Читать книгу The Politics of Incremental Progressivism - Группа авторов - Страница 19

The City and Local Brazilian Institutions

ОглавлениеThis book analyses urban policies and politics in São Paulo. We are not centrally concerned with the main social, economic, and spatial characteristics of the city and their contemporary transformations, something we already analyzed in detail recently in another book (Marques 2016a). That book and the present one complement each other, creating a broad picture of the social, spatial, and political changes of the city since the return to democracy.

It is essential to present, however, some necessary information about Brazilian municipalities and São Paulo, as well as some short working definitions of the elements under analysis. Urban policies are understood here as the State in action (Jobert and Muller 1987) in what concerns primarily the production of the urban fabric – the physical and social space of the city – as well as the production of urban sociability. Urban politics, on the other hand, is defined as the conflicts, alliances, strategies, and mobilizations for and around urban policies, and the institutions that produce them and regulate political conflicts in the city.

Some doubt exists over defining the urban as either “local,” “of the city” or “municipal,” although the former may also include state‐level processes and the latter is too restrictive, excluding supramunicipal actions and processes. This imprecision is constitutive of the subject at hand, and the urban in this case is not merely a matter of scale, although it also encompasses elements of scale. Cities are both agglomerations and administrative jurisdictions (Post 2019) but incorporate actions and processes from other scales of governments (Le Galès 2020) whenever relevant.

However, most of the policies analyzed in this book are the responsibility of the municipal government of São Paulo. They are also, however, influenced by actions at other levels of the country's federal structure. The Brazilian Constitution recognizes municipalities as the third level of government, giving them specific policy responsibilities such as urban planning, licensing for buildings and settlements, intraurban transportation, local parks and sanitation (mostly conceded to state‐level public companies). Metropolitan railways, subways, and environmental control are state‐level policies, and there are no metropolitan‐level government structures. Policing is divided between the states and the federal government, while in housing, education, health, and social assistance, all levels of government contribute in some form. This shows the importance of federalism in Brazil, especially considering the policy systems created since the 1990s, combining centralization and decentralization (Arretche 2012). In some policy sectors, institutionalized social participation has played an important role, although more rarely in urban policies (Gurza Lavalle 2018). Finally, municipalities follow one single institutional format, as will be detailed through a comparative analysis in Chapter 1. They are governed by mayors and municipal councils, directly elected for four‐year terms since the mid‐1980s.16 Municipalities have access to a reasonable proportion of the nation's public budget, although, as we shall see in Chapter 3, only a small portion is available for discretionary allocation.

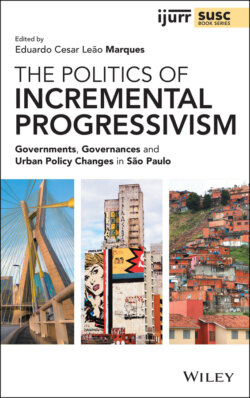

In 2010, the metropolitan region of São Paulo was home to more than 20 million inhabitants. Like other Latin American metropolises, the city was expanded by the large‐scale migration of poor people from less developed regions of the country during the decades of intense industrialization between the 1940s and the 1980s. Housing policies were fragile and selective, and in fact, the State did not provide even primary urbanization conditions for this population, who had to develop several types of precarious housing solutions to settle in the city. Between 1964 and 1985, the country was under authoritarian military rule with various regressive social effects. The redemocratization process was completed only in 1988 with the promulgation of a new, democratic constitution.

São Paulo's resulting urban structure was characterized until the 1980s by a well‐equipped central region, where the elites lived and circulated and where opportunities were concentrated, and increasingly precarious peripheries, where most of the population lived, typically in self‐built houses located in precarious settlements with a meager presence of State policies and equipment. The local literature (Kowarick 1979) analyzed classically these trajectories that became known internationally as informal housing and peripheral urbanization (Caldeira 2016). Migration processes and urban growth have both substantially reduced since the 1980s and essential political and economic transformations have been changing these spaces in the last decades. Formal housing market agents have expanded their production to these spaces (Hoyler 2016), made viable by the reduction in inequality occurring until 2015 (Arretche 2018), while wealthy residential enclaves were produced in these same peripheral areas (Caldeira 2000). The resulting segregation patterns, albeit transformed, still clearly present the durable superposition of class and racial inequalities in space (França 2016). Finally, the State became increasingly present in peripheries, providing infrastructure, services and policies, although usually of lower quality (Marques 2016a). A substantial part of these transformations was caused by the policies analyzed in the chapters of this book.