Читать книгу The Nature of Yosemite - Группа авторов - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

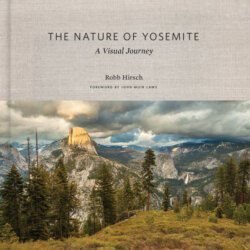

ОглавлениеYosemite

GRANTING THE LONG VIEW

BY ADONIA RIPPLE

I can find the shape of Yosemite on any map of the world. It’s in the heart of California. A boundary carefully drawn to contain the headwaters of both the Tuolumne and Merced Rivers. Of the twelve major river drainages that flow west out of the Sierra Nevada, how did the landforms of Yosemite end up so unequivocally beautiful? I know this answer intellectually: granite plutons, uplift, glaciers, river incision, succession of plant and animal species, and so on. But the Sierra is built of rock and water and plants and animals arriving at just the right time. There must have been some extra-special combination of elements that made Yosemite. No other river flowing west out of this range reveals such a perfect and ancient excavation, where the granite cleaves at just the exact angles to catch the sunrise and alpenglow for all the world to enjoy. The commanding profile of El Capitan, the hunch of Half Dome’s whale back, the serrated spire-topped Cathedral Range, where sharp mountain ridges escaped the crush of glaciation.

YOSEMITE VALLEY FROM THE SOUTH RIM

FLETCHER PEAK AND VOGELSANG LAKE

People store these shapes in their memory banks and let them soak into their DNA. Appreciation of these essential forms is passed down between generations. For both brand-new and long-term Yosemite lovers, these places seep into their minds and live in their bodies. Descendants look over dusty pictures of grandmothers long ago sitting in the same places as their now great-great-grandchildren, in a Yosemite changed yet unchanging. Something about that Yosemite-specific rise and fall of the horizon line draws us in. The distinct shape of Yosemite Valley triggers something deep in our primordial selves, offering a sense of being protected and inspired at the same time. It is a land that beckons you to come closer and listen. These universally gorgeous forms

Yosemite seems almost uniquely made to create a sense of comfortable humility

call to generation after generation. It called your parents’ parents to honeymoon, an uncle to camp at the river, families to return in recognition of life’s benchmarks—a special birthday, a college graduation, the birth of a child, the death of a parent. And on it goes; Yosemite receives us. It is big enough to hold our aspirations and our pain, to be our steady when all of life seems upended. Yosemite welcomes us to sometimes kneel, sometimes strive, sometimes just sit on that smoothed granite and feel the brevity of human life that only all that geologic time can reveal.

Yosemite has played host to my most formative life scenes. Ascending steep vertical walls and the resultant tears and smiles of a young climber’s early learnings. Dashing deeper into the winter wilderness on skis with storms nipping at my heels to high and lonely peaks. Freewheeling climbs with air under our feet over spiny granite ridges in the company of dear friends. And now, scrambling and rambling in the company of our young children and taking time to swim and throw rocks in those two rivers that flow west out of this most singular place on Earth. Again and again, in the most reassuring of ways, Yosemite shows me my life is small and that time moves along without much care for our victories and travails.

Yosemite seems almost uniquely made to create a sense of comfortable humility. It readily offers us the knowledge that our lives are so brief in comparison to the acts of granite making and glacier moving and big tree growing. With every distinct cliff face and treasured high-country ridgeline, Yosemite purveys perspective, encouraging the long view. There is comfort in knowing that under Half Dome’s gorgeous eternal gaze, human lives will ebb and flow. No matter how it turns out, a million more ruby sunsets will be catching that rock face long after we are gone. All this beauty will outlast us. There is infinite wisdom in that rocky place.

Adonia Ripple has lived and worked in Yosemite for more than twenty years. She came in on the floodwaters of 1997, when all her possessions still fit in a sedan and she could survive on seasonal work and sunsets. Forging her Sierra love affair as a mountain guide, Adonia has also worked as a naturalist, educator, and nonprofit director. She currently serves as the director of operations for Yosemite Conservancy, helping visitors from around the world connect with Yosemite.

STORM OVER HALF DOME

CATHEDRAL SPIRES

Winter is a special time in Yosemite Valley. The majority of visitors have gone, leaving a quiet solitude to explore, and when a storm blankets the terrain in snow, it creates the most magical wonderland.

Cathedral Spires, jutting up beside the south rim of the Valley, can be easily overlooked during most seasons, blending in as they do with the surrounding granite. But when outlined by snow, they seem to jump out of the landscape and make their presence known. During the last glacial period (the Tioga), the river of ice extended only partway up the Valley walls. These spires sat above the ice level and were thus spared the glacial scouring that shaped the granite below.

Winter is also cold in Yosemite Valley, but the opportunity to capture sublime moments makes numb fingers and toes worthwhile.

CATHEDRAL SPIRES REFLECTION

CLEARING WINTER STORM, THE MERCED RIVER AND CATHEDRAL SPIRES

FLOODED EL CAPITAN MEADOW

YOSEMITE VALLEY, SPRING FLOOD

In the spring, as the high-country snowpack melts and sends its water roaring down into Yosemite Valley, vast standing pools appear in meadows and other low-lying areas, overflow from the Merced River and its tributary creeks. This flush of water, a critical part of the Valley’s ecosystem, recharges the water table and deposits the nutrients and minerals upon which so many other organisms depend. The pools don’t last long, though; like giant sponges, meadows absorb the water and move it along on its hydrologic journey. So when they appear, I can often be found sitting nearby, watching waterfowl explore their expanded habitat and marveling at the way a horizon-to-horizon reflection makes an already majestic landscape even more grand.

UPPER YOSEMITE FALL AND THE MERCED RIVER AT FLOOD STAGE

MERCED RIVER, SUNSET

LIGHT

Light—it’s all about light. Because it can be difficult to predict where the best light will appear, especially when clouds are involved, I’m partial to photographing in locations that offer opportunities to shoot in different directions. I try to identify a variety of interesting scenes, prioritize them based on what I consider to have the best potential for a compelling image, then work through the list as the light changes.

Late on a November day on the Merced River, I start out facing away from this view, but the light in that direction remains relatively flat. Then I turn around: the sun is just starting to kiss the Valley walls, and the glowing clouds are bouncing illumination downward into the bottom of the Valley. I run to my predetermined option facing upriver, compose the frame, and take a deep breath, soaking in the view.

HETCH HETCHY

Scrambling around on the rocks and surveying the vast expanse of granite above the reservoir, I can’t help but wonder what this valley looks like under all that water.

Another magnificent and similarly formed landscape can be found less than 20 miles (32 km) to the north of Yosemite Valley. Originally a typical V-shaped canyon, carved by the Tuolumne River, Hetch Hetchy Valley was deepened, widened, and straightened into its current shape by successive glaciations. However, in contrast to Yosemite Valley, recent glacial periods filled Hetch Hetchy with ice to the brim and scoured its walls smooth, which is why it lacks the dramatic spires of its famous neighbor.

Prior to and, especially, following the devastating 1906 earthquake and fire, the city of San Francisco petitioned the federal government for rights to build a dam and develop the Tuolumne River for water security. Thus began a contentious national conservation battle (one that continues today). The city ultimately triumphed, and O’Shaughnessy Dam was completed in 1924, filling the valley with water for the Bay Area.

GRAY PINE (Pinus sabiniana) OVERLOOKING HETCH HETCHY

LEAF TRAILS

Rambling along the Merced River under a cloudy sky, I come across a colorful combination of rocks, moving water, and fallen leaves. I study the scene and formulate a concept for an image using a polarizing filter and long exposure times. Composing the frame, I partially rotate the filter to take in the reflection of the trees and cliffs as well as the rocks in the riverbed. Then I wait.

As leaves blown into the current from upriver trees float slowly toward me, I take a thirty-second exposure, which creates streaks. I repeat this process, one frame per gust of wind, for a few hours. When I’m done, I have eighteen images. In this shot, the position, direction, and flow of lines come together in a way far superior to the other frames. The Valley’s abundance of impressive icons can make these intimate scenes difficult to focus on, and as a result, I find them extremely rewarding challenges.

MERCED RIVER, AUTUMN

BRIDALVEIL FALL, WINTER

BRIDALVEIL FALL

Leaping over the edge of the south rim and plunging 620 feet (189 m) before eventually flowing into the Merced River, Bridalveil Creek feeds the first of several spectacular waterfalls visitors are likely to encounter when entering Yosemite Valley. Bridalveil Fall—a testament to the slow and magnificent forces of nature—typically flows year-round, thanks to a watershed filled with lakes, marshes, and groundwater-retaining meadows, as well as to its north-facing aspect, which means reduced evaporation.

Imagine the scene two million years ago: the floor of Yosemite Valley was near the top of the modern-day waterfall, and the creek was a simple tributary draining into a larger waterway. Then came the glaciers. Rivers of ice from the Tuolumne ice field repeatedly flowed into the Valley from both the Merced and Tuolumne crests, their massive weight cutting downward faster than the creek’s primarily water-driven erosional process. When the ice ultimately retreated, a hanging valley was left, a most striking and photogenic geologic phenomenon.