Читать книгу The War at Home - Helen Bradford - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Foreword

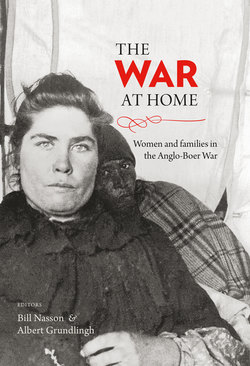

ОглавлениеTHIS COLLECTION OF ESSAYS, edited by Bill Nasson and Albert Grundlingh, is a significant reassessment of the Anglo-Boer War, portraying the civilian experiences of the war as bleak yet also endurable. Focusing on the plight of women and families, the contributors consider not only their victimhood but also, more importantly, their own human agency. Through a meticulous reading of the written and photographic archival material, the authors provide a detached account, allowing the reader to appreciate the subtleties of the relationships between gender, race and class in the context of a colonial war. The quality of the images and the unfolding details in this book are astounding. Women and young girls are shown with domestic products such as a broom, bucket, chair, blanket and pot. And each person is in their, seemingly, rightful place. At home? But their homes no longer exist, having been destroyed during the scorched-earth policy or involuntarily abandoned.

Homes are now tents – makeshift abodes for these nomads who live in concentration camps. In the photographs, the gazes of these people reflect both their fear and determination – the weaknesses and strengths of those transformed by their predicament.

Much like a cinematographic flashback, the book uses the inauguration of the Women’s Monument in Bloemfontein in 1913 as a symbolic foundation. Its centenary is subtly contextualised within a complicated and horrific colonial war and the consequent rise of segregationist nationalism. One of the methods of imperial warfare was the concentration camps, which were designated primarily (yet not exclusively, according to one contributor) for civilians, specifically women and children, whether they were black or white. The scorched-earth policy, which was introduced by the British army in an increasingly professionalised way, had consequences beyond the brutal ordeals of these women and their families. Their incarceration also left a lasting legacy on the history of the country.

Another visible flashback here is the origin of the camps. For political writer Hannah Arendt, concentration camps came into existence long before the totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century made them an important institution of government. They were not the same as prisons. Rather, they were meant to deal with people who were ‘undesirables’ – individuals who had lost their legal rights and identity in their own country.[1] Hannah Arendt was one of those scholars who mistakenly attributed the rise of concentration camps to the Anglo-Boer War. In fact, as the first chapter by one of the editors also notes, their origins lay elsewhere. Essentially, they were invented in 1896 in Cuba under Spanish General Valeriano Weyler y Nicolau. They came to be refined in South Africa and went on to be implemented worldwide in the following two decades. Indeed, they continue to exist in the present day.

What exactly happened? Civilians – particularly women, children and the elderly – were incarcerated and treated as the enemy because they found themselves encircled by war. For the most part, these non-combatants were becoming accustomed to some state of emergency or martial law because this had been a part of the colonial experience and the rise of a total war. They were subjected to brutal hardships, including loss of freedom, separation from loved ones, deplorable and unsanitary living conditions, lack of food, overcrowding and disease. They had to endure under policies that did not originally have the intent to make them suffer or die. Their detention was either administrative or military but not legal, because they were never tried or condemned.

It is important to consider briefly what happened in Cuba. There, in the mid-1890s, the Spanish army’s concept of a ‘concentration of civilians’ led to the invention of camps, bearing the name reconcentrados. General Weyler’s idea was to separate the civilians from the rebels who opposed Spanish colonisation, under the pretext of protecting them from the scorched-earth policy that was designed to end the Cuban insurgency. They were to be deported and isolated in a type of exile. In other words, individuals were to be removed from their homes and transported elsewhere. Weyler understood that the Cuban rebels were reverting to guerrilla tactics and were being fed, voluntarily or otherwise, by civilians. In order to win the war, Weyler decided to cut those resources by ‘reconcentrating’, or relocating, the civilian population and dividing the island into zones. In March 1898, an eyewitness, American Senator Redfield Proctor, said that ‘it is not peace, nor is it war. It is desolation and distress, misery and starvation’ with every ‘woman and child and every domestic animal under guard ... It is concentration and desolation.’[2]

Mass media emerged during this period, and journalists were able to report on the suffering of the Cubans to a world audience. In addition, the increasingly professional photography of war covered such acts of political extermination.

The Spanish imperial power’s defence was based on the belief that the Cuban enemies were barbarians. Regardless, the civilised world was expected to protest and intervene, and the Cubans looked to the United States in the hope that it would recognise their independence. Instead, the Americans invaded the island against the will of its inhabitants and imposed a de facto American protectorate. By 1898 this, at least, ended the forced removals.

For his part, Weyler had implemented a tactic that he had already witnessed on a smaller scale in the United States. During the American Civil War of 1861–1865, he had been Spain’s military attaché in Washington and an avid admirer of General William Sherman, who used this tactic against those civilians who were hostile towards the Union forces. Most notably, such civilians in Missouri were displaced and put into what were called ‘posts’. The use of extreme force against civilians (which had been intensifying during colonial conquest) could be justified by authorities on the basis of the racial climate of the time, especially if those being conquered were non-Christian. However, in Cuba, the forced removal of civilians, in the context of colonialism and counter-strategy to guerrilla warfare, involved a population that was of European extraction and Christian.

Turning again to South Africa, it should be remembered that British (and American) opinion considered Weyler a ‘butcher’ and a ‘brute’.[3] The Cape Argus of 26 March 1897 (a local British-colonial publication) described Spain as a ‘disgrace to civilisation’. Shortly after this, the same causes led to the same effects, and a colonial war between the Boers and the British generated yet another system of concentration camps. Aware of what was developing in South Africa, Lloyd George, a Liberal member of the opposition, expressed his concerns to the House of Commons on 25 July 1900, declaring that ‘it seems to me that in this war we have gradually followed the policy of Spain in Cuba’.[4] At this point, it may not yet have been entirely the case, but the military failures of General Frederick Roberts and the imminent arrival of General Horatio Kitchener would soon seal the fate of the Boer and black South African population.

This volume of social history is exact and original in its revisiting of this total war – a war characterised by the destruction of farms, the killing of animals, the widespread use of arson and interpersonal violence between men and women. Contributors carefully explore themes such as the complex relationship between charity and Anglicisation: the British authorities only accepted the former because they anticipated it leading to the latter. The authors also enable the voices of the unofficial prisoners to be heard from their hospital beds, their schools, their places of worship, and through their romances and their deaths, thereby giving a picture constantly illustrated by rich documentary and visual sources.

It all unfolds in the summer of 1900. The British have a military advantage over the Boers. They have control of the cities and rail network, but are still far from winning the war in the face of their adversaries. So they begin the classic method of deporting military prisoners to Saint Helena, Bermuda and India. Protection in camps is even offered to those who surrender. Nonetheless, the guerrilla forces continue to generate mayhem for the British army and the idea of internment of families in concentration camps is considered an extension of the scorched-earth policy. The British believe that the only viable solution would be to destroy the farms and the harvest, and to cut off supplies to the Boer troops. Kitchener sets out to resolve the problem when he takes command at the end of 1900. For him, there are no innocent bystanders among the Boer population – and the testimonies of those who resist, discussed in this volume, fail to prove otherwise! Kitchener focuses on dissuading Boer resistance, and insinuates, despite the evidence, that the ‘joiners’ themselves suggested internment camps for their families. In reality, virtually the entire population is taken hostage. White and black people are all taken as prisoners of war and subjected to harsh reprisals. Moreover, the camps are run by the military with their own clearly punitive goals.

This was the atmosphere, and those who appeared to be victims reacted accordingly. The example of Nonnie de la Rey is of particular interest. She wanted to be considered a prisoner of war in the event of her capture. This would ensure that she would be protected under the first Geneva Convention, or be viewed as neutral under the humanitarian laws that were vaguely in place during the war. Nonnie was a product of the prevailing Boer patriarchal system and she considered herself a ‘man’, in practice a substitute for her man during his absence. Even if she could not expect the British to respect this decision, she continued to support her husband on commando, where active combatants fought side by side and, at times, women accompanied men. It was for this active role, above all else, that she refused to be incarcerated in the concentration camps. Unsurprisingly, the French, Dutch and Belgians (fuelled by anti-British sentiment) eagerly rallied in support of such an austere and relentless freedom struggle by European Calvinists.

As seen in the pages that follow, the British described the Boers as primitive and unrestrained sensual beings, with a strong sense of family values, who would only submit if their kin were affected. At the turn of the century, reference was made at times to ‘Boer herds’ or ‘Boer flocks’, depictions which drew on social Darwinist ideas of human evolution and placed the enemy at a sub-human level.[5] With little choice but to submit, they were enclosed in a camp, which represented a kind of human zoo. There, they were registered, housed in tents, given ration coupons and became names on lists. The process was haphazard.

Neither Roberts nor Kitchener had considered the consequences of their orders. Pushing civilians into cramped quarters with poor sanitation and feeding them on reduced military-level rations could only lead to a disastrous outcome. Already, more British soldiers were dying from disease than in battle, a phenomenon not uncommon in nineteenth-century warfare. In the camps women, children and the elderly were prone to the same fate. Devastating outbreaks of measles were particularly common and later became symbolic of the trauma of camp life.

By the autumn of 1900, high mortality rates were causing a stir among pacifist groups in London, such as the South African Conciliation Committee. Emily Hobhouse, the founder of the South African Women and Children Distress Fund, belonged to this committee. In December 1900, she arrived in South Africa and produced a report on concentration-camp conditions which served as an indictment of the camps. Although not entirely anti-British, this was used to the advantage of the Boers and countries opposing Great Britain (the first translation of the report came from France). Although Emily Hobhouse was expelled from South Africa during her second trip in 1901, her message had been heard in Great Britain. The Liberal Party leader, Campbell-Bannerman, spoke scathingly of his country’s use of ‘methods of barbarism’[6] and made Hobhouse’s report public, an action which led to a subsequent parliamentary inquiry.

The inquiry focused on the desperate situation in white camps. Yet the separate camps established for black Africans were even worse. Their dwellings and plots were also burnt to prevent guerrillas from obtaining resources to continue their resistance.

These inmates worked in the camps and were expected not only to tend to their families, but also to meet some of the needs of the British Army. The high mortality rate in the black camps was largely overlooked by white observers and resulted in little protest and few witness testimonies.

Instinctively, the British tried to deflect their culpability by blaming the unsanitary conditions in the camps on the Boers; their ignorance and inability to be civilised were said to be the cause of the problems. In a complete reversal of the Victorian, British values that glorified the countryside as opposed to industrial cities, the Boers were frequently depicted as primitives living in rural squalor, incapable of cooking the food that was provided and unable to care for their children. To explain this, the authors of this book place the plight of women, children, black servants, white bosses, sick people, caregivers and early humanitarians within a broader reflection on the war. The reader bears witness to the inflicted trauma, the resilience, the helplessness, the loss and the trials of a daily existence. Moreover, a glimpse is provided into the monotony of life that introduced the notion of the ‘barbed-wire syndrome’ familiar to many prisoners – part of a litany of misfortunes that made these civilian camps the first of their kind in the twentieth century.

As the essays indicate, camp conditions gradually improved during the war. By 1902, nurses and teachers from Britain were being employed to care for the sick and the children. Was this in the tradition of Protestant charity? Was it an aspect of civilising enlightenment? Arguably, not quite. For instance, the English language was to replace Afrikaans, in addition to other cultural impositions. Yet, ironically, the political situation was also changing by then because civilians whose farms had been destroyed were no longer being rounded up and incarcerated. In the middle of that dispersion of civilians and erosion of the last of commando resistance, surrender came.

By then, the British had inadvertently created exemplary victims for the Afrikaners to mourn. The existence of the concentration camps gave more impetus to white Afrikaner nationalism than the rest of the colonial experience. Globally, too, the focus was no longer on Cuba. Although the pro-Boer movement stemmed from opposition to the British Empire and colonialism, its widespread outcry – even if exaggerated at times – against what were viewed as crimes, had a genuine basis.

In the September 1901 issue of L’Assiette au Beurre (which was swiftly translated into Dutch), the artist Jean Veber presented several sinister illustrations from the ‘reconcentration camps of the Transvaal’, as they were then referred to. The drawings included depictions of women mourning the deceased children who lay around them and of British soldiers who hit them or separated them from their children. Alongside the illustrations were captions taken from Kitchener’s reports to the War Office in London, emphasising the benefits to Boer women of ‘spacious tents where air and freshness are in abundance’ and camps where ‘jovial mothers’ are able to forget ‘the melancholy of their predicament’.[7]

In these stark expressions, was there perhaps a risk that extreme forms of propaganda would actually dilute opinions of real atrocities? Would such propaganda not inevitably affect public opinion of the civilians who fall prey to the horrors of war? Would the Boers, who had been victimised by the British, not then seek revenge on black African people because the British had employed them against the Boers? Could one still question ethics within war when combatants were no longer the sole protagonists? Was there ever any possibility of considering the idea of a just or unjust war? After all, from this turning point, the use of concentration camps was going to be part of the machinery of war. The camps of the Balkan Wars and the Great War of 1914–1918 were quick to follow those of Cuba and South Africa.

Therefore, among all the hostile powers of the Great War, the internment of so-called ‘suspicious’ civilians was common, as was treating them like prisoners of war in breach of international laws. In occupied lands, suspicious civilians were also the victims of reprisals and were, at times, deported and/or sent to work camps. Incarcerating non-combatants as a means of weakening the enemy had always been a strategic method of warfare. And, obviously, the simultaneous capturing of soldiers was far from novel. By contrast, the advent of concentration camps since the events in Cuba and South Africa was an innovation in warfare: ordinary civilians, too, had become victims on the path towards total war. Their camps had become an integral part of the culture of armed warfare.

In many ways, between 1896 (the war in Cuba) and 1918 (the end of the Great War), the Anglo-Boer War also contributed to these changes in the conduct of war during the twentieth century. In South Africa, the deportation and incarceration of civilians had not culminated in mass extermination. But conditions did produce a war against civilians characterised by extreme violence. At the same time, the camp phenomenon was not yet synonymous with the later organised systems of concentration camps. In the Anglo-Boer War, the management of the camps was haphazard and uncoordinated, as this book clearly reveals. Regardless, this was still a total war. Total war requires the incarceration of enemies, be they soldiers captured during battle or civilians perceived and treated as enemies – unarmed soldiers who used their own weapons of hatred, refusal and silence to fight back and prove their resilience.

Clearly, the experience of the Boer people in the republics in South Africa was not that of genocide, as in the experience of the Armenians of Turkey in the Great War. It was that of degradation. The causes thereof were not accidental, inadvertent or intentional cruelty, but rather the essence of war policies in occupied territories, namely, incarceration and isolation. It is on that path that one finds the tragedies and horrors of the victimised women and families of the Anglo-Boer War.

Annette Becker is Professor of Modern History at the Paris West University Nanterre La Défense, and a senior member of the l’Institut Universitaire de France. A social and cultural historian of total war in the twentieth century, she is an authority on the impact of violence upon civilians under military occupation. Becker is one of the founders of the Museum of the Great War in northern France, the Historial de la Grande Guerre, in Peronne, Somme. Her recent publications include a study of the World War I experiences of French poet Guillaume Apollinaire, Apollinaire: Une Biographie de Guerre 1914–1918 (2009).