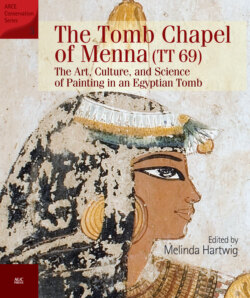

Читать книгу The Tomb Chapel of Menna (TT 69) - Группа авторов - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

The Tomb of Menna and Its Owner

Melinda Hartwig

Previous work, construction,and placement of the tomb

Cut into the cliffs or desert valley floor, Eighteenth Dynasty Theban tombs were composed of three levels: the upper level, or the chapel superstructure, which included the façade wall; a middle level composed of a walled forecourt leading to a rock-cut chapel; and a lower level made up of the subterranean burial complex. Each level served a purpose for the eternal life of the deceased: the upper façade related to his or her place within the celestial cycle, the middle-level chapel served as the site for the celebration of the tomb owner’s cult, and the lower-level tomb protected the owner’s body within the Osirian realm. Often the forecourt was sunk into the ground in order to gain the necessary height for the façade, and it was accessed by a ramp or stairway. Ideally, the forecourt was rectangular and opened to the east with the chapel façade to its west, creating a symbolic passage from the land of the living to the land of the dead in the ‘beautiful west.’ The façade was often crowned by a torus molding with a cavetto cornice and several rows of frieze cones set into the superstructure, each stamped with the name and titles of the deceased and his wife, as well as prayers and other dedications. Often, a niche was cut above the entrance to the chapel and housed a stelophorous statue of a kneeling man holding a stela inscribed with a hymn to the sun. The chapel was entered from the forecourt, through an entrance that was sometimes closed by a wooden door, which was easily opened for chapel ceremonies, celebrations, and other visits.

The lower-level burial complex was composed of one or more vertical shafts and/or sloping passages that were cut into the floor of the chapel or forecourt, each leading to single or multiple burial chambers below.1 The burial chamber held the coffin with the mummy and other funerary objects. Once the body and funerary goods were deposited in the burial chamber, the doorway was blocked by a wall of mud brick or stone slabs, and, if accessed by a vertical shaft, the shaft was filled in with stone or sand. The burial chamber could be used or reused for new burials over a period of several generations before it was abandoned.2 Often, the burial chamber was not decorated, although there are exceptions.3

The tomb of Menna (TT 69) is, in many ways, an ideal Theban tomb structure. It is situated in a slightly sunken, enclosed forecourt. The plan of the tomb chapel is in the form of an inverted ‘T’ composed of a broad transverse hall and a long inner hall with a shrine at the end (Figs. 1.1, 1.2). Cut into the rock of the upper enclosure of Sheikh Abd al-Qurna, TT 69 lies adjacent to the tomb of the ‘high priest of Amun,’ Mery-Ptah (TT 68), which lies above TT 69 to the northwest; tomb C4 belonging to Mery-Ma’at, a ‘Wab-priest of Ma’at,’ is situated slightly to the northeast; and the tomb of Nakht (TT 52), an ‘hour-watcher of Amun,’ below the hill to the southeast (Fig. 1.3).4

The tomb of Menna has never been scientifically published. It was originally discovered by Gaston Maspero in 1886 and cleared by Robert Mond in 1903–1904 for the Antiquities Service.5 At the time Mond began the clearance, the tomb was already known by the local population, and to visiting Europeans through guidebooks. Since, the majority of the decorative program in the chapel has been documented, beginning with Colin Campbell, who did facsimile paintings of the decoration in 1910,6 and most recently, Mahmoud Maher-Taha in 2002.7 On the other hand, the textual program has never been fully examined.8

Figure 1.1: Ground plan of the tomb chapel of Menna (TT 69).

Figure 1.2: Tomb chapel of Menna sections.

Figure 1.3: TT 69 and surrounding tombs, Sheikh Abd al-Qurna.

Most of what is known of the original structure comes from Robert Mond’s clearance of the tomb for the Antiquities Service in 1903–1904. Mond noted that the courtyard of TT 69 was accessed by mud-brick steps and surrounded by a wall. Today, the courtyard sinks roughly 80 cm below the floor of the necropolis, and is accessed by a modern stone ramp (Fig. 0.1). Originally, the entrance to the chapel was framed by two inscribed doorjambs with an unpainted limeplaster lintel, all of which no longer remain.9 The modern entrance today is constructed of concrete.

Figure 1.4: Right exterior entrance-wall of the tomb chapel, covered with three layers of brown mud plaster with limestone chips and a layer of gypsum plaster. Remains of the pharaonic mud-brick wall can be seen to the far right. The Theban limestone dips appreciably to the far-right corner of the forecourt where the inner ceiling collapsed.

The walls adjacent to the entrance are composed of a mixture of ancient and modern mud brick. The wall to the immediate right is covered with three layers of light-brown marl plaster with chips of limestone and the remains of a layer of beige gypsum plaster (Fig 1.4). Above, the very brittle native Theban limestone dips appreciably to the far-right corner of the forecourt. Behind this wall, inside the chapel, Ernest Mackay noted that the ceiling above the right wing and part of the left wing of the Broad Hall had collapsed, leaving only 127 cm of decorated ceiling above the left broad-hall wing.10 Three wooden beams, and later four light iron girders, were set up to support the ceiling.11 A series of photographs taken by Harry Burton for the Metropolitan Museum’s Egyptian Expedition clearly depicts an arched ceiling composed of mud plaster at the far right of the Broad Hall, and a beam running between the lateral walls as a support for the roof (Fig. 1.5). As discussed in chapter 4, the Long Hall was secured by a similar arrangement of wooden beams.

Figure 1.5: The old wooden bracing system in place around 1920–21 on the right wing of the Broad Hall Ceiling (BHC). Photography by the Egyptian Expedition, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Inside the Broad Hall on the right-hand side, nearest the entrance (BHNR), remains of a color band can be seen that bordered the initial entrance door of the tomb, approximately 150 cm from the edge of the modern entrance. (Compare Figure 2.8a and Figure 2.8b.) At some point, the Broad Hall of the tomb was extended to the southeast and a new entrance door was cut that roughly conforms to the modern door today. The original door was filled in with a combination of limestone chips and muna (a mixture of mud and chopped straw). Based on the similar pigment recipes from the first and second phases of decoration ascertained by X-ray fluorescence, the movement of the entrance was contemporary with the original decoration of the tomb. The artists did not change the original scenes and texts (rendered in blue line), but simply moved them to the right to coincide with the new door.12

A two-by-two-meter square was cleared in the forecourt floor directly before the outer wall, positioned to correspond with the earlier color band inside the chapel on BHNR, to see if the remains of the original door could be ascertained (Fig. 1.6). This earlier door is also noted by a dotted line on Figure 1.1. The inset shows the remains of the original entrance plaster that was part of the raised doorstep that led into the tomb.13

Figure 1.6: Remains of entrance step to TT 69, composed of plaster underneath the muna–limestone fill. The exposed doorstep is 57 cm long x 4.5 cm high. It occurs approximately 143 cm from the right edge of the modern door jamb.

The question remains: why was it necessary to move the door? One reason could be the bad quality of the rock. When constructing a Theban tomb, a passage was hewn into the rock that conformed to the height (and perhaps length) of the structure. Red lines indicated the central axis of the tomb (and at right angles, the transverse hall, if cutting a T-shape tomb).14 Once the basic tomb was cut, the plasterers and painters would go to work. If one looks carefully at the right wing of the Broad Hall in the chapel, the bottom corners of the shrine wall were not straightened, due to the quality of the rock. The stability of the ceiling over the right wing may also have been a concern to the workmen.

Another reason may be the existence of another tomb to the right of TT 69 that was discovered or known when Menna’s tomb chapel was under construction, but its exact coordinates are lost today. The debris mounds and hillocks between TT 69 and the forecourt of TT 68 remain unexcavated and could yield a previously discovered or unknown burial. The dotted square conforms to an existing shaft and may point the way to where the tomb is to be found (see Fig.1.3). Whatever the reason, the artists quickly discovered the error and extended the tomb to the left, moving the decoration and texts with it.

Moving back outside to the forecourt and to the walls of the west and east elevation, the layer of Theban limestone is capped with a modern stone wall that levels off roughly two feet above the modern doorway (indicated gray on Fig.1.1). At the top of the stone wall, a modern roof covered with a layer of scree (small loose stones) stretches about 6 m back from the tomb’s entrance doorway to the beginning of the Long Hall (see Fig. 0.1). A higher modern stone wall rises above the roof and forms a semicircle that steps down on both sides, ending at the level of the necropolis floor to the southeast, and turning slightly toward the north on the northwest. Two stone wings extend out from this semicircular wall, leaving an opening of roughly 40 cm to access the stone ramp that leads into the forecourt.

The south elevation of the forecourt is largely reconstructed out of horizontal layers of modern stone (Figs. 1.7a, 1.7b). Horizontal layers (up to one meter) of the pharaonic gray mud brick are preserved at the far-left edge, and a few bricks remain in the center and to the far right. These original bricks can be distinguished from the modern mud bricks by their gray color and dimensions (31–32 x 13.5–14.5 x 9.5 cm).15 In the middle of the western elevation there are remains of the original pharaonic stone wall, covered in areas with a beige marl plaster with limestone chips to even out the surface.

The east elevation of the court is composed of 3.1 m of modern mud brick from the right edge to the center of the wall at a height of 2 m. The original entry jambs to tomb –312-16 can be seen made of mud brick covered with beige marl mortar with chips of limestone. The remaining 3.3 m of wall is the rock face. In the northern elevation, the two small wings to either side of the ramp to the forecourt were originally composed of two courses of mud brick in 1903–1904, according to Mond. A few bricks remain on the northwestern side. Today, they are constructed of the same type of modern stone used for the retaining walls around Menna. Below the wings, areas of the rock face are coated with a layer of marl plaster, with and without limestone chips.

Although the various modern additions to the forecourt and enclosure wall of TT 69 make it hard to reconstruct its original arrangement, a few suggestions are offered here. The façade and wing walls were worked out vertically from the rock and the forecourt was cut about 0.8–1 m into the limestone floor. The brittle limestone rock face of these walls was covered with a beige marl plaster, reinforced with straw and limestone chips of varying sizes, and painted with a light brown-beige wash to create an even surface. Above the limestone, mud-brick walls were constructed to even out the irregular height of the rock face. The height of the original mud-brick walls cannot be determined today due to the limited remains. The modern stone wall that encloses the tomb of Menna on three sides obscures any earlier construction not mentioned above.

Figures 1.7a and 1.7b: Structure and elevation of the forecourt walls of TT 69.

Figure 1.8: Tomb-chapel wall measurements of TT 69.

As stated above, the ground plan of TT 69 was arranged in the form of an inverted ‘T’ composed of a broad transverse hall and a long inner hall with a shrine at the end surrounded by a painted entablature (Fig. 1.8).17 This plan was one of the most common in the Sheikh Abd al-Qurna necropolis. The tomb chapel measures 11.49 m from the entrance door to the shrine wall, and about 8.96 m wide in the Broad Hall. The elevation of the chapel ranges from approximately 2.28 m in the Broad Hall and 2.04 m in the Long Hall, but the original measurements can only be approximated due to the unknown level of the original ceiling in the Broad Hall and the original levels of the ancient floor. Since the tomb was cut into a layer of poor limestone, the surface was equalized with a combination of muna plaster composed of mud and hacked straw, sometimes reinforced with limestone chips. The muna was coated with gypsum plaster followed by a smooth, fine layer of gypsum on which the decoration was applied. The techniques and materials used for the decoration will be discussed in chapters 3 and 6.

As mentioned in the Introduction, the Tomb of Menna (TT 69) Project used non-invasive methods of examination. For this reason, archaeological excavation was never a part of the original conservation and documentation plan. This noted, a few words could be said about previous excavations in order to understand the use and reuse of the monument. Mond recorded the presence of six burials, three of which were sunk into the floor of the tomb chapel or courtyard (pits 1–3). The other three burials (pits 4–6) were excavated “beyond the boundary of the courtyard” and can no longer be localized (Fig. 1.9). Of these, Mond’s pit no. 1, the sloping passage in front of the shrine wall, was destroyed by fire. In it were found an ivory spoon, gilt plaster cartonnage fragments, part of a pectoral ornament, a blue faience lotus column amulet, and a wooden furniture leg belonging to a chair or bier. Mond assigned the finds from the sloping passage burial to the Twenty-sixth Dynasty. In the second burial, in front of the left focal wall of Broad Hall Far Left, he found “fragments of a mummy of no importance.” In the third, in a pit to the left of the mud-brick entrance ramp, Mond found a “ceremonially broken” wooden staff that was bound at the top with a string. A staff conforming to this description and excavated by Mond in 1903 is currently in the Cairo Museum (JE 36802) (Fig.1.10). Outside of the courtyard, in the sixth pit, a 21-cm-high limestone bust of a woman was found. This fragment belonged to Menna’s wife, Henuttawy, and was once part of the pair statue found in the tomb chapel’s shrine (JE 36550) (Fig. 1.1).18 In the debris surrounding the pits, Mond found a number of extraneous funerary cones, belonging to Mentju (Mn-ṯw), Nakhtamun (Nḫt-ỉmn), and Mery (Mry). The shaft in the forecourt and the sloping passage burial in the chapel before the statue shrine likely originated from the time of Menna. Recent research indicates that the sloping passage began to be used in private tombs in the Middle Kingdom.19 Mond’s dating of the sloping passage was based on the Twenty-sixth Dynasty objects found in there; he did not consider a later reuse of Menna’s original burial.

Figure 1.9: TT 69 plan and burials recorded by Robert Mond in 1903–1904. (R. Mond, “Report of Work in the Necropolis of Thebes during the Winter of 1903–1904,” 24).

Figure 1.10: Menna’s staff, Egyptian Museum, Cairo, JE 36802. Image © The Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

The last point concerns the placement of the tomb in the Sheikh Abd al-Qurna necropolis. If one follows the geography of the necropolis, the valley depression in the adjacent necropolis of Khokha is bounded by tombs dating to the reign of Amenhotep III on the north (TT 48, TT 257, TT 47, TT 107), and tombs dating to the reign of Thutmose IV on the south (TT 175, TT 38, TT 108); it passes by the courtyard of the tomb chapel of Menna (TT 69) (Fig. 1.12).20 This depression probably served as a processional route because it led directly into the valley to Deir al-Bahari, which was the goal of the divine barques during the Valley Festival, the annual Theban necropolis ancestor festival during which living relatives celebrated the dead in their tomb chapels. In fact, several tombs that lie along this Khokha depression use the ‘Appeal to the Living’ text in their tomb chapels to call to the participants in the Valley Festival “as they walk (stwt.sn) in procession in the august valley … ” presumably past the chapel doors of these tombs.21 Menna also references this procession on the left entrance door, in which he says “I behold you in your beautiful festival, at your sailing to Deir al-Bahari (ḏsr-ḏsrw).” Another processional route configuration takes a southwesterly route from the Khokha depression past the tomb of Menna, down to the tomb of Nakht (TT 52), to a collection point in the lower enclosure of Sheikh Abd al-Qurna (Fig. 1.13).22 The siting of the tomb of Menna toward the northeast would have taken advantage of both necropolis processional routes, and joined the tomb owner in perpetuity with the festivities. The sighting of prominent tombs along necropolis streets likely reflected the tomb owner’s desire to act both as a participant in the festivities in perpetuity, and as a supplicant to its celebrants to say a prayer or leave an offering.

Figure 1.11: Statue bust of Henuttawy, right half of the pair statue of Menna and his wife from TT 69. JE 36550. 21 cm high. Image © The Egyptian Museum.

Menna and his Family

Little is known about Menna other than from his tomb. A few texts were painted inside the chapel, but many scenes contain blank white backgrounds and/or column lines that never received their final texts. As discussed above, the previous plundering of the tomb and the meager burial goods offer little insight into Menna’s life. Therefore, one must turn to the titles preserved in Menna’s tomb:

Scribe—sš Overseer of Fields of Amun—ímy-r ɜḥwt n ’Imn Overseer of Plowlands of Amun—ímy-r ḫbsw n ’Imn Overseer of Fields of the Lord of Two Lands—ímy-rɜḥwt n nb -tɜwy Scribe of the Fields of the Lord of Two Lands of South and North—sšɜḥwt n nb tɜwy nw šmɜw mḥw Scribe of the Lord of Two Lands—sš n nb tɜwy

Menna’s primary titles indicate he was a scribe and overseer of fields belonging to the Amun temple and a royal field scribe for Upper and Lower Egypt. As overseer of plowlands of Amun, he also administered new temple land (ḫbsw) to be cultivated by a labor force.23 As the overseer of the fields (ímy-r ɜḥwt), Menna would have supervised a number of field scribes, and reported to the central field administration in the office of the granaries of the pharaoh.24 Scenes depicted in Menna’s tomb elaborate on his duties, and show that he supervised delegations who measured the fields, brought defaulters to justice, inspected field work, and recorded the yield of the crop.

The administration of both state and temple fields at the same time by one person is unusual, and limited to Menna during the Eighteenth Dynasty. Usually, the administration of temple fields was separated from fields under state control.25 However, the Ramesside Wilbour Papyrus may offer a clue. The Wilbour Papyrus illustrates how temple-owned lands were a special form of state property owned by the pharaoh.26 During the reign of Amenhotep III, the king’s vast building program drew on the wealth of Egypt, and its success depended on the stability, accumulation, and redistribution of natural resources like grain. For this reason, the different offices of grain administration may have been centralized under Menna for greater efficiency.

Figure 1.12: Necropolis of Khokha (Porter and Moss, Topographical Bibliography, vol. 1, part 1, 2nd ed., pl. iv). Copyright: Griffith Institute, University of Oxford.

Figure 1.13: Necropolis of Sheikh Abd al-Qurna, North (Porter and Moss, Topographical Bibliography, vol. 1, part 1, 2nd ed., pl. iv). Copyright: Griffith Institute, University of Oxford.

In nearly every scene, Menna is depicted wearing the shebyu-collar (šbyw), also known in ancient Egyptian texts as the Gold of Honor (nbw n ḥswt). The Gold of Honor indicated that Menna received recognition from the king himself, and occupied a high office that directly related to the king and his royal holdings.27 In the reign of Thutmose IV, temple officials such as Amenhotep-sa-se (TT 75) and artists like Kha (TT 8) were awarded the Gold of Honor. However, it was in the reign of Amenhotep III that high officeholders who managed the resources of Egypt were awardees. It appears the king awarded the Gold of Honor to those whose loyalty was critical for the success of the pharaoh and Egypt’s internal management. For example, in his tomb (TT 57), Khaemhet is depicted before Amenhotep III wearing the Gold of Honor with the following caption:28

The King appearing on the great throne in order to reward the controllers of Upper and Lower Egypt. (1) Rewarding the overseers of the estates (2) of Pharaoh, l.p.h. [life, prosperity, health] (3) together with the controllers of Upper and Lower Egypt (4) after the overseer of the two granaries had said about them: “They have given (5) more than their harvest of Year 30.”

The text clearly states that a group of “controllers of Upper and Lower Egypt” had received the Gold of Honor after an exceptionally good harvest that probably coincided with one of the king’s Sed Festivals in years 30, 34, or 37. Menna, a field overseer for Amun and the crown, and scribe of the fields of the North and South, was an official who controlled the distribution and taxation of grain. Menna may have received the Gold of Honor from the king after a year in which the harvest was particularly good. If he received the award the same year as Khaemhet, who was an overseer of granaries of Upper and Lower Egypt, this would place Menna’s career well into the reign of Amenhotep III, past the ruler’s year 30.

Menna also appears to have married well. His wife, Henuttawy, figures prominently in the tomb and appears in nearly every scene in the chapel. Her titles indicate she served as a ‘Chantress of Amun’ (šm’yt nt ’Imn), a popular occupation for noble women in the Eighteenth Dynasty.29 She also bore the title ‘Mistress of the House’ (nbt-pr), which indicates that she probably came into the marriage with property.30 Concerning her parentage, Henuttawy may be the daughter of Amenhotep-sa-se, the second prophet of Amun—the next-to-highest office in the powerful Amun temple precinct at Karnak—and the owner of Theban Tomb 75.31 TT 75, which is dated by cartouche to the reign of Thutmose IV, depicts a daughter named Henuttawy (ḥnwt-tɜwy) who bears the title ‘Chantress of Amun.’ In TT 69, Henuttawy is spelled eitheror , sometimes even on the same wall, while in TT 75, only the latter spelling is used. Although the name Henuttawy (meaning ‘Mistress of the Two Lands’) was a fairly common name, it is found primarily in Theban tombs dating to the period of Thutmose III–Amenhotep II.32 Another indicator of her parentage lies with the name of Menna’s son Se, who could have been named after Henuttawy’s grandfather, Se. This lineage is recorded in the name of Henuttawy’s father Amenhotep-sa-se, which literally means ‘Amenhotep, son of Se.’33 Amenhotep-sa-se’s wife, Ray, was a lady-in-waiting in the royal court (ẖkrt nswt),34 a position that was also held by the daughter of Menna and Henuttawy, Amenemweskhet (ỉmn-m-wsḫt). Another daughter, Nehemet (nḥmt), may also have served in this position because she is depicted with the distinctive crown associated with ladies-in-waiting.35 Based on these points, Menna’s genealogical link to Amenhotep-sa-se through his wife Henuttawy is accepted here, but with caution (Fig. 1.14). If Menna was married to Amenhotep-sa-se’s daughter, then he was born sometime at the end of the reign of Amenhotep II, and married Henuttawy during the reign of Thutmose IV or early in the reign of Amenhotep III.

Menna had two sons, whose titles are recorded in TT 69: Se, a “scribe of counting grain of Amun,” who followed his father’s career, and Kha, an entry-level wab-priest. Wab-priests, meaning ‘pure ones,’ were minor clergy who played a secondary role in the daily cult ritual for the gods and other sacred activities. Menna had three daughters. Amenemweskhet was a lady-in-waiting who also bore the epithet “praised of Hathor.” Nehemet was “praised of Amun” and also wears a crown similar to Amenemweskhet, suggesting that she too was a lady-in-waiting to the royal court. She, however, is described in that scene as “justified” or “true of voice” (Mɜ’t-ḫrw), and probably was already dead at the time the Broad Hall was decorated.36 The last daughter, Kasy (kɜsy), appears on several walls, but without titles. Two additional women appear in the tomb chapel: Way (wỉỉ) and Nefery, (nfr(ỉ)ỉ), who were both chantresses of Amun and mistresses of the house, the latter title indicating they were married.37 It is possible that these women are, in fact, daughters-in-law of Menna; they are designated as sɜt, which usually means ‘daughter’ but can hold the extended meaning of ‘daughter-in-law.’38 Likewise, these women appear directly beneath Menna’s sons on the Valley Festival Wall (BHNR), which often indicates a relationship. Other children may have appeared in the chapel decoration, but are unidentified.

Figure 1.14: Family Tree of Menna.

Images of Menna were consistently destroyed by an enemy in an act of damnatio memoriae, ‘condemnation of memory,’ the condemation of the deceased to oblivion. Tomb images were given life through rituals, such as the Opening of the Mouth ceremony, which allowed the images of the deceased to breathe, see, taste, smell, and hear. Thus any disfiguration of these images would result in their compromised efficacy and were an act of condemnation. Menna’s damnatio memoriae took the form of damage to his eyes, nose, and mouth. However, this did not hamper Menna’s well-being entirely: his name—an aspect of his soul and an important component of his identity39—was left largely intact in the tomb chapel texts until the Amarna period. At that time, the first part of Menna’s name was destroyed, when his titles associated with the properties of Amun appeared before it. In the case of his wife Henuttawy and other figures, the destruction was more random, suggesting it originated at a later point, perhaps when the tomb was reused during the pharaonic and Coptic periods.

Date of the Tomb Chapel

The majority of studies date the tomb of Menna (TT 69) to the reign of Thutmose IV.40 However, a few works point to the tomb chapel’s manufacture during the transitional period of kings Thutmose IV/Amenhotep III,41 or some solely to the reign of Amenhotep III.42 Despite the debate, the bulk of the evidence points to its manufacture during the reign of Amenhotep III. The tomb chapel was definitely completed before the reign of Akhenaten, whose agents destroyed the name of Amun-Re and depictions of sem-priests (funerary priests) on almost every wall. Since no cartouche was ever recorded in the tomb, a number of factors must be weighed. As mentioned above, Menna probably received his Gold of Honor later in the reign of Amenhotep III, after year 30. Architecturally, the layout of the court and the tomb is toward the southwest, presumably to take into account the existing court of Mery-Ptah (TT 68) that dates to the reign of Amenhotep III, after year 20.43 The court of TT 69 is surrounded on all sides by a sunken court that was accessed by a ramp. Parallels for this feature are found mainly in tombs dating to the reign of Amenhotep III (TT 54, TT 139). Inside the chapel, painted details such as an elongated unguent cone44 on the head of the deceased and his wife, similar ocher-toned skin color between men and women, faces with small noses and mouths, elongated eyes with pupils that disappear under the upper eyelid, and straying wig tendrils, are common in figures that date to the reign of Amenhotep III.45 However, the painting on the right focal wall of Broad Hall Far Right (BHFR) retains a few of the stylistic indicators of painting from the reign of Thutmose IV that may indicate an artist working in an earlier style or an earlier phase of decoration in the chapel (see chapter 6).46 The figural proportions and dresses of the women in TT 69 also support a date in the reign of Amenhotep III. Furthermore, the painting style in TT 69 is very similar to the chapels of Pairy (TT 139) and Neferrenpet (TT 249), both of which are dated to the reign of Amenhotep III by cartouche.47 Also remarkable is the similarity between the Osiris hymn in TT 69 and that of TT 139.48 Last, but not least, the bust of Henuttawy in the Cairo Museum (JE 36550), one half of the paired statue that sits in the niche of TT 69, is sculpted in a style that can only be assigned to the reign of Amenhotep III (see Fig 1.1).49 All of this evidence points to the bulk of the tomb chapel’s manufacture and decoration during the reign of Amenhotep III, probably after the ruler’s year-30 Sed Festival. However, it is important to note that the construction and some of the decoration may have occurred earlier in this king’s reign as evidenced by the artist working on BHFR.