’d been arrested for possession of Ecstasy. Alice’s people had been tenant farmers in Somerset for generations. That was where she reckoned she got the knowledge in her bones from; it was inherited. Folk who worked the land needed a feel for all kinds of things. They had to be in touch with the world around them, the weather, their animals and crops. Her grandfather could tell if a cow was sickening from the feel of its ears and could forecast thunder, snow or drought. Alice had a habit of raising her nose and sniffing the air as if she were standing in a held, scenting rain.

Joan’s bones didn’t signal any warnings to her the morning she met Nina Rawle, but then she wasn’t from country stock. Her mother’s parents had worked in a garment factory in Bromley and her father’s family were street traders in Canning Town. No hairs stood up on the back of her neck as she parked the car outside Nina’s flat. She didn’t spot any black cats or magpies presaging disaster, there was no ominous rush of goose pimples on her skin. She walked in with a smile on her face, ready to do a good job. ‘Take people as you find them’ had always been among Joan’s numerous aphorisms, one of the many commonsense dictums she had heard from her Bromley grandmother. On that April day with the tart sap of spring in the air she saw in front of her a very sick woman who obviously needed help.

Alice was Joan’s employer and her friend, a combination that wouldn’t work in many situations but fitted the two women well. Joan had been on the books of the Alice Ainsley bureau for six years and knew the business thoroughly enough to run it on the rare occasions when Alice was unwell or took a quick break. They often had a glass of Martini in a little wine bar near the bureau, sweet red with lemonade for Joan, dry white with soda water and ice for Alice. Sipping slowly, they would discuss contrary clients and their problems with men, the major difficulty being the lack of them.

Maybe if Alice had met Nina, instead of just taking her phonecall, things would have turned out differently. If Nina had made her way slowly up the stairs to Alice’s office, leaning on her sticks, her hair swinging, Alice’s nostrils might have twitched. Detecting trouble, perhaps she would have told Nina that Joan’s schedule was full and offered her another assistant. Maybe, if, perhaps. Nina didn’t visit the office; she made a phonecall and Alice simply heard a cultured voice putting business her way.

Joan’s grandmother used to sing while she did the washing, a forties’ number: ‘If I’d known then what I know now I’d be a different girl’. She sang roughly but tunefully, tapping out a rhythm with her little nailbrush on the shirt collars as she worked carbolic soap into a lather. Nina reminded Joan of her gran, perhaps that was why she warmed to her so quickly. There was something about the no-nonsense way that Nina talked, her strong chin and firm lips, that summoned up Gran’s face. And of course there was the Lily of the Valley perfume; it was so unusual, so surprising to find a younger woman wearing it. It had been many years since Joan had sniffed that fragrance. The scent of it was strong the first morning she met Nina, calling up clear, happy memories.

Joan was feeling particularly well on the sunny Wednesday morning when Alice offered her a new client. She’d had blonde highlights done the previous day and her hair had a lovely shine. The locum doctor had given her a new prescription for sleeping tablets and he’d said, with an air of surprise that told her he wasn’t just trying to make her feel better, that she didn’t look forty. When the alarm rang at seven-thirty she realised that she’d had a good night’s sleep. That was always a bonus, like an unexpected present. Her face in the mirror was smooth, her eyes clear; anyone could see why a young man had given her a genuine compliment. She cleaned her little flat before she left for work, finishing with the kitchen floor. No good keeping other people’s places ship-shape if your own’s a mess, she always said.

She was full of energy as she ran up the steps to Alice’s office above the dry cleaner’s. Alice referred to it as the nerve centre. Joan had never understood how she managed to organise so many people from that tiny space. She supposed that Alice was just a natural although she did suffer: her voice was often scratchy with tiredness. Her nails were bitten ragged and she always looked a mess, her clothes thrown on any old how. It was just as well she didn’t often get to meet the public, dressed in her shapeless skirts and limp cardigans. Sometimes Joan used to think she lived in that office. She’d had calls from her at all hours of the day and evening. Alice derived huge enjoyment from creating rotas, writing in capitals with a black, thick-nibbed marker on the wipe-clean board which she divided up into weekly grids. She spent hours puzzling out the most cost-efficient use of staff time. That was her true talent, they’d often agreed. If Napoleon had had you, Alice, Joan would joke, he wouldn’t have lost Waterloo. Joan was a people person with a liking for hands-on contact and could always find a way of getting around even the most awkward of clients. They made a complementary duo and Alice’s acknowledgment of this was evidenced in the post of deputy manager she had created for Joan and the regular, albeit small, wage increases.

The office held one large desk and a sturdy metal filing cabinet with a phone and fax machine on top. There was a microwave, a kettle and a toaster perched on a shelf next to telephone directories. Alice was eating toast spread with jam and dragging a comb through her flyaway hair when Joan arrived. She saw a hair land on the dark jam and shivered; that kind of thing made her skin creep.

Alice didn’t have to soft soap her friend the way Joan knew she did with other staff, to get them to take on cantankerous old dears with more money than sense. She could depend on Joan, especially in a crisis. Some of the staff she employed were here today, gone tomorrow, leaving her in the lurch. A certain number of them just didn’t take to the work, others found something better paid. Joan prided herself on doing a thorough, efficient job. She had never had a day’s sickness, not even when the old dreams made her restless. She would arrive for work feeling heavy-eyed when she’d have liked nothing better than to burrow back under the bedclothes. It was important to her not to let people down. Rich said that she had the kind of face that made you want to trust her. When she tried to get him to explain what he meant he laughed, saying that she was just fishing for compliments. Alice appreciated her dependability. Joan had stepped in at the last minute quite a few times to pull the irons out of the fire; she was the only one willing to look after a boy with AIDS while his parents took a holiday. She had an album full of thank you notes from people she’d helped: the man with the broken pelvis, the couple who had the car smash, the girl with ME, to name but a few.

Working for the bureau was more than simply a job for Joan. Before she was taken on by Alice she had been employed by Mrs Jacobs, a widow in her late sixties whose first name Joan had never known, in an old-fashioned ladies’ clothes shop in Forest Gate. It was one of those places that the years seem to have ignored, a narrow-fronted shop with tangerine-tinted plastic taped inside the window to protect the stock from the sun. Buxom dummies displayed corsets, well-upholstered brassieres, pastel-coloured cardigans and shirtwaister dresses in man-made fabrics. The wooden drawers held a supply of support stockings in a shade of brown that reminded Joan of oxtail soup. By the till was a notice stating, PLEASE DO NOT ASK FOR CREDIT AS REFUSAL EMBARRASSES. Mornings were punctuated by Mrs Jacobs’ steaming Bovril at eleven and in the afternoons the malty odour of her hot milk drink hung over the acrylic jumpers. Joan measured customers’ bosoms and hips and discussed the qualities of triple-panel girdles while her employer wrote out price tags and talked on the phone to members of her Bowls club.

There had never been a great amount of custom and once the ageing female clientele started to die the doorbell rang less and less. Mrs Jacobs hinted that she didn’t need help any more so Joan took to scanning the job centre window.

The forced move had been a blessing in disguise. Living on her own, the evenings used to drag when she worked from nine to five. Alice paid more and Joan liked knowing that she would be out in other people’s houses some weeknights instead of sitting in with a glass of sweet vermouth, keeping the TV on for company while she worked one of her tapestries. Of course, since she’d got to know Rich she wasn’t available on Sundays any more. She had told Alice about the plans she and Rich had made for when they could be together. Alice was the only person she had confided in about their situation. Joan knew that she was discreet and broad-minded. Her own son had been in trouble a couple of times so she lent a sympathetic ear. Back then, Joan would have said that people who had suffered in life were more understanding; that was certainly true of Alice. But afterwards, when everything had fallen apart, she wasn’t sure of anything.

‘I’ve got a new lady for you,’ Alice said that morning, munching. ‘You’ll have to watch your Ps and Qs from the sound of her.’

If someone else had made that remark Joan would have taken offence but she was used to her employer’s sense of humour and knew that Alice appreciated all the times she’d put up with vulgarity and rudeness. The old boys were the worst, exposing themselves, pretending they couldn’t manage their underpants. Some of the old women were no better though; the ones who were losing their minds could be terribly crude. It was just as well that Joan’s attitude was one of live and let live.

Alice leaned forward with the details she’d written down. ‘She sounded very top drawer on the phone, not quite our usual customer. Her name’s Nina Rawle, aged forty-six. She needs someone every day.’

‘What’s up with her?’

‘She didn’t want to go into it when she rang, said she’d discuss things with you. She asked for you in particular, by the way, said someone recommended you.’

Alice gave her a satisfied smile. Word of mouth wasn’t unusual; quite a few clients came the way of the agency through the grapevine, especially people who’d had Joan working for them. Joan liked it when this fact was acknowledged, although she would always be quick to add that she wasn’t one to blow her own trumpet. When she saw Nina Rawle’s Crouch End address she decided that it was probably the woman who’d needed help with the baby a couple of months ago who had put her on to the bureau.

After she’d finished the usual formalities with Alice, Joan headed off to Crouch End. Before she started the car she pulled on her work tabard. Alice was rightly proud of it. She had designed it herself, in apricot polycotton with a cream trimming. It had AA on the front, in fancy gold lettering, which often brought a smile to clients’ faces.

The address Alice had given her turned out to be a big Edwardian house in a leafy street. It was divided into flats and Nina Rawle’s name was on the ground floor bell. Joan rang and waited. There was one of those spy holes in the door so she made sure she placed herself dead in front of it with the AA of her tabard showing. After some time the door opened slowly and a woman with grey shoulder-length hair and the biggest eyes Joan had ever seen was standing there, supporting herself on two sticks.

‘Good morning, I’m Joan Douglas from the Alice Ainsley bureau. Are you Mrs Rawle?’

The woman nodded and gestured with her head, already turning back into the house. ‘Close the door, will you,’ she said in a firm voice, the kind that Joan always thought of as BBC.

She stepped into a beautiful hallway, wide with polished floorboards and a huge gilt-edged mirror along one wall. The wallpaper was dark green, patterned with tiny red flowers, the kind that she guessed cost a day’s wages per roll. Classy, she thought; you’d need a bob or two to buy a place here. She followed Nina Rawle along the hall and through her own front door. Nina walked slowly, head bent, leading Joan to a long, high-ceilinged living room. The walls were freshly painted in pale cream but completely bare. There was a leather two-seater sofa, a recliner easy chair, stacks of boxes and at least two dozen plants in china bowls. The floor featured the same polished boards as in the hall, with one soft Persian rug covering the centre. A small table had one coffee cup and a lap-top computer on it. There was a slightly empty, impermanent feel to the room. Mrs Rawle might be moving in or out, it was hard to tell.

Nina lowered herself into the recliner chair, gesturing Joan to the sofa. The way she fussily settled her sticks next to her leg reminded Joan of an old woman and that was when she realised that this new client resembled her grandmother. She was wearing a dark blue tracksuit that obscured her shape but her body looked thin. Her face was pale; her cheeks marked with pink blotches, the skin stretched so finely that it seemed as if layers had been stripped away. Her neck was scrawny, her big eyes dull. You’re a poorly creature, Joan thought, but she said how lovely the carpet was because she liked to start on a positive note with all her clients.

‘Yes, I think so too,’ Mrs Rawle said, propping her arms on the sides of her chair. Her voice was the strongest thing about her. ‘It’s good of you to come so promptly. I’m sorry I can’t offer you tea but it would take me ages to get it. Maybe you’d like to make us both a cup in a minute.’

‘Of course,’ Joan said, ‘I suppose that’s why I’m here.’

‘You’re not bothered about routines, are you?’

‘Some like them and some don’t,’ she replied, guessing what was on Mrs Rawle’s mind. ‘My older clients prefer them but with younger people it’s different. Basically, I’m here to do whatever you ask.’

Mrs Rawle looked at her coolly. ‘Then could you take off that horrible apron? The colour reminds me of vomit.’

She stared, taken aback. ‘People tend to find it reassuring,’ she said.

‘I’m sure, but I’m not “people”. Really, it’s nasty, I can’t sit and look at it. Reminds me of hospitals, of officious busybodies.’

Joan undid the side ties and pulled it over her head, thinking she had a real nit-picker here. But as Alice never tired of saying, the customer’s always right. Over the years Joan had had a few classy clients like Mrs Rawle. They all shared the same tremendous confidence about coming straight out with what they wanted. Her gran used to say that toffs got their own way through sheer brass neck.

‘There,’ she said, ‘I shan’t wear it here again, I’ll leave it in the car.’

Her client positioned a cushion and sat back. ‘I’d like some tea now. Earl Grey for me with no milk. Please help yourself to whatever you want. I think there are biscuits in the tin. The kitchen’s through there.’ She switched on the portable CD player that was clipped to her waist, hoisting the head set draped around her neck up to her ears.

The kitchen was narrow, no bigger than Joan’s but beautifully fitted out in light oak with marble worktops. It was what Joan called slubbery: littered with bits of food, dirty crockery and saucepans. The tiled floor was tacky and the built-in hob had tomato sauce spilled on it. Her fingers itched to get cracking. Nothing pleased her more than to transform mess and clutter into sparkling order. A side door led from the kitchen to a good-sized sunny conservatory where there was a small pine dining table and four chairs covered in bits and pieces; candlesticks, glasses, papers, more boxes with china and a tea service. Around the floor stood a jumble of tall plants and by the far window a desk littered with folders and magazines. In spite of the mess the place had that understated, expensive sheen that meant the quality spoke through the grime. Joan’s poky flat was homely but she could only afford white melamine cupboards and a thin floor covering in her kitchen. If she let it get the slightest bit untidy it quickly took on a down-at-heel air.

She was about to take a look at the bathroom when the kettle clicked. She had never made Earl Grey before. The tea bag exuded a sickly perfume. She was looking to make a cup of coffee for herself but Mrs Rawle didn’t have any decent instant, just coffee beans so she settled for an ordinary tea bag which came from a Fortnum and Mason box. All the crockery matched, lovely white bone china with a blue flower but it was sticky to the touch and Joan thought that living in this mess must have been depressing for her new client. Then she said to herself that if anyone came into her home and found it in this state she’d be mortified, even if it had got that way because she was ill. But that was your middle-class confidence for you again. She searched for white sugar but there wasn’t any, just brown crystals that would taste of toffee. She remembered that she had a box of sweeteners in her bag.

Mrs Rawle was reading the newspaper but she put it down and switched off her CD player when she saw Joan.

‘Did you find everything?’ she asked.

‘No problem. I’m used to getting my bearings in other people’s houses.’

‘Of course.’

Mrs Rawle’s hair fell from a side parting, just skimming her shoulders. Joan thought it had probably been a dark brown before she went grey. In her opinion long hair didn’t suit middle-aged women, especially if it had faded. She had worn her hair long until she was twenty-eight; then she had it cut and layered and people remarked that she looked eighteen again. Mrs Rawle’s needed a good styling and a colour, one with a touch of bronze or mahogany to give her a lift.

Joan sipped her strong tea and asked her client if she had a garden. She replied that yes, the garden was hers, it went with this flat. She’d only moved in a month ago, that was why things were still disorganised.

‘I overestimated what I could do,’ she explained. ‘That’s partly why I’ve had to call you in. This is new to me, having paid help. What do your clients usually tell you on the first visit?’

‘Well, a bit about themselves and what they want me to do. If they’ve got a medical condition, they let me know if there’s anything I should be aware of.’ Joan preferred to say ‘medical condition’ rather than illness, especially with someone younger like Mrs Rawle. She thought it added a touch of dignity.

Mrs Rawle propped her chin on one hand. ‘I haven’t always looked like this, I didn’t have a collection of tracksuits because they’re easy to put on until fairly recently. I became ill three years ago; my tissues started fighting each other. I’ve got worse in the past six months. Most days I can do very little. That about sums it up. I want you to come in the mornings and get me some breakfast and any shopping I need, then again in the evenings to prepare supper. I need you to help me unpack all this stuff, get organised. I might like to go out once a week if I feel up to it. Does that sound negotiable?’

The way she listed it all, fast and crisp, she might have been asking Joan to be her secretary. She was a cool customer all right. Her big hazel eyes were very direct, almost uncomfortably so. It was only her body that was frail, Joan decided; there was a firm will inside that thin frame.

‘What about lunchtimes?’

She shook her head. ‘I want to have to fend for myself some of the day; can’t be going soft.’

Joan wondered where her family were. Maybe she’s like me, she thought, pretty much alone. There was no wedding ring on her finger but Joan could see a faint white strip there, as if she’d removed one in the recent past. She and her husband must be separated or divorced, Joan decided, unless he’d died. But widows didn’t usually get rid of their wedding rings, they clung to them. Mrs Waverley had been distraught because she couldn’t find her ring when her Harry dropped dead. Joan had searched high and low for it to no avail and in the end had lent her an ordinary signet ring she had been wearing.

‘That all sounds fine,’ Joan said. ‘I can’t do Sundays.’

‘Weekends are covered, this is a Monday-to-Friday arrangement.’

‘Have you had breakfast today?’ It was just on eleven.

Nina Rawle hesitated, then said no. She smiled at Joan, the first smile she’d given, as if she could relax now they had agreed terms. She’d like an egg, she said, and toast.

Joan got her what she wanted, wondering what her talk about her tissues amounted to; maybe she had cancer but couldn’t say it. People came out with all kinds of expressions to disguise illness; a man she had helped who had lung cancer always referred to his dodgy chest. She wiped things over as she waited for the egg to boil and made the toast nice, cutting off the crusts and slicing it into triangular shapes. When you’re ill, she thought, the little touches make a difference. She had noticed a patio rose planted in a tub in the conservatory, a bushy variety with orange-red blossoms. She nipped out and cut a single flower, putting it beside Mrs Rawle’s plate on the tray.

‘Oh,’ she said when she saw it, ‘how lovely! I’m not used to this kind of luxury.’

‘When I’m helping someone I like to attend to the details,’ Joan told her. ‘Now, tuck in before it cools down. Something tasty and hot is just the ticket when you’re not feeling too chipper.’

Mrs Rawle looked taken aback but she laughed. ‘Thank you, I will. Have you been doing this kind of work long?’

‘Six years, just on.’ Joan moved a plant which had tilted over on top of another.

‘And do you like it?’

‘Oh, yes, I love it. There’s always something new and I like meeting people.’

‘Some of them must be difficult, though – demanding.’

‘Well, sometimes. But I try to see the best side of people. You have to, and most clients are decent when you get to know them.’

‘Do you live near here?’

Joan chuckled. ‘Oh, I couldn’t afford this area. I’ve got a place in Leyton.’

‘Leyton.’ Mrs Rawle looked puzzled. ‘I don’t think I’ve been there.’

‘It’s okay, the only drawback is there’s no tube near but I’ve got Bessie – that’s what I call my car – so I’m not dependent on public transport. Now, shall I pop and tidy the kitchen while you’re eating?’

‘Please do. And could you see to the bathroom, too? I make quite a mess when I’m showering.’

There was an archway at the end of the kitchen, leading to a small tiled hallway. The bedroom was to the right, the bathroom on the left. It had a shower unit with a fitted seat, a bath, bidet and washbasin, all in the green of mint-flavoured chewing gum.

Quite a mess was an understatement. The floor was greasy with water and hair, toothpaste and soap clogged the basin. There was a perfume in the air that Joan recognised immediately. She lifted a bar of creamy soap and sniffed. Lily of the Valley. She could see that Nina Rawle had talc, deodorant and an atomiser, all from Selfridges. She used to buy Gran a tin of Lily of the Valley talcum powder from the Co-op for every birthday and Christmas. On the front of the yellow tin was a spray of dark green leaves with drooping delicate white flowers. Joan had thought it was the height of classiness. Gran’s name was Lily and she used to pull the front of her dress forward and shake the talc down her chest, saying, ‘Lily by name and Lily by smell!’ Then she’d tell Joan that she would be the most perfumed lady at the opera which would set her granddaughter giggling as Gran never went anywhere except to the whist drive. When Gran died and Joan was sorting her clothes, drifts of the snowy powder crept from the seams of her dresses and the perfume was all around her. Inhaling the scent of the soap took her right back to their dark little bedroom in Bromley with the gentleman’s oak wardrobe and the commode disguised as a chair. If Joan thought that she detected any omens that day, finding the Lily of the Valley seemed a good one. Then she gave herself a shake; she wasn’t being paid to stand and daydream.

She spent a good hour cleaning without even touching the conservatory. By then it was getting near the time she had to be at Mr Warren’s, so she washed up Mrs Rawle’s dishes and arranged to come back at six-thirty to cook supper.

‘There’s food in the fridge for tonight,’ Nina Rawle said. ‘I prefer light meals, soups and soufflés, snacks on toast, that kind of thing. I’d like some fruit. Could you possibly pick up a cantaloupe for this evening?’

Joan had never heard of a cantaloupe but she supposed they would have one in the supermarket. As Nina Rawle gave her the money she yawned, eyes watering. ‘Do excuse me,’ she said, ‘I don’t sleep well at night so I snatch naps during the day. I’m ready for one now.’

‘I sleep badly sometimes,’ Joan told her, ‘I have worrying dreams. Have you tried sleeping tablets?’

Nina looked uneasy. ‘Yes, but I don’t like taking them. Maybe I’m anxious that I won’t wake up.’

Joan didn’t believe in encouraging that kind of talk. ‘You’re just a bit down,’ she told Nina. ‘Try and get some rest and things will look brighter. Meeting someone new takes it out of you.’

Mrs Rawle gave another, fainter smile. ‘Oh, you haven’t tired me. I think we’ll get on, don’t you?’

Joan picked up her bag. ‘I speak as I find, and I think we can rub along very well, Mrs Rawle.’

‘We won’t stand on ceremony,’ came the reply. ‘You must call me Nina.’

‘Then you call me Joan.’

Nina Rawle was making her way carefully to the sofa as Joan left, leaning on her sticks, old before her time. She wore soft, Chinese-style slippers and the plastic soles made the lightest of taps on the floorboards, like a cat’s paws. There were only six years between them but there could have been twenty. Count your blessings, Joan told herself, heading for Bessie; you’ve got a good job and a neat little flat and Rich. She took a quick peek at the photo she kept inside her purse before starting the engine. Mr Marshall had kindly taken a snap of her and Rich with her own Instamatic. When Alice saw it she said they looked like peas in a pod because they both had round faces and Rich’s hair was the same shape, square-cut and layered. He came out quite blond in the photo although when you saw him in person there was a tiny bit of grey at the sides. Joan had warned him, as soon as she had her hands on him she’d tint that out. Mr Marshall laughed when he heard that and said could Joan pop in and do his for him sometime?

Sitting there outside Nina Rawle’s flat Joan thought that you met some good people in this world: Mr Marshall had been kind to Rich and of course Alice had been a brick about the whole thing. On the other hand, Mr Warren, the client she was about to see, was a real moaner; never a please or thank you but always quick to criticise if everything wasn’t just so. She gave Rich a kiss and tucked him away. There were another three days to go before she’d see him again but one of the advantages of having such involving work was that it made time fly.