Читать книгу When Did we See You Naked? - Группа авторов - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

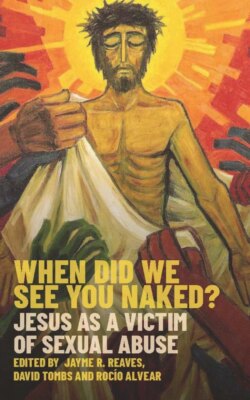

ОглавлениеIntroduction: Acknowledging Jesus as a Victim of Sexual Abuse

JAYME R. REAVES AND DAVID TOMBS

At the heart of this book is a surprising, even scandalous, claim: that Jesus was a victim of sexual abuse. It may seem a strange and implausible idea at first. This initial puzzlement is to be expected; the starting point and central focus of the book is both unusual and confronting. As the following chapters will highlight, there is significant evidence that, at the very least, the forced stripping and naked exposure of Jesus on the cross should be acknowledged as sexual abuse.1 The acknowledgement of this truth has the potential for positive consequences, but we also acknowledge it is a difficult and disturbing subject to address. Sexual abuse points to what is speakable – and what is unspeakable – in the suffering Jesus experienced.

To say that Jesus suffered, even suffered greatly, is uncontentious. Jesus’ suffering is firmly attested in Christian faith as we know it. The Apostles’ Creed explicitly acknowledges Jesus’ suffering with the phrase ‘suffered under Pontius Pilate’ (passus sub Pontio Pilato). The word excruciating (derived from the Latin crux) connects the cross (crux) with acute suffering in the passion narratives. The early Church at the Council of Chalcedon (451 CE) firmly condemned the Docetic heresy, which denied the reality of Jesus’ suffering. The ruling established that Christian orthodoxy included an acknowledgement of the reality of suffering on the cross.

A number of works have also spoken of Jesus’ suffering as torture.2 Naming Jesus’ ordeal as torture underlines the intentional cruelty and violence in his mistreatment. The term ‘torture’ is not used in the Gospel texts to describe Jesus’ experience. However, a close reading of the passion narratives provides a strong argument for seeing Jesus’ experience in this way. Although some might prefer not to use the word ‘torture’ for Jesus’ experience, there are few Christians likely to see the use of the term as morally shocking or theologically objectionable. To acknowledge Jesus’ suffering as torture does not create new theological difficulties.

To acknowledge Jesus as a victim of sexual abuse, however, typically prompts a very different reaction: blank surprise, stony silence, scepticism, correction, or even offence. Some ask questions like, ‘Do you really mean that?’ Others say there is no evidence in the Bible to support such a claim. Some flatly declare, ‘You can’t say this.’ Jesus is readily spoken of as a victim of suffering, and there is little problem in describing his suffering as torture. But to speak of him as a victim of sexual abuse is shocking and meets resistance. Why? We have come to see the resistance to the idea of Jesus as a victim of sexual abuse as part of the key to understanding what sexual abuse means and why it could be so important to our understanding of both Jesus’ experience and our contemporary context.

If our experiences over years of work with church and academic groups are an indication, there are often several stages that people go through as they consider this proposal. At first, it is likely to be viewed as speculative conjecture, without biblical or historical evidence to support it. Or it might be seen as a subjective reading imposed on the text and drawing on an agenda from a very different time and place, rather than being supported by the text itself. Why, people may ask, if Jesus suffered sexual abuse, has this not been recognized in 2,000 years of Christian history? If it were in the Bible, they may continue, surely it would have been more openly acknowledged before now? This stage is marked by a sense of the novelty of the claim, and the lack of familiarity with the biblical evidence that supports it.

Deeper dynamics are also often at work. The resistance to this suggestion also takes the form that it is absurd, insulting, offensive, and even blasphemous. Those who oppose it claim that it conflicts with both the historical record and the theological understanding of who Jesus was. The chapters in Part 1 of this volume will show that evidence of the sexual abuse of Jesus is clear in the biblical text but is rarely noticed or discussed. The failure to notice this abuse in the Gospel texts is linked to how the texts are usually read.3 Some chapters in this volume mention the limited scholarship in this area, and it is important to register both this silence and the reasons for it at the outset. The paucity of work on Jesus and any sexual topics makes an open discussion on Jesus and sexual abuse very difficult.

It is hardly surprising, then, that the suggestion that Jesus should be acknowledged as a victim of sexual abuse at first seems to be absurd. When most people think of the crucifixion, they think of visual representations in Christian art, often explicitly regulated by the Church. For example, the final session of the Council of Trent (1545–1563) set down requirements on holiness and devotion in religious art. The Council’s 25th Decree stipulated that ‘all lasciviousness be avoided’ and nothing be seen that is disorderly or unbecoming.4 Although the convention of a loincloth was already established in practice, this ruling explicitly increased the pressure to conform to such conventions, with those who flouted it at risk of being declared anathema. As a result, there are few visual images which illustrate the reality of Jesus’ naked exposure. The number started to increase in the twentieth century, but these are still a small minority. In the common visual imagination of crucifixion, both in churches and in wider society, a modest loincloth obscures the clear historical record of the nature of crucifixion.

Despite the fact that a fully naked Jesus is only rarely depicted, the historical reality is nonetheless quite widely known. Historians and biblical scholars believe that Jesus was fully naked on the cross even though it is rarely discussed in detail. Similarly, many churchgoers are familiar with this reality and so describing Jesus as naked on the cross is not new.

Over the years, our experience has been that it is the naming of the stripping and nakedness as sexual abuse that is new to people, rather than the nakedness itself. And it is here that we come to a strange mismatch between what we know and what we acknowledge. It seems it is possible to know about the nakedness of Jesus on the cross, and even see this depicted in some artistic works, and yet still not describe or name his stripping and forced naked exposure as sexual abuse. This reticence becomes more obvious if we contrast it with contemporary examples of prisoners who have been stripped naked in detention, such as, for example, the prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib in Iraq in the early 2000s.5 There was no reticence in the wide coverage of this scandal or in describing the stripped and humiliated detainees at Abu Ghraib prison as victims of sexual abuse. Indeed, it was so obvious that a reluctance to describe it in such a way would be seen as dishonest.

Some have suggested that Jesus suffered abuse, but that stripping and exposure are not really sexual. This raises questions about when abuse should be recognized or qualified as sexual abuse. To believe that the more generic term of ‘abuse’ (instead of ‘sexual abuse’) would be preferable is problematic. What sort of abuse is stripping and forced exposure if it is not sexual abuse? Public stripping, enforced nakedness and sexual humiliation constitute sexual abuse because they are attacks on sexual identity and sexual vulnerability. They have a specifically sexual meaning. They derive their power and impact because they were understood – and still are understood – to have a sexual dimension. To name them only as abuse is to mischaracterize what has happened, which serves to distort the reality of Jesus’ experience.

When the initial surprise has passed, many people find it difficult to understand why it has taken them so long to see what is obvious, something that seems, in fact, to have been hidden in plain sight. They ask questions about what might have prevented them from seeing this before, and they often wonder why it is never mentioned in sermons. These questions should be taken seriously. Unspoken reasons behind the reluctance to notice and name Jesus’ experience as sexual abuse need to be recognized. Deeper conversations on the subject often reveal that assumptions about stigma are a critical factor in people’s attitudes. Most frequently, the resistance comes from the sense that Jesus would be somehow demeaned and less worthy as a saviour if he were a victim of sexual abuse.

The stigma and shame that comes with being named as a victim of sexual abuse is one of the central concerns that we want to identify and explore in this volume. The early Church spoke of the immense shame Jesus endured in his trial, torture and execution. Indeed, in this light the profound shame may be the key to the offence and scandal of the cross acknowledged by the apostle Paul in 1 Corinthians 1.23. However, over the centuries the memory of this shame has been lost. Despite the display of so many images of Jesus’ body hanging from a cross, we are unable to see what is right in front of us. When it is named in ways that make the shame and humiliation more explicit, this naming is often resisted.

We see the resistance to the idea as at least as important as the idea itself. It is because of the resistance that we as editors felt it important to put this collection together. A question articulated by a respondent to a recent presentation captured this issue succinctly: ‘If it is acceptable to say that Jesus suffered torture and crucifixion, why is it not acceptable to say that he was the victim of sexual abuse as well?’6

There are several levels to this discussion: what happened, why people resist this idea, and why these both matter. The issues are closely linked to the importance of acknowledging that Jesus was a victim of sexual abuse. We believe that appropriately exploring these painful and difficult issues can lead to positive consequences for survivors of abuse, those who love them, for the Church as the body of Christ, and for the wider society in which silence about sexual violence has been accepted as the norm. We hope to provoke a longer-term conversation.

A starting point for this volume is the work by David Tombs from over 20 years ago. In his 1999 article ‘Crucifixion, State Terror, and Sexual Abuse’, Tombs drew on Latin American liberationist hermeneutics for a reading of biblical texts with attention to both past and present contexts.7 He described the dynamics of state terror and sexual abuse in the torture practices of the regimes of Brazil, Chile, Argentina, Guatemala and El Salvador in the 1970s and 1980s. He then used this historical reality as a vantage point from which to re-examine Roman crucifixion practices that might shed light on the biblical narratives. A guiding hermeneutical principle was that those reports on torture provided a lens through which to see the first-century context and the biblical text in new ways.

Understanding the use of torture for state terror – and the prevalence of sexual abuse in torture practices – provides insights into what is clearly present within the texts but is often unrecognized or ignored. Torture reports also raise the possibility of further sexual assault that may have taken place in the praetorium. Since this article was first published in 1999, reports from Sri Lanka, Libya, Syria, Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, Myanmar and other contexts have attested to a range of sexual abuses being a feature of the mistreatment of prisoners in detention and a global issue.

Tombs’ article focused primarily on a historical rereading and the hermeneutical approach that might support this. However, in a short final section it offered a brief reflection on some of the theological and pastoral implications of this recognition prompted by the parable of judgement (Matt. 25.31–46). Matthew 25.40 provides a clear theological basis for affirming that Christ shares in the suffering of others: ‘Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me.’8

We have taken the words ‘When did we see you naked?’ (Matt. 25.38–40) from the parable as the title for this book. The parable of judgement does not suggest that Jesus was himself naked, nor did he need to be for his teaching to convey his message. However, the words capture a question that needs to be asked. Later, in Matthew 27, as the passion story unfolds, this question, ‘When did we see you naked?’ becomes more urgent and immediately relevant. The book title is intended to raise the question as to whether we see the naked Jesus in Matthew 27 and other texts or avoid what is in front of us. It is an invitation to reflect back during the passion narratives to the question asked in Matthew 25.38–40 with a new awareness of what was actually done to Jesus and a new sense of what he might fully share with others.

In this book we explore both Jesus’ historical experience of sexual abuse and the theological and pastoral significance that this might have today. We are not saying that sexual abuse is the only form of suffering that Jesus experienced in his trial, torture and execution. It is not our intention to limit understandings of Jesus’ crucifixion in any way. Instead, our aim is to broaden the established narrative and to notice the gaps in the story that have heretofore been untold and/or unacknowledged.

Sexual violence and sexual abuse have been a part of lived experience for millennia, and its presence is shockingly prevalent in the biblical text as well. Nevertheless, one of the prevailing characteristics of sexual violence is that it can be hidden in plain sight. Either by commission or omission, it is often unseen and rarely discussed outside of specialist scholarship or within victim/survivor support groups. Often we need a catalyst – something outside the norm of what we think and how we do things – to push us to see something differently and to give us new ways of knowing. In recent years, revelations of clergy sexual abuse and sexual harassment cover-ups, and the corresponding #MeToo and #ChurchToo movements, have shone light into some of the most shame-filled experiences of society. As much as ever, we need theologies and biblical interpretations that offer tools that address issues related to sexual violence and abuse in a way that can lead to liberation rather than continued stigma, silence and despair.

The chapters in this book take up the questions and challenges of understanding Jesus’ experience in a way that may at first seem unimaginable. What is presented here is not intended to shock. It is offered with a serious historical, theological and pastoral concern. Many contributors write not just as scholars but as people deeply committed to the Church in a variety of ways. They write with an awareness that the topic is sensitive. Breaking the silence around the unspeakable is fraught with risk of offence. However, keeping silent involves risk of a different sort. As Sara Ahmed says, ‘Silence about violence is violence.’9 Silence risks acceptance of the status quo and complicity with how things are. Sexual abuse and sexual violence demand a response beyond silence. As survivors and people who work with them attest, breaking silence can be a first step to transformation.

How to discuss Jesus as victim of sexual abuse is a question that has to be opened up, not a provocation that must be closed down. But of course this raises ethical concerns. As Roxane Gay asks: ‘How do you write violence authentically without making it exploitative? … [W]e need to be vigilant not only in what we say but also in how we express ourselves.’10 The question is not whether unspeakable abuse should or should not be addressed, but how it can be addressed in an appropriate way.

Here, authors take a number of theological approaches: feminist, womanist and post-colonial hermeneutics; discourse analysis; constructive and practical theology; memoir and reflection; poetry; and qualitative research drawing on victim/survivor testimony and faith community response. These chapters reflect a variety of opinions and starting points. There is a range of emotions also at play within these pages: curiosity, pain, hope, rage, courage, disgust, healing, anger, as well as resolve to create a better world. For some, there is hope and redemption to be found in the acknowledgement of Jesus as a victim of sexual abuse, and in the belief that recognition of shared experience has value and meaning. For others, there is more attention to the pain and the harm, including a charge to the reader that there are no easy answers.

The work is divided up into four main sections. We are grateful for the authors’ insights and their courageous commitment in this volume to build a framework for our exploration.

Part 1: Biblical and Textual Studies introduces the topic with an exploration of the biblical text and historical sources related to Jesus’ crucifixion. This part starts with an abbreviated version of David Tombs’ 1999 article, entitled here ‘Crucifixion and Sexual Abuse’. The original article is now readily available and offers greater detail on the politics of ‘state terror’, exploring the torture practices of the Roman Empire in comparison to Latin American regimes in the 1970s and 1980s. The chapter included here focuses on connections between sexual violence and torture and gives perspective on the sexual humiliation, violence and abuse involved in crucifixion.

Michael Trainor’s chapter, ‘Covering Up Sexual Abuse: An Ecclesial Tendency from the Earliest Years of the Jesus Movement?’, provides a comparative analysis of the passion accounts in Mark and Luke. Trainor takes into account narrative choices made in each Gospel that reflect early Church sensibilities and what the Gospel audience(s) would have heard and understood. Trainor’s work reads the gospel tradition in the light of the cover-ups conducted within the clergy sexual abuse scandals in Australia, drawing parallels between the two.

Mitzi J. Smith explores the crucifixion narratives in the Gospels from a womanist lens with her chapter ‘“He Never Said a Mumbalin’ Word”: A Womanist Perspective of Crucifixion, Sexual Violence and Sacralized Silence’. Smith explores the parallels in black hymnody, the reality of lynching and racialized sexual violence by building on the notable work of James Cone and Angela Sims, and considers how the black church in the US has historically made meaning from Jesus’ ‘silent suffering’ in New Testament accounts.

Monica Poole introduces three biblical texts in her chapter ‘Family Resemblance: Reading Post-Crucifixion Encounters as Community Responses to Sexual Violence’. Through a lens of feminist biblical studies, Poole takes on Thomas’s doubting demands (John 20.24–25), the centurion’s declaration of belief (Luke 23.46–49) and Jesus’ words ‘Don’t touch me’ (noli me tangere; John 20.17). In these three texts, Poole takes consent and believing victims/survivors of sexual violence seriously. She also compares acts of sexual violence to a bomb blast with wide area effects, arguing that the ‘blast radius’ includes not only the victim’s own trauma, but how the community members respond, including in ways that may compound the harm.

In Jeremy Punt’s chapter ‘Knowing Christ Crucified (1 Corinthians 2.2): Cross, Humiliation and Humility’, the focus shifts into the Pauline New Testament. Punt explores the concern for Jesus’ body in Pauline literature and Paul’s emphasis on the humiliation of the cross. In this chapter, Punt addresses gender, body, shame and honour, and what it meant for the church in Corinth to follow a shamed and crucified Christ.

In the final chapter in Part 1, there is a comparative analysis from Gerald O. West entitled ‘Jesus, Joseph, and Tamar Stripped: Trans-textual and Intertextual Resources for Engaging Sexual Violence Against Men’. West draws links between the Hebrew Bible and New Testament to illuminate sexual violence through forced stripping. He explores the Joseph narrative in Genesis 37—46, the Tamar narrative in 2 Samuel 13, and the gospel texts Mark 15 and Matthew 27. West also describes a contextual Bible study methodology developed at the Ujamaa Centre in South Africa to take this further. In this work, West and colleagues focus on contextual readings that consider the specific experience of men who have been victims of sexual violence and abuse.

Part 2: Stations of the Cross comprises 14 poems entitled ‘This is My A Body’ from Irish poet and theologian Pádraig Ó Tuama. These serve as a meditation on the 14 Stations of the Cross observed mainly within the Roman Catholic tradition. Ó Tuama’s wider work in the areas of peace, conflict, queerness, biblical studies, stories and the body provide a rich range of resources to encourage new thinking. The moving reflections presented here give space for a different type of creativity which, in turn, enables a different type of engagement with the material. The content of this volume is difficult and we hope to provide multiple entry points for engagement, from biblical studies into cultural analysis, and on to lived experience in the later chapters.

Part 3: Parsing Culture, Context and Perspectives starts with the chapter ‘Conceal to Reveal: Reflections on Sexual Violence and Theological Discourses in the African Caribbean’ by Carlton Turner. Turner uses post-colonial hermeneutics and socio-historical analysis in order to address the legacies of shame and the systemic consequences of sexual violence in the Caribbean that are ‘hidden in plain sight’. Looking specifically at the legacy of slavery and colonialism and then considering its effect on African Caribbean culture and dance hall music, Turner’s work connects these strands to build a painful picture of a violent past and present that still offers hope and scope for resistance and healing.

Rachel Starr invites us to consider culture via the television show Veronica Mars with her chapter ‘“Not pictured”: What Veronica Mars Can Teach Us About the Crucifixion’. Continuing a ‘hidden in plain sight’ theme, Starr uses storytelling and references in Veronica Mars and pop culture to explore bigger questions. She asks what exactly it is in the torture and sexual violence experienced by Jesus – if anything – that saves us. In true feminist fashion, Starr reads the gaps in the stories, considering who is left out, whose story is not told, and why.

In ‘Jesus is a Survivor: Sexual Violence and Stigma Within Faith Communities’, Elisabet le Roux builds upon qualitative research based on the lived experiences of survivors of sexual violence in various African countries undertaken by faith-based organizations. In this chapter, Le Roux considers the cultural contexts and perspectives that inform understandings and responses from individuals and faith communities that lead to stigmatization and pressure to conform and/or stay silent.

Ruard Ganzevoort, Srdjan Sremac and Teghu Wijaya Mulya creatively tweak the words of Matthew 25.40 in their title ‘Why Do We See Him Naked?: Politicized, Spiritualized and Sexualized Gazes at Violence’. They offer a critical perspective on the differing ways in which we see, understand and make meaning of sexual violence, and explore how this applies to Jesus’ crucifixion. Drawing on academic conversations between sadomasochism and Christian theology, they ask how the torture practices of the cross can be seen by a Christian audience as both sexual and spiritual.

In ‘The Crucified Christa: A Re-evaluation’, Nicola Slee critiques the representation of the abuse and humiliation of women in Christa figures and discusses how Christa figures might bring the nakedness, sexual humiliation and abuse of Jesus into clearer public view. From a feminist and practical theology perspective, Slee argues that the gendering of nakedness as female in Christian thought and representation may act as a further barrier to recognizing the significance of Jesus being naked on the cross.

Writing from Botswana, Mmapula Diana Kebaneilwe combines womanist theology and critical discourse analysis methodology in ‘Jesus as a Victim of Sexual Abuse: A Womanist Critical Discourse Analysis of the Crucifixion’. In this chapter, Kebaneilwe draws on the lived experiences of women in Botswana and explores how the stripping of women as an act of public sexual humiliation and abuse in Botswana can inform a reading of the stripping of Jesus and vice versa.

Finally, with Part 4: Sexual Abuse, Trauma and the Personal, we gather together stories and reactions from survivors and those close to them. They consider the legacy of sexual abuse and the ways in which victims, survivors and the ones who love them make meaning of the experience. They ask searching questions for which there are no easy answers.

The chapter from Beth R. Crisp entitled ‘Jesus: A Critical Companion in the Journey to Moving On From Sexual Abuse’ begins this final section. Crisp provides a personal victim/survivor account, considering the various tools and resources available within the Christian tradition and her personal faith that enabled her to reclaim her experience. She then explores issues related to communal responsibility and solidarity.

From the perspective of those who bore witness to Jesus’ abuse, Karen O’Donnell explores what bystanders and witnesses are called to do in her chapter ‘Surviving Trauma at the Foot of the Cross’. O’Donnell calls us to an ethical activism that is informed not just by solidarity, but also by bearing witness and embodying a love that prioritizes survival out from the depths of fragmentation and death, and into life. Moreover she also constructs and includes a liturgical resource based in the Church of England (Anglican) tradition that takes the needs of victims/survivors and their community to heart.

Shanell T. Smith writes a raw and powerful account entitled ‘“This is My Body”: A Womanist Reflection on Jesus’ Sexualized Trauma During His Crucifixion from a Survivor of Sexual Assault’. Smith is a womanist New Testament scholar and writes a personal reflection on the ongoing legacy and pain of sexual abuse and the questions that remain in relation to Jesus’ experience in the light of her own. This chapter reflects Smith’s 2020 publication touched: For Survivors of Sexual Assault Like Me Who Have Been Hurt by Church Folk and for Those Who Will Care.

The volume concludes with ‘Seeing His Innocence, I See My Innocence’, written by Rocío Figueroa and David Tombs, who are fellow co-editors for this volume. Their chapter reflects the findings from a qualitative research project with women who served in religious orders and were victims/survivors of clergy sexual abuse. Figueroa and Tombs present responses from several women as to what acknowledging Jesus as a victim of sexual abuse means for them and how helpful that acknowledgement may or may not be in relation to their own personal experience.

We have formatted the notes and referencing in a way that makes the scholarship as accessible as possible in order to facilitate further learning and research. Readers will note a diversity of sources. The work here is not limited to academic and biblical scholarship but also takes into account public sources such as news media, podcasts, TV series, poetry, fiction and other ‘everyday’ sources that help us make sense of what we encounter on a daily basis.

We believe that understanding Jesus as a victim of sexual abuse matters in ways that might not be obvious at first. This is partly because truth matters, and this truth has been hidden for too long. It is important to be honest in naming the things that over 2,000 years of Christian tradition have largely not been named. However, we believe that naming this truth does more than just correct a historical record about the past. It is a truth that matters in the present because it can make a practical difference. For the wider Church, it can help to expose and challenge the stigma that many in the churches mistakenly impose on survivors of abuse. Some survivors feel a personal sense of solidarity and practical support in seeing that Jesus experienced sexual abuse. Other survivors report that Jesus’ experience should be acknowledged as historical fact but they do not take comfort in this as survivors. They say the concern for practical consequence should be directed at the wider Church rather than being seen as a help to survivors. It is important to hear these different responses and understand the experiences behind them. Understanding Jesus as a victim of sexual abuse will mean different things to different people. Diverse voices need to be heard and we hope this volume will lead to a deeper understanding of Jesus’ experience and further conversation on how and why this experience matters.

Our hope is that with this volume the reader is challenged, encouraged and given tools to reconsider the story of the cross and what these reconsiderations mean not only for victims and survivors of sexual violence but also the Church as a whole. Ultimately, what makes this work distinctive and constructive is its commitment to testing whatever theological constructions and new forms of knowledge are made by setting them alongside the lived experiences of victims and survivors of sexual violence and abuse. The following chapters offer new opportunities to question assumptions in received traditions and to think anew about the passion story, and they provide new tools and reading practices that work toward liberation, justice, healing and life.

Notes

1 See also David Tombs, ‘Crucifixion, State Terror, and Sexual Abuse’, Union Seminary Quarterly Review 53:1–2 (Autumn 1999), pp. 89–109; Elaine A. Heath, We Were the Least of These: Reading the Bible with Survivors of Sexual Abuse (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos, 2011); Wil Gafney, ‘Crucifixion and Sexual Violence’, HuffPost, 28 March 2013, www.huffingtonpost.com/rev-wil-gafney-phd/crucifixion-and-sexual-violence_b_2965369.html; Michael Trainor, The Body of Jesus and Sexual Abuse: How the Gospel Passion Narrative Informs a Pastoral Approach (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2014); Chris Greenough, The Bible and Sexual Violence Against Men (London: Routledge, 2020).

2 See especially John Neafsey, Crucified People: The Suffering of the Tortured in Today’s World (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2014).

3 Indeed there has been very little serious discussion of the historical Jesus in relation to any form of sex and sexuality. Church traditions have sustained an association of sex with impurity, maintained a long-standing taboo around Jesus and sex, and implied Jesus had no sexuality. See William E. Phipps, The Sexuality of Jesus: Theological and Literary Perspectives (New York: Harper & Row, 1973); Leo Steinberg, The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion (New York: Pantheon Books, 1983); Robert Beckford, ‘Does Jesus have a Penis? Black Male Sexual Representation and Christology’, Theology & Sexuality 5 (1996), pp. 10–21.

4 The Canons and Decrees of the Sacred and Oecumenical Council of Trent, ed. and trans. J. Waterworth (London: Dolman, 1848), pp. 235–6.

5 Mark Danner, Torture and Truth: America, Abu Ghraib, and the War on Terror (New York: Review Books, 2004).

6 Jessica Delgado, ‘Response to Papers on Sexual Violence and Religion’, Joint Symposium of the Center of Theological Inquiry and Center for the Study of Religion, Princeton, NJ, 7 December 2018.

7 Tombs, ‘Crucifixion, State Terror, and Sexual Abuse’, pp. 89–109. See also Fernando F. Segovia, ‘Jesus as Victim of State Terror: A Critical Reflection Twenty Years Later’ in Crucifixion, State Terror, and Sexual Abuse: Text and Context, ed. David Tombs (Dunedin: Centre for Theology and Public Issues, University of Otago, 2018), http://hdl.handle.net/10523/8558.

8 Jayme R. Reaves and David Tombs, ‘#MeToo Jesus: Naming Jesus as a Victim of Sexual Abuse’, International Journal of Public Theology 13:4 (2019), pp. 387–412.

9 Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), pp. 260–1.

10 Roxanne Gay, Bad Feminist (New York: HarperCollins, 2014), p. 135.