Читать книгу The War at Home - Helen Bradford - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

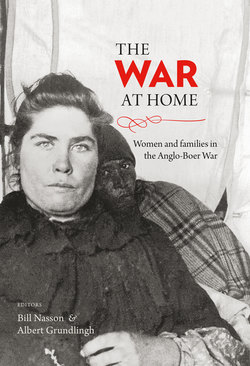

Оглавление| Clawing skywards into life – the Women’s Monument in 1913, towering over the flat Highveld surroundings of the Orange Free State |

Introduction

THE TRAUMATIC IMPACT OF THE 1899 TO 1902 war in South Africa on most ordinary Afrikaner people has often been viewed as the defining feature of the bitter Anglo-Boer conflict. The trauma has lingered in popular memory, and not only as a result of the anniversaries that serve to remind us of the conflict. Nevertheless, commemorations, particularly centenary ones, are potentially more than rituals. They may, in fact, give rise to a fresh outlook on history with which to revisit established perceptions of past events and people. With that in mind, the publication of this book coincides with the 2013 centenary of the Women’s Monument in Bloemfontein, inaugurated after the end of the Anglo-Boer War, which is now frequently also referred to as the South African War.

Like other recent historical works, this book has been prompted by the present era, which has yielded notable centenary commemorations of events in South African history. The start of the twenty-first century has been marked by commemorations of the 1899 to 1902 conflict; the 1906 Bhambatha rebellion in Natal; the initial founding of the African National Congress in 1912; and the 1913 Land Act. And others will take place in the near future, such as the centenary of the 1914 Afrikaner rebellion at the start of World War I and the centenary of the founding of the now-extinct National Party, also in 1914 – likely to be a muted commemoration, in the light of more recent post-apartheid history.

If one were to compare commemorations, the 1913 Women’s Monument and other events would be overshadowed in scope and significance by the 1938 Voortrekker centenary celebrations. At the heart of that occasion lay the awakening of a dormant Afrikaner nationalism, which drew on a momentous past episode to galvanise the volk. Such brazen displays of nationalist excess would look out of place in our own, more sceptical age. Yet, it remains an example of how historical commemoration is always viewed through the lens of the present.

Why should the creation of the Women’s Monument be commemorated in a South Africa that has changed so much since 1913? Is its legacy still relevant and, if so, what meaning does it hold for ordinary South Africans 100 years later?

To answer these questions the authors of this book explore the shifting sands of memory and consider how the monument – a body of stone charged by emotion – has been perceived at crucial historical stages since 1913. We consider the questions of whom it spoke to originally, what it has been seen to say through the twentieth century, and what it might say now. Alongside its perspective on this particular legacy of the conflict, The War at Home: Women and Families in the Anglo-Boer War is concerned with the complexities and contradictions of the war experience of 1899 to 1902, which gave birth to enduring rituals of remembrance.

The War at Home tells readers more than simply the story of this iconic war memorial. Naturally, the 1913 Women’s Monument – with its emotional, political, cultural and other memories – embodies a public history of its own. But it also provides a glimpse into the varied lives and extreme circumstances of a vulnerable civilian society that was directly affected by the shock of a modern total war. The war of 1899 to 1902 was more than one war and more than merely a conflict between armies on the battlefields. Many ordinary rural people – white, black, women, children, families and individuals – experienced the deaths and suffering caused by hostilities beyond the battlefield.

The civilian worlds explored in this book are mainly those of women and families confronted by massive upheaval. Yet, although the collection describes the plight of helpless victims, it also analyses the ways in which the strain of war experience was uneven and often unpredictable. In other words, instead of reinforcing well-worn historical interpretations that reduce the existence of women and families to that of passive suffering, we will examine the vital aspects of civilian endurance – so often overlooked or forgotten.

In confronting the tragedy of the war, the contributors show the endeavours of those who sought to come to terms with the precarious circumstances created by invasion and occupation. Their war was the struggle for a tolerable and decent existence in a complicated landscape of conflicting interests – defiance and accommodation, resistance and collaboration, interaction and withdrawal, fragile certainties and acute insecurities, and hope and despair. If our readers are to remember or commemorate anything about this total war in South Africa, we hope they will gain a sense of perspective when considering what the conflict meant for those who were not under arms.

In the chapters that follow, our contributors look at the powerful implications of gender in wartime, as well as at the personal trials in the countryside of one intriguing and prominent Boer woman who was able to avoid Britain’s concentration camps. The camps are, of course, a particularly controversial aspect of the war. For more than a century, their existence has inspired comment and condemnation from scholars, historians, politicians and sentimental Afrikaner citizenry.

We apply a broad-minded approach when analysing the purpose and nature of the concentration camps, and the reasons for their establishment. We also question the common assumption that the development of the camps was inevitable, based on the justification that the war could not have taken any other direction in the calamitous winter of 1901. In the same way, we deal with the evolution and dynamics of the black camps. Contrary to popular perceptions, historical works have documented their existence for several decades. This book suggests that white and black camps were more intertwined and that there was a greater degree of interaction between their separate inhabitants than has often been assumed.

We also record the experience of family life in the concentration camps. Even though there has been considerable focus on the camps, little is known about the circumstances of interned children. To make up for this historical neglect, this collection offers insight into wartime camp childhoods and provides readers with an understanding of how children survived and expressed themselves. It is time to move beyond the narrow view of their presence counting only as a toll of wasted and dead bodies.

In this way, we turn a searchlight on the complex inner workings of the camps. We investigate the everyday life of inhabitants, as well as how the conflicting medical cultures of the confined Boers and the occupying British administration influenced attitudes towards healing and recuperation. Finally, the common link between the horror of war and black or ironic humour leads us to a consideration of the views of those who resorted to comic expression to cope with their extreme circumstances. We also consider the significance of the comic imagination as the ordinary Boer population dealt with the immediate aftermath of hostilities.

As The War at Home shows, there were many wars fought from 1899 to 1902. With the fighting front and the home front often being indistinguishable, the Anglo-Boer War was a momentous struggle with many facets and faces, some of which are portrayed here. We invite readers to visit, once again, South Africa’s total war.

Bill Nasson and Albert Grundlingh