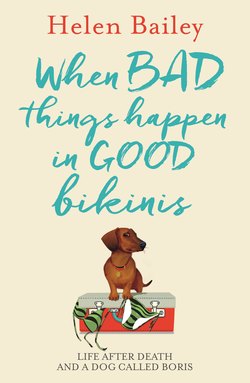

Читать книгу When Bad Things Happen in Good Bikinis - Helen Bailey - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THE TISSUE ISSUE:

COUNSELLING PART TWO

ОглавлениеDuring out of control crying episodes, as much fluid seems to escape my mouth as it does my eyes. Weird. And Messy. ~ Emma A

I was offered counselling seconds after my husband died and whilst still wearing that wretched Bikini of Death. Ushered out of the hospital side room where my husband lay – navy blue, stone-cold and dead on a trolley in his blue Burberry swimming shorts – I was approached by someone with a leaflet in their hand who asked me if I wanted counselling. ‘When?’ I asked. ‘Now,’ she said. ‘I just want to go home,’ I said. ‘Someone will run you back to the hotel,’ I was told. ‘No,’ I said. ‘I want to go home, now. I want to get on a plane and go home.’ ‘That’s not possible,’ they said. No one mentioned counselling again. I found the leaflet when I was packing up the hotel room five days later to finally go home: it was a prayer card. Looking back, it reminds me of when my friend gave birth to a whopper of a baby girl, and the midwife asked the new and still sore mother what contraception she intended to use: well meant, but terrible timing.

Back in the UK, despite my Fat Man and Beardy-Weirdy-induced distrust of therapists, including another attempt to resolve my panic attacks, this time with a woman who seemed more obsessed with picking the flaky skin off her scabby spots and examining it between her fingers than listening to me, it became clear that I was going to need professional help. You expect to come home from holiday with a tan and a bottle of the local grog, not an interim Death Certificate and an unused airline ticket.

Grief literature provided by the Foreign Office suggested I contact my GP who would be able to ‘outline the range of services in your borough’, which in my area of north London turned out to be a six-month waiting list for NHS counselling, and no immediate help from volunteer-strapped Cruse*. My only option was to go private.

The trauma psychotherapist my GP recommended came straight out of Central Casting. Small, bespectacled and grey-haired with a penchant for purple clothes and ethnic jewellery, she reminded me of the American Jewish Sex Therapist, Doctor Ruth, except my Doktor R (as Hat christened her) was from north London rather than New York via Germany.

Each session with Doktor R followed the same pattern. Twice a week, we’d face each other in wing-backed chairs as with a sad smile she’d enquire, ‘How has it been?’ my cue to sob and snot not just for England and St George, but for widows everywhere. After forty-five minutes, Doktor R would leave the room to ‘think’, whilst I sat in her fire-hazard of a study doing my own thinking, which was usually along the lines of wondering whether she was an obsessive compulsive hoarder which stopped her throwing anything out. Then she’d return to trot out such gems as, ‘You’re coping remarkably well,’ or, ‘I am impressed by your resilience,’ after which I would hand her cash, book another appointment and drive to the nearest Rymans to buy box files and envelopes in an attempt to deal with the mounting pile of ‘deadmin’: paperwork relating to JS’s death and its aftermath.

At first it was a relief to sit and sob with a professional who I assumed would try and pull me back if I became suicidal and ran out into the traffic, something I had done several times as part of my death wish. She also gave me one very good piece of advice: ‘Never underestimate the healing power of the mundane,’ something that saw me furiously hosing out the stinky wheelie bin in the hope of snaffling extra healing points.

But after a few sessions, it all went horribly wrong.

Doktor R kept a box of tissues strategically placed to my right. During each session I went through these like a dose of salts, something not helped by the fact they were of the scratchy, thin, ‘budget’ variety. One sob-and-snot-wipe combo and they dissolved into damp shreds, leaving my nose sore and raw. About to leave the house for another Doktor R sobfest, I grabbed a bunch of my own tissues – Kleenex Ultra man-sized with a touch of balm – and bunged them in my bag.

I sit in front of Doktor R and before she can give me her regulation, ‘How has it been?’ intro, I pull out the wad of quality tissues, wave them in the air and announce that I have brought my own supplies.

45 minutes of sobbing later, Doktor R gives me her analysis of the session.

‘I see you have brought your own tissues,’ she smiles.

‘Um, yes,’ I say.

‘I’m wondering if this is your attempt to take some control over your own grief?’ she ponders.

This is barmy. I tell her it is nothing to do with trying to control my own grief, just that her tissues are thin and scratchy and exfoliate my nose, whereas mine are man-sized with a hint of comforting balm.

Doktor R appears not to agree with my simple, practical explanation.

I point out that surely other clients bring their own tissues?

She cocks her head, first left, then right and tells me that some do and some don’t but – she straightens her gaze – she feels it’s significant that I am the only one to have ANNOUNCED that I have brought my own tissues.

I become wickedly obsessed with paper products to take to my next session. If I whip out toilet roll, will this signify that I don’t value myself? What if it’s quilted, premium bog roll? Coloured? Recycled? The shiny Izal stuff we had at school that smeared rather than absorbed? Would using kitchen roll send Doktor R into psychotherapy orbit, particularly if it had a Winnie the Pooh pattern on it? Would cartoon paper products lead her to believe that I was reverting to my childhood, rather than the real reason – they were on offer in Poundland?

It occurs to me that if I am spending more time trying to wind my therapist up than sorting my problems out, it’s time to call it a day.

So I did.

But I still needed help.

Desperately.

* Cruse Bereavement Care offers support after the death of someone close.