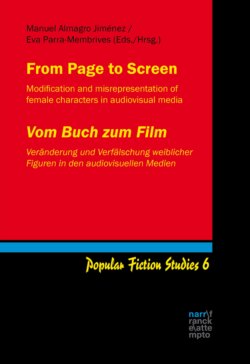

Читать книгу From Page to Screen / Vom Buch zum Film - Группа авторов - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3 For Women War is Never Over

ОглавлениеIn a conventional and simplistic view, it would seem that women are not directly affected by war, because war, traditionally, as we are used to seeing in novels, movies and history books, is something that only men experience. It is men who are part of the armies, who go to fight other men, who wait in terror in the trenches for the assault of the enemy, or leave them to kill their equally terrified enemies, or ride their horses in the mad frenzy of a cavalry charge, or are shot down from their planes during a bombardment by an anti-aircraft battery manned also by other men. If we think of the many stories of war in any format that we have been told, and with very few exceptions such as the presence of women in the Red Army in World War II, we will only remember the presence of men and their heroic deeds, their cowardice, misery, bravery, etc., alone or in a group with other men.

But, undoubtedly, this is a version that clearly falsifies the reality of things. Because if History is, so to speak, a huge canvas, what is shown in those stories is only a part of that canvas, and, in that sense, it is true that there are no women in that section of the image. But if only we shift our gaze a little towards the margins of the canvas, or towards less illuminated parts of the canvas, then we will begin to perceive that indeed women have been there all along, and that the problem was not that they were not there but that we were simply incapable of seeing them. Or even worse, we didn’t want to see them. Or even worse than that, we weren’t allowed to see them. Frequently, the writing of History works the way science does, with a strategy of trial and error, so that we could also say that History, at least serious History, is a story that far from attempting to write and define once and for all what happened in the past, it struggles to rewrite itself, precisely because of its bad conscience, that is, because it is (unconsciously) aware that its writing generates dark areas, because telling implies being silent, because emitting is omitting. Inevitably.

And when those dark areas are illuminated then we can see how women also have a close relationship with war. The women who in modern times occupy the factories and maintain the machinery of war in substitution of the men who had to march to the front, and the women who also participate, in one way or another, in the various aspects of war, an activity that does not restrict itself to the battlefield or the fight at the decisive moment. And also, like other segments of the population, the women who are frequently collateral victims of the consequences of war, both because they have to suffer the shortage of resources in the rearguard and/or because they are often victims themselves of the violence that any war generates, not the least of that violence being the more than frequent possibility of ending up as a plunder of war, in the usual form of a sexual assault, or as a trophy within the reach of a victorious soldier.

In this section of our collection we include three essays which only by chance happen to coincide in their focus and in the chronological order of their analysis: the situation of women in the period from the end of the First World War to the end of World War II. The first of these essays, by Alberto Lena, deals with the film version of a novel written by Erich Maria Remarque (Drei Kameraden, 1938) and its film version, Three Comrades, a Hollywood production directed by Frank Borzage in 1938. Initially planned as a woman’s drama, the film veers its course to become an indictment of the political situation and the violence which could be witnessed in Germany after, and because of, the First World War. Lena describes how, in the process of adaptation, the film becomes first an exploration of the social and economic context in which Adolf Hitler rose to power, and then also a vehicle for the representation of a German woman as a heroic subject.

Manuel Almagro-Jiménez concentrates his analysis on a climactic moment in the history of Germany, only a few years after Hitler’s rise to power. The fall of Berlin in 1945 at the hands of the Red Army led to the “inevitable” rape of around one hundred thousand women in that city. An anonymous woman captured the story of a number of them, registering their painful experience in her diary without any form of embellishment. The publication of that diary in 1959 was initially met with the rejection of a German society that refused to accept the reality of those facts. The later filmic adaptation could have vindicated the denouncement of the original text, but only served to aggravate the situation, as the tragic experiences of those women were buried under the typical language of melodrama. Almagro-Jiménez analyzes the film version of the diary in detail and highlights the additions found in that version creating a clearly melodramatic tone; at the same time Almagro-Jiménez draws attention to issues that are present in the diary but do not acquire sufficient relevance in the film, perpetuating the silencing of the true nature of these women’s experiences.

The last essay in this section, by Leopoldo Domínguez, concentrates on certain events that took place in the post-war period in Germany, and more specifically after the German reunification, also known as “Wende” (change). By means of the so-called memory literature, there took place an important re-evaluation of the most recent past, concerning issues such as victimhood and aggression, especially during the period of National Socialism. Domínguez by focusing on a specific text, Bernhard Schlink’s Der Vorleser, describes how this type of literature brings out repressed stories or traumas from the collective past for the first time. In contrasting the original novel with the film version, Domínguez discusses the difficulties involved in the adaptation of the novel and how in the film some of the most relevant issues are simply left out, as there is a preference for leading its narration towards the construction of a love story of sorts.