Читать книгу Museum Transformations - Группа авторов - Страница 51

A boat, a crescent, and a flower

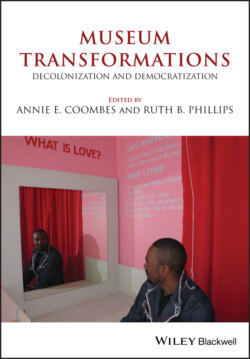

ОглавлениеA few months after Safdie and Badal met in Jerusalem, the architect visited Punjab. Touring the environs of Anandpur Sahib in a helicopter, Safdie rejected the plain ground that had been set aside for the museum, choosing instead a dramatic location on nearby sand cliffs. The museum would overlook the historic gurudwara where Guru Gobind Singh had baptized his followers, and its forms would both echo and play with the architecture of Sikh sacred structures. The designs that Safdie developed included a temporary exhibition hall, offices, and a seven-acre cascading water garden on the near side of the site. From the entrance plaza, a 540 foot long bridge would spring across a ravine to the museum proper, which would be housed in a cluster of structures ranged along the crest of the hill. These included an ellipsoid building shaped like a boat; a second building whose five towers joined to make a five-petalled flower-like roof (five being an auspicious number in Sikhism); and a third building whose sequence of square and triangular elements were arranged in a crescent (Figure 2.1). In profile, the buildings would recall the small forts built during Sikhism’s martial past; but the steel-clad roofs would be concave, as though revealing the inside of the domes that crown Sikh temples. According to Safdie, the complex’s buildings would express “the symbolic themes of earth and sky, mass and lightness, and depth and ascension (through the) … sandstone towers and reflective silver roofs” (Safdie Architects 2011).

Within months of the presentation of his design, Safdie was accused by the chief architect of the Punjab government of simply repeating the plans he had made for a museum in Wichita, Kansas. There, too, buildings with a similar thrusting skyline are arranged in a crescent, in a water body spanned by a bridge. Describing this accusation as “naive,” Safdie pointed out that he had used similar roof geometry not just in Anandpur Sahib and Wichita but also in Shenzhen and Singapore. This, he explained, was part of his personal architectural language.8

However, this accusation was not the only challenge Safdie was to face from architects in Punjab. Soon a prominent local architect persuaded the committee to insert his own memorial structure within Safdie’s complex. Intended as a quickly assembled feature that would be ready in time for the tercentenary celebrations the next year, this was to be a 300 foot tall steel alloy model of a Sikh ceremonial dagger that would be erected on a hill at the heart of the complex. Safdie reacted with dismay to this addition, which threatened to overwhelm his buildings. He reduced its size and shifted its location to the water gardens below. The local architect complained that Safdie had “buried” his feature, while Safdie countered that it now better harmonized with the complex and appeared to be “emerging out of the landscape.”9

FIGURE 2.1 Khalsa Heritage Complex, Anandpur Sahib. Architect Moshe Safdie. View of complex showing bridge, boat, and petal and crescent buildings from the water garden.

Photo: Shailan Parker.

We may interpret these controversies as expressions of the rivalries and resentments that can arise in any place when a prominent project is given to an outsider architect. But we may also see them as the manifestation of the irritations that arise between a global cultural form and its local context of reception. Since Badal had initiated the project by asking for a museum “just like this,” Safdie could justifiably assume that Punjab desired a “signature” building by him. As “starchitecture,” an important function of the building would be its ability to signal that it had indeed been designed by a famous starchitect. But in poorer countries, which have long been exploited by wealthy ones, suspicion is a habit. This might explain the objections of the first architect, who felt that Safdie was only recycling a previous project for India, much as charities distribute secondhand clothes in the “third world.” The second architect’s attempted introjection into Safdie’s complex could be seen as a refusal to accept starchitecture as privileged authorial form, immune to local interventions. Indeed, when arguing his case, the architect of the monumental dagger insisted on the value of local knowledge which alone could produce structures that would speak to the Sikh community.

Despite the occasional contention about the nature of the architecture, however, and despite erratic funding which resulted in tremendous delays, the building project was doggedly pursued. As the years went by, and the project fell nearly a decade behind schedule, the slowly rising buildings remained the only visible sign of the ambitious plans announced so long ago by the government to mark the tercentenary. Featured in newspaper articles (which mostly reported controversies, including many financial scandals and staff appointments and resignations) and on countless blogs (which mostly looked forward to the project’s completion), the architecture of the Khalsa Heritage Complex was always visible in the public domain. But the debates about its content were conducted in the privacy of committee rooms, studios, and offices, and remained hidden from view.