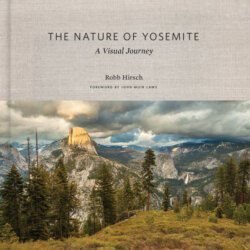

Читать книгу The Nature of Yosemite - Группа авторов - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеYOSEMITE FALLS

The rain stops, the clouds lift, and I run from shooting close-ups in the forest to one of the few locations on the Valley floor from which it’s possible to see both Upper and Lower Yosemite Falls. I have long wanted to capture an intimate image of these falls that also conveyed their size and grandeur. For fifteen minutes, I watch the clouds dance around the cliffs; then the sun pops through and the clouds briefly outline the upper fall. A colorful treeline of oaks just beginning to leaf out completes the scene.

For a fleeting time in late spring, the Valley echoes with the roar of Yosemite Falls’ cascading water; at full flow, an estimated 2,400 gallons (9,085 l) per second plunge 2,425 feet (739 m) to the base of the granite cliffs. They usually reach peak power in May; by August, the torrent—fed only by snowmelt—has been reduced to, at most, a trickle. The south-facing, hard-rock watershed has no lakes or wetlands to store water; when the spring flow is done, the waterfalls go quiet until the seasonal cycle brings them to life again.

CLEARING SPRING STORM

EL CAPITAN

Rising 3,300 feet (1,006 m), one of the largest exposed granite formations in the world, El Capitan dwarfs the surrounding landscape and is the Valley’s commanding presence. Its sheer face was shaped by the long-gone glaciers that slid slowly past and eroded the rock bit by bit, burnishing it smooth. Extremely hard and minimally fractured, El Capitan lures rock climbers from around the globe, eager to test their physical and mental strength against its smooth, unforgiving surfaces and overhangs.

EL CAPITAN AND THE MERCED RIVER IN WINTER

EL CAPITAN AND BLACK OAKS

Lying on my back in the meadow beneath El Capitan, staring up at the massive monolith, I can’t help but think about the concepts of size and scale. It is difficult to contemplate a feature so large, but there it is, right in front of me.