Читать книгу When Did we See You Naked? - Группа авторов - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

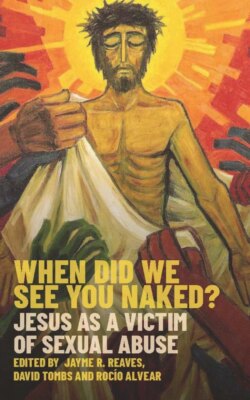

Оглавление1. Crucifixion and Sexual Abuse1

DAVID TOMBS

Introduction

The Bible is always read with a context in mind. Assumptions are made about the original social context of the text and these are most often derived – consciously or otherwise – from the current social context of the reader or critic.2 In recent decades the positive value of recognizing these connections has been advocated by contextual theologies in Latin America and elsewhere. Although some critics have rightly cautioned against temptations to superficially equate contemporary social contexts and the biblical world, those committed to a contextual approach have maintained that, when used appropriately, a serious engagement with current social contexts can offer insights into the biblical context and hence into neglected aspects of the biblical text.3

One area where I believe that shared similarities between past and present contexts can be most usefully investigated is the political arena of state terror and its use of torture. Latin American military regimes used terror in the 1970s and 1980s to create fear and promote fatalism throughout the whole of society. An understanding of this provides a context to recognize Roman crucifixions as instruments of state terror. Furthermore, Latin American torture practices involved deliberate attempts to shame the victims and undermine their sense of dignity. Physical torture and assaults were often coupled with psychological humiliation in attempts to end the victim’s will to resist, or even to live. Sexual assaults and sexual humiliation are a particularly effective way to do this, and are commonplace in torture practices past and present.4

This chapter argues that torture practices can offer a deeper understanding of Roman crucifixion as a form of state terror that included sexual abuse. The analysis below draws on Latin American reports, but a similar reading could be offered through attention to torture in many other contexts, including torture and prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib.5

To raise the question of sexual abuse in relation to Jesus may at first seem inappropriate. However, the Gospel accounts indicate a striking level of public sexual humiliation in the treatment of Jesus, and even this may not disclose the full horror of Jesus’ torture before his death. Although this may be a very disturbing suggestion at first, at a theological level a God who has identified with the victims of sexual abuse can be recognized as a positive challenge for contemporary Christian understanding and response. At a pastoral level it could help sensitize people to the experiences of those who have suffered sexual abuse and, in some cases, might even become a healing step for the victims themselves.

Crucifixion and state terror

Military coups in the 1960s and 1970s installed military regimes in Brazil (1964–85) and throughout the Southern Cone of Latin America (Chile 1973–89; Uruguay 1973–85; and Argentina 1976–83). During these years state-sanctioned human rights abuses, including torture, assassinations and disappearances, were commonplace. Likewise, in the 1980s the authoritarian governments in Guatemala and El Salvador were involved in some of the most brutal campaigns of repression the region has known. The transition to democracy in Brazil and the Southern Cone countries and the peace treaties in El Salvador (1992) and Guatemala (1996) have prompted official investigations into human rights abuses during the repression. Published reports from these countries offer detailed documentation that make grim reading on the years of terror endured by the civilian populations.6

Any understanding of the political and social dynamics of the countries during this time must address the widespread use of state terror to support and enforce the illegitimate power of military regimes. Terror was an effective means of enforcing brutal authoritarianism through a culture of fear.7 Fear ‘persuades’ people that it is better to endure injustices fatalistically rather than to resist them. The arrest and torture of ‘suspects’ by the police and military in Latin America cannot be adequately explained in terms of the threat they might have posed or the need to elicit information from them. Rather they should be understood as intended to paralyse a society’s willingness to resist. In addition to targeting the victims themselves, disappearances, torture and executions were intended to terrorize a public audience.

In a similar way, Roman crucifixion was more than the punishment of an individual. Crucifixions were instruments within state terror policies directed at a wider population in the ancient world.8 As acts of terror against potentially rebellious people, the Romans principally used crucifixion against slaves and other subjected peoples who might challenge Roman authority.9 One of the clearest illustrations of the use of crucifixion to inspire terror is provided by Josephus’ description of the treatment of those who attempted to flee Jerusalem during the siege by Titus in 70 CE:

Scourged and subjected before death to every torture, they were finally crucified in view of the wall. Titus indeed realised the horror of what was happening, for every day 500 – sometimes even more – fell into his hands … But his chief reason for not stopping the slaughter was the hope that the sight of it would perhaps induce the Jews to surrender in order to avoid the same fate. The soldiers themselves through rage and bitterness nailed up their victims in various attitudes as a grim joke, till owing to the vast numbers there was no room for the crosses, and no crosses for the bodies. (War, V. 446–52)10

The effectiveness and security of the Roman troops in Palestine was ultimately based on the legions in Syria and – if necessary – elsewhere in the Empire. The relatively small force in Palestine was able to maintain order because it was backed by an assurance of severe reprisals if serious rebellion broke out. The combination of moderate presence and massive threat was usually enough to preserve the so-called ‘peace’ of the pax Romana.

The mass crucifixions with which the Romans responded to major incidents conveyed the message of fearful retaliation with a terrifying clarity. Josephus describes how in 4 BCE Varus (governor of Syria) responded to the upheaval caused by the inept rule of Herod’s son Archelaus with the crucifixion of 2,000 ‘ringleaders’ of the troubles (War II. 69–79 [75]). The census revolt when Quirinius was governor of Syria (6–7 CE) and Coponius procurator of Judea (6–9 CE) also met with widespread reprisals (Ant. 18.1–10; War II. 117–18). Josephus also records that when Cumanus (procurator of Judea 48–52 CE) took a number of prisoners involved in a dispute, Quadratus (governor of Syria) ordered them all crucified (War II. 241). Likewise, when Felix (procurator of Judea, 52–60 CE) set out to clear the country of banditry, the number that were crucified ‘were too many to count’ (War II. 253). Josephus also records how, in the build-up to the revolt of 66 CE, Florus (procurator 64–66 CE) raided the Temple treasury and then – because of the disturbance that followed – scourged and crucified men, women and children until the day’s death toll was 3,600 (War II. 305–08).

Individual crucifixions should be understood within this political context. Even if only one victim was crucified, the execution had more significance than the punishment of an individual victim. Crucifixion was an important way in which the dire consequences of rebellion could be kept before the public eye. Individual crucifixions served to remind people of the mass crucifixions and other reprisals that the Romans were all too ready to use if their power was challenged.

There are few detailed descriptions of how crucifixion took place – the Gospels provide the fullest description in ancient literature – but the picture that emerges fits the profile of public state torture very well.11 The victim was tied or nailed to a wooden cross to maximize their public humiliation: a contrast of the shame of the victim with the might of imperial power. The Romans displayed the victim on a roadside or similar public place. Crucifixion was a protracted ordeal that might last a number of days, a sustained attack on the dignity of the human spirit as well as the physical body.12 The shame for Jews was further heightened by the belief that ‘anyone hung on a tree is under a curse’ (Deut. 21.23), a curse that Paul refers to in relation to Jesus’ crucifixion in Galatians 3.13.

Crucifixion and sexual abuse

Testimonies to torture in Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Central America and elsewhere consistently report stripping and sexual abuse as part of torture.13 In Brazil torture by electric shock invariably included shocks to the genitals.14 The same focus on the genitals was shown in Argentina. The preferred instrument for administering electric shocks in Argentina, la picana (a small electrified prod), is itself highly suggestive of the sexual element in this torture.15 Its use in the rape and sexual abuse of women has been well documented and at least two Argentinean male victims also witness to how this abuse eventually led to anal rape.16

For a reading of crucifixion, two elements of these torture practices deserve particular attention. First, sexual assault and humiliation were standard practices in state torture practices; sexual abuse was standard rather than unusual or exceptional. Second, the awareness among a wider public of a victim’s sexual humiliation was often an important part of this humiliation.

Against this background, the crucifixion of Jesus may be viewed with a disturbing question in mind: to what extent did the torture and crucifixion of Jesus involve some form of sexual abuse? The testimonies from twentieth-century Latin America create hermeneutical suspicions that merit careful examination of the Gospels to see whether there is any evidence that this was the case.

To explore this question further, it is helpful to distinguish between sexual abuse that involves only sexual humiliation (such as enforced nudity, sexual mockery and sexual insults) and sexual abuse that extends to sexual assault (which involves forced sexual contact, and ranges from molestation to penetration, injury or mutilation). The Gospels clearly indicate that sexual humiliation was a prominent trait in the mistreatment of Jesus and that sexual humiliation was an important aspect of crucifixion. If this is the case, the possibility of sexual assaults against Jesus will also need to be considered. In the absence of clear evidence to decide this one way or another, I will suggest that what has proved so common in recent torture practices cannot be entirely ruled out in the treatment of Jesus.

Crucifixion in the ancient world appears to have carried a strongly sexual element and should be understood as a form of sexual abuse that involved sexual humiliation and sometimes sexual assault. Crucifixion was intended to be more than the ending of life; prior to actual death it sought to reduce the victim to something less than human in the eyes of society. Victims were crucified naked in what amounted to a ritualized form of public sexual humiliation. In a patriarchal society, where men competed against each other to display virility in terms of sexual power over others, the public display of the naked victim by the ‘victors’ in front of onlookers and passers-by carried the message of sexual domination. The cross held up the victim for display as someone who had been – at least metaphorically – emasculated.17 Depending on the position in which the victim was crucified, the display of the genitals could be specially emphasized. Both Josephus and the Roman historian Seneca the Younger attest to the Romans’ enthusiasm for experimentation with different positions of crucifixion.18 Furthermore, Seneca’s description suggests that the sexual violence against the victim was sometimes taken to the most brutal extreme with crosses that impaled the genitals of the victim. This practice might never have been the case in Palestine – and there is no evidence that suggests it happened to Jesus – but at the very least it suggests the highly sexualized context of violence in which Roman crucifixions sometimes took place.

The sexual element in Roman practices was part of their message of terror. Anyone who opposed the Romans would not only lose their life but also be stripped of all personal honour and human dignity. It is therefore not surprising that the Gospels themselves indicate that there was a high level of sexual humiliation in the way that Jesus was flogged, insulted and then crucified. From evidence of the ancient world it seems that flogging the victim in public while naked was routine. Mark, Matthew and John all imply that this was also the case with the flogging of Jesus.19 Likewise, as noted above, crucifixion usually took place while the victim was naked and there is little reason to think that Jesus or other Jews would have been an exception to this.20 If the purpose was to humiliate the victim, full nakedness would have been particularly shameful in the Jewish context.21 Furthermore, prior to crucifixion, Jesus was handed over to a cohort of Roman soldiers to be further humiliated (Mark 15.16–20; Matt. 27.27–31; John 19.1–5).22 All the Gospels apart from Luke report that the Roman soldiers mocked Jesus by placing a crown of thorns on his head (Mark 15.17; Matt. 27.29; John 19.2) and clothing him in a purple (Mark 15.17; John 19.2) or scarlet garment (Matt. 27.28).23 The texts also mention that the soldiers spat at Jesus (Mark 15.19; Matt. 27.30), struck him with a reed (Mark 15.19; Matt. 27.30), and mocked him with verbal taunts (calling him king: Mark 15.18; Matt. 27.29; John 19.3) and symbolic homage (kneeling before him, Mark 15.19; Matt. 27.29).24

Based on what the Gospel texts themselves indicate, the sexual element in the abuse is unavoidable. An adult man was stripped naked for flogging, then dressed in an insulting way to be mocked, struck and spat at by a multitude of soldiers before being stripped again (at least in Mark 15.20 and Matt. 27.31) and reclothed for his journey through the city – already too weak to carry his own cross – only to be stripped again (a third time) and displayed to a mocking crowd to die while naked. When the textual presentation is stated like this, the sexual element of the abuse becomes clear: the assertion is controversial only in so far as it seems startling in view of usual presentations.25 The sexual element to the torture is downplayed in artistic representations of the crucifixion that show Jesus wearing a loincloth. These images distance us from the biblical text, perhaps because the sexual element has been too disturbing to confront.

Although it is vital to acknowledge the sexual humiliation that is revealed in the text, what the texts might conceal may also be significant. There may have been a level of sexual abuse in the praetorium that none of the Gospels immediately discloses. This suspicion is prompted by the testimonies from Latin America presented earlier. While the testimonies from Latin America do nothing to directly establish the historical facts of crucifixion in Palestine, they are highly suggestive for what may have happened within the closed walls of the praetorium.26

Both Matthew and Mark describe Jesus as being handed over weakened and naked – already a condemned man without any recourse to justice – to soldiers who took him inside the praetorium and assembled the other troops.27 Both Gospels explicitly state that it was the whole cohort (holēn speira) of Roman soldiers – about 500 men – that was assembled together to witness and participate in the ‘mockery’. This probably included a significant number of Syrian auxiliaries who might have viewed their Jewish neighbours with particular hostility.28 In view of the testimonies to gang rape that are given by victims detained by security forces in the clandestine torture centres of Latin America, this detail of overwhelming and hostile military power sounds a particularly disturbing note.

Many in the Roman cohort would have experienced the fears and frustrations of military life in an occupied country, which could have generated an awkward inner tension of omnipotence and powerlessness. As representatives of imperial Rome, the soldiers collectively exercised almost unlimited power. On the other hand, each individual soldier was at the bottom of a long chain of Roman hierarchical command and would also have felt their individual powerlessness on a daily basis. The instinctive response to such powerlessness is often to impose one’s own power forcefully on those who are even less powerful. Individual soldiers had very little freedom or personal choice to act on this, however, and often their interactions with local people would reinforce their feelings of powerlessness and frustration. The common soldier would often have to suffer without taking immediate revenge when faced by lack of co-operation, disrespect or barely concealed hostility. The resentment created by this situation would normally have been held in check by military discipline and the fear of military superiors who wished to avoid unnecessary trouble wherever possible. Nonetheless the aggressive urge to vengeance would remain close to the surface and could give rise to extreme violence when superiors were willing to turn a blind eye or sanction its expression on a sacrificial victim. The desire to take out the frustrations and brutalities of military life through sexual violence has given rise to atrocities throughout history.

Josephus’ account of the Siege of Jerusalem (War, V. 420–572) suggests that the comparisons between the ancient world and twentieth-century Latin American torture practices may be appropriate. Josephus’ description of how the Jewish militants inside Jerusalem tortured the civilian population in the search for food provides a graphic insight into sexual tortures at the time: ‘Terrible were the methods of torture they devised in their quest for food. They stuffed bitter vetch up the genital passages of their victims, and drove sharp stakes into their seats’ (War, V. 435). Although the actual historicity of Josephus’ claims can hardly be taken for granted (since Josephus was writing for a Roman audience and his exaggerations and vested interest in casting the Jewish rebels in a poor light affects his testimony throughout his account), it nonetheless suggests that the sexualized tortures of twentieth-century Latin America might correspond quite closely to their first-century Mediterranean equivalents. Likewise, Plato’s description in the Gorgias of a hypothetical crucifixion (preceded by torture and castration while on the rack) indicates that castration might have taken place prior to crucifixion in at least some parts of the ancient world.29 Furthermore, the historian Richard Trexler has claimed that the anal rape of male captives was ‘a practice notoriously rife in the ancient world’.30 In view of this background it is important to ask whether the fraternal and respectful kiss of greeting in the Garden of Gethsemane might have set events in motion that led to some form of sexual assault in the praetorium of Pilate.31

The privacy of the praetorium makes it unrealistic to expect a definitive answer on what exactly happened inside. Nonetheless, the suspicions raised by the experiences of those who have suffered under recent Latin American regimes suggest that a question mark needs to be put against the completeness of the Gospel narratives at this point. There is a possibility that the full details of Jesus’ suffering are missing from the Gospel accounts. Whereas the texts offer clear indications of sexual humiliation, the possibility of sexual assault can only be based on silence and circumstance. However, it should be remembered that although a distinction in sexual abuse between humiliation and assault is helpful, there can also be considerable overlap between them and the two tend to go together. In sexual torture, sexual assault is a form of sexual humiliation par excellence and sexual humiliation often rests on the threat of physical or sexual assault. What form of sexual assault – if any – might actually have taken place may be impossible to determine but the possibility needs to be recognized and confronted more honestly than has happened so far. To shed light on this, further historical investigation into the treatment of condemned prisoners by Roman soldiers and the treatment of Jesus in particular is obviously required. If this is to happen, however, it is appropriate to pause and ask what positive purpose these lines of enquiry will serve.

Theological and pastoral perspectives

I have found the direction my research has taken me to be very disturbing and I realize that others will feel the same way. I believe, however, that for Christians today these issues might serve constructive purposes in the theological and pastoral fields. Both our resistance and our openness to this line of enquiry might lead to insights and discoveries.

First, at a theological level, confronting the possibility of sexual abuse in the passion of Christ might deepen Christian understanding of God’s solidarity with the powerless. Sexual abuse is a destructive assertion of power. It shows the degrading consequences that distorted power can generate in human society. An important element in Christian doctrine has been that Jesus confronted the power of evil and suffered death on the cross as a result. The views presented here – that Jesus was a victim of sexual abuse in the sexual humiliation he underwent and he may even have been a victim of sexual assault – are deeply distressing. They may, however, offer insights into a fuller Christian understanding of a God who is in real solidarity with the powerless and suffers the worst evils of the world. An a priori judgement that Jesus did not and could not suffer sexual abuse may accompany an unexamined assumption that Jesus was not in fact fully human, a form of the Docetic heresy which denies the real form of Jesus’ physical suffering. Refusal to accept that Jesus could have been sexually abused suggests a refusal to accept Christ’s full incarnation into human history. To say that Jesus could not have been vulnerable to the worst abuses of human power is to deny that he was truly human at all.

At the pastoral level, confronting the possibility of sexual abuse in the passion of Christ could provide practical help to contemporary victims of torture and sexual abuse. Recognition of sexual abuse in the treatment of Jesus could bring a liberating and healing message to the women, children and men of Latin America, and elsewhere, who have also been abused. The acceptance that even Jesus may have suffered evil in this way can give new dignity and self-respect to those who continue to struggle with the stigma and other consequences of sexual abuse. A God who through Christ is to be identified with the hungry, the thirsty, the stranger, the naked, the sick and the imprisoned (Matt. 25.31–46) is also to be identified with those suffering abuse and torture in the contemporary world.

Conclusion

Despite the potential pitfalls, the dynamics of state terror in Latin America and other countries can be a fruitful starting point for insights into the Gospels. An awareness of human rights abuses in Latin America can yield important insights into the political context and full horror of Jesus’ crucifixion. The role of crucifixions in the production and maintenance of state terror and the element of sexual abuse in Roman practices require further investigation. The Gospels indicate a high level of public sexual humiliation in the treatment of Jesus and the closed walls of the praetorium present a disturbing question about what else might have happened inside.

References

Archdiocese of Sao Paulo, Torture in Brazil: A Report by the Archdiocese of São Paulo, New York: Vintage Books, 1986.

Boff, Clodovis, Theology and Praxis: Epistemological Foundations, Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1987.

Brown, Raymond E., Death of the Messiah, New York: Doubleday, 1994.

Corradi, Juan E., Patricia W. Fagen and Manuel A. Garretón, eds, Fear at the Edge: State Terror and Resistance in Latin America, Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 1992.

Graziano, Francisco, Divine Violence: Spectacle, Psychosexuality, and Radical Christianity in the Argentine ‘Dirty War’, Oxford: Westview Press, 1992.

Hengel, Martin, Crucifixion in the Ancient World and the Folly of the Cross, Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press; London: SCM Press, 1977.

Josephus, The Jewish War, trans. G. A. Willon, revised ed., Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1970.

Moore, Stephen D., God’s Gym: Divine Male Bodies of the Bible, New York: Routledge, 1996.

National Commission on Disappeared People, Nunca Más: A Report by Argentina’s National Commission on Disappeared People, Boston, MA, and London: Faber and Faber, 1986.

National Commission on Truth and Reconciliation, Report of the Chilean National Commission on Truth and Reconciliation, Notre Dame, IN: Centre for Civil and Human Rights, Notre Dame Law School, 1993.

Scarry, Elaine, The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Segovia, Fernando F., ‘Jesus as Victim of State Terror: A Critical Reflection Twenty Years Later’, in Crucifixion, State Terror, and Sexual Abuse: Text and Context, ed. David Tombs, Dunedin: Centre for Theology and Public Issues, University of Otago, 2018; http://hdl.handle.net/10523/8558.

Sloyan, Gerard S., The Crucifixion of Jesus: History, Myth, Faith, Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1995.

Tombs, David, ‘Crucifixion, State Terror, and Sexual Abuse’, Union Seminary Quarterly Review 53:1–2 (1999), pp. 89–109.

–––, ‘Prisoner Abuse: From Abu Ghraib to The Passion of The Christ’, in Religion and the Politics of Peace and Conflict, eds Linda Hogan and Dylan Lee Lehrke, Princeton, NJ: Princeton Theological Monograph Series, 2009, pp. 179–205.

–––, ‘Silent No More: Sexual Violence in Conflict as a Challenge to the Worldwide Church’, Acta Theologica 34:2 (December 2014), pp. 142–60.

–––, ‘Crucificação e abuso sexual’, Estudos Teológicos 59:1 (July 2019), pp. 119–32.

Trexler, Richard, Sex and Conquest: Gendered Violence, Political Order, and the European Conquest of the Americas, Cambridge: Polity Press, 1995.

United Nations Commission on Truth for El Salvador, From Madness to Hope: The Twelve Years War in El Salvador: Report of the Commission on Truth for El Salvador, 1992–93, New York: United Nations, 1993.

Notes

1 This chapter is an abridged version of David Tombs, ‘Crucifixion, State Terror, and Sexual Abuse’, Union Seminary Quarterly Review, 53:1–2 (Autumn 1999), pp. 89–109. The central argument was first presented as David Tombs, ‘Biblical Interpretation in Latin America: Crucifixion, State Terror, and Sexual Abuse’ in the Biblical Hermeneutics Section at the Society of Biblical Literature International Conference, 20 July 1998, Krakow, Poland. An abridgement was first published in Portuguese as David Tombs, ‘Crucificação e abuso sexual’, Estudos Teológicos 59:1 (July 2019), pp. 119–32, and republished as Crucifixion and Sexual Abuse (Dunedin: Centre for Theology and Public Issues, University of Otago, 2019), http://hdl.handle.net/10523/9834 (English); http://hdl.handle.net/10523/9843 (Spanish); http://hdl.handle.net/10523/9846 (French); http://hdl.handle.net/10523/9924 (German). This chapter version includes a few further minor amendments to the 2019 versions but the text is primarily intended to summarize the 1999 article rather than to reflect further developments since then. I hope to address further developments in David Tombs, The Crucifixion of Jesus: Torture, Sexual Abuse, and the Scandal of the Cross (London: Routledge, forthcoming).

2 See Fernando F. Segovia, ‘Jesus as Victim of State Terror: A Critical Reflection Twenty Years Later’, in David Tombs, Crucifixion, State Terror, and Sexual Abuse: Text and Context (Dunedin: Centre for Theology and Public Issues, University of Otago, 2018); http://hdl.handle.net/10523/8558.

3 For one of the most sophisticated and sustained developments of a contextual hermeneutic, see Clodovis Boff, Theology and Praxis: Epistemological Foundations (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1987). Boff’s approach recognizes both the similarities and differences between the contemporary Latin American context and the biblical world.

4 David Tombs, ‘Silent No More: Sexual Violence in Conflict as a Challenge to the Worldwide Church’, Acta Theologica 34:2 (2014), pp. 142–60.

5 On state terror and sexual abuses in Latin American torture in the 1970s and 1980s, see further discussion in Tombs, Crucifixion, State Terror, and Sexual Abuse. On reading crucifixion in the light of the torture at Abu Ghraib, see David Tombs, ‘Prisoner Abuse: From Abu Ghraib to The Passion of The Christ’, in Religions and the Politics of Peace and Conflict, eds Linda Hogan and Dylan Lee Lehrke (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Theological Monograph Series, 2009), pp. 179–205.

6 These include: Archdiocese of Sao Paulo, Torture in Brazil: A Report by the Archdiocese of São Paulo (New York: Vintage Books, 1986); National Commission on Disappeared People, Nunca Más: A Report by Argentina’s National Commission on Disappeared People (Boston, MA, and London: Faber and Faber, 1986); National Commission on Truth and Reconciliation, Report of the Chilean National Commission on Truth and Reconciliation (Notre Dame, IN: Centre for Civil and Human Rights, Notre Dame Law School, 1993); United Nations Commission on Truth for El Salvador, From Madness to Hope: The Twelve Years War in El Salvador: Report of the Commission on Truth for El Salvador, 1992–93 (New York: United Nations, 1993).

7 See the collection of essays that explore this from different disciplines in Juan E. Corradi, Patricia W. Fagen and Manuel A. Garretón, eds, Fear at the Edge: State Terror and Resistance in Latin America (Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 1992). On the use of torture to promote terror, see Elaine Scarry, The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985).

8 For a brief history of crucifixion, see the classic work by Martin Hengel, Crucifixion in the Ancient World and the Folly of the Cross (Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press; London: SCM Press, 1977).

9 Crucifixion was rarely used against Roman citizens and even these infrequent occasions were to punish lower classes rather than the aristocracy. On the use of crucifixion by the Romans, see the classic work by Hengel, Crucifixion. For recent treatments, see Raymond E. Brown, Death of the Messiah (New York: Doubleday, 1994), pp. 945–52, and the exhaustive bibliography, pp. 885–7; Stephen D. Moore, God’s Gym: Divine Male Bodies of the Bible (New York: Routledge, 1996); and Gerard S. Sloyan, The Crucifixion of Jesus: History, Myth, Faith (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1995).

10 The English translation, Josephus, The Jewish War, trans., G. A. Willon, revised edn (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1970) is used here and for all other passages cited below.

11 Analysis of how crucifixion was used in the ancient world is complicated by the close relationship between crucifixion, impalement and the hanging of bodies (which might be carried out either before or after death). That the New Testament writers can move easily between crucifixion and hanging on a tree is shown in Galatians 3.13; Acts 5.30; 10.39.

12 During crucifixion it is likely that all control over many body functions would have failed. The following account of electric shock torture in Argentina by Nélson Eduardo Dean suggests how humiliating the consequences of this would be: ‘During the application of electricity, one would lose all control over one’s senses, such torture provoking permanent vomiting, almost constant defecation, etc.’ National Commission of Disappeared People, Nunca Más, p. 39.

13 Further examples are included in Tombs, Crucifixion, State Terror, and Sexual Abuse.

14 ‘[H]e was tortured naked, after taking a bath, while hanging on the parrot’s perch where he received electric shocks from a magneto [small electric generator] to his genital organs and over his whole body.’ Quoting José Milton Ferreira de Almeida in Archdiocese of Sao Paulo, Torture in Brazil, p. 17.

15 On the sexualized use of the picana and other sexual aspects in Argentinean torture, see Francisco Graziano, Divine Violence: Spectacle, Psychosexuality, and Radical Christianity in the Argentine ‘Dirty War’ (Boulder, CO, and Oxford: Westview Press, 1992), especially pp. 153–8.

16 The rape of women during torture has been well documented but recorded instances of the rape of men are less frequent. The frequency with which male prisoners were subjected to some form of rape is hard to determine. However, it is clear that rape was sometimes used to torture men as well as women. Dr Norberto Liwski, whose extended testimony starts the Nunca Más report, describes his treatment in detail: ‘Another day they took me out of my cell and, despite my [previously tortured] swollen testicles, placed me face-down again. They tied me up and raped me slowly and deliberately by introducing a metal object into my anus. They then passed an electric current through the object. I cannot describe how everything inside me felt as though it were on fire.’ Quoting Dr Liwski in Nunca Más, p. 24.

17 1 Samuel suggests that emasculation and sexual assault were also recognized practices at an earlier time in Israel’s history. On emasculation, see 1 Samuel 18.27: ‘David rose and went along with his men, and killed one hundred of the Philistines; and David brought their foreskins, which were given in full number to the king, that he might become the king’s son-in-law.’ On the fear of sexual assault, see 1 Samuel 31.4: ‘Then Saul said to his armour-bearer, “Draw your sword and thrust me through me with it, so that these uncircumcised may not come and thrust me through, and make sport of me”.’ I am grateful to John Jarick for pointing these out to me.

18 Josephus, War, V. 452 (see above); Seneca, To Marcia on Consolation 20:3, records: ‘I see crosses there, not just of one kind but fashioned in many ways: some have their victims with head down toward the ground; some impale their private parts; others stretch out their arms on their crossbeam.’ Cited in Hengel, Crucifixion, p. 25.

19 Although Mark 15.15, Matthew 27.26 and John 19.1 are not explicit on this (and Luke does not mention a flogging), the sequence of events they describe strongly suggests it. Mark and Mathew (who have the flogging at the end of the trial) and John (who has the flogging midway through the trial) each report that immediately after the flogging Jesus was handed over to the Roman soldiers to mock him. All three present the first act of mockery as the soldiers dressing Jesus in a crown of thorns and a purple cloak (Mark 15.17), purple robe (John 19.2) or scarlet cloak (Matt. 27.28). There is no mention in Mark of needing to strip Jesus before dressing him, but stripping Jesus is explicitly stated in Matthew 27.28. Both Mark 15.20 and Matthew 27.31 also explicitly mention that after the mocking Jesus is stripped of the garb and his own clothes are put back on him for the procession to Golgotha. Brown notes that the usual custom outside Palestine was for the condemned man to be paraded naked to execution but that exceptions to this in Palestine may have been a concession to Jewish scruples on public nakedness (see Brown, Death of the Messiah, p. 870). It is possible that this sensitivity was especially high within the limits of the holy city.

20 This is clearest in John 19.23–24, which records that after putting Jesus on the cross the soldiers took his clothes to divide among themselves and that these included his undergarment for which they cast lots so as not to tear it. The Synoptic Gospels (Mark 15.24, Matt. 27.35 and Luke 23.34) are vaguer and simply refer to the division of his clothes by lots. In a careful assessment of the evidence Raymond Brown offers cautious support for the likelihood of full nakedness. Although Brown reports that the evangelists are not specific on the matter, and that they might not have known for sure, he offers three reasons that would support the view that Jesus was fully naked. Brown, Death of the Messiah, pp. 952–3.

21 On the deliberate humiliation of enemies by genital exposure, see 2 Samuel 10.4–5 which describes how David’s envoys were seized by Ha’nun and sent back with their beards half shaved and their garments cut off ‘in the middle at their hips’. Jewish sensitivity over insulting displays of the body is also shown in a disaster which occurred during the time that Cumanus was governor (48–52 CE). Josephus reports that a soldier on guard on the Temple colonnade during the Feast of Unleavened Bread lifted his tunic, bent over indecently and exposed himself to the crowds below while making indecent noises (War II. 223–7). Fearing a riot in the commotion that followed, Cumanus sent for heavy infantry but this triggered a panic, and Josephus claims that 30,000 were crushed to death as they tried to escape.

22 For Mark and Matthew this happens at the end of the trial and both mention it taking place in the praetorium. For John the mockery takes place during the trial and it appears to have been done within Pilate’s headquarters (John 18.28).

23 Luke places the mocking of Jesus rather earlier in the story at a point that is unlikely to have involved Roman soldiers. According to Luke 22.63–64, the mockery takes place prior to the trial before the Jewish elders. The mocking, beating, blindfolding and challenges to prophesy (Luke makes no mention of spitting) were carried out by the men who were holding Jesus overnight before the trial before the Council. Presumably these were members of ‘the crowd’ mentioned as capturing him in Luke 22.47. Mark 14.65 and Matthew 26.67–68 also report that Jesus was spat at, struck and challenged to prophesy, but they put this immediately after the Council had condemned him, rather than before, and say it was carried out by members of the Council themselves. John does not mention any parallel treatment associated with the questioning by the High Priest (John 18.19–24).

24 In addition, Matthew 27.29 also mentions placing the reed in Jesus’ right hand prior to striking him. Although John makes no mention of a reed, John 19.3 records Jesus being struck.

25 This chapter is primarily concerned with how the texts present events. The picture of abuse they present is historically very plausible but further assessment of textual historicity will not be attempted here. In view of the shame and embarrassment that would have been associated with sexual abuse, it is probable that the Gospels understate it rather than exaggerate it.

26 The privacy of the praetorium (whether Pilate’s palace or the Antonia fortress) means that the details of what transpired inside are inevitably circumstantial and would probably not have been known even at the time. Furthermore, even if it was believed that Jesus had been sexually assaulted in the praetorium, the absence of this in the Gospel accounts is hardly surprising. Apart from the distance of years and the desire to pass over a shameful event, the Gospels are usually seen as notably biased in excusing the Romans for Jesus’ trial and death.

27 Despite the attempts of the Gospels to excuse Pilate from blame, if rape did take place in the praetorium presumably it would only have done so with Pilate’s positive approval or knowing indifference. It is quite possible that Pilate deliberately handed Jesus over to be sexually assaulted by his soldiers as part of the crucifixion sentence. Such an action might have served to reinforce his own status as a triumphant lord who was able to sexually vanquish his victims through the actions of his underlings. Richard Trexler notes that a Roman master might find it more insulting to have his slaves rape his adulterous wife’s young suitor rather than to rape the youth himself. Richard Trexler, Sex and Conquest: Gendered Violence, Political Order, and the European Conquest of the Americas (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1995), p. 22.

28 Josephus (War, II. 268) suggests that, at least while Felix was procurator (52–60 CE), the majority of the Roman garrison in Caesarea were raised in Syria and they readily sided with the Syrian inhabitants of Caesarea in a civil dispute against its Jewish citizens.

29 Gorgias, 473C, cited in Sloyan, The Crucifixion of Jesus, p. 16.

30 Trexler, Sex and Conquest, p. 20. According to Trexler, ‘in the Ancient Greek world … the premier sign of male dependence was to be anally or orally penetrated by another male without, at least fictively, being able to resist’, p. 33; he continues, ‘Seneca … declared that “bad army officers and wicked tyrants are the main sources of rapes of young men”’, p. 34. In this context even the widely held assumption that the soldiers forced Jesus to wear scarlet/purple clothing for solely political mockery might be reconsidered. Dressing a male victim in bright clothing might also have been a prelude to sexual assault. See also Trexler, Sex and Conquest, p. 34.

31 This might also have implications for the question of why Judas had profound feelings of regret and repentance for his actions (Luke 22.3–5; Matt. 27.3–5). Judas may not have anticipated the full implications of his betrayal and if the argument here is correct his despair and shame would be easy to understand.