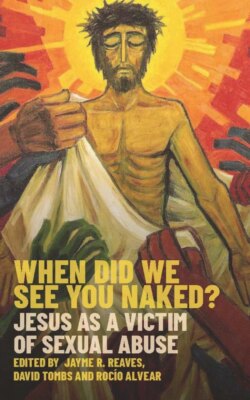

Читать книгу When Did we See You Naked? - Группа авторов - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2. Covering Up Sexual Abuse: An Ecclesial Tendency from the Earliest Years of the Jesus Movement?

MICHAEL TRAINOR

Australia’s Royal Commission into the Sexual Abuse of Minors and Vulnerable Adults uncovered one of the consistent and shocking tendencies of leaders of religious and church communities.1 This was the tendency to ‘cover up’.2 In order to prevent any scandal being focused on the Church, leaders sought to obfuscate the problem by moving perpetrators from one religious community to another, by blaming the one abused or by acting as though nothing was amiss and it was business as usual. This tendency was supported by an ecclesiology that regarded the Church as a ‘perfect society’ and its ministers as set apart through ordination, as unaccountable, and as acting in God’s name without transparency.3 Any flaws in the Church through human weakness could always be forgiven. This was applied to those who acted inappropriately and sinfully. At the heart of this ecclesiology, ministerial protectionism and cover-up, expressed through unaccountable conduct towards children, lies the culture of clericalism. The Commission summarizes this as:

the idealization of the priesthood, and by extension, the idealization of the Catholic Church. Clericalism is linked to a sense of entitlement, superiority and exclusion, and abuse of power.4

The ‘cover-up’ tendency as a product of clericalism is not a phenomenon of recent history. This chapter will demonstrate that it occurred among members of the Jesus movement in the first century CE. What follows falls into three parts.

First, we shall see how the story of Jesus in Mark’s Gospel, written around 70 CE, was a story about one who was protective of children and, like them, subject to maltreatment and abuse.5 Mark’s final story (Mark 14—16), anticipated by the disciples’ attitude to children and the verbal contestation between Jesus and his opponents, as well as Jesus’ own passion and death, becomes a story of sexual abuse with Jesus executed naked and ultimately shamed.6

Second, in Luke’s Gospel we see a different portrait. Luke presents Jesus as more majestic and dignified. Its author redacts Mark’s scene of the disciples’ response to children coming to Jesus (Luke 18.15–17), presents him as the victor in any verbal contest, and alters – almost removing entirely – the abusive treatment of Jesus found in Mark’s passion narrative. Instead of naked and shamed, the evangelist has Jesus die elegantly clothed.7

In the concluding section, I suggest the reasons for the alterations that Luke makes to Mark. The study will invite us – contemporary disciples concerned about the present situation that confronts our churches – to a spirit of openness, reflecting critically on the endemic that has plagued Jesus’ followers from earliest years, and to act, in so far as we are able, on behalf of those who are abused as we continue to explore ways of ministerial accountability and transparency.

Mark’s Gospel

Mark’s Gospel offers a portrait of Jesus that would speak into a Jesus household chronologically distant and culturally different from the world of the Galilean Jesus.8 Mark portrays Jesus as misunderstood and, as the story unfolds, someone who is gradually abandoned even by those closest to him. The ultimate moment of the sense of Jesus’ abandonment comes in his death scream of dereliction, ‘My God, My God, why have you abandoned me?’ (Mark 15.34). This is a highpoint in Mark’s Christological portrait, especially in what frames it – the lead-up to the death moment (Mark 15.21–33) and the centurion’s declaration that comes immediately after Jesus’ death (Mark 15.39), a point to which we shall return shortly.

Mark’s Gospel begins in the wilderness with John the Baptist’s teaching; from the wilderness Jesus appears calling his listeners to ‘repent’. Jesus’ first words in Mark are: ‘The time is fulfilled and the reign of God has drawn near. Repent and believe in the Good News’ (Mark 1.15).

The injunction, ‘repent’ (metanoeō), is more than a declaration to the disciples and all gospel listeners of a conviction of God’s presence and moral living. It is a call to a fundamental openness of heart to what is about to unfold in Jesus’ ministry. Metanoia is an invitation to perceive what is happening from a different point of view. As Mark shapes the narrative with a view to the final chapters, we remember the often-quoted words of Martin Kähler, who declared that the Gospels are ‘passion narratives with a lengthy introduction’.9 Mark’s ‘lengthy introduction’ reveals Jesus alone and misunderstood as antagonism begins in Mark 3 and heightens as the narrative moves forward, reaching its crescendo in the Gospel’s final chapters. All the time, the injunction metanoeō remains.

The Gospel auditor must listen beneath the surface of what happens to Jesus, at a second, deeper level that places the story against the backdrop of Mark’s cultural and historical situation. The evangelist writes not with a desire to freeze the memory of the Galilean Jesus in time and place, but, instead, with the intention of expanding the faith insights for a later Greco-Roman Jesus movement that the Gospel addresses, shaping its Christology to address the realia of Mark’s audience.

And what is that realia?

Mark’s Christological portrait offers a window into the situation of the Gospel’s audience. The way the evangelist portrays Jesus speaks into the situations that Mark’s householders face. One of these is sexual abuse. This emerges in the passion narrative, but it is subtly anticipated in the Gospel’s preceding chapters. There are, among many others, two indicators that flag or prepare the Gospel audience for the abusive treatment that Jesus will receive: the way the ‘little ones’ are treated by Jesus’ disciples, and the verbal interchange between Jesus and his antagonists. This intensifies as the story nears the Gospel’s denouement.

The ‘children’ in Mark’s Gospel

In the beginning of the second half of the Gospel, as Jesus begins to journey towards Jerusalem with his reluctant disciples, he sets a child (paidion) into the midst of his posturing entourage (Mark 9.36). He encourages a change of attitude, a metanoia, to receive the child, the quintessential symbol of social nothingness, into their midst.10 Their reception of the child becomes the touchstone of their openness to God (Mark 9.37). Not many verses later (Mark 9.42), Jesus reiterates his teaching about the protection of these ‘little ones’. It is evident, though, that the disciples have yet to absorb this message and have a different attitude to these ‘little ones’.

As some bring children (paidion) for Jesus to touch (Mark 10.13–16), the disciples ‘rebuke them’ (Mark 10.13b). Mark’s language here is revealing. The ‘rebuke’ (epitemaō) is the language of exorcism.11 The disciples see the presence of something or someone evil in a request that needs to be exorcised. They ‘rebuke them’. To whom is the disciples’ rebuke directed? Is it directed to those who bring the children to Jesus, or is it the children themselves? It seems the latter. Mark notes how Jesus reacts with indignation at the disciples’ belligerent response to the request (Mark 10.14). He instructs them to let the children come to him, ‘for to such belongs the kingdom of God’. The scene ends with Jesus wrapping the children in his arms and laying his hands upon them (Mark 10.16). The disciples need to undergo a radical metanoia if they are to receive and enter God’s kingdom (Mark 10.15).

The arrogance of the disciples or, to use an anachronistic expression, their ‘clericalism’, permits them to see the children or their carers as demonic and therefore deserving of rejection. The disciples see themselves as ‘entitled’ to treat them abusively. If this is how Jesus’ own disciples treat the ‘little ones’, what awaits the one who welcomes them with open arms? Mark prepares the auditor for this through the verbal exchange that takes place between Jesus and his adversaries. As the Gospel unfolds, the interchange directed at Jesus becomes more abusive until, finally, in the last chapters of the Gospel it reaches its expression that is more physical and sexual.12

The verbal interchange between Jesus and his opponents

From a cultural perspective, as the verbal disagreements and attacks on Jesus unfold, some interpret this as the classic verbal sparring of challenge and riposte.13 The overall intent, according to this interpretation, is an agonistic engagement intending to gain greater honour. The Gospel’s narrative audience to this engagement ‘gossip’ about Jesus, in a positive way, and speak well of him.14 There is a cyclical pattern in the interchange with Jesus’ antagonists: his honour is challenged; his critics are finally defeated; Jesus not only regains his honour but grows (through ‘gossip’) in the estimation of the audience who witness the contest; his antagonists are humiliated; their desire to kill Jesus only ferments more deeply.15 This pattern repeats in the chapters leading up to Mark’s passion narrative.

If we were to see a verbal contestation only in terms of a use of wit and who can outsmart the other, then we would miss an important element that anticipates Mark’s passion. In the ancient world, words were intended to be affective. Words influenced deeds and people’s actions.16 Speeches by the great orators were designed to win over the crowd and move it into some action or political response.17 Words were essential to garner support. Words of praise brought honour and glory to their addressee. Words of rejection and criticism were intended to dishonour, humiliate and spread negative gossip about the human target of the invective. Barbed words were intended to hurt, to impale their victims. Words had an impact that was both noetic and physical.

Mark’s passion narrative

In Mark’s passion narrative (Mark 14.1—16.8), the language addressed to and about Jesus by his antagonists reveals an intent to abuse him in a way that would have physical impact. His interrogators, first the religious authorities (Mark 14.53–65) and then Rome’s political leader (Mark 15.1–20), complete their verbal examination of Jesus with physical violence. This violence is also sexually implicit and shameful. It leads to the ultimate act of Jesus’ sexual humiliation in his death. The intent of the religious interrogation is clear: the authorities, the chief priests and the Sanhedrin, seek to discredit Jesus, to define his unholy scandal and so have reason to execute him (Mark 14.55). False testimony is called upon, but even this conflicts (Mark 14.56–60). The High Priest finally interrogates Jesus: ‘Are you the Christ, the Son of the Blessed?’ Jesus’ affirmation to this, with the addition ‘you will see the Human One seated at the right hand of Power and coming with the clouds of heaven’ (Mark 14.62), results in a charge of blasphemy that leads ultimately to his condemnation and a death sentence (Mark 14.64). Likewise, it also leads to the more explicit physical enactment of his humiliation preparatory for death. ‘And some began to spit on him and to cover his face, and to strike him, and say to him “Prophesy!” and the guards rained blows down on him’ (Mark 14.65).

Jesus’ face and head are the target of his bodily maltreatment. The ancient understanding of the human body adds further depth to the treatment that Jesus receives. Personal identity was linked to corporeality. The human body was more than a physical organ: it was a site of social identity and personhood. The body also linked the person to the wider cosmic and astral world, as borne out, for example, by Plato’s micro and macro cosmology. For Plato (427–328 BCE), the human and celestial bodies that compose the cosmos were linked.18 One influenced the other. Aristotle (384–322 BCE) had a similar regard for the human body as a social and cosmic map that mirrored the universe.19 From their limited anthropological perspectives Plato and Aristotle affirmed the symbolic and metaphoric nature of the human body in its relationship to society and the cosmos. If anything of this Greek philosophical tradition lies behind Mark’s story, then what happens to Jesus in his body has deep symbolic significance.

We know from an earlier story in Mark’s passion narrative (Mark 14.3–9) that when the unnamed woman anoints Jesus she anoints his head. Gospel auditors would see this act as reaffirmation of Jesus’ regal and prophetic status. The abusive treatment of Jesus’ head and face in Mark 14.65 brings together the two aspects of Jesus’ head and the prophecy made from the narrative’s anointing story. This act has implications for the members of the wider social world symbolized by Jesus’ head and, more specifically, Mark’s householders who identify with him. What happens to Jesus, their prophetic head, will also happen to them, if it is not already happening. Mark’s vignette shines a spotlight on the Gospel’s audience for what is happening, and will possibly happen, from Rome’s authorities. This is echoed in the second politically related interrogation before Rome’s representative, Pilate.

Pilate’s questioning of Jesus begins with the primary charge of treason or sedition: ‘Are you King of the Judeans?’20 This accusation about Jesus’ kingship continues throughout the interrogation. Mark portrays Pilate as indifferent to the charge brought against Jesus by the religious authorities. To placate the crowd growing in its hostility, he scourges Jesus and then hands him over to be crucified (Mark 15.15). The violent actions perpetrated by Pilate’s soldiers against Jesus add to Pilate’s initiating vicious deed. They perform a mock coronation ritual that ironically underscores Jesus’ regal status. The narrative’s chiastic structure makes the soldiers’ feigned attestation of royalty central (Figure 1).

The corporeal implications of the scene are unmistakable. Jesus is violated, maltreated, tortured, shamed and humiliated. The more demonstrable violence of this scene contrasts with the earlier humiliation from the religious authorities. The sexual innuendos of the scene are heightened. He is naked – this is the implication of B1 (Mark 15.20b) – covered only in a purple cloak. Even this is eventually ‘stripped’ from him. The violence in the way that the cloak is removed further underscores the intended mockery and humiliation of Jesus. The scene is one of sexual abuse. The act of humiliating Jesus’ physical being has sexual implications. Sexual humiliation will become more explicit in Mark’s scene of Jesus’ death.

The soldiers lead Jesus away to Golgotha for execution. Mark simply notes ‘they crucified him’ (Mark 15.24a), leaving all the pain and anguish suffered by the crucified victim to the imagination and memory of Mark’s audience. They would be well familiar with Rome’s crucifixion method. It is the next part of Mark’s statement that reminds Gospel auditors of the presumed nakedness of Jesus in this most humiliating moment and central story of the whole Gospel. The soldiers ‘divided his garments among them, casting lots for them, to decide what each should take’ (Mark 15.24b–c).

Mark presumes Jesus’ nakedness, as do the Gospel auditors. It is a high point of Mark’s story and a low point of humiliation and sexual shaming of the evangelist’s central figure. In this context Jesus dies alone, misunderstood and experiencing a sense of divine abandonment, though retaining his faith in his God whom, despite everything, he names ‘My God’ (Mark 15.34). The centurion’s final words sum up the scene. They question the veracity of the one declared as God’s Son: ‘In truth, was this man God’s Son?’ (Mark 15.39). Even at the moment of death, Jesus’ identity remains obscured and undeclared.21 His humiliation continues.

Much could be written about the evangelist’s purpose in presenting such a Christological portrait – of a sexually abused, solitary and misunderstood figure, crying out to his God to comfort him. Perhaps it can be briefly stated, as mentioned earlier, that this speaks into the realia of Mark’s audience: their own experience of abuse, maltreatment, rejection, loneliness and isolation in a Roman urban context of the 70s CE. The apparent silence of God in a time when some might have experienced violent sexual abuse warranted such a portrait.

Luke’s Gospel

Living a generation after Mark and working initially with Mark’s narrative, the evangelist of Luke’s Gospel offers an altered Christological portrait. The purpose, similar to that of Mark, was to speak into the new realia of Luke’s Greco-Roman context experienced by a culturally diverse household of Jesus followers, located in a different time and place.22 Luke adds Jesus’ birth story to Mark’s beginning, redacts central narrative stories of Jesus’ healing activity, and develops on his teaching, especially in a ‘Sermon on the Plain’ (Luke 6.20–49). Luke also expands the centre of Mark’s Gospel with ten chapters of teaching (Luke 9.51—19.27) as Jesus and his disciples journey towards Jerusalem, to his passion and death. Martin Kähler’s statement that the Gospels are ‘passion narratives with a lengthy introduction’ is as pertinent to Luke as much as to Mark.23

Luke’s ‘lengthy introduction’ presents Jesus as the revealer of God’s reign in word and deed. He heals, speaks and teaches in a more exalted manner than in Mark’s Gospel. Luke presents an elevated or heightened Christology. Rather than Jesus’ first words that recognize the closeness of God’s reign and invite disciples to ‘repent’, as in Mark 1.5, Luke has a 12-year-old Jesus in the Temple instructing its very teachers (Luke 2.46). In response to his parents’ dilemma as they search for him, Jesus speaks for the first time in Luke’s Gospel: ‘Did you not know that I must be in the things of my Father?’ (Luke 2.49b, author’s translation).

How interpreters understand the ‘things’ of my Father varies, from ‘the house’ (NRSV) to ‘the affairs’ (NKJV) to ‘matters’.24 Whatever ‘the things’ might mean, Luke portrays the young Jesus with a deep abiding relationship to his God that expresses itself early in his life. Luke’s is a very mature Jesus, even though the evangelist states later that Jesus grew in wisdom and stature (Luke 2.40, 52).

The ‘infants’ in Luke’s Gospel

Luke’s Christological portrait of Jesus as a child sheds light on the evangelist’s alteration to Mark’s equivalent scene in which people bring children to Jesus for him to touch (Luke 18.15–17). There are two noteworthy features to Luke’s episode.

First, in Luke, those brought to Jesus are called brephos, a change from Mark’s paidion. It is Luke’s favoured term.25 Brephos refers to an infant, even a child before birth, and therefore a creature significantly much younger and physically more immature and fragile than Mark’s paidion.26 The political and cultural status of the brephos deepens the fragility and social exclusion of the infant implied in Mark’s paidion. Jesus’ attitude to them in Luke would highlight his compassion and outreach to the most insignificant of society – a theme consistent throughout the Gospel.

The second feature in Luke’s story is the response of the disciples to these infants. If there is any ambiguity in Mark, Luke retains Mark’s ‘rebuke’ language, but it is solely directed to those bringing the brephos to Jesus. Jesus is not indignant at his disciples, as in Mark, but simply instructs with the same teaching found in Mark, reverting to the language of paidion: ‘whoever does not receive the kingdom of God like a child (paidion) will never enter it’ (Luke 18.17). Luke’s Jesus has no need to repeat this teaching. His disciples get it. They do not act with the same intense aggression as in Mark. Overall, Luke presents Jesus as welcoming the more socially fragile of society and the disciples as more receptive to those coming to Jesus. In a sense, Luke’s ‘cover-up’ of Mark begins here.

The conviction of Jesus’ communion with God articulated in Jesus’ earliest boyhood years is repeated in his first words expressed as an adult. In his threefold temptation (Luke 4.1–13), Jesus counters Satan’s refrain (‘If you are God’s son’) testing Jesus’ fidelity to God with words drawn from Deuteronomy (Deut. 8.3; 6.13, 16; 10.20). Jesus’ communion with his God is solid and unwavering.

The next words of Luke’s Jesus that follow are his programmatic declaration in the Nazareth synagogue (Luke 4.16–22). This outlines for Gospel auditors how his mission will unfold in the rest of the Gospel. Drawing on Isaiah, Jesus declares that he has come to bring release, healing and empowerment to the oppressed, captives and sightless. His mission is to reveal a God of hospitality to all who experience social and economic rejection. This insight lays out the primary criterion for a disciple that follows on from Jesus’ mission: disciples are invited to be witnesses of God’s hospitality and to enact it.

What for Mark is metanoia becomes for Luke hospitality.27 This expresses the nature of the God to whom Jesus witnesses as well as the foundational characteristic of the Lucan household. We have already seen something of this in Luke’s scene of Jesus welcoming the brephos. In a Greco-Roman world structured along hierarchical lines of economic and political convenience, a hospitable household characterized by friendship transcended socially defined boundaries. To outsiders, such a household could be interpreted as subversive. Luke’s agenda is to appeal to the wealthy members of the Jesus movement, a theme that suffuses the Gospel.28 The evangelist’s appeal shapes the Gospel’s elevated Christology and Jesus’ teaching on wealth and material ascetism. This agenda also explains the changed perspectives from Mark found in the Gospel as Luke’s construction of the Gospel’s portrait of Jesus emphasizes his dignity, cultural elegance and amicability. This further emerges in his interaction with his opponents.

Jesus’ interchange with his opponents

Luke’s Jesus is incontestably without peer. This Christology appears in episodes in Luke where Jesus contests the opposition he experiences. The evangelist draws on and reshapes Mark’s equivalent scenes.29 A closer examination of these reveals Luke’s tendency to tone down the challenge–riposte cyclical strategy of agonistic contestation from the Gospel’s Marcan source. Three examples illustrate this.

First, when Jesus reads and interprets Isaiah in the Nazareth synagogue to establish Luke’s Christology for the rest of the Gospel (Luke 4.16–30), the reaction is initially overwhelmingly positive: ‘All speak well of him and wondered at his gracious words’ (Luke 4.22). Only after his reinterpretation of the biblical tradition in terms of God’s hospitality and inclusivity of non-Jews does the tone of Jesus’ reception change (Luke 4.28–29). In Mark’s equivalent scene (Mark 6.1–6), there is no favourable disposition towards Jesus at all. It is heavily negative. His hearers take offence at him from the beginning (Mark 6.3). Mark concludes with the judgement on Jesus’ audience: he ‘marvelled because of their unbelief’ (Mark 6.6).30

Second, Mark’s story of Jesus’ healing of a man with a withered hand (Mark 3.1–6) ends with a plan between religious and royal officials to ‘destroy’ (apollumi) Jesus. In Luke’s equivalent scene (Luke 6.6–11), this authoritarian coalition is absent. Rather, his observers are filled with annoyance and ‘discussed with one another what they might do to Jesus’ (Luke 6.11). Mark’s plot to ‘destroy’ Jesus is absent, replaced by a consultation about some unspecified action against him. His destruction, though available to Luke from Mark’s Gospel, is played down by his detractors. Their response, though negatively intentioned, is more benign than in Mark.

Third, on the Temple Mount Jesus meets his theological opponents. They try again to test his allegiance to God and his attitude to Roman taxation. In Mark (Mark 12.13–17) an explicit alliance of religious and royal officials tries to ‘entrap him in his talk’ (Mark 12.13b). At the end of the attempted entrapment they are left in a state of amazement (Mark 12.17c). In Luke (Luke 20.20–26) the coalition of officials is absent. Unwilling to confront Jesus directly, they delegate spies to record what he says. At the end of the encounter, Luke notes their inability to catch him out. Instead, their amazement is heightened, and they are reduced to silence: ‘And they were not able in the presence of the people to trap him by what he said; and being amazed by his answers, they became silent’ (Luke 20.26).

The verbal interchange between Jesus and his opponents is significantly reduced in Luke’s Gospel. Jesus is the authoritative and unquestionable teacher and prophet. This Christological impression continues into Luke’s passion narrative (Luke 22.1—24.53) as the evangelist also significantly softens, if not changes, Mark’s portrait of the abused, misunderstood and abandoned Jesus.

Luke’s passion narrative

The Lucan evangelist follows Mark’s basic narrative of Jesus’ suffering and death, but with noteworthy differences. First, Mark’s story of the unnamed woman’s prophetic and regal anointing of Jesus’ head (Mark 14.3–9) occurs earlier in Luke’s Gospel (Luke 7.36–50). Here it is a story of a sinner who anoints and washes Jesus’ feet with oil and tears and becomes a lesson on forgiveness. Luke has moved it away from an action focused on Jesus that reaffirms his identity to an episode earlier in the Gospel (Luke 7.36–50) in which Jesus acts and offers moral instruction. Here, Jesus is not the subject, as in Mark, but the agent. Second, Luke adds a faction fight into the Last Supper scene (Luke 22.24–27) and converts Mark’s Gethsemane scene of a struggling and soul-wrenched Jesus (Mark 14.32–38) into a prayer event in which Jesus calmly faces death comforted by God’s angelic presence (Luke 22.39–46). In Mark’s scene, Judas identifies Jesus to his captors with a kiss (Mark 14.45), and that act of intimacy becomes an act of betrayal. In Luke, Judas draws near to Jesus to kiss him (Luke 22.47), but there is no actual kiss. Instead, a violent act by one of Jesus’ disciples that removes the ear of a high priest’s slave with a sword becomes a moment of healing as Jesus touches the slave’s ear and heals him (Luke 22.50–51).

Luke’s alterations to Mark intensify Jesus’ agency, his authority and apparent imperviousness to suffering. As Raymond Brown notes, Luke portrays Jesus as ‘more reverential … and avoids making him seem emotional, harsh or weak’.31 Elsewhere, Brown adds, ‘The resistance to portraying [Luke’s] Jesus as suffering during the passion befits a Hellenistic resistance to portraying emotions.’32 Luke’s Jesus is not the target of physical violence or verbal abuse as in Mark. This is evident in the trial scenes and their aftermath. In Mark, physical and sexual violence enacted against Jesus follow his religious and political trials. In Luke, this is either toned down or absent altogether.

The violence associated with Jesus’ trial by the council of Jerusalem’s religious leaders occurs in both Mark (Mark 14.65) and Luke (Luke 22.63–65) (Figure 2). In Luke it comes before the council, which allows for the auditor’s focus to fall on the main Christological titles of the trial. Jesus is the Christ (Luke 22.67), the Son of Man (Luke 22.69a), and the Son of God (Luke 22.70) who exercises God’s authority (Luke 22.69b). With Mark, the violence perpetrated against Jesus concludes a more prolonged and dramatic trial. Noteworthy is Luke’s redaction of Mark’s scene in which Jesus is maltreated:

| Mark 14.65 | Luke 22.63–65 |

| Some began to spit on him, to blindfold him, and to strike him, saying to him, ‘Prophesy!’ The guards also took him over and beat him. | Now the men who were holding Jesus began to mock him and beat him; they also blindfolded him and kept asking him, ‘Prophesy! Who is it that struck you?’ They kept heaping many other insults on him. |

Figure 2. Jesus’ mockery at his religious trial

In Mark’s scene, Jesus is spat upon, struck while blindfolded and beaten a second time by the guards. Luke also has Jesus derided, but he is held, mocked and beaten only once. Though Jesus is blindfolded and beaten, Luke does not use Mark’s more aggressive expression for ‘striking’. Jesus is not struck – even though he is asked who struck him. With this derisory, repetitive questioning, as those holding him ‘keep asking him’, Luke explicates and underscores the prophetic nature of Jesus. It is a Christological theme in his Gospel.33 In Luke the mention of Jesus’ beating occurs only at the beginning of the scene. There is no other violent action. Physical violence from Mark’s scene is replaced with verbal abuse in Luke, as ‘they kept heaping many other insults on him’ (Luke 22.65). Verbal abuse continues into the next two scenes (Luke 23.1–24), but they are otherwise devoid of physical violence.

When Luke switches to Jesus’ civic trial before Pilate (Luke 23.1–5), the same emphasis from Mark – Jesus’ royal status – is again the focus, though with the added accusation of his capacity to pervert the nation and refusal to pay taxes to Caesar (Luke 23.2). In other words, Jesus is a royal pretender and a threat to the Roman Empire. What is clear is Pilate’s declaration of Jesus’ innocence (Luke 23.4), which he twice repeats (Luke 23.14–15, 22) after the intervening trial before Herod. This second trial before Pilate (Luke 23.6–16) places Jesus in the presence of Herod, who had longed to see Jesus having heard so much about him.

Herod unsuccessfully questions Jesus as the religious leaders further accuse him ‘vehemently’ (Luke 24.10b). There is one final action that Herod performs after he and his soldiers mock Jesus with contempt (Luke 23.11): he places a luminescent, shining or resplendent (lampros) garment around Jesus.34 For Luke’s audience, its symbolism is unmistakable. Jesus reveals and reflects the radiance of God before Rome’s authoritative figure. The garment echoes Jesus’ dazzlingly radiant raiment on the mountain as he becomes transfigured (Luke 9.29). His authoritative presence as God’s revealer remains even in the face of mockery from Rome’s emblematic authority. Moreover, this luminous garment remains on Jesus throughout the rest of Luke’s passion narrative. It is never taken off and accompanies him to the cross and grave. As Jesus is handed back to Pilate (Luke 23.13–23) and finally over for crucifixion (Luke 23.24–25), Luke completely omits any ironic royal investiture and mock coronation ritual as seen in Mark. Luke’s Jesus is above such physical violence and abuse. His status demands better treatment.

Luke’s description of a less violent and abusive treatment of Jesus continues as the Gospel moves towards the moment of his crucifixion and death. He journeys to the place of execution accompanied by a great multitude, the women of Jerusalem and two criminals to be executed with him (Luke 24.26–33). Luke converts Mark’s scene of Jesus’ misunderstanding, ultimate loneliness and abandonment at the moment of death into one that displays forgiveness and prayerful communion with God. His death becomes an example of prayer: he utters the words, ‘Father, into your hands I commit my spirit’ as he dies (Luke 23.46). In keeping with Luke’s portrait of Jesus’ regal and honoured status, the luminous garment placed earlier around him by Herod is not removed. Jesus does not die naked as in Mark but covered. A synoptic comparison (Figure 3) between the two Gospels at the mention of what the guards do about Jesus’ garments at the point of his crucifixion bears this out:

| Mark 15.22–24 | Luke 23.33–34 |

| And they brought him to the place of Golgotha which means place of a skull, and they offered him wine mixed with myrrh, he did not take it. And they crucified him and, dividing his clothes, they cast lots for them to decide what each should take. | And when they came to the place which is called ‘Skull’ There they crucified him, and the criminals, one on his right and one on his left. And Jesus said, ‘Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing’. They cast lots to divide his garments. |

Figure 3. The Division of Jesus’ Clothing

The way that Mark describes the division of Jesus’ garments and the lot-casting for them by the guards presumes that the clothing is no longer on Jesus. They are described as having divided his clothing already. He is naked, as would have been the custom in the Roman execution method.

Luke, on the other hand, has the guards cast lots in order to divide Jesus’ garments. There is no indication that Jesus is without them or that he is naked. At this moment of the Gospel’s highpoint, Luke synthesizes a Christological portrait of Jesus forgiving his executioners, promising Paradise to a repentant thief, prayerfully offering himself into the hands of God and preserving his dignity in death. The luminous garment from Herod remains. Luke literally covers up Mark’s naked Jesus.

Conclusion

Luke’s Jesus is an authoritative preacher whose ultimately incontestable words place him within the Greek philosophical tradition of wisdom. The Gospel’s portrait intends to appeal to those of elite social status within the Lucan household. This results in a radical modification of Mark’s portrait of an abused, misunderstood and lonely figure. Luke’s Jesus is a more exalted figure appealing to the gentle and refined sensibilities of the Gospel’s primary – though not exclusive – audience.35 He welcomes the most fragile creatures of human society, the brephos. In Luke’s Gospel, the disciples’ response to those who bring them to Jesus is toned down from Mark. Unlike in Mark, the disciples in Luke understand Jesus’ instruction about having the attitude of the child in order to welcome the kingdom. Further, Luke moderates the verbal and physical violence done to Jesus in Mark’s Gospel. Any depiction of the sexual abuse of Luke’s dignified and majestic figure is inappropriate and ‘covered up’.

Luke’s redacted Christology has softened, if not removed, the figure of an abused, lonely and misunderstood Jesus from the contemplative gaze of the Gospel’s audience. Luke clothes Mark’s naked Jesus with a luminous garment given to him by Herod, Rome’s representative. This accompanies him in death, in a scene that converts Mark’s screaming, abandoned, naked figure into one of peaceful, serene and prayerful dignity. No mention is made of the garment’s removal. It appears that it remains on Jesus as he is laid in the tomb and added to by the explicitly mentioned ‘linen’ cloth in which Joseph finally shrouds the body of Jesus (Luke 23.53). The Herodian garment and the linen shroud symbolizing eternity are the residual images in the Gospel’s passion narrative that communicate Luke’s Christology of Jesus’ regal and heavenly status.

Luke’s tendency to ‘cover up’ and dignify Jesus has mixed consequences. On the one hand, the evangelist offers a portrait of Jesus that would appeal to an elite audience far removed from the artisan and peasant world of the historical Jesus. The teachings of the Galilean Jesus offer Luke a way of socially reconstructing the Gospel household in terms of hospitality and friendship. On the other hand, Luke’s ‘cover-up’ also pushes the issue of societal abuse and sexual oppression – dominant in Luke’s world and a mechanism of control, especially within the Greco-Roman domestic scene – into the background.36

Whatever the reason for Luke’s redactional predisposition to ‘cover up’ Mark’s Christological portrait, it reflects a tendency that has continued in the Jesus movement ever since. This is the inclination in ecclesial circles to conceal the truth and camouflage what is embarrassing, unpalatable and scandalous. Luke’s reformulation of Mark’s graphic and confronting portrait of a violated and sexually abused Jesus seeks to screen the Gospel audience from the reality of criminal execution in the Roman world. Rather, a more dignified figure emerges whose agenda is not to scandalize but affirm.

This is not to say that Mark’s Christology is better or more honest than Luke’s. Rather, the exercise of comparing Luke’s Gospel presentation of Jesus with that of Mark highlights the human inclination to paper over what is scandalous and confronting. Whatever the reason for Luke’s alteration of Mark’s portrait of the suffering and dying Jesus – whether to offer a palatable Christology for Luke’s more genteel audience or to reduce any possibility of scandal that Mark’s portrait might produce – the evangelist’s redaction of Mark does give us pause for thought, especially in the light of the present ecclesial situation in Australia. The Gospels are ‘windows’ and ‘mirrors’.37 They offer us a window into the social and cultural world in which they were written. They also reflect back to their readers/listeners insights and a hermeneutic pertinent for the realia of today’s Gospel audience. From the context in which I write, this study invites me to reflect again on the situation which the Australian Catholic Church faces and the scandal caused through the sexual abuse of minors and vulnerable adults within my ecclesial community. It took the work of a Royal Commission over years to allow the ‘mirror’ to expose what had been happening in the Church and to honour the stories of those who had been abused. The bishops and other faith leaders in the Australian Catholic Church have been called to account for what has happened historically and to put in place systems of transparency and accountability. What Luke has done to Mark – again, for whatever reason – mirrors what this leadership has also done. But in the present situation, we know the reasons for the cover-up: to avoid scandal, to protect the institution, to deflect responsibility, evade accountability and reinforce clericalism. A conspiracy of silence has accompanied this tragic situation within the Church. This ‘cover-up’ has been exposed. Its exposure now invites a move towards a more open, humble and transparent Church that welcomes the child – the Gospel’s theological metaphor for the estranged, abused and hurt.

References

Adamczewski, Bartosz, The Gospel of Luke: A Hypertextual Commentary, European Studies in Theology, Philosophy and History of Religions, Frankfurt: Peter Lang GmbH, 2016.

Anthony, Peter, ‘What are They Saying about Luke–Acts?’, Scripture Bulletin 40 (2010), pp. 10–21.

Aristotle, Politics, 1, 2; 5, 2; De Anima 2, 1f.

Berry, D. H., and Andrew Erskine, Form and Function in Roman Oratory, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Briggs, Richard, Word in Action: Speech Act Theory and Biblical Interpretation – Toward a Theory of Self-Involvement, Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2001.

Brown, Colin, ed., The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology, vol. 1, Exeter: The Paternoster Press, 1975, pp. 280–91.

Brown, Raymond E., An Introduction to the New Testament, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1987.

–––, An Introduction to the New Testament: The Abridged Edition, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016.

Brown, Raymond E., and John P. Meier, Antioch and Rome: New Testament Cradles of Catholic Christianity, New York: Paulist Press, 1983.

Byrne, Brendan, A Costly Freedom: A Theological Reading of Mark’s Gospel, Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 2008, pp. ix–21.

Daniels, John W. Jr, ‘Gossip in the New Testament’, Biblical Theology Bulletin 42 (2012), pp. 204–13.

Deacy, Susan, and Karen F. Pierce, eds, Rape in Antiquity: Sexual Violence in the Greek and Roman Worlds, London: Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd, 2002.

Donahue, John R., ‘Windows and Mirrors: The Setting of Mark’s Gospel’, The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 57:1 (1995), pp. 1–26.

Donahue, John R., and Daniel Harrington, The Gospel of Mark, Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2002.

Ernst, Josef, Das Evangelium nach Markus, Regensburg: Pustet Verlag, 1998.

Faggioli, Massimo, ‘Australia’s Findings on Clerical Sexual Abuse: A Report with Ramifications’, La Croix International, 22 December 2017, https://international.la-croix.com/news/australia-s-findings-on-clerical-sex-abuse-a-report-with-ramifications/6628.

Gadenz, Pablo T., The Gospel of Luke, Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2016.

Guelich, Robert A., Mark 1–8:26, Dallas, TX: World Publishing, 1989.

Harrington, Daniel, The Gospel of Matthew, Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1991.

Hengel, Martin, Studies in the Gospel of Mark, Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 1985.

Hooker, Morna, ‘Trials and Tribulations in Mark XIII’, Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester 65 (1982), pp. 78–99.

–––, Gospel According to St. Mark, London: A & C Black, 1991.

Kähler, Martin, ‘[D]ie Evangelien Passionsgeschichten mit ausführlicher Einleitung nennen’, in Der sogennante historische Jesus und der geschichtliche, biblische Christus, 2nd edn, Leipzig: A. Deichert, 1896.

Karris, Robert J., ‘Windows and Mirrors: Literary Criticism and Luke’s Sitz Im Leben’, Society of Biblical Literature 1995 Seminar Papers, 115 (1979), pp. 47–58.

Kelber, Werner H., Mark’s Story of Jesus, Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 1979.

Levine, Amy-Jill, and Ben Witherington, The Gospel of Luke, New Cambridge Bible Commentary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Moloney, Francis, The Gospel of Mark: A Commentary, Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2002.

Neyrey, Jerome, ‘The Absence of Jesus’ Emotions – the Lucan Redaction of Lk 22, 39–46’, Biblica 61 (1980), pp. 153–71.

Oerke, Albrecht, ‘λάμπω’ in Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, eds Gerhard Kittel and Gerhard Friedrich, vol. 4, Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1964, pp. 16–28.

Plato, Timaeus 90 a, b.

Rohrbaugh, Richard L., ‘Honor: Core Value in the Biblical World’, in Understanding the Social World of the New Testament, eds Dietmar Neufeld and Richard E. DeMaris, New York: Routledge, 2009, pp. 125–41.

Royal Commission into Institutional Responses into Child Sexual Abuse, Final Report, 2017, www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/.

Searle, John R., Ferenc Kiefer and Manfred Bierwisch, eds, Speech Act Theory and Pragmatics, Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Company, 1980.

Severino Croatto, Jose, ‘Jesus, Prophet Like Elijah, and Prophet-teacher Like Moses in Luke-Acts’, Journal of Biblical Literature 124 (2005), pp. 451–65.

Struthers Malbon, Elizabeth, Mark’s Jesus: Characterization as Narrative Christology, Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2009.

Trainor, Michael, About Earth’s Child: An Ecological Listening to the Gospel of Luke, Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2012.

–––, The Body of Jesus and Sexual Abuse: How the Gospel Passion Narratives Inform a Pastoral Response, Northcote: Morning Star Publications, 2014.

Whitaker, Robyn, ‘Rebuke or Recall? Rethinking the Role of Peter in Mark’s Gospel’, The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 75 (2013), pp. 666–82.

Notes

1 Royal Commission into Institutional Responses into Child Sexual Abuse, Final Report, 2017, www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/.

2 This, among other things, is summarized in vol. 16 of the Royal Commission’s findings, Final Report, at www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/religious-institutions.

3 For a summary of this tendency, see the analysis of the Commission’s findings and its implications for the Australian Catholic Church by Massimo Faggioli, ‘Australia’s Findings on Clerical Sexual Abuse: A Report with Ramifications’, La Croix International, 22 December 2017, https://international.la-croix.com/news/australia-s-findings-on-clerical-sex-abuse-a-report-with-ramifications/6628.

4 Royal Commission, Final Report: Religious Institutions, vol. 16, book 1, p. 43, www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/final_report_-_volume_16_religious_institutions_book_1.pdf.

5 For a helpful summary of the design, presumed social context and worldview behind Mark’s Gospel, see Brendan Byrne, A Costly Freedom: A Theological Reading of Mark’s Gospel (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 2008), pp. ix–21.

6 This is explored in Michael Trainor, The Body of Jesus and Sexual Abuse: How the Gospel Passion Narratives Inform a Pastoral Response (Northcote: Morning Star Publications, 2014), pp. 93–124.

7 For a full study of Mark’s Christology, consult Elizabeth Struthers Malbon, Mark’s Jesus: Characterization as Narrative Christology (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2009).

8 Those who received Mark’s Gospel were possibly resident in one of the great urban Roman centres, perhaps even Rome itself, around the 70s CE. For those who posit Rome as the setting for Mark, see, for example, Josef Ernst, Das Evangelium nach Markus (Regensburg: Pustet Verlag, 1998), pp. 112–14; Martin Hengel, Studies in the Gospel of Mark (Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 1985), pp. 1–30; Raymond E. Brown and John P. Meier, Antioch and Rome: New Testament Cradles of Catholic Christianity (New York: Paulist Press, 1983), pp. 191–7; Robert A. Guelich, Mark 1—8:26 (Dallas, TX: World Publishing, 1989), pp. xxix–xxxi; Morna Hooker, ‘Trials and Tribulations in Mark XIII’, Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester 65 (1982), pp. 78–99. A minority posit a rural audience, not too distant from Jesus’ context in ancient Palestine/Israel. Francis Moloney conjectures Mark’s location as ‘somewhere in southern Syria’ and dates it after 70 CE but before 75 CE, in The Gospel of Mark: A Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2002), p. 11. Morna Hooker later sums up the scholarship on Mark’s provenance: ‘All we can say with certainty, therefore, is that the Gospel was composed somewhere in the Roman Empire – a conclusion that scarcely narrows the field at all!’; Hooker, Gospel According to St. Mark (London: A & C Black, 1991), p. 8. Whatever the provenance of the Gospel, the Greco-Roman cultural context shapes the Gospel narrative and the author’s portrait of Jesus to enable this to speak into the realia of the Jesus movement in a context different from Galilee.

9 ‘[D]ie Evangelien Passionsgeschichten mit ausführlicher Einleitung nennen’ in Martin Kähler, Der sogennante historische Jesus und der geschichtliche, biblische Christus, 2nd edn (Leipzig: A. Deichert, 1896), p. 51.

10 Daniel Harrington, The Gospel of Matthew (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1991), pp. 264–7.

11 Werner H. Kelber, Mark’s Story of Jesus (Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 1979), p. 48; Robyn Whitaker, ‘Rebuke or Recall? Rethinking the Role of Peter in Mark’s Gospel’, The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 75 (2013), p. 671. This is not the only time that Mark mentions epitemaō (also in Mark 1.25; 3.12; 4.39; 8.30; 9.25; 10.48).

12 Examples of Mark’s anticipation of the ultimate verbal–physical agonistic interchange that leads to Jesus’ passion and death are seen in Mark 2.1–12, 15–19; 3.1–6; 6.1–6; 7.1–22; 8.11–13; 10.2–9; 11.27–33; 12.12–27, 35–44.

13 Richard L. Rohrbaugh, ‘Honor: Core Value in the Biblical World’, in Understanding the Social World of the New Testament, eds Dietmar Neufeld and Richard E. DeMaris (New York: Routledge, 2009), pp. 125–41.

14 On ‘gossip’ in the ancient world, see John W. Daniels Jr, ‘Gossip in the New Testament’, Biblical Theology Bulletin 42 (2012), pp. 204–13.

15 Mark spells out the murderous intent of Jesus’ critics early in the Gospel, in Mark 3.6. This theme runs as an undercurrent through the remaining part of the Gospel narrative, reaching a climax in its final chapters.

16 On the nature of orality as speech-act, see, for example, Richard Briggs, Word in Action: Speech Act Theory and Biblical Interpretation: Toward a Theory of Self-Involvement (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2001); John R. Searle, Ferenc Kiefer and Manfred Bierwisch, eds, Speech Act Theory and Pragmatics (Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Company, 1980).

17 D. H. Berry and Andrew Erskine, Form and Function in Roman Oratory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), pp. 7–17.

18 Plato, Timaeus 90 a, b.

19 Aristotle, Politics, 1, 2; 5, 2; De Anima 2, 1f.

20 My translation here seeks to render Iudaioi as a regional rather than national identity.

21 This interpretation flies in the face of the conventional commentary on the centurion’s words as a high point of Christological identity, and now by a representative of Rome. Contra to this and for the position I take here, see Trainor, Body of Jesus, pp. 114–17.

22 For a helpful summary on the current state of Lucan scholarship, see Peter Anthony, ‘What are They Saying about Luke–Acts?’, Scripture Bulletin 40 (2010), pp. 10–21. Also see Amy-Jill Levine and Ben Witherington, The Gospel of Luke (New Cambridge Bible Commentary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), pp 1–17; Byrne, Hospitality of God, pp. 4–22.

23 ‘[D]ie Evangelien Passionsgeschichten mit ausführlicher Einleitung nennen’ in Kähler, Der sogennante historische Jesus und der geschichtliche, biblische Christus, p. 51.

24 Bartosz Adamczewski, The Gospel of Luke: A Hypertextual Commentary, European Studies in Theology, Philosophy and History of Religions (Frankfurt: Peter Lang GmbH, 2016), p. 65; Pablo T. Gadenz, The Gospel of Luke (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2016), p. 66.

25 Brephós occurs eight times in the NT, six of which are in Luke-Acts, including Luke 2.12, 16; Acts 7.19.

26 On the distinction between paidíon and brephós, see Colin Brown, ed., The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology, vol. 1 (Exeter: The Paternoster Press, 1975), pp. 280–91.

27 On the theme of Lucan hospitality, see Byrne, Hospitality of God, pp. 8–11.

28 On Luke’s appeal to the wealthy elite in the Gospel household, see Michael Trainor, About Earth’s Child: An Ecological Listening to the Gospel of Luke (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2012), pp. 7, 27–30.

29 The scenes that Luke draws on from Mark and redacts include Luke 5.17–26, 29–39; 4.16–30; 6.6–11; 20.20–40, 41–44.

30 For further on this change that Luke makes to Mark, see John Donahue and Daniel Harrington, The Gospel of Mark (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2002), p. 183; Byrne, Costly Freedom, p. 105.

31 Raymond E. Brown, An Introduction to the New Testament: The Abridged Edition (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016), p. 93.

32 Raymond E. Brown, An Introduction to the New Testament (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1987), p. 270. For further study on Jesus’ absence of emotion in Luke’s Christology, see Jerome Neyrey, ‘The Absence of Jesus’ Emotions – the Lucan Redaction of Lk 22, 39–46’, Biblica 61 (1980), pp. 153–71.

33 Jose Severino Croatto, ‘Jesus, Prophet Like Elijah, and Prophet-teacher Like Moses in Luke-Acts’, Journal of Biblical Literature 124 (2005), pp. 451–65.

34 Albrecht Oerke, ‘λάμπω’ in Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, eds Gerhard Kittel, and Gerhard Friedrich, vol. 4 (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1964), p. 17.

35 For a discussion on the social composition of Luke’s household and the elite as the primary addressees of the Gospel see Trainor, About Earth’s Child, pp. 26–39.

36 Susan Deacy and Karen F. Pierce, eds, Rape in Antiquity: Sexual Violence in the Greek and Roman Worlds (London: Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd, 2002).

37 The recognition of these metaphors (‘windows’ and ‘mirrors’) as descriptors for the Gospels was popular among interpreters in the late twentieth century. See, for example, Robert J. Karris, ‘Windows and Mirrors: Literary Criticism and Luke’s Sitz Im Leben’, Society of Biblical Literature 1995 Seminar Papers, 115 (1979), pp. 47–58; John R. Donahue, ‘Windows and Mirrors: The Setting of Mark’s Gospel’, The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 57:1 (1995), pp. 1–26.