Читать книгу The Tomb Chapel of Menna (TT 69) - Группа авторов - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

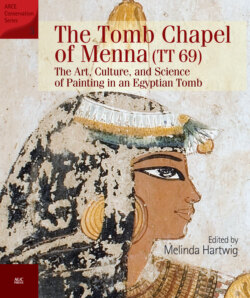

ОглавлениеIntroduction

The Significance of the Tomb Chapel of Menna (TT 69)

Melinda Hartwig

The tomb of Menna, Theban Tomb 69, is tucked into the hill of a necropolis popularly known as the Tombs of the Nobles in the ancient town of Thebes, now Luxor (Fig. 0.1). Named after the shrine of a local saint (Sheikh Abd al-Qurna, or Qurna for short) that sits at the top of the hill, it was the final resting place for many elite officials who served the kings from the ancient Egyptian Old Kingdom until the end of the pharaonic period. Among these burials, the tomb of Menna is one of the best-known due to the superb quality of its paintings. These paintings— among the finest ever created in ancient Egypt—reflect the elevated status of the tomb owner, Menna, as well as the creativity and skill of the ancient painters and the wealth of resources available to them. Given its fame, the tomb chapel of Menna was open for many years to visitors and exposed to environmental influences that led to slow disintegration of its decorated walls. The following chapters offer an in-depth look at the tomb of Menna using contemporary scientific methods of conservation and analysis situated within an art-historical and Egyptological framework, to give readers a view into one of the most beautiful and sophisticated of the ancient Egyptian painted tombs.

The contents of this book chronicle the results of the Tomb of Menna (TT 69) Project, a three-year project that was sponsored by Georgia State University and the American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE)’s Egyptian Antiquities Conservation Project (EAC) with funding from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). From 2007–2009, this project oversaw the conservation, scientific examination, and digital recording of the tomb chapel of Menna, with the goal of setting a new standard for the documentation and conservation of ancient Egyptian monuments. The primary goal of the project was to use minimally invasive analysis to conserve and document the painted decoration in the tomb chapel. Every component of the tomb was examined using a combination of state-of-the-art, portable, interdisciplinary techniques that did not require physical contact with the wall. Given the project’s focus on conservation and the non-invasive recording of the tomb, it was decided not to include excavation, but leave the possibility open for future generations. For this reason, the concrete floor in the tomb chapel was removed, leaving the original dirt ground. The results of the Tomb of Menna (TT 69) Project will be briefly summarized here, and covered in more depth in the following chapters.

Figure 0.1: External view of the tomb of Menna, Sheikh Abd al-Qurna.

Figure 0.2: Wall key of the tomb chapel of Menna (TT 69), Sheikh Abd al-Qurna.

This volume uses a reference system based on a common nomenclature or designation for each of the tomb chapel’s walls. This system organizes the walls along a central axis that moves from the outside forecourt, into the Broad Hall of the tomb chapel, and back into the Long Hall (Fig. 0.2). Beginning with the walls to the right and left of the entrance door (EDR and EDL, respectively), the Broad Hall is further divided according to whether the walls lie near or far from the entrance, such as Broad Hall Near Left (BHNL) or Broad Hall Far Right (BHFR). The walls at either side of the Broad Hall are identified as small walls, such as Broad Hall Small Left (BHSL). The inner-door walls are defined as left and right (IDL and IDR). In the long or inner hall, the walls are described in terms of right and left (LHR and LHL), or far (LHF) which is the statue shrine. The ceilings are referenced in terms of their placement in the Broad Hall (BHC) or Long Hall (LHC). Following standard epigraphic conventions, each column or row is identified in parentheses (1). Where the beginning of the text is not known, the columns or rows will be identified in terms of (x + 1), etc. If the text is destroyed, it is marked by … and reconstructions are noted by brackets [ ].

The two chapters in Part 1 examine Menna’s prosopogra-phy and the history of the tomb, its iconography, and texts. Chapter 1 discusses the previous work done in and around the tomb, the identity of Menna and his family, and the date of the tomb, which is based on the tomb chapel’s painting style, the use of specific types of scenes and texts, construction methods, and its overall placement within the necropolis. Also examined are the reasons for the expansion and repainting of the tomb chapel, visible on the BHNR wall. Chapter 2 surveys the scenes and texts found in Menna’s tomb chapel and their significance. Beginning with a short discussion of the function of Theban tombs, the tomb-chapel scenes are examined in terms of their placement, their cultural, historical, and religious significance, and their meaning in the overall decorative program. Methods of analysis range from epigraphic research (the study of the hieroglyphic inscriptions) to the identification, description, and interpretation of iconography (the content and meaning of the scenes).

Part 2 (chapters 3–6) presents the archaeometric methods, conservation, and documentation techniques that were utilized in the tomb chapel of Menna. Chapter 3 begins with the archaeometric procedures that were used to study the paintings in the tomb of Menna. Archaeometry is defined as the application of scientific devices and techniques from natural sciences to answer specific questions about different materials in the context of art history or archaeology.2 The archaeometric techniques used in the tomb chapel of Menna were energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence (XRF) combined with ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) and near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy and Raman spectroscopy (Raman): the former provided information on the morphology, chemical composition, and structure of the materials present, and the latter was introduced to refine and validate the exact chemical and organic properties of certain samples. All of these methods work with the effect of light. As the light interacts with the atoms of the painting sample, a small fraction of the scattered light is dispersed; the wavelength of light emitted is characteristic of an element or organic substance, and the intensity of light emitted is proportional to its concentration. Thus, these techniques did not require physical sampling that would harm the painting or its matrix. The readings obtained were employed to determine the state of conservation of the painting as well as the causes and mechanisms of its deterioration. They were also used to characterize objectively the artistic techniques and technologies, as well as the geographic origin of the materials and their date.

After millennia of exposure to the elements, not to mention the effects of dwellings built around the tomb, and tourists, the tomb chapel required a multifaceted conservation campaign. The group of conservators implemented a system to preserve as much of the original monument as possible, keeping intervention at a minimum, and, when it was necessary, using only traditional and compatible materials.3 The conservators also noted signs of earlier preservation attempts within the tomb chapel in their condition survey—which was digitized to provide a reference for later conservators, when and if it is deemed necessary to undertake another conservation campaign. The results of the two seasons of conservation in the tomb of Menna are summarized in chapter 4.

Chapter 5 documents the processes used for digital photography. Raking-light (severely angled hard light) photographs were taken of selected scenes to study the impasto of the paintings. Ultraviolet light photographs were shot in order to detect and identify particular pigments, coatings, or binding agents. So that the tomb decoration was recorded as precisely as possible, hundreds of high-resolution digital photographs were taken, which were then calibrated and stitched together to recreate the painted walls, resulting in some files as large as 1.9 gigabytes. A geometric method was devised and developed by Dr. Kai-Christian Bruhn from the University of Applied Sciences in Mainz, Germany, and implemented by photographer Katy Doyle, to produce stitched digital images of the tomb chapel walls that corresponded exactly to one plane. The goal was to create an exact replica of the walls and their decoration that could be printed for use by conservators to document the existing conditions, by archaeometrists to plot their points, and art historians to study the iconography, texts, and work process of the painting.

In Sheikh Abd al-Qurna, rock-cut tomb chapels are notorious for the instability of the indigenous rock, which necessitated the application of a painting ground composed of mud, hacked straw, and chips of limestone pressed onto a brittle and flaking rock face, over which several layers of gypsum plaster were applied. In the tomb chapel of Menna, marks of previous documentation efforts were commonly found, including pushpin holes, chalk marks, and sharp etched lines along figural outlines where paper had been hung and used to trace the images. To keep the integrity of the painted decoration, the outlines of both texts and images were traced from the abovementioned digital photographs as vector drawings, which produced exact and clear line drawings without touching the walls.

This photographic technology made possible the creation of a life-size replica of the tomb chapel decoration and texts, which was displayed at the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio during its exhibition “The Egyptian Experience: Secrets of the Tomb” (October 29, 2011–January 8, 2012).

As mentioned above, the paintings in the tomb chapel of Menna are known for their beauty, innovation, and sophistication, as well as their fine state of preservation. In fact, the entire decorative program is preserved almost in its entirety, which gives the researcher a rare opportunity to study the process by which the artists painted the tomb chapel. As explained in chapter 6, a new protocol of visual analysis was developed that examined each stage of the painting process from the preparation of the walls to the final coatings. The results of these painting stages were then joined with the archaeometric findings that identified the precise composition of the pigment mixtures. The coupling of these two techniques provided an objective assessment of the pictorial techniques used by the artists as well as their work process inside the tomb chapels.

Part 3 (chapter 7) presents the tomb of Menna in context. The chapter examines the overall nature of the paintings in the tomb of Menna and how they reflect the historical, religious, and cultural context of the time in which they were created. A number of details in the tomb chapel paintings point to cultural shifts and artistic changes occurring in Egypt that reveal an upwardly mobile, wealthy, and relatively powerful patron who sought to impress his peers or colleagues and document the various facets of his life, using some of the best painters of the day. The artists experimented with pigment mixtures, painting techniques, and unique vignettes, creating a visually stunning tomb chapel.

Through the extensive photographs and line drawings presented in this volume, the tomb chapel of Menna comes to life. The thoughtful conservation and scientific investigation allowed researchers to explore nearly every aspect of the tomb chapel and its decoration, and bring those results together here. It is hoped this volume will inspire a new generation of art historians, conservators, Egyptologists, and scientists to pursue multidisciplinary projects that strive to bring the strengths of each discipline to bear on the preservation and documentation of ancient Egyptian monuments, so that subsequent generations can be enriched and enjoy them long into the future.