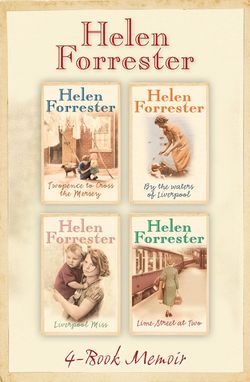

Читать книгу The Complete Helen Forrester 4-Book Memoir: Twopence to Cross the Mersey, Liverpool Miss, By the Waters of Liverpool, Lime Street at Two - Helen Forrester - Страница 26

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

ОглавлениеOne of the penalties frequently paid for being poor is that of being cut off from the rest of the world. The normal means of communication such as newspapers, radio and letters cost money. Some of our neighbours had radios, and they clung to them no matter what else they had to part with. It was their main source of both entertainment and news, as long as they had a penny to put into the electric meter or could afford to get the wet batteries recharged. These families could hear the first rumbling of the Nazi movement in Germany and Mussolini’s fiery speeches, and of strikes and riots in Spain, the prelude to the Spanish Civil War. Nearer home, there was the crisis of the resignation of the Labour Government.

My father read several national newspapers and the Liverpool Echo whenever he went to the library. My mother, also, would skim through the Echo during a quick visit to the library, when she would jot down on a piece of paper details of jobs advertised. They were, however, the exception; most people around us found reading a laborious effort and there was a fair sprinkling among the older inhabitants who could neither read nor write.

The newspaper room in the library seemed to be the preserve of adults, who did not like a dirty ragamuffin with a baby on her hip, pushing in front of them. In consequence, I knew more about Walsingham and Lord Burghley, Queen Elizabeth I’s ministers, than I did about George V’s Ramsay MacDonald.

I knew nobody of my own age and was cut off from all forms of play. Some girls of about fourteen years of age lived in the vicinity. They were tough, brassy lasses, who regarded themselves as adults and worked all day in factories or shops. Each girl had a best friend who was known as her mate and together they went to the cinema or to dances, where they danced together; if a boy asked one of them for a dance she circled the floor with him in silence, her face exhibiting about as much expression as the back of a tram. Every Friday evening they solemnly washed and set each other’s hair, and on Sundays, dressed in their best, they would walk together in the streets, regarding hopeful males with joint disdain. This was a matriarchal society where ferocious grandmothers and nagging mothers reigned supreme and men seemed to have hardly a toehold in the home, and these young girls were already aware of this.

They were cheap labour and at the age of sixteen they would often be unemployed, like their elder sisters, but in the meantime they were frequently the most affluent members of their household, with money to spend in Woolworth’s on cosmetics and rhinestone jewellery. I envied them their neat, black, work dresses and, even more, their best Sunday coats and hats and high-heeled shoes. They never spoke to me, except sometimes to jeer at my rags. At such times my glasses would mist over with tears, and I would whisk Avril and the Chariot round a corner, before the children could realize what was happening.

The local boys bullied both Avril and me, just as they did a subnormal boy who lived in the next street and a little Negress, the daughter of a medical student, who lived round the corner. None of us was human by the standards of these lads – we looked different – and we ranked with dogs and cats, to be teased and mishandled if caught.

Our family received no letters. It was as if everybody we had known before that first day in Liverpool had dropped dead. My parents always hoped for letters in reply to the endless applications for work which they wrote, but nothing arrived. Occasionally, my mother would write to an old acquaintance to beg for financial help in our predicament; there was no response.

I longed passionately to go to school, to have some small communion with a more ordered world where I might find some spark of hope of a better life through learning. I continued to pray that, since my brothers and sisters attended a Church school, the priest would one day call upon us and would discover my existence; I was sure he could make my parents send me to his school. But the Church knew us not, and I was thrown back upon my library books and what I could remember from the past.

Unlike many children, I had always enjoyed going to church. The major festivals of the year were to me wonderful theatrical productions, and my introduction to the works of many great composers had been through hearing their music pouring forth from a well-played organ on such occasions. Some of the churches I had attended were hundreds of years old and had priceless paintings, tapestries, vestments, carvings in stone and wood, magnificent brasswork and gold ornaments, a wealth of beauty on which the myopic eyes of a small girl could feast when the sermon became boring.

The beauty of the language of King James’s Version of the Bible and of the Church of England Prayer-Book and the rich poetry of the hymn-book were not lost upon me, and enriched my knowledge of the English tongue.

Now, when mental stimulus was most required and religious comfort desperately needed, these things were gone from us. I believed that God was not just angry with us – he was simply furious.

Apart from being exposed to the scholarship and intellectual wealth of the Church of England, I was fortunate in having well-educated parents. They were extremely modern in their day and surrounded themselves with friends who discussed at length ideas and concepts of the times as well as more mundane matters.

As the eldest child, I was sometimes allowed to leave the nursery and sit with my elders in the drawing-room. Bearing in mind the hissed instructions of Nanny to ‘hold my hush’, I would sit, like a sleepy owl, on a stool by the white marble fireplace, admiring Mother’s collection of Georgian silver which winked at me in the firelight from an antique sideboard.

The drawing-room always seemed to be full of well-tailored gentlemen, some of them economists and bankers, others wealthy merchants; and a younger group clustered round my mother talking witty nonsense to her. I did not always understand what was discussed – I was too young. I soon became aware of the world and its problems, however, as seen through the eyes of the upper middle class. There was a place called the Stock Market inhabited by bulls and bears; and there were far-away countries, like India and China, where men made fortunes. There were terrifying food shortages called famines when men died in the streets; there were wonderful farms, full of sheep, in Australia, and others equally full of wheat in Canada. There were ships to be built, railways to sell and venturesome investments to be made in car, radio and electric-light-bulb firms.

The world was a wonderful, exciting place, and I longed to grow up and be part of it

Nobody mentioned the kind of world in which I now lived. Perhaps my father’s friends did not know of its existence, or, if they did, preferred to forget it And where were my father’s friends?

I kneeled on the floor by the window of our top-floor eyrie and looked down at the unemployed men playing one of their endless games of ollies, a form of marbles. I remembered how Joan had ignored me when I had met her. I supposed that Father’s friends had done the same.

So much for friendship.

One form of communication which was very rare in such streets as I looked down upon was telephoning. The public telephone was beginning to make its appearance; but even that assumed that the public had friends or businesses with telephones, to whom they wished to speak. In my new world, families still sent one of the family with either a written or verbal message.

Father had always been interested in French history, particularly the reign of Louis XIV, and I had been with him on a number of interesting trips to museums to see new acquisitions of jewellery, clothing or furniture of this period. It occurred to me, one day, that Avril and I could go to the museum together, so I pushed the little girl and Edward in the Chariot all the way to the city and then across it to William Brown Street. I pulled the Chariot up and down three huge flights of steps until I found the right building, and was just struggling to get the pram through a recalcitrant door when a voice boomed, ‘Where are you going with that thing?’

A very large commissionaire stood behind me.

‘I’m going to the museum,’ I replied nervously.

‘Not with that you’re not.’

His remark was clear enough, but there was a hint of puzzlement in the tone of his voice when he made it.

I looked sadly down at Avril. I was afraid to leave the Chariot outside, in case some urchin thought it was abandoned and took it to play with.

I looked up at the commissionaire and was prepared to do battle.

He must have seen the malignant gleam in my eye, because he said sharply, ‘Now you just take that thing back to where you found it, and don’t let me find you loitering round here again.’

Loitering was something one could be arrested for, I knew, so I swallowed the bitter words that came to mind, and silently turned and bounced the Chariot back down the steps so fast that I cannonaded into an elderly, distinguished-looking gentleman coming up.

‘Oh, I beg your pardon, sir,’ I said, horrified at having struck such a gentle, scholarly type of person. ‘I hope I haven’t hurt you badly.’

‘Not at all. My briefcase took the blow,’ he replied kindly, as he stared in surprise at Avril and me. His lips parted, as if to ask me something, but I had been so humiliated by the commissionaire that I felt I was going to cry, and I hastened onward across the street to St George’s Hall. Once there, I looked back.

The gentleman was standing at the door of the museum still staring curiously at me.

I giggled suddenly through my tears. An Oxford accent coming from a bundle of rags and bones like me must have really puzzled him. It had not, however, impressed the commissionaire and gained me entry to the museum.

So much for public cultural emporia.