Читать книгу Museum Transformations - Группа авторов - Страница 59

A road not taken, and taking to the streets

ОглавлениеSince 2008, when Beijing prepared to host the Summer Olympics and pro-Tibet groups seized the moment to mount protests, a wave of resistance has been surging among Tibetans within and outside China’s Tibetan lands. Within China, resistance has met with severe repression, which has led to more desperate and extreme forms of protest. As the months pass, a terrible toll rises: of protestors who drench themselves with kerosene, drink the fuel, and burn themselves to death. At the time of writing, there have been 112 self-immolations. Most selfimmolators are young – in their teens or twenties – and many of them are monks or nuns. Even as the Chinese government attempts to control reportage of these self-immolations, news about them spreads via social media, occupies the international press, and evokes a horrified response that brings renewed visibility to the Tibetan cause. While many commentators characterize the immolations as violent or wasteful, the immolators’ own statements depict their act as an offering made for the greater good. Before he burned himself, Lama Sobha spoke of himself as a lamp: “I am giving away my body as an offering of light to chase away the darkness” (quoted in Sonam 2013, 96).

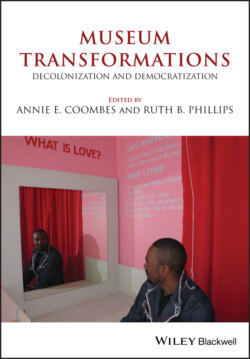

In response to the self-immolations, the Dalai Lama seems to be searching for a middle path, between honoring the martyrs and regretting the loss of lives in acts that he believes will have no effect on Beijing. Yet in the past few years, as the situation in the Tibet has escalated, several Tibetan exile groups have expressed disappointment with Dalai Lama’s Middle Way policy which accepts Chinese rule and only asks for greater Tibetan rights. Protestors also disagree with the government-in-exile’s focus on the future and the past rather than the present, on religion and culture rather than political realities. Where should these protestors go, when they seek a place for themselves that will serve not just as a place to meet but as a symbolic center that can articulate their frustration and their grief? In Dharamsala, when mourners gather to mark yet another immolation, they assemble in the street that leads to the Tibet Museum. This street now has an accretion of memorial sculptures wrought by many hands: a black obelisk erected by the Tibetan Youth Congress, a wall covered with a relief sculpture of protestors occupying a Tibetan map. The museum has become the pre-text for a thickening memoryscape dense with monuments to the tragedy of Tibet. A road not taken is now spilling into the street (Figure 2.6).

FIGURE 2.6 Street leading to the Tibet Museum and Dalai Lama’s Monastery, McLeodganj. The black obelisk is the Tibetan National Martyrs’ Memorial. The relief on the wall, showing protestors filling a map of Tibet, is by Lobsang Dhoyou, a former monk from Kham.

Photo courtesy of Latika Gupta.